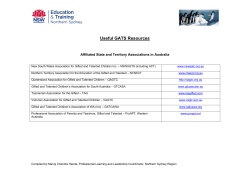

OUT-OF-SCHOOL EDUCATIONAL PROVISION FOR THE GIFTED AND TALENTED