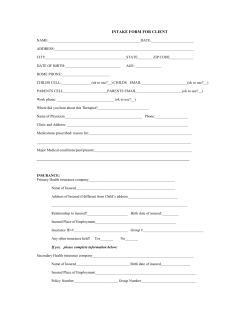

Document 140286