Manual on Advance Counselling for ICTC Counsellors Participant’s Manual

Manual on Advance Counselling for

ICTC Counsellors

Participant’s Manual

Manual on Advance Counselling for ICTC Counsellors

Page 1

HIV/AIDS Knowledge and Information

This section deals with providing updated knowledge essential to working in the field of HIV/AIDS.

The following topics are included under the section:

Global/Regional/National profile

NACP-IV

Epidemiology updates

Updates on ART & PPTCT

Understanding prevalence

Understanding High Risk Groups

[For the above topics please refer to

http://naco.gov.in/NACO/Quick_Links/Publication/Annual_Report/NACO_Annual_Report/

Annual_Report_2012-13/]

Manual on Advance Counselling for ICTC Counsellors

Page 2

Use of ‘Self’ in the Counselling Process

Self awareness

Self awareness is viewed as knowledge of one’s perceptions and experiences. The cognitive

understanding that individuals have about the self, that comprises an understanding of one’s value

system and relational processes and an awareness of feelings and bodily sensations. The counselor

needs to be aware of this dynamic relationship between cognitive understanding and affective

reactions. Self awareness is a state of being conscious of one’s thoughts, feelings, beliefs, behavior,

values and attitudes and knowing how these factors are shaped by important aspects of one’s

development and social history.

Self awareness training is for the counselor to develop the ability to identify their personal

reactions and to understand and possibly utilize these reactions within the counseling relationship.

The focus on self awareness development emphasizes the role and function of the counselor’s self

in an effective counseling.

Self awareness is central to the therapeutic process in counseling. The importance of self awareness

in the therapeutic process is very important. The development of the counselor’s self awareness

must carry as much importance in his/her professional training as the assimilation of knowledge of

theories.

The counselor works closely with the client, understanding, empathizing with the client. The

counselor helps the client to understand his/her situation and problems, encouraging the client to

take decisions and supporting in behavior change. This requires that the counselor be aware of

his/her own self.

Self awareness is having a perception of one’s own personality, including their strengths,

weaknesses, thoughts, beliefs, motivation, attitudes, emotions and feelings. Self awareness allows

us to understand other persons, how they perceive us, our thoughts and our responses to them.

Self awareness is our capacity to introspect, the ability to recognize ourselves as an individual,

separate from the environment and other individuals. Self awareness means we compare the self

with standards of correctness that specify how the self needs to think, feel and behave. This is a

process of comparing the self with standards helping us to change our behavior and to experience

pride or dissatisfaction with one selves.

In the self awareness training the counselor often experience a range of emotional reactions to their

clients in the counseling process. The counselor comes across their previously held values and

views to be questioned. The counselor is encouraged to develop greater cognitive flexibility and are

required to understand how their own identities might influence the counseling process. For

example in the counseling process a counselor coming from a religious background where his/her

Manual on Advance Counselling for ICTC Counsellors

Page 3

religion prohibits consumption of liquor cannot accept alcoholism. That counselor has problem

counseling a client having an alcohol addiction. The counselor needs to be aware of his/her biases

so as to control his/her emotions in counseling that client.

To be aware of one’s own strengths and weakness helps us to be an effective counselor. The

counselor needs to be aware of one’s own values, morals, attitudes and prejudices when working in

the field of HIV counseling. Counseling in the field of HIV/AIDS means dealing with highly sensitive

and personal issues of sexuality. Sexuality requires that the counselor themselves are aware of

what is in their own mind and then they will be able to understand other’s mind.

Use of self in the counseling

process

Fostering the development of the therapeutic use of self in counseling is done by increasing the

capacities for empathy, attunement and counseling skills by the counselor. After the first activity

the counselor is now conscious of his/her values/belief, attitudes which is very important in the

field of HIV counseling, especially when the counselor is addressing various diverse sexual

practices. The counselor is aware of his/her values/beliefs and attitudes and is careful that he/she

is not biased in dealing with the client

The counselor presents themselves therapeutically to the client this requires a range of skills and

abilities including the intentional and disciplined use of the counselors self that is his/her

experience, identity, relational skills, moral awareness, knowledge and wisdom.

Viewing the counseling relationship as intended to serve as empowering role in the lives of people,

we believe that the nature of power calls for attention and understanding. The counselor

consciously uses the counselor-client relationship to bring about behavior change empowering a

CSW to negotiate the use of condom to protect themselves or their client from HIV transmission.

There are also situations in the counseling process that counselors express their own life aspects

without being aware of it. These expressions could have ill-effects and cause hindrances in the

counseling. A women counselor having a teenage daughter, in the counseling with a teenage client

becomes moralistic when hearing about the client’s sexual relationship.

The choices we make regarding the aspects of self that we bring into the particular counseling

relationship should be a function not only of what is authentic about ourselves but also crucial of

what we can offer that addresses the psychological needs of the client. For example if the counselor

is not comfortable or clear about issues in homosexuality. The counselor must be true to the client,

explore more about the issue, be open to change of personal views, control their values and learn to

deal with challenges of homosexuality. The counselor has to make an initiative to learn about

diversities in sexual orientations.

Manual on Advance Counselling for ICTC Counsellors

Page 4

Counselor’s personal growth and development

The use of “self as instrument” initiate both a respect for individual development and the meeting of

the counselor’s responsibility as a professional. When we say “self as instrument” we mean

facilitating the counselors self awareness, reflection and understanding of themselves within their

socio-cultural context and the application of this knowledge in service of their client. The

encouragement of personal growth and perspective transformation is stabilized with the

counselor’s responsibility of the self assessment and evaluation of counselor’s competence. Hence

the counselor in his/her journey of self awareness is also going to help themselves to personal

development. Looking into what are the bottle necks in the counselor’s performance and how to

deal with these bottle necks to emerge as an effective counselor.

Effective counseling training emphasizes the development of self so the counselor becomes a

competent practitioner who can feel, think and act according to each counseling situation. The

counselor’s feeling competence means the ability to relate and attune to the client using empathy

and relational connection. The counselor’s thinking competence means the ability to think critically,

conceptualize the client in theoretical terms and to demonstrate academic and research skills, oral

and writing presentations. The counselors acting competence is the professional ability to conduct

the counseling with the client.

Are you in control of yourselves?

In our life we have success and failures. These success and failures we can attribute to factors in our

control and to some factors in the environment, which are outside our control. This is called the

locus of control. Those factors that are in our control we say are “internal locus of control” for

example a counselor is not very confident in counseling as she feels she/he lacks knowledge, this is

the control of the counselor as she/he can make efforts and increase their knowledge and become

more confident. Those factors we cannot control are called “external locus of control” for example a

counselor has ailing parents who need medical attention; this is a situation that is not in our

control. Persons who develop an internal locus of control believe that they are responsible for their

own success. Those with an external locus of control believe that external forces, like luck, destiny

plays an important role in their life.

Manual on Advance Counselling for ICTC Counsellors

Page 5

Understanding Counseling Skills and

Core Competencies

Interpersonal Relationship

Skill

Greets clients

Description of the skill

The counsellor warmly and

genuinely welcomes the client

into the counselling room while

looking at him/her as opposed to

being pre occupied with filling

the registers/forms of previous

clients.

Demonstration of the particular

skill

As the client enters into the

room

Co: (verbal) Good morning! Come

in. Please have a seat.

(Non verbal) Nods head, gives

smile that the client is being

noticed

If the counsellor is preoccupied with completing the

earlier clients details, the

counsellor can tell the client

the same

Co: (verbal) Please give me five

minutes to complete a few

details from this form. After

that we can begin our

discussion.

(Non-verbal) indicates to sit by

using hands to show chair

(Please observe that counsellor is

not just giving a plain stare for the

sake of establishing eye contact as it

cannot be considered a welcoming

gesture. Also in all verbal

communication it is noteworthy to

observe the voice modulation, pitch

etc. because sometimes just saying

something doesn’t mean that it is

conveying the same thing.)

Introduces self

Counsellor tells the client his/her

name, a brief description about

Manual on Advance Counselling for ICTC Counsellors

Co: I am Sarita Sovani, appointed as

an ICTC counsellor in this centre.

Page 6

the center and its functions and

the counsellor's role in that

particular center.

Engages the client

in conversation

Listens

actively(both

verbally and non

verbally)

It implies that there should not be

awkward

silence

between

conversations which may hinder

smooth dialogue between the

counsellor and the client.

Therefore, the counsellor must be

able to use probes, open and

closed ended questions as and

when required. The counsellor

may use some light talk in

between to ease and make the

client continue the conversation

rather ending it abruptly.

The counsellor listens for total

meaning i.e. focuses both on the

content as well as the feeling or

attitude underlying the content

and responds appropriately and

sensitively to the client

This centre primarily aims to

provide

HIV/AIDS

related

counselling and testing services in

free of cost. Keeping in view the

sensitivity of the HIV testing and

related concerns all information

shared between you and me along

with the test results will be kept

completely confidential.

Co: May begin the conversation by

asking the client to talk about

themselves, for example what do

you do for a living, his/her familial

details, marital status and other non

HIV related information.

(The skill can also be demonstrated

by using appropriate verbal and non

verbal interjections like yes, ok,

hmmm, makes continuous eye

contact, nods and leans towards the

client during the conversation.)

Cl: I told my partner about my HIV

status

Co: What were you feeling when

you disclosed your HIV status

Cl: Finally I told my partner about

my HIV status

Co: I can see that you are feeling

relieved by disclosing your HIV

status

The content of both the statements

is same. However if the counsellor is

listening actively, he will recognize

the two different feeling attached to

the statements, i.e. a feeling of

anxiety in the first and the feeling of

being relief in the second and

respond accordingly.

Manual on Advance Counselling for ICTC Counsellors

Page 7

Is supportive and

Non judgmental

The counsellor frequently asks

clients about their feelings and

thoughts.

The counsellor reflects these

feelings back to the client so that

the client knows that s/he is

being understood.

The counsellor is patient and

does not try to get a word in

when the client is talking.

(The counsellor is aware that not all

communication is verbal and that a

client’s words alone don’t tell us

everything

he/she

is

communicating. For e.g. The way in

which a client hesitates in his

speech can tell us much about

his/her feelings so, too, can the

variation of his/her voice. S/He may

stress certain points loudly and

clearly and may mumble others. The

counsellor should also note such

things as the person’s facial

expressions, body posture, hand

movements, eye movements, and

breathing. All of these help to

convey the client’s total message.)

Co: Now that you have decided that

you want to take the test, how are

you feeling or what are your current

thoughts?

Co: It seems that you feel anxious

about your test result, because you

do now know what is the result.

Co: You are not alone in this. This is

a center where persons test

themselves for HIV and I work with

a lot of persons who are HIV+.

The counsellor does not become

“the expert” and offers premature Co: I am glad you trusted me with

advice.

this information. I understand it can

be difficult discussing you HIV

status and other intimate details

with me.

Cl: I also want to tell you that I am

physically intimate with my wife’s

best friend and she doesn’t know

about it.

Co: hmm….I understand your

situation. Let’s try to find out some

Manual on Advance Counselling for ICTC Counsellors

Page 8

way so that your sexual partners do

not get infected.

The counsellor does not pass any

judgment (whether critical or

favorable).

Gathering Information

Skill

Uses appropriate

balance of open

and closed

questions

Description of the skill

The counsellor does not use

close ended questions in quick

succession, as the client may

feel like s/he is being

interrogated and will become

defensive.

The counsellor

intersperses

open ended questions with a

few closed ended questions to

allow the counsellor to decide

in what direction they want to

take the conversation

The counsellor uses adequate

close ended questions to collect

facts pertaining to the client’s

problem as well as the basic

details like the clients name,

age, and marital status, where

s/he resides and information

about his family members close

ended questions.

As the session progresses, the

counsellor begins to use more

open ended questions. These

questions seek out client’s

thoughts,

emotions,

and

Manual on Advance Counselling for ICTC Counsellors

Demonstration of the particular skill

Open-ended questions:

An open-ended

question

requires more than a oneword answer, e.g.

‘What difficulties do you

experience in practising safe

sex?’

‘How do you think you would

react if you received an HIVpositive test result?’

‘When do you think would be

the right time to disclose your

test result to your spouse?’

These cannot be answered by a

simple ‘Yes’ or ‘No’

These questions invite the

client to continue talking and

allow the counsellor to decide

in what direction they want to

take the conversation.

Closed Questions:

• A closed question limits the

response of the client to oneword answers, e.g.

‘Do you practice safe sex?’

‘Do you know how to use a

condom?’

• Closed questions do not give

the opportunity to a client to

think about what they are

Page 9

experiences and invite

client to continue talking.

Uses silence well

to allow for self

expression

the

saying

• Answers to such questions can

be very brief, hence noninformative.

This

often

necessitates

further

questioning.

• However please note that

closed ended questions are not

bad and they will have to be

used in certain situations,

• e.g.

Are you willing to take ART

medicines?

Does your spouse know about

your HIV status?

In the course of counseling,

counsellor is supposed to show

patience until the client is able

to provide additional input and

responds

further.

It

is

important for the counsellor to

allow the client to gather

thoughts

and

regain

composure.

The counsellor either pauses or keeps

quiet for a few minutes, after asking

the client certain questions that

require the client to share their

personal experiences, feelings or

thoughts.

The counsellor uses statements like

“You can take your time” and “I

understand you need some time to

think about this, before you answer

this question”

During this time, the counsellor

appears patient and makes eye

contact with the client. The counsellor

does not fidget or appear

uncomfortable.

The counsellor does not allow for the

silence to continue for very long.

Seeks clarification

about information

given by the client.

The counsellor asks the client

questions about the

information shared by the

client.

Questions to seek clarification

are often worded differently

Manual on Advance Counselling for ICTC Counsellors

Cl: I used condom but, I think it did

not work.

Co: Ok. Can you please elaborate more

on “it did not work………….” as I did

not get what you mean by it.

Page 10

Avoids premature

conclusions

Summarizes main

issues discussed

than the opening question

asked by the counsellor

Drawing appropriate and right

conclusion is important for the

counsellor failing which the

client may feel that the

counsellor

is

in-attentive,

biased and/or is judgmental

about

the

client.

To

demonstrate

the

skill

counsellor does not make a

conclusion based on incomplete

information and to use this skill

the counsellor listens actively to

all that the client has to share

without interrupting the client.

In summarizaing main issue,

the counsellor is doing a

paraphrasing at the end of the

session or wherever the

counsellor feels that during the

session

the

client

have

presented facts and important

Manual on Advance Counselling for ICTC Counsellors

Drawing Premature conclusion:

Cl: Last night I went out with a few

friends and we got drunk

Co: So you visited a sex worker and

you had unprotected sex because you

were drunk.

Leading to accurate conclusion:

Cl: Last night I went out with a few

friends and we got drunk

Co: ok, so what is bothering you right

now about that event?

Cl: nothing much, we just freaked out

and wanted to have some fun.

Co: so what type of fun you had?

Cl: we tried a new drug in the market

Co: hmm …….so how did you feel

about it?

Cl: we were at the top but now I feel

guilty that I will become an drug

addict even if I have done it only once

Co: I can understand your feelings but

before we discuss more on it can you

tell me did you injected it and shared

the needle within the group or you

inhaled it?

Cl: no! No! We inhaled it through

smoking pipe.

Co: ok, so I can say that you are

feeling guilty about the act you did

last night and you are apprehensive

about being

a regular drug

inhaler…………………….

Cl: yes, that is right…………

Client : “Yes , how should I tell her I

am positive , I want to tell her because

I don’t want to infect her , and I have

to tell her because I cannot suddenly

start using condoms , but not now ,

she will get upset, I don’t know …”

Page 11

information woven in between

the underlying emotions and

works spoken and explicit

gestures. The sequence of

presentation also does not

progress as priority wise.

Amidst observing all the above

by “keeping eyes and ear open”

to make sense out of it and filter

the relevant information or

feeling is not easy for a

counsellor.

There

is

a

possibility of confusion and

being buzzed up with the

information

coming

all

together. Therefore, it is

important for counsellor to put

tighter key points of the

discussion in a few words.

Makes

proper The

counsellor

maintains

records

of descriptive

records

that

problem

explicate a client’s key issues,

formulation

for their feelings associated with

future reference

them and action points for the

future (if discussed).

Counsellor: “So can we summarise it

in this way. …“If you do not tell your

status, you fear infecting your wife.

On the other hand, you are finding it

hard to tell her as she may leave you.

Therefore, even though you want to

tell, it is very tough for you.”

(Please make sure that the summary

you provided to the client is checked

back with the client as presented

accurately or needs to be reframed).

Giving Information

Skill

Description of the skill

Gives information The counsellor uses the

in clear and simple language of the state to provide

terms

HIV related information to the

client.

The counsellor provides the

information in an appropriate

order and organized manner.

(for example information about

ART should be given only after

the client has understood the

Manual on Advance Counselling for ICTC Counsellors

Demonstration of the particular skill

Co: (in complicated terms) ELISA test

will be performed on you in the

adjacent lab to diagnose your serostatus. In case your test result is seropositive it means you have retro-virus

in your body which is cause of

acquired

immuno

deficiency

syndrome in human beings and once

you are tested sero-positive you have

potential of horizontal and vertical

transmission to others.

Page 12

modes of transmission as well

as facts about how the HIV (in simple and clear term) your blood

virus affects the immune will be tested for HIV in the lab

system)

situated opposite to the x-ray

department on the first floor. You will

be required to collect your report

result from me in the afternoon. I

would like to tell you that the if the

result is positive it means the HIV

virus is inside your body and if it is

negative it means you do not have

virus in your body. In case you have

positive result it doesn’t mean that

you have AIDS it is a condition which

develops after many years after the

virus has entered your body. You can

transmit the HIV only through the

following mediums………………….

Gives client time to The

counsellor

paces Co: Your test result is negative which

absorb

himself/herself while providing means that the virus is not inside your

information and to HIV related information.

body………………(silence)

respond

Cl: oh my God! I am so happy. I dint

S/he waits for a few minutes have sleep for the entire night.

after the providing the client Co: hmm, I can see that you are feeling

with necessary information.

quite relieved…

Cl: yes, I am very happy. I just want to

The counsellor is patient and go home and sleep

waits for the client to respond Co: you can ask me in case you are not

to the information provided

clear about anything….as you know

we have talked safe sex,.

The counsellor asks the client if Cl: yes, now I know the practices

s/he have any doubts or which I earlier used to consider safe

questions

about

the such as anal sex.

information provided to them.

Co: hmm….good…would you like to

once again summarise the safe

practices?

Has to up-to-date

knowledge about

HIV

The counsellor is aware of the

recent developments, treatment

regimes and research for their

own knowledge and in case the

client asks them. It is important

for a counsellor to be aware of

the current NACO guidelines for

treatment, care and support

Manual on Advance Counselling for ICTC Counsellors

Such as earlier the minimum CD4

count for initiating ART was 250 the

limit is recently being revised by

NACO……

Page 13

Repeats and

reinforces

important

information

The

counsellor

repeats

important

parts

of

the

information given to the client.

Repeating information should

not reflect that counsellor is

parroting the given information

rather it is for bringing more

clarity on the information

shared and in case counsellor

has listened incorrectly it can

be reprimanded then and there

only. The counsellor may add

additional information to help

the client gain an improved

understanding of the facts

provided.

Illustration1:

Cl: I wanted to get rid of all my

miseries…you know life is just

miserable if my wife will leave me. I

thought I should either tell her or end

it.

Co: hmm…either ends it??????

Cl: yes, end this relationship without

telling her the truth

Co: hmm…I can understand how

difficult it is for you….

Illustration 2:

Cl: Now I know there are three modes

of transmission, they are through

unsafe sexual intercourse, blood

For

example,

modes

of transfusion and from mother to her

transmission, the meaning of unborn child

CD 4, information about ART, Co: yes you are right, mother to her

etc.

unborn but it may also be transmitted

from mother to her new born child

through breast feeding.

Cl: ohh! I din’t know it

Checks for

It is important to check

understanding and whether “what is being said is

misunderstanding understood correctly by the

client and/or the counsellor?”

in order to minimize confusion

and ambiguity.

Summarizes main

issues

(The counsellor may

also use

relevant examples that help the client

gain a comprehensive understanding

of the information provided )

“Can you please tell me, what you

have understood from the

information I have just provided you?

(The counsellor may use open ended

questions or just repeat the important

information to gauge if the client has

.

understood the information given to

him or her. Based on the response

given by the client to the above

questions, the counsellor checks for

any misunderstanding. If any are

present, the counsellor clarifies the

same)

In summarizing main issues, the Cl: “I love my wife, but she will get

counsellor

is

doing

a very angry with me if she comes to

Manual on Advance Counselling for ICTC Counsellors

Page 14

paraphrasing at the end of the

session or wherever the

counsellor feels that during the

session

the

client

have

presented facts and important

information woven in between

the underlying emotions and

words spoken and explicit

gestures. The sequence of

presentation also does not

progress as priority wise.

Amidst observing all the above

by “keeping eyes and ear open”

to make sense out of it and filter

the relevant information or

feeling is not easy for a

counsellor.

There

is

a

possibility of confusion and

being buzzed up with the

information coming all tighter.

Therefore, it is important for

counsellor to put together key

points of the discussion in a few

words.

know that I am HIV positive, she will

hate me and leave me.”

Co: So can we summarise it in this

way. …“If you do not tell your status,

you fear infecting your wife. On the

other hand, you are finding it hard to

tell her as she may leave you.

Therefore, even though you want to

tell, it is very tough for you.”

“Please make sure that the summary

you provided to the client is checked

back with the client as presented

accurately or needs to be reframed.”

Handling Special Circumstances

Skill

Description of the skill

Demonstration of the particular skill

Talks about

sensitive issues

plainly and

appropriately to

the culture

When talking about sensitive

issues for example sexual

history or sexuality related

issues, the counsellor is

straightforward. For example

the counsellor makes his/her

intention clear at the beginning

of the discussion itself. An

example is given alongside.

“We will now discuss certain personal

details like condom use and your last

sexual encounter. I understand that

you may feel uncomfortable in

discussing it at first. However I need

to know this information, so that we

can proceed with the appropriate

course of action for your HIV testing

and treatment”

(The counsellor has the appropriate

The counsellor uses clear and knowledge of and is aware of the

Manual on Advance Counselling for ICTC Counsellors

Page 15

instantly recognizable language

in the discussion of sensitive

topics like safe sex or disclosure

related issues.

Prioritizes issues

to cope with

limited time in

short contacts

Keeping in mind the limited

time available for a counselling

session, the counsellor is able to

identify issues which are most

distressing to the client.

From amongst these issues, the

counsellor is able to identify

issues that fall within the

purview of counselling as

compared to issues that are

beyond counselling like poverty

alleviation

or

livelihood

options.

Uses silences well

to deal with

difficult emotions

The counsellor either pauses or

keeps quiet for a few minutes

when the client is expressing

emotions like excessive grief,

anger,

sorrow

or

even

Manual on Advance Counselling for ICTC Counsellors

client’s background details like

gender/class/caste/sexuality/age/fin

ancial status/marital status and

current cultural norms. While dealing

with sensitive topics, the counsellor

frames his/her statements based on

the same.)

Cl: I feel that my children will be

discriminated if they are tested

positive like us. I want to relocate

from this place because we have very

close

relationships

with

our

neighbors and they will come to know

that something is wrong with us.

Though they are supportive and will

not discriminate but do not want to

tell them.

Co: You have discussed two, three

important issues here. It seems there

is a lot going on in your mind. Taking

up the issues altogether will make the

situation complex and difficult to

handle. Therefore, what you can do is

note down all the issues which are

cause of your concern and arrange

them in ascending order depending

on the issues which needs immediate

action, which may be put on hold for

some time and which may be resolved

later on when situation is under

control…..

I can help you in identifying some

issues which you may put in order as

explained above such as your children

will be discriminated if they come

positive, secondly, you are concerned

about neighbors, thirdly you also feel

that they are close to you and are

supportive.

Co: “I have some bad news for you;

your test report is HIV positive”

Cl: “What”?? (Breaks down into tears

…)

Co: “It is ok, I understand you need

Page 16

happiness.

The counsellor uses silence

after the client has finished

expressing difficult emotions to

allow the client time to reflect

on what they have shared.

some

time

to

absorb

this

information…………”

(and

stops

talking for a few seconds )

Client: “I am sorry” (again breaks

down into tears …)

Counsellor: “You can take your

time……………”,

Manages client’s

distress

The counsellor pays attention

and

acknowledges

the

disturbing

thoughts

and

feelings of the client such as

feelings

of

loneliness,

hopelessness, anxiety, guilt,

helplessness etc. The counsellor

needs to address such concerns

and behavior of the client soon

after they are observed.

The counsellor emphasizes

upon the duration and intensity

of such feelings in order to

assess the need for any further

mental

health

related

intervention.

Co: Can you explain that how are

feeling right now, I can see that you

are sweating a lot… should I increase

the speed of fan…..have some water

first and tell me in detail….I am there

for you…you can hold my hand if you

wish so.

Handles client’s

defensiveness

sensitively and

well

It is possible for a client to be

defensive about her/his actions,

behavior and the information

and knowledge shared. It is

important that the counsellor is

patient and empathetic when

the client is trying to justify

his/her actions or is denying

certain emotions they may be

feeling.

Cl: I cannot take all ART medicines in

time. I have lots of other work to do.

Co: I understand it is not possible for

you to remember all the medicines

and you have quite busy schedule. But

as it is very important for your health

not to skip then….. Together we will

find out some way that it becomes

easy for you.

(When the client is being defensive

the counsellor does not attempt to

correct the client or tell the client that

he/she is wrong or lying.)

Manual on Advance Counselling for ICTC Counsellors

Page 17

Counselling Skills

Skill

Description of the skill

Demonstration of the particular skill

Active

listening

The counsellor listens for

total meaning i.e. focuses

both on the content and

the feeling or attitude

underlying the content and

responds

appropriately

and sensitively to the client

The counsellor is aware that not all

communication is verbal and that a client’s

words alone don’t tell us everything he/she is

communicating.

For eg. The way in which a client hesitates in

his speech can tell us much about his/her

feelings. So, too, can the variation of his/her

voice.

S/He may stress certain points loudly and

clearly and

may mumble others. The counsellor should also

note such things as the person’s facial

expressions, body posture, hand movements,

eye movements, and breathing. All of these help

to convey the client’s total message.

Paraphrasing

The counsellor restates or

repeats the client’s words

in a shortened and clarified

form. While doing so, the

counsellor ensures that

his/her words are in

congruence

with

the

client’s verbal and non

verbal language.

Cl: “I love my wife, but she will get very angry

with me if she comes to know that I am HIV

positive, she will hate me and leave me.”

Co: “What you are saying is that your wife will

be upset with you and you feel that after

knowing your status, her love for you will

become less and she may want to discontinue

the marriage”

Reflecting

Also the counsellor can

use some of his/her own

words to convey the real

meaning of what the client

is saying as well as feeling

and experiencing.

The counsellor is accurate

in

recognizing

the

emotions that lie beneath

the client’s verbal and non

verbal communication.

The counsellor reflects

Co: It sounds like you are worried about your

wife’s HIV status.

From what you have shared, it seems you may

be feeling anxious about your health.

Manual on Advance Counselling for ICTC Counsellors

Page 18

Confronting

Empathizing

back to the client with the

use of a different set of

words, the emotions that

the client seems to be

feeling.

The counsellor is able to "On the one hand you say you are not anxious

accurately identify mixed about the HIV test results but on the other

messages, discrepancies, hand, your behavior indicates otherwise”

and incongruities between

the content of what the

client is saying and his or

her non verbals, between

contradictory content and

between behaviors and

stated goals.

The counsellor points out

these discrepancies to the

client in a sensitive and

respectful manner

The counsellor is able to “I can feel that how hopeless you are feeling at

keep self in the client’s this moment because nobody is there to share

situation and feel the way your apprehensions.”

client is feeling.

The counsellor is able to

communicate empathy to

the client through both the

verbal and non-verbal

communication

Goal Setting

The counselor is able to

identify accurately assess

the client's problem(s) and

then assist him or her in

finding the workable and

realistic

option

or

solution(s).

Cl: I do not know how I can improve my health.

I am ignoring it constantly. There is no one to

take care of my routine. My husband comes

home late as he works hard. I do not want to

burden him to look after my ART medicine

schedule. I am also falling ill often. But I have no

choice, I think like is soon going to over. I am

worried who will take care of my husband after

The counsellor is able to me as he is very much attached to me.

assist the client in listing

goals that be specific, Co: if I am not mistaken, it is clear from the

measurable,

realistic, issues you discussed that you want to be with

psychologically

and your husband for many more years but you fear

emotionally healthful, and that you will die leaving him alone.

Manual on Advance Counselling for ICTC Counsellors

Page 19

arranged in their order of

importance.

Cl: Yes, you are right. I want to live healthy

Co: So let’s set a goal you want to achieve and

sub goals to achieve the main goal. Please set

such goals that can be achieved with the

available resources, services and support

Cl: hmm……ok.

Main goal: Living healthy life with my husband.

Sub-goals 1: Taking care of my health

2: adhering to ART

Co: Good, now write down the ways how you

can achieve it

Cl: ok, I can go to a dietician for diet chart. I can

put reminders for ART medicines based on the

T.V. shows timings.

Co: Yes, good, that will be great…now set

timeline for each goal that you…………………..

Facilitating

The counsellor is able to

smoothen

the

client’s

sharing

of

feelings,

ventilation of emotions,

discussing the concerned

issue, choosing among

workable options and goal

setting to achieve the set

goal

The counsellor is able to

ease and speed up the

intake of other related

services such as linking to

positive network, availing

other welfare services,

getting legal and ethical

help etc.

Unconditional Counsellor is able to give

positive

respect to the client

regard

irrespective of the gender,

sexual orientation, caste,

class, profession and creed

Co: I am giving you this referral slip, show it to

the PLHIV network head, I have already called

him up for the same.

You can cry, if you are feeling like….do not

press your emotions, just let them go.

“ offering seat to a female sex worker client like

other clients”

“Giving information to the illiterate clients in

simple language rather considering them

incapable of understanding anything.”

Manual on Advance Counselling for ICTC Counsellors

Page 20

of the client

Cl: though my wife is taking care of me and

loves me a lot still I want to divorce her because

the relationship is not sexually satisfying to me.

She hardly feels any need for physical intimacy

and is reluctant even if I pursue it.

Co: As we already have talked about it in detail

and based on all pros and cons of breaking up

this relationship you have arrived on this

conclusion. You have also taken up with your

wife, it is good that both of you have mutually

agreed for it. Therefore, I wish best to you for a

prosperous life ahead.

Summarizing

In summarizing main issue,

the counsellor is doing a

paraphrasing at the end of

the session or wherever

the counsellor feels that

during the session the

client have presented facts

and important information

woven in between the

underlying emotions and

words spoken and explicit

gestures. The sequence of

presentation also does not

progress as priority wise.

Amidst observing all the

above by “keeping eyes

and ear open” to make

sense out of it and filter the

relevant information or

feeling is not easy for a

counsellor. There is a

possibility of confusion and

being buzzed up with the

information coming all

together. Therefore, it is

important for counsellor to

put together key points of

the discussion in a few

Cl: “I love my wife, but she will get very angry

with me if she comes to know that I am HIV

positive, she will hate me and leave me.”

Co: So can we summarise it in this way. …“If you

do not tell your status, you fear infecting your

wife. On the other hand, you are finding it hard

to tell her as she may leave you. Therefore, even

though you want to tell, it is very tough for

you.”

“Please make sure that the summary you

provided to the client is checked back with the

client as presented accurately or needs t be

reframed.”

Manual on Advance Counselling for ICTC Counsellors

Page 21

words.

Disclosure

skills

The counsellor is able to

tell the client any sensitive

and/or

important

information which may

bring

apprehensions,

anxiety or distress in the

client in a non-threatening,

clear and correct way

personal to the client and

with

the

client’s

permission

to

the

significant others who are

related to the client

directly or indirectly.

Co: Your husband has brought you here

because he wants to share something important

with you. It is difficult for him to speak to you

about it so he wants me to share it with you.

Please be assured that whatever he has shared

with me is between us only and is not being

disclosed to anyone. It is important for you to

know it as it may affect you directly or

indirectly…….

One of the techniques that can be used is the

Sandwich Technique: It follows the physical

layout of a sandwich – two slices of bread with

a filling.

Upper slice of bread:

“I have some bad news to give you. You may or

may not be expecting this.” Announcing that the

news is bad gives the parent a few seconds to

prepare themselves to actually hear the words

which are going to dash their hopes.

Sandwich filling:

“The child’s test result is positive.” This is the

actual news of the test result.

Lower slice of bread:

“I am here to help you absorb this shock.” This

is the offer of support from the counsellor. Just

as the bread supports the filling, so the

counsellor offers support for digesting the bad

news.

Manual on Advance Counselling for ICTC Counsellors

Page 22

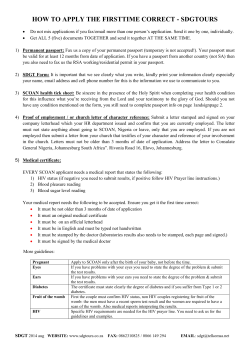

Strengthening Service Linkages

Programmatic Linkages for the ICTC

Each ICTC must establish the following programmatic linkages with other health services.

Some of these services fall under the NACP umbrella. Some are within the general health

system. The performance of the ICTC in this area is visible in completed and accurate linelists, and good entries into the columns for in-referrals and out-referrals. The counsellor

must also be aware of the services available at each of these units and guide clients

appropriately.

Care Support

&Treatment

Treatment

for Sexually

Transmitted

Infections

Maternal

&Child

Health

ICTC

Positive

People’s

network

RNTCP

Targeted

Intervention

Projects

Manual on Advance Counselling for ICTC Counsellors

Page 23

Care and Support Services :

Care and support services are available through ART centres, Link ART centres, Centres of

Excellence and Community Care Centres. However, the primary linkage between the ICTC

and the Care and Support services will be through the ART centre whose functions are:

Prevention of Opportunistic Infections

Assessment and management of HIV-related illnesses

Assessment and management of other recurrent and chronic infections

Anti-retroviral therapy

Management of other recurrent and chronic infections

Counselling for drug adherence, nutrition, infant feeding

Early Infant Diagnosis and care of the child

STI Services:

STI clinics are branded as Suraksha Clinics. They offer the following services:

Screening for presence of STI signs and symptoms

Early diagnosis and treatment of STIs during pregnancy including routine syphilis

testing of pregnant women

Syndromic diagnosis and treatment where laboratory tests are not possible

RNTCP :

Manual on Advance Counselling for ICTC Counsellors

Page 24

Under the RNTCP, there are several facilities. They offer the following services:

Screening for TB

Early diagnosis & initiation of Anti-TB Treatment

Cotrimoxazole prophylactic treatment (CPT)

Maternal and Child Health:

Linkages with Maternal and Child Health services are not just for those counsellors who are

attached to Antenatal or Gynaecology units in the hospital. Every counsellor should know

their services and how to link to them effectively:

Essential antenatal care

Family planning services

Safer delivery practices

Counselling and support for the infant feeding method opted by the woman

Maternal Care: MCH postpartum care services help protect the mother‘s health by

providing medical and psychosocial supportive care

Infant care: MCH postnatal care services offer assessment of infant growth and

development, nutritional support, immunizations, and early HIV testing.

Family care: MCH services provide social support, testing and counselling for family

members; referrals to community-based support programmes; and assistance in

dealing with stigma

Positive People’s Network:

Positive people’s networks offer Psycho-social support

Support groups

Legal support

Socio-economic support

Manual on Advance Counselling for ICTC Counsellors

Page 25

Nutritional support

Targetted Intervention (TI) Projects:

TI Projects provide:

Behaviour change communication

Referral for HIV testing

STI education and management

Condom promotion

Community mobilization

Enabling environment

Reference:- Refresher Training Programme for ICTC counsellors ( Second

edition)Trainee’s Handouts, April 2011

Manual on Advance Counselling for ICTC Counsellors

Page 26

Strengthening Service Linkages

Assistance Schemes for PLHIVs

As an ICTC counsellor, you may not always find it possible to address all the needs of your

clients within the health system. The Care and Support Programme has made provisions

for free treatment. But PLHIVs have other needs as well. Besides failing health, they face

two problems: First, their health problems often disrupt their employment leading to

breakdown in family finances. Second, they are often marginalized due to the stigma

associated with HIV/AIDS. Hence there is a need to develop linkages with other

government departments, non-HIV NGOs and the public sectors.

Types of Schemes:

HIV/AIDS affects people of all walks of life. But its impact is greatest on members of the

lower socio-economic classes. With HIV, the demand for living a healthier life is more

important than ever and the additional economic burden is the biggest barrier to accessing

the free care and support services.

There are various government schemes which a PLHIV can avail. These schemes differ

from state to state and sometimes from district to district. The information for such

schemes is available at the office of the District Collector/ District Magistrate. A partial list

is provided here. But counsellors can request this information from the office of the District

Collector or the District Magistrate or their State AIDS Control Society.

A) Social Security Schemes:

Manual on Advance Counselling for ICTC Counsellors

Page 27

Examples of such schemes are:

Widow pension scheme

Special pension schemes for PLHIVs

Old age pension scheme

Insurance schemes (government as well as private such as Star Insurance)

Employment guarantee schemes

B) Free Transport to PLHIVs for Commuting

to ART Centres :

Concessions are sometimes provided for travelling to treatment centres by state transport

agencies or by the railway authorities. However in some places, this facility has been made

available even with private transporters.

C) Below Poverty Level

Status for PLHIVs:

Inclusion of PLHIVs in the BPL list, if eligible, helps PLHIVs to get nutritional support

through subsidized rations and livelihood support through benefits under rural

development and employment schemes. It also seeks to address stigma by encouraging

disclosure of status.

D) Nutritional Support for PLHIVs :

Some states have provided nutritional support to PLHIVs through the ICDS scheme or

Antyodaya scheme or through private donors. Chandigarh SACS has in fact developed a

pooled fund through private donations like Rotary Club for providing such support. Orissa

SACS has a nutrition supplement programme.

E) Safe Environment :

Manual on Advance Counselling for ICTC Counsellors

Page 28

Some states have provisions for orphanages for CLHIVs and short-stay homes for women

affected with HIV.

F) Some states have made provisions for other schemes like animal loans, train passes,

educational loan/grant, etc.

Role of the Counsellor :

Referral

Managing Barriers

Enhancing Linkages

Referral:

An effective ICTC counsellor will gather information on the locally available schemes and

seek to link people to the right resource. PLHIV networks generally are of great help in

ensuring that these schemes are made available. Hence they would be your first referral

link for all these activities. Various TI NGOs, Link Worker Scheme (LWS) NGOs and other

non-HIV NGOs are also of great help in providing these services. You should add them to

your list of referral agencies.

The ICTC counselor should ensure that the following details are displayed prominently in

the ICTC:

List of various government schemes for PLHIVs

Name and contact details of various HIV and non-HIV NGOs providing services for

PLHIVs (Services available at each NGO should be clearly written)

A line indicating that they can ask you for more details

Managing Barriers:

Manual on Advance Counselling for ICTC Counsellors

Page 29

As a counsellor, you should be aware of the barriers that a PLHIV can face while trying to

avail a package of services. Based on experience you should explore solutions to these

barriers on a case-to case basis. Hence it is extremely important to obtain feedback from

clients for whom you have already made referrals. Providing information that is as accurate

as possible is critical. For instance, tell them how to reach there, draw a small map, etc.

Further, prepare your clients as to what to expect when they go to a particular office to

register for the scheme/ service. This is the skill of anticipatory guidance. If clients feel

uncomfortable with language or with speaking with someone more educated than them,

encourage them to talk with the District Level Network for a “buddy” who can accompany

them the first time. Other possible advocates are workers from the Link Worker Scheme.

Be sensitive to clients’ concern about being “outed” – that is having their status disclosed.

Remember it takes time for people to feel comfortable. Therefore, work with them at their

pace. But always present to them the need to get registered for treatment as soon as

possible as this is a lifesaving measure.

Prepare your clients as to what to expect when they go to a particular office to

register for the scheme/ service. This is the skill of anticipatory guidance.

Enhancing Linakges :

Developing linkages with the various government departments is extremely important for

the benefit of your client. A good rapport with your counterparts in these departments will

ensure timely and hassle-free services to your clients.

A “Thank You” note to the concerned officer will take you a long way ahead.

More Suggestions:

Manual on Advance Counselling for ICTC Counsellors

Page 30

Once you have successfully linked your client to a particular service, make a note of the

relevant details in your records for future use. Share and discuss these achievements with

your District ICTC supervisor and/or Nodal officers so that others can also benefit from

your experience. Use your records to analyse the emerging needs of your client population,

assess your success and improve your future performance

Check list for ICTC Counsellors :

Do you have the following information with you?

List of various government schemes available in the district

Name and contact address of the District Collector’s office

List of Tehsildars and their contact address

Name and address of contact persons of the District PLHIV network

Name and address of all HIV services

Name and address of the TI NGOs in the district, their area of coverage,

their typology of coverage, etc

Name and contact details of ORWs and Peer Educators in the district

and the areas covered by them in the district

Name and address of the LWS NGOs in the district

List of villages covered under the LWS in the district

Name and contact details of the link workers in the villages

Name and contact details of non-HIV NGOs in the district

Name and contact details of short stay homes for women in the district

Name and contact details of orphanages in the district

(This is a partial list that is ever-evolving)

Manual on Advance Counselling for ICTC Counsellors

Page 31

Reference:- Refresher Training Programme for ICTC counsellors ( Second

edition)Trainee’s Handouts, April 2011

Strengthening Service Linkages

Assistance Schemes at the State Level

Free Baseline Investigations:

Baseline tests are provided free of cost to PLHIVs in most of the states. This includes

tests like CBC, ESR, Urine Routine, Micro, Bl.UREA, S. CREATININE, LFT, X-Ray, USG,

Lipid Profile, HBSAg, HCV, RBS, FBS, PPBS, etc

Some states extend special services to CLHIVs. For instance, Kalawati Saran Children

Hospital in Delhi provides free diagnostic tests like CT scan and Ultra Sound for HIVpositive children.

Free Transport to PLHIV for

Commuting to ART Centres:

The states of Assam, Gujarat, Rajasthan, West Bengal, Maharashtra, Goa and

Jharkhand have provisioned travel concessions to PLHIVs for travelling to ART

centers.

In Rajasthan some private transporters are providing concessions to PLHIVs on

specific routes which cover ICTC, ART centres and TB hospitals.

Manual on Advance Counselling for ICTC Counsellors

Page 32

In Gujarat, PLHIVs are receiving reimbursement of travel expenses with financial

support from Clinton foundation and NRHM. This programme was implemented

under the Jantan Project in October 2009. The government has earmarked Rs. 1.8

Crores for this purpose in the state health budget.

In Karnataka, travel assistance is provided in two high-prevalence districts.

In the states of Kerala, Chattisgarh and Andhra Pradesh, the proposal is under

consideration with the state transport departments.

BPL Status :

Inclusion of PLHIVs in the BPL list helps them to get nutritional support through subsidized

ration, livelihood support through benefits under rural development and employment

schemes. Currently, Orissa, Rajasthan, Assam and Gujarat have given BPL status to PLHIVs.

Nutritional Support for PLHIV :

The states of Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, Delhi, Gujarat, Orissa, Haryana, Rajasthan, West

Bengal, Goa and Kerala are supporting nutritional care of PLHIVs, through ICDS,

Antyoday Anna Yojana or private donors.

In Gujarat, the Social Justice and Empowerment Department declared support of Rs.

500 per month to PLHIVs for nutritional support under Medical Aid Scheme for

lifelong.

In Kerala, the Social Welfare Department has sanctioned an amount of Rs. 49.64

Lakhs for nutrition support programme for WLHIVs and CLHIVs registered in ART

centres. Nutrimix powder (4 Kg p.m for WLHIVs, 2 Kg p.m for Pre ART and CLHIVs)

is provided through the ICDS. Besides, multi vitamin, folic acid and iron tablets are

Manual on Advance Counselling for ICTC Counsellors

Page 33

provided to children wherever required. Free nutritional kits are also provided,

through ICDS to all PLHIVs registered in DICs. This project is rolled out in 4 districts.

In Andhra Pradesh, CLHIVs in 4 districts are provided a special nutrition package

every month under the Balasahayoga Program.

Social Security Schemes:

Andhra Pradesh, Delhi, Gujarat, Orissa, Rajasthan, Tamil Nadu, West Bengal and Goa

have incorporated social security measures through widow pension, old age

pensions or special pension for PLHIV.

Orissa is providing Madhubabu pension scheme for PLHIVs and provides financial

support of Rs 400 per month.

In states where widow pensions were already being provided, the SACS have

advocated with the state governments to reduce the age bar for widows of PLHIV.

In Andhra Pradesh, PSI has launched insurance for PLHIVs through Star Health and

Allied Insurance Company.

In Rajasthan, the Department of Social Justice and Empowerment provides monthly

pension of Rs. 400 per month for all PLHIV widows.

In West Bengal, a one-time widow pension of Rs. 10,000/- is provided.

Legal Aid :

Manual on Advance Counselling for ICTC Counsellors

Page 34

The states of Chattisgarh, Punjab, West Bengal, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh have

provisions of legal aid for PLHIV through different models.

In Gujarat, an MoU regarding free legal aid to PLHIV has been signed between

GSNP+ and district legal aid authorities.

The Bar Associations of Durg, Korba (Chattisgarh), Alwar (Rajasthan), Itawah, Mau,

Devaria (Uttar Pradesh), Alipore (West Bengal) have committed and are providing

free legal aid for PLHIVs

In Punjab, free legal aid is given to PLHIVs through the District Legal Authority and

the Human Right Law Network.

In Tamil Nadu, Legal Aid Cells are set up in 16 ART centres to address various social,

legal and livelihood issues of the PLHIVs.

Safe Environment :

Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, Delhi, Gujarat, Punjab and Rajasthan have provisions for

orphanages for CLHIV as well as short stay homes for Women Living with HIV.

In Patna, Bihar, FXB India runs a short stay home for all PLHIVs.

In Gujarat, the government has planned two homes for CLHIVs in Surat and

Gandhinagar respectively. The Gujarat government is extending a financial support

of Rs. 65 lakhs per annum for this initiative.

Grievance Redressal Mechanism :

Manual on Advance Counselling for ICTC Counsellors

Page 35

The states of Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, Delhi, Gujarat, Orissa, Punjab, Rajasthan, Uttar

Pradesh, Maharashtra Jharkhand and Kerala have Grievance Redressal mechanisms in

place.

Additional Schemes:

Some SACS have worked on making additional provisions for PLHIV on the basis of their

needs.

In Rajasthan, the Palanhar Yojana is run by the Department of Social Justice and

Empowerment for CLHIVs. Rs. 500 per month is given to children upto age 5, Rs.

650 per month to school going children and an additional Rs. 2000 per year for

expenses such as uniform and study materials.

In West Bengal, Ambuja Cement Foundation supports the education of children

affected by HIV.

Jharkhand SACS has facilitated the formation of District Level Positive People’s

networks and the State Positive People’s network.

Haryana SACS has facilitated the formation of seven District Level Positive People’s

networks.

In Kerala, under the Ashraya scheme, poor families are adopted by PRIs to provide

housing, food, medical care etc as per the requirement of the beneficiary.

In Karnataka there is a special government OVC scheme in three districts worth

Rs. 1 Crore

Manual on Advance Counselling for ICTC Counsellors

Page 36

Government of Tamilnadu gives educational assistance to infected and affected

children through the OVC Trust.

Gujarat has organized educational scholarships for affected and infected children of

HIV positive parents. Another support is in the form of special (and confidential)

leave for the

children for ART and OI treatment. The government has earmarked Rs. 60 lakhs for

the parents who adopt CLHIVs.

The Union Territory of Chandigarh is planning to establish a school-cum-vocational

training centre for CLHIVs with boarding facilities.

In Chandigarh, a corpus fund has been initiated by the Union Territory of

Chandigarh with the help of donations from NGOs and philanthropic organizations.

This money is utilized to support investigations and treatment of poor PLHIVs.

Sewing and embroidery machines are provided to the DIC to develop the skills of

the PLHIVs and subsequently ensure a sustainable livelihood to them.

In Haryana, special remuneration is given to Health Care Providers (ASHAs

[Accredited Social Health Activists]) for accompanying positive pregnant women for

institutional delivery. Orissa also gives this kind of assistance to pregnant WLHIVs.

In Karnataka, under the Yashaswini scheme, incentives are given to the entire

medical team that attends to the delivery of positive pregnant women.

Reference:- Refresher Training Programme for ICTC counsellors ( Second

edition)Trainee’s Handouts, April 2011

Manual on Advance Counselling for ICTC Counsellors

Page 37

Strengthening Service Linkages

ICTC – ART Linkages

ICTCs are the first contact point of the client with the entire range of preventive, care and

support services provided under the National AIDS Control Programme. The ICTC must link

clients appropriately with the Care and Treatment services they need. However, there is a

substantial loss of clients between ICTCs and ART centres.

A study of clients followed from ICTCs to ART Centres has shown that 82.9% of clients had

received information about the availability of free ARV medications at government ART

centers and 77.5% had been given referral slips by the ICTC counsellor. This means some

clients are still not getting complete information.

The study showed that younger clients, single clients and clients working as unskilled

manual labour are less likely to register for ART. Further, ICTC clients who perceive

themselves as enjoying relatively good health or who fear disclosure of their HIV status are

also less likely to register at ART centres.

Manual on Advance Counselling for ICTC Counsellors

Page 38

Role of ICTC Counsellor in

ensuring linkage with ART:

Centre –

The ICTC counsellor should try to address these barriers during counselling and ensure

that PLHIVs reach the ART centres. One way to do this is to check in with the ART Centre at

monthly coordination meetings or over the telephone whether clients reached after a

referral has been made. You can also periodically look over the referral forms returned

from the ART centre. Matching the returned forms against the forms you wrote out will be

useful to know who reached and who did not. This is a simple way of checking. Another

way is line-listing.

ICTC counsellors may also use contact telephone numbers to contact clients who have not

reached even 6 weeks after the test. Of course, for this, counsellors should seek permission

to contact the client over the telephone and should be very discreet while making the

telephone call. Your goal as an ICTC counsellor is to ensure that each and every one of your

positive clients has reached and registered at the ART centre.

The ICTC counsellor must also give hope to the client by informing him/ her about ART, its

importance and its free availability at the ART centre. Inform the client what he/ she can

expect at the ART centre. This is called Anticipatory Guidance. Providing the client an

idea of what happens at the ART centre will make him/ her feel less anxious about what to

expect, and perhaps more tolerant of the wait-time required for the initial investigations.

Prepare your clients as to what to expect when they go to

the ART Centre. This is the skill of anticipatory guidance.

Manual on Advance Counselling for ICTC Counsellors

Page 39

Discuss with him/ her about the services available at ART centre. Inform them that at the

ART centre they will be registered into Pre-ART care by the ART counsellor. For the

registration they have to carry the ICTC test result, a documentary proof of address,

two passport-size photographs and the referral form. The ART counsellor will make the

patient ID card and will refer the client to the Medical Officer for the necessary

investigations (including the CD4 count).

The reports are usually available on the next day. Based on the reports the medical officer

will prescribe treatment. The client will also interact with the counsellor and the nurse at

the ART centre. After treatment has begun, he/she will have to follow up each month at the

ART centre to obtain the drugs as well as to have the routine monthly check.

Provide the referral form to the clients and give them accurate instructions to reach the

ART centre. It may be a good idea to display a small map on your ICTC wall.

Once the HIV-positive client is registered at the ART centre, all basic investigations are

carried out including the CD 4 count The ART centre counsellor will send the referral form

back to the ICTC by email (or by post if e-mail is not available) after filling in the necessary

details.

For registration at the ART centre, clients must carry

ICTC test result

Documentary proof of address

2 passport-size photographs

Referral form

Manual on Advance Counselling for ICTC Counsellors

Page 40

Reference:- Refresher Training Programme for ICTC counsellors ( Second

edition)Trainee’s Handouts, April 2011

Understanding Marginalization and Vulnerability in Relation to HIV

Stigma and Discrimination

Social responses of fear, denial, stigma and discrimination have accompanied the HIV epidemic

right from the time it was first discovered in India. The HIV epidemic is considered to be a three

fold, as in, an epidemic of HIV, AIDS and stigma and discrimination. Stigma and discrimination are

potentially the most difficult aspects of HIV/AIDS to address, but addressing them is key to

overcoming the spread of the disease.

Meaning of Stigma

StigmaMeaning

is associated

with disfiguring or incurable diseases, in particular, diseases that society

of Stigma

perceives to be caused by the violation of social norms, including norms about sexual behavior.

HIV/AIDS is a good example of this type of disease.

Parker (et. al., 2002) describe stigma as a tool of social control that is used to identify and use

“differences” between groups of people to create and legitimize social hierarchies and inequalities.

Stigma ‘significantly discredits’ an individual in the eyes of others and also has important

consequences for the way in which individuals come to see themselves.

Why is there Stigma in HIV and AIDS?

Meaning of Stigma

Factors which contribute to HIV/AIDS-related stigma:

Manual on Advance Counselling for ICTC Counsellors

Page 41

HIV/AIDS is a life-threatening disease.

HIV is associated with behaviours (such as sex between men, injecting drug-use, sex with women in

prostitution) that are already stigmatized in our society.

People living with HIV/AIDS are often thought of being responsible for becoming infected.

Religious or moral beliefs lead some people to believe that having HIV/AIDS is the result of moral

fault (such as promiscuity or 'deviant sex') that deserves to be punished.

Fear of contagion and death among people.

Incomplete/ incorrect information about HIV and AIDS.

In the past, diseases like leprosy, cholera and tuberculosis, the real or supposed contagiousness of

the disease led to the isolation and exclusion of infected people. In the early stages of the AIDS

epidemic, a series of powerful images (see box below), were used that reinforced and legitimized

stigmatization.

Perceptions and Images associated with HIV/ AIDS:

As punishment (e.g. for immoral behaviour)

As a crime (e.g. in relation to innocent and guilty victims)

As war (e.g. in relation to a virus which need to be fought)

As horror (e.g. in which infected people are demonized and feared)

As otherness (e.g. HIV cannot happen to me, but only to others who are set apart)

Together with the widespread belief that HIV/AIDS is shameful, the above images represent 'readymade' but inaccurate explanations that provide a powerful basis for both stigma and

discrimination. These stereotypes also enable some people to deny that they are likely to be

infected or affected.

Meaning of Discrimination

Meaning of Stigma

Discrimination occurs when a distinction is made against a person that results in his or her being

treated unfairly and unjustly on the basis of their belonging, or being perceived to belong, to a

particular group. Hospital or prison staff, for example, may deny health services to a person living

with HIV/AIDS. Or employers may terminate a worker’s employment on the grounds of his or her

actual or presumed HIV positive status. Families and communities may reject and ostracize those

living, or believed to be living, with HIV/AIDS. Such acts constitute discrimination based on

presumed or actual HIV-positive status and violate human rights.

Inter-linkages between Stigma, Discrimination and Denial

Manual on Advance

Counselling

for ICTC Counsellors

Meaning

of Stigma

Page 42

Stigma and discrimination tend to be used interchangeably. While stigma refers to a feeling of

inferiority raising a question of acceptance of the PLHA by others, discrimination is the act of non

acceptance and exclusion. Stigma and discrimination are self-perpetuating. A stigmatized group

experiences suffers discrimination, while discrimination underlines and reinforces stigma.

Discrimination leads to denial and violation of human rights. For example - in fear of being

stigmatized and hence discriminated, a PLHA often conceals his/her status and is thus denied of the

needed services and care. Stigmatizing and discriminatory actions, therefore, violate the

fundamental human right to freedom from discrimination. Additionally, discrimination directed at

PLHA or those believed to be HIV-infected, leads to the violation of other human rights, such as the

rights to health, dignity, privacy, equality before the law, and freedom from inhuman, degrading

treatment or punishment. Ensuring the protection, respecting and fulfillment of human rights is one

important way of combating HIV/ AIDS-related stigma and discrimination (Refer to Module Two for

more information on Rights Based Approach in HIV/ AIDS).

Figure – 3.4 Cycle of Stigma, discrimination and Violation of Human rights (Maluwa and Aggleton, 2000)

Intersection of HIV related stigma and discrimination with pre-existing

S & D associated with sexuality, gender, caste and poverty

To understand the ways in which HIV/ AIDS-related stigma and discrimination appear and the

contexts in which they occur, one needs to understand how stigma and discrimination in HIV/ AIDS