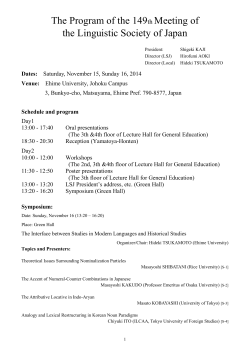

Draft program - Japan Studies Association