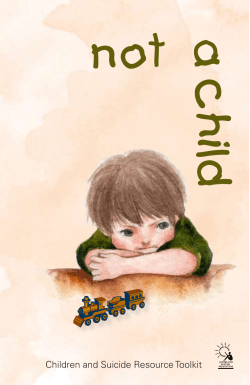

To Live To See the Great Day That Dawns: