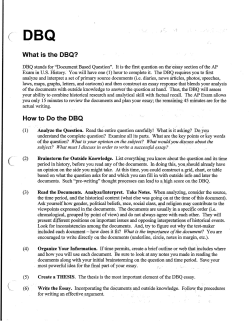

How to Study Guide 2013 Learning Services