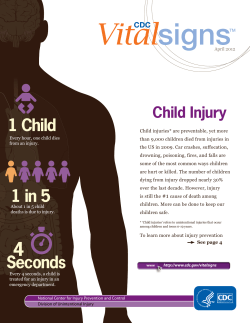

Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Departments — United States, 2001 Weekly