Judicial local protectionism in China: An empirical study of IP cases

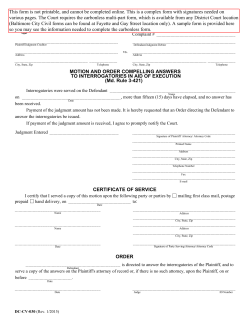

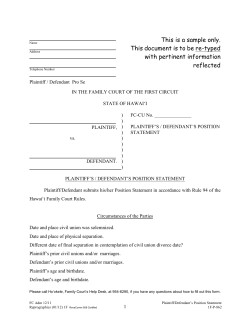

International Review of Law and Economics 42 (2015) 48–59 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect International Review of Law and Economics Judicial local protectionism in China: An empirical study of IP cases Cheryl Xiaoning Long a , Jun Wang b,∗ a b Wang Yanan Institute for Studies in Economics & School of Economics, Xiamen University, China School of Economics, Xiamen University, China a r t i c l e i n f o Article history: Received 1 May 2014 Received in revised form 20 September 2014 Accepted 23 December 2014 Available online 3 January 2015 Keywords: Judicial local protectionism Intellectual property Chinese case law a b s t r a c t Based on an empirical study of intellectual property cases published in the Bulletin of the People’s Supreme Court of China (the PSC) since 1985 as well as a large sample of intellectual property cases collected from five Chinese provinces filed during 1994–2009, this study finds that in first instance cases whether the plaintiff’s residence coincides with the court’s location has a positive and significant impact on whether the plaintiff gets a favorable ruling, after controlling for various plaintiff and defendant characteristics. As the findings are robust to various tests, they provide consistent evidence for the existence of judicial local protectionism in China. On the other hand, no significant impact of plaintiff location on trial outcome is found in appeals rulings for the IP cases. Instead, the appellate courts are found to redress the local protectionism problem in the first instance rulings in the PSC cases, thus offering support for the argument that the case law developed by the People’s Supreme Court aims at providing correctional mechanisms at the higher level to remedy the wrongs perpetrated at the lower level judiciary. The empirical results using the larger five-province sample, however, fail to find the rectifying effect of the appellate courts, suggesting that the goal of the PSC has yet to be achieved in many Chinese regions. These findings provide new insights for the relationship between law and development. © 2014 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 1. Introduction China’s rapid economic growth in the past thirty years has attracted scholars from different fields to offer explanations and to study impacts, including experts who explore the relationship between law and development. But in contrast to China’s stellar economic performance, its courts have long been at the receiving end of criticisms, especially as the country increasingly relies on the legal system to resolve various disputes. Lack of judiciary independence, overlapping jurisdictions, and low quality of legal professionals are among the major issues raised by critics, and the quality of rule of law is considered low by many (Orts, 2001; Lubman, 2006; Clarke et al., 2008). In particular, as a natural outcome of these legal issues, judicial local protectionism has remained prevalent over time and thus has attracted the attention from scholars in law, political science, and economics as one of the most serious problems plaguing the Chinese legal system (Chow, 2003; Zhang, 2003; Gechlik, 2005; Wang, 2008). The China ∗ Corresponding author at: School of Economics, Xiamen University, China. E-mail addresses: [email protected] (C.X. Long), [email protected] (J. Wang). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.irle.2014.12.003 0144-8188/© 2014 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. case thus seems to challenge the conventional wisdom on how law relates to development, as stated in the Rights Hypothesis, i.e., by providing property and contract protection, a well-functioning legal system is the key to a region’s sustained economic development (North, 1990; Hall and Jones, 1999; Acemoglu et al., 2001). In the current study, we examine the issue of judicial local protectionism by analyzing two samples of intellectual property cases adjudicated in China between 1985 and 2011, covering 23 provinces. In one sample, we use all the intellectual property cases included in the Bulletin of the People’s Supreme Court of China between 1985 and 2011, whereas the other sample includes all the IP cases posted online for the five major provinces of Fujian, Shandong, Henan, Hunan, and Sichuan between 1994 and 2009. To preview our empirical results, we find that in first instance cases when the plaintiff’s residence coincides with the court’s location, their probability of winning the case is significantly higher than in a case when the plaintiff’s residence is different from the court’s location, and such findings are robust to different samples and different specifications. The second set of findings relates to the role of the appeals courts. We find no significant impact of plaintiff location on trial outcome in appeals rulings for the IP cases. Instead, in the PSC cases, the appellate courts are shown to redress the local protectionism problem found in the first instance rulings. The C.X. Long, J. Wang / International Review of Law and Economics 42 (2015) 48–59 empirical results using the larger five-province sample, however, fail to find the rectifying effect of the appellate courts. Compared to existing studies on judicial local protectionism, we not only give more direct evidence for the existence of judicial local protectionism using a larger and more representative sample of cases, but more importantly, we study appeals courts as well as first trial courts in reaching legal judgments and explore their different roles in impacting the problem of judicial local protectionism. As one sample includes cases selected by the People Supreme Court (PSC) for publication and circulation among lower level courts, our study also helps shed light on the role of the PSC in China’s legal system and its development. Specifically, we offer support for the argument that the case law developed by the People’s Supreme Court aims at providing correctional mechanisms at the higher level to remedy the wrongs perpetrated at the lower level judiciary. But there is also evidence that the admirable goal of the PSC has yet to be achieved in many Chinese regions. Because we observe first instance trials, appeals rulings, as well as PSC’s case selection decisions, our study allows a more comprehensive exploration into the functioning of different levels of courts in the Chinese legal system, which permits a better understanding of how law regulates economic behaviors during China’s economic reform and social transformation. The observed attempt of the PSC in selecting and publicizing exemplary cases, where the appeals courts play the correctional role in rectifying the mistakes made by the lower courts, seems to provide support for an alternative theory linking law and development. Specifically, sustained economic development may induce the need for rule of law and thus legal development (Clarke et al., 2008). Finally, our research on the cases published by the People’s Supreme Court of China (the PSC) also provides materials for future studies on Chinese case law. Despite China’s history in following the continental law tradition since the late Qing dynasty, case law has emerged as an increasingly important component of Chinese law. In theory, judges should strictly interpret the stipulations in existing statutes and regulations to reach their judgment in any law suit. But in practice, the People’s Supreme Court in China have regularly selected legal cases to showcase the proper applications of both Chinese statutes and the PSC’s own judicial interpretations of statutes, by publishing these cases in the Bulletin of the People’s Supreme Court of China since 1985 and recommending them to lower courts as guidance in future cases. How important is this Chinese version of case law in reality? Our research on the PSC cases versus the five-province case sample can help evaluate the impact as well as the limitations of case law in China’s legal development. More generally, the findings can help evaluate the role of case law in development in general. The remainder of the paper is structured as follows: Section 2 reviews the related literature. Section 3 describes the court system and intellectual property laws in China, as well as the standards and procedures for selecting PSC cases and the role of these cases in influencing lower court rulings. Data sources and variable measurement are discussed in Section 4, while Section 5 presents estimation specifications and empirical findings. Section 6 concludes with a discussion on the implications of the empirical findings for economic theory and policy making. 2. Literature review The current study most closely relates to the literature on judicial local protectionism, which is local protectionism in the judiciary, where the local courts abuse their legal power to protect local interests (Chow, 2003). Regarding the sources of local protectionism in China, scholars have provided the following explanations. First, the current arrangements of fiscal decentralization 49 lead to interest conflicts between the central government and local governments, where local governments have the incentive to promote their own regional growth at the expense of other regions (Lee, 1998; Young, 2000; Yin and Cai, 2001; Poncet, 2005; Bai et al., 2008). Second, the promotion tournament among local leaders, where their promotion prospects are linked with regional economic growth, provides additional incentives for local protectionism (Zhou, 2004; Li and Zhou, 2005). Several features of the Chinese judiciary system further help explain why judicial local protectionism is a serious concern in the country. First of all, the lack of independence of the Chinese judiciary implies that the executive branch has the authority to make personnel and budgetary decisions for the courts. In addition, the locations of regional courts follow exactly the same administrative divisions as regional governments, which aligns one local court with one local government, giving the latter full control of the former (Zhang, 2003; Gechlik, 2005; Wang, 2008). Scholars have also studied the impact of local protectionism. Young (2000) find that it has led to market divisions and distortions. Bai et al. (2004) argue that governments in regions with high profit industries or a larger state sector are more inclined to provide local protectionism, which lead to a lower degree of specialization in these same regions. Following the same logic, Hu and Zhang (2005) show that the trade barriers erected by local governments in protecting their own regional interests have reduced the gains from trade among regions, as all regions now set up their own independent economic structures, resulting in much overcapacity. Due to lack of information, the above studies on local protectionism mostly rely on economic data to proxy the degree of protectionism (also see Naughton, 2003, for instance). On the other hand, most studies on judicial local protectionism are based on legal or political analyses, which tend to be strong in description but lacking in diagnostics. A small number of economic studies empirically examine judicial local protectionism in China. Chen et al. (2009) focus on listed firms entangled in legal cases and find that the stock prices of firms more likely to benefit from judicial local protectionism experience less fluctuation than those of other firms. Zhang and Ke (2002) adopt the approach of case analysis. Using a sample of economic legal cases from a basic court in Beijing, which were adjudicated during a 7-month period, the authors find that the winning rate of local firms (38.4%) is higher than that of non-local firms (25.9%). The discussion above suggests that existing research on the patterns, causes, and effects of local protectionism suffers from two problems. First of all, most studies rely on regional economic data to explore the issues, thus can only provide indirect inferences regarding the existence and patterns of local protectionism (Young, 2000; Yin and Cai, 2001; Naughton, 2003; Bai et al., 2004; Hu and Zhang, 2005; Poncet, 2005; Bai et al., 2008; Chen et al., 2009). Relatedly, as such economic proxies can only indirectly measure protectionism, research findings oftentimes differ depending on what data and proxies are used in the study. Furthermore, these studies do not address judicial local protectionism specifically. The second problem relates to the small number of studies that collect direct evidence of judicial local protectionism using case analysis. The small sample of cases included and the narrow regional scope covered challenge the generality of their empirical findings. For example, with data limited to a single court in Beijing and the time period focused to a 7-month period, we will not be able make nation-wide inferences about judicial local protectionism based on the Zhang and Ke (2002) study. Neither can we study patterns and variations in protectionism across regions or over time. In the sections below, we will attempt to address these two problems using two data sets. The first data set includes 50 C.X. Long, J. Wang / International Review of Law and Economics 42 (2015) 48–59 intellectual property cases published in the Bulletin of the People’s Supreme Court of China between 1985 and 2011, while the other data set covers a large number of IP cases from five major Chinese provinces spanning the time period of 1994–2009. These two data sets cover a much longer time period and much wider geographic scope, thus offering richer information regarding the patterns of judicial local protectionism. The second body of literature that the current study contributes to is that on law and development. Three alternative arguments have been made regarding how law relates to economic development. The Rights Hypothesis maintains that a well developed legal system is a prerequisite for sustainable economic growth (Hall and Jones, 1999; Johnson et al., 2000; Acemoglu et al., 2001; Easterly and Levine, 2003; Rodrik et al., 2004). Clarke et al. (2008), however, propose that in the case of China, it is economic growth that has induced legal development. A third argument combines the above two theories to suggest a more complex relationship between law and development as follows: In the early stage of economic development, the role of law is secondary and its development is a result of economic growth; but as the economy expands and matures, it becomes crucial that a well functioning legal system is established to provide protection for property and contracting rights, which is needed for sustainable growth (Li and Li, 2000; Li et al., 2003; Li, 2004). The reason that the Rights Hypothesis does not apply in the early stage of economic development, according to these authors, is the existence of alternative governance mechanisms that can substitute for the formal court system such as social networks. Partly to explore which of these theories best fits the Chinese reality, Long (2010) finds empirical evidence showing that firms located in regions with better courts tend to invest, invent, and expand more, supporting the validity of the Rights Hypothesis. But it is equally likely that having passed the stage of early development where the rule of law is dispensable, China has now entered the reign of the Rights Hypothesis, as Li and Li (2000) would argue. Furthermore, the study sheds no light on how the Chinese court system has improved from almost non-existence in the 1970s to the point of offering reasonable protection for firms and individuals. Thus, the relationship between law and development in China is still a relatively novel research area. By examining the functions of different levels of courts in the Chinese system, especially the role played by the People’s Supreme Court, the current study can produce more information and empirical evidence for this field of research. Additionally, the study of the detailed PSC cases in the current research contributes to the literature on case law and its importance in China’s legal and economic reforms. In the literature on law and development, the role of the common law system in promoting economic efficiency has been particularly emphasized, as it has been given theoretical support in evolutionary theory based arguments as follows: When economic efficiency can be gained by reversing the current ruling in the precedent, litigants in related cases will have more incentives to go to court; while their counterparts in cases with efficient precedent rulings are more likely to settle cases out of court. As Rubin (1977) puts it, “if rules are inefficient, parties will use the courts until the rules are changed; conversely, if rules are efficient, the courts will not be used and the efficient rule will remain in force.” In other words, although the common law system gives great precedential weight to prior cases and standing rulings, it is the legal precedents with economically efficient rulings that gain more secure status for future reference, whereas the less efficient rulings get repeatedly challenged in court through appeals or by new litigants. As a result, precedent based common law has the tendency to evolve toward economic efficiency (Rubin, 1977). Although China’s legal system has largely followed the continental law tradition, it has long been debated as to whether China should adopt a system of case law. Most scholars in the debate support such a system, and their arguments range from practical necessity (Liu, 2001; Zhang, 2002), to international references (Zhang, 2002), and to historical experiences (Wang, 2005). In reality, the legal cases published by the PSC since 1985 have served as models and have provided guidance for lower courts in subsequent cases, very much like the role played by legal precedents in common law countries. In the words of Mr. Ren Jianxin, who served as the PSC chief justice between 1988 and 1998: “A set of illustrative cases have been published in the PSC Bulletin, which have helped provide guidelines for court trials” (Ren, 1991). And in 2010, the reference value of the published cases was further bolstered by the issuance of the PSC’s “Provisions of the Supreme People’s Court on Case Guidance”. Based on an analysis of specific administrative license cases, Chen (2011) argues that the PSC Bulletin cases have a real impact on the rulings of similar cases filed in lower courts. Additionally, using a survey conducted in Shanghai, Yuan (2009) reports that a majority of local judges (51.4%) have used the PSC cases as references in reaching their rulings, while another 37.1% have consulted the Bulletin cases yet did not find cases that are similar enough as references. These PSC cases thus may be appropriately referred to as the case law in China, which seems to play an important role but through a route drastically different from that in common law countries. In the laissez-faire market-like common law system, litigants and judges act individually to make litigation and ruling decisions, which then lead to economically efficient outcomes for society according to the evolutionary argument. In contrast, the Chinese legal system relies more on a centrally planned model to improve judiciary quality, where good rulings from all over the country are selected at the top level and then sent to lower level courts to be studied and followed. Instead of the market competition among judges (who compete for better rulings and thus more citations) and among litigants (who resort to court or settlements for higher economic gains), the superior abilities of judges at the top level are relied on to deliver better rulings throughout the nation. While much research has been done to compare the performance of the market system versus the planned system in promoting economic growth, very little is known about the relative efficacy of the two approaches in implementing case law: market competition in case precedents versus central selection of cases. The current study makes the first attempt at studying the effectiveness of the Chinese case law, using judicial local protectionism as an example. In addition, as we have a larger sample of cases that are geographically more representative of the whole nation than those used in previous studies, we will be able to offer a more comprehensive and objective evaluation of the role of case law in China. 3. Institutional background 3.1. Litigation procedures in Chinese courts and intellectual property laws in China There are four levels of people’s courts in China, including basic courts at the county or district level, intermediate courts at the prefectural city level, higher courts at the provincial level, and the supreme court in Beijing. For intellectual property cases, which are the research focus of the current paper, the actor sequitur forum rei doctrine is followed in determining the location of the suit, as in other civil litigations. In other words, the plaintiff was to file a case of first instance at the place where the defendant usually resides C.X. Long, J. Wang / International Review of Law and Economics 42 (2015) 48–59 (see Article 21 of the Civil Procedure Law of the People’s Republic of China).1 While a civil case usually starts its court proceedings at a basic court in China, the court of first instance for intellectual property cases is normally an intermediate court, based on the supreme court’s rules regarding court jurisdictions over IP cases. According to the rules, the courts of first instance for patent cases are intermediate courts in the capital cities of each province or autonomous region, intermediate courts in the districts of the provincial level cities, as well as other intermediate courts designated by the People’s Supreme Court. For copyright and trademark cases, the courts of first instance include all intermediate courts, and in addition the higher courts at the provincial level can grant jurisdictions to certain basic courts depending on local needs. The justification for starting an IP case in an intermediate court is the complexity and technical knowledge requirement of the cases, which may be beyond the capacity of basic courts. In civil proceedings, the Chinese courts follow the rule whereby the court of second instance is the court of last instance (see Article 11 of the People’s Court Organization Law of the People’s Republic of China). If a party is not satisfied with the judgment of the first instance trial, they may bring an appeal to the people’s court at the next higher level. Judgments of the first instance trials become legally effective if, within the appeal period, none of the parties have appealed. Judgments from second instance trials (whether they are held in intermediate courts, higher people’s courts, or the Supreme People’s Court) and judgments from first instance trials in the Supreme People’s Court are judgments of last instance, i.e., legally effective judgments.2 The contemporary IP laws in China have been drafted starting in the 1980s. The first IP law to pass was the Trademark Law of the People’s Republic of China in 1982, and it has since been revised twice in 1993 and 2001, respectively. The Patent Law was first promulgated in 1984, and has since followed an 8-year cycle of revisions, with updates in 1992, 2000, and 2008. The last IP law to be ratified was the Copyright Law of the People’s Republic of China in 1990, and two revisions have been made in 2001 and 2010. Compared to other legal cases, intellectual property cases should suffer less from judicial local protectionism for the following two reasons: First, compared to other civil cases that can be tried in any court, only courts at the intermediate level or above have the jurisdiction over most IP cases. Second, the lack of judiciary independence implies that compared to higher level courts, lower level courts will experience more intervention from various government agencies, thus potentially experience more judicial local protectionism. Therefore, it more difficult to discover the existence of local protectionism by focusing on IP cases. But if we find corroborative results in these cases, then it is convincing evidence for the existence of judicial local protectionism in China. 3.2. Selection standards, procedures, and role of PSC Bulletin cases Starting in 1985, the People’s Supreme Court has been selecting a sample of cases from different fields of law to be published in the Bulletin of the People’s Supreme Court of China, which is the official gazette of the People’s Supreme Court of China published by the PSC’s administrative department, first quarterly, then bimonthly since 1999, and then monthly after 2004. The selection 1 Occasionally, the location of the suit can be the place of contract performance, the place of payment, or the place of tort. But in the vast majority of cases, it is the residence of the defendant that determines the location of the suit. 2 According to Article 199 of the Civil Procedure Law of the People’s Republic of China, if a party thinks that a legally effective judgment or ruling has errors, he may petition the people’s court at the next level for retrial. As none of the cases studied in this paper involves retrials, we do not discuss this complex issue here. 51 procedures for the PSC Bulletin cases are as follows: Cases are first recommended by local and provincial level courts to the editorial board of the PSC Bulletin, based on the following criteria: the correct application of the law, and the importance, complexity, or novelty of the case. The editorial board, usually consisting of former judges and legal professionals, then conducts some preliminary examination to toss out those cases considered unworthy of publishing, and categorizes the remaining cases into different fields to send to the proper adjudication divisions for consideration by judges familiar with the corresponding law. Next, the cases judged to be appropriate are submitted to the director (or the chief judge) of the corresponding adjudication division for approval, who then presents the approved cases to the PSC vice chief justice in charge of the corresponding field for confirmation.3 As a result, the cases included in the PSC Bulletin are by no means a random sample of all the legal cases filed and adjudicated in the Chinese court system. Instead, they cover a set of legal cases that are most commonly encountered, most complex, or most novel. And as the law has been correctly applied in the final ruling for all these cases, they also demonstrate the highest standards of legal judgments covering various areas of law in China. This selective set of cases has significant importance to other Chinese legal cases in general. Theoretically, there are two reasons why local courts will need to pay close attention to these PSC cases. First of all, the People’s Supreme Court supervises the functioning of all other courts, as stipulated by the Chinese Constitution, and the PSC uses the rates of retrial and reversal (where the lower court’s ruling is determined to be incorrect) as important standards for evaluating the performance of lower courts. Furthermore, whenever there is ambiguity in the law, the PSC has the authority to provide the ultimate interpretation, hence it is important to be consistent with the PSC. In reality, the PSC Bulletin has been fairly timely in selecting and publishing cases that help clarify new statutes, especially since it was published at a quarterly or monthly interval in the past two decades.4 Additionally, Yuan (2009) and Chen (2011) both provide evidence that the PSC cases do provide meaningful guidance to local courts in case rulings. And the former PSC chief justice Ren Jianxin also stated the following: “A set of illustrative cases have been published in the PSC Bulletin, which have helped provide guidelines for court trials” (Ren, 1991). The discussion above has two implications for the empirical analysis in the current study. On the one hand, the problems during the PSC cases’ first instance trials to be exposed by our empirical study most likely will have nation-wide prevalence, by the relevancy standard for selecting these cases. On the other hand, the goal to serve as references and guidelines for other court cases suggests that the PSC Bulletin cases may not be representative of the nation-wide cases, as far as the ultimate judiciary outcomes, i.e., the appellate rulings, are concerned. Therefore, we will need to carefully consider these implications in the part of our analysis below that relies on the set of intellectual property cases published in the PSC Bulletin. 4. Information sources and data description In the attempt to investigate the issue of judicial local protectionism through a study of case law, we focus on intellectual 3 Before 1998, further discussion and approval by the PSC’s trial committee were also required before a case was published in the Bulletin. 4 For example, the case of Liu Bingzheng v. Beijing Kangda Automobile Installation & Repair Factory published in July 1989 (the 3rd issue of PSC Bulletin in 1989) is ¨ Contract Lawt¨ hat was enacted on November 1, an application of China’s Technology 1987. On the other hand, the case of Dongfang Computer Technology Research Institute v. Hengkai Company and Hengkai Business Department was published in the 3rd issue of PSC Bulletin in 1995 to provide an application of the “Regulation on Computer Software Protectiont¨ hat went into effect on October 1, 1991. 52 C.X. Long, J. Wang / International Review of Law and Economics 42 (2015) 48–59 property cases for two main reasons. First, the IP area is where the Chinese legal system aligns the best with the international standards in terms of the quality of statutes, so we do not need to worry about biases caused by deficiencies in the related laws (Pistor and Xu, 2002). Second, the three types of IP cases, patent, copyright, and trademark, are much more comparable than other types of cases, thus allowing us to control for variations based on observable case characteristics. To study different aspects of the issue, we construct two samples of legal cases, the PSC Bulletin sample and the five-province sample. To collect case information, we use the Peking University Fayi Database by choosing cases involving IP property disputes, contract disputes, or torts. The first sample of cases comes from the Bulletin of the People’s Supreme Court, and we construct the sample by limiting the case publication source in the Fayi Database to the PSC Bulletin. We are able to find 102 cases that were filed between 1986 and 2010, among which 28 cases only involve first instance trials and 74 cases involve both first instance trials and appeals. Through careful reading of each legal judgment, we manually collect information on case type (patent, copyright, or trademark), dates of filing and ruling for first trial, dates of filing and ruling in appeal, number, location, and type of plaintiffs, number, location, and type of defendants, damages demanded by plaintiff, winner in each trial, location and level of court, and so on. Based on such information, we then construct additional variables to use in the empirical analysis. In particular, whether the locations of the plaintiff or the defendant match that of the court is the variable of most interest to us, and we generate the indicator dummy as follows: The plaintiff same location as court variable takes the value of 1 if the plaintiff’s location belongs to the same geographic administrative division that corresponds to the court, and it takes the value of 0 otherwise. As an example, if the court is at the intermediate level, we ask whether the location of the plaintiff belongs to the same prefectural city as the court, while in the case of a higher court, we ask whether the plaintiff locates in the same province. The defendant same location as court variable is constructed similarly, and in cases involving multiple plaintiffs or defendants, we give the same location variable a value of 1 as long as the above question has an affirmative answer for at least one of the plaintiffs or defendants.5 In particular, when an intermediate court at the prefectural level accepts cases from more than one districts or counties (which are both below the prefectural level), we judge the plaintiff or the defendant as sharing the same location with the intermediate court, only when the location of the plaintiff or the defendant belongs to the same district or county as the court. It is also crucial to measure which party wins a legal case. As in many cases, the final ruling may support only parts of the claims made by either party, it can be fuzzy as to which party comes out the winner. We use two alternative indicators to evaluate the outcome of each legal case. In the first approach, we first look at cases where one party appealed after the first trial and designate the appellee in the appeal as the winner; while for cases that ended after the first trial or cases where both parties appealed, we determine the plaintiff to be the winner as long as the court supports at least some of his or her damage demands in the first ruling. Alternatively, we compute the ratio between the amount of damage demanded by the plaintiff and the amount of damage granted in the ruling, and use the ratio as the win rate of the plaintiff. While the first measure is more in line with the common idea of a win in legal cases, 5 These criteria are more conservative. By contrast, if we use the prefecture-level administrative region as the criterion to judge whether the plaintiff or defendant sharing the same location with court, it is more likely to appear that the plaintiff or defendant did not share the same location with court in the appeal. However, the results do not changed in either case. Table 1 Summary statistics. Variable Panel A: PSC sample variables Plaintiff win in 1st trial Plaintiff win in appeal Damage granted/damage requested in 1st trial Damage granted/damage requested in appeal Plaintiff same location as court in 1st trial Defendant same location as court in 1st trial Plaintiff same location as court in appeal Defendant same location as court in appeal Patent case Copyright case Trademark case First trial in coastal region Appeal in coastal region Distance between plaintiff and court in 1st trial Distance between defendant and court in 1st trial Distance between plaintiff and court in appeal Distance between defendant and court in appeal Plaintiff is firm Defendant is firm Plaintiff is SOE Plaintiff is private firm Plaintiff is foreign firm Defendant is SOE Defendant is private firm Defendant is foreign firm Obs. Mean S.D. Min Max 102 74 86 0.69 0.61 28.39 0.47 0.49 34.55 0 0 0 1 1 100 57 29.57 32.52 0 100 102 0.50 0.5 0 1 102 0.83 0.37 0 1 74 0.66 0.48 0 1 74 0.95 0.23 0 1 102 102 102 102 74 102 0.34 0.31 0.34 0.81 0.80 1.68 0.48 0.47 0.48 0.39 0.40 3.33 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 11.94 102 0.18 0.92 0 8.87 74 1.53 3.05 0 11.41 74 0.23 0.46 0 1.89 102 102 102 102 102 102 102 102 0.71 0.92 0.24 0.21 0.26 0.44 0.40 0.07 0.46 0.27 0.43 0.41 0.44 0.5 0.49 0.25 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0.65 0.54 0.43 0.31 0.27 0.45 0.48 0.50 0.50 0.46 0.44 0.50 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 0.68 0.47 0 1 0.67 0.47 0 1 0.87 0.34 0 1 0.61 0.84 0.49 0.37 0 0 1 1 Panel B: Five provinces sample variables 449 Plaintiff win in 1st trial Plaintiff win in appeal 449 449 Patent case 449 Copyright case 449 Trademark case 449 Plaintiff same location as court in 1st trial 449 Defendant same location as court in 1st trial 449 Plaintiff same location as court in appeal 449 Defendant same location as court in appeal 449 Plaintiff is firm 449 Defendant is firm the second measure provides a continuous and thus more nuanced view of the legal outcome. In addition, to ensure that the results of first trial and appeal are comparable, instead of using the title of appellant and appellee, we continue to use the titles of plaintiff and defendant in the appeal. Panel A in Table 1 provides descriptive statistics for case characteristics in the PSC sample. It is clear from the table that although plaintiffs win in the majority of the cases (over 60%), their damage demands are only partially supported by the court (less than 30%). In the first instance trials, the court is in the same location as the defendant in over 83% of the cases, largely consistent with the actor sequitur forum rei doctrine. The small proportion of cases tried in courts outside of the defendant’s location are mainly due to the lack of intermediate courts with jurisdiction over patent cases where the defendant resides. As expected, the percentage of plaintiffs that share the court’s location is substantially lower than the defendants. C.X. Long, J. Wang / International Review of Law and Economics 42 (2015) 48–59 53 113 8 7 7 100 8 8 7 6 6 5 5 4 5 4 4 3 3 3 76 Number of cases 50 Number of cases 4 6 6 95 3 24 22 2 17 2 2 75 1 1 1 1995 1 1 4 6 2 1 2010 2009 2007 2008 2006 2004 2005 2002 2003 2001 2000 1998 1999 1997 1996 1995 1993 1994 1991 1989 1990 1987 1988 1986 2009 2008 2007 2006 2005 2004 2003 2002 2001 2000 1998 1999 0 0 1 1996 1 1994 11 Fig. 3. Distribution of first instance cases over time (five province sample). Fig. 1. Distribution of first instance cases over time (PSC sample). plaintiff location information, we obtain a sample of 449 cases. We then manually collect information on case type, plaintiff location, defendant location, court location in both trials, time of filing, time of termination, and case outcome. Figs. 3 and 4 give the temporal and geographic distributions of the legal cases in the five-province sample, while Table 1, Panel B gives descriptive statistics for the sample. As Fig. 3 indicates, the cases are distributed over the period of 1994–2009, with substantially more cases coming from 2001 to 2008, especially during 2004–2007. Geographically, the five provinces span the eastern, central, and western regions of the country, also including both northern and southern provinces from China. And as shown in Fig. 4, each of these provinces also has a sizable set of IP case filings so that not a single region or a small number of regions dominate the sample. In this aspect, the five-province sample is more representative of the average Chinese IP cases, as compared to the PSC sample. Panels A and B in Table 1 indicate several differences between the five-province sample of cases and the PSC Bulletin sample. The win rates for the plaintiff in both the first trial and the appeal tend to be lower in the five-province sample, and so are the probabilities of plaintiff and defendant being in the same location as the court in both trials. Furthermore, both the plaintiff and the defendant are more likely individuals in the five-province sample. These patterns suggest that the PSC cases are most likely selected from larger regions, which have their own courts, and they also tend to be larger cases involving firms rather than individuals. Although the PSC case sample lacks the representativeness of average nation-wide cases, detailed information regarding case characteristics such as ownership type of the litigating parties and so on is available for cases included in the sample, which allows us to analyze several important issues. Therefore, we will use both 150 30 While the IP cases in the sample are evenly distributed among patent, copyright, and trademark cases, their geographic distribution is largely skewed toward the coast. Regarding party identities, while plaintiffs are pretty evenly distributed across individuals, state owned enterprises (SOEs), private firms, and foreign firms, defendants are predominantly SOEs and domestic private firms. Finally, the distance between the plaintiff (defendant) and the court further confirms the relevance of the actor sequitur forum rei doctrine, as the defendant tends to be located substantially closer to the court, relative to the plaintiff. Figs. 1 and 2 further give the temporal and regional distributions of the legal cases included in our sample. Although there is no clear pattern in how the cases distribute over time, we can see that significantly more cases come from Beijing, Shanghai, and Jiangsu. In the section on robustness checks, we will address the question of whether cases from these three regions dominate the findings in the current study. Because the sample of IP cases are those published in the Bulletin of the People’s Supreme Court, one may challenge whether these cases are representative of all the IP cases filed in China. To address this issue, we collected information for all IP cases filed in the five provinces of Fujian, Shandong, Henan, Hunan, and Sichuan that have been made publicly available to construct the second case sample. Our information source is again Beida Fayi, and we use IP contract, property, or tort disputes as the search keywords as before, but also require the cases to be filed and tried in one of the five provinces listed above, which cover the western, middle, and eastern regions, and also span northern and southern China. To allow the comparison between first trial outcomes and appeal rulings, we also limit the cases to those that went to appeals. After deleting repetitive cases and those without appeals or without 29 137 4 3 1 1 1 55 4 2 1 1 Xizang 3 Shaanxi 2 Neimeng Hainan 2 Helongjiang 1 Hebei 1 83 66 2 1 Fig. 2. Distribution of first instance cases across provinces (PSC sample). Sichuan Shandong Hunan Henan Fujian 0 Yunnan Zhejiang Sichuan Shanxi Shanghai Shandong Liaoning Jilin Jiangsu Hunan Guangdong Fujian Anhui Beijing 0 1 Guangxi 5 2 Number of cases 50 100 17 Tianjin Number of cases 20 10 108 18 Fig. 4. Distribution of first instance cases across provinces (five province sample). 54 C.X. Long, J. Wang / International Review of Law and Economics 42 (2015) 48–59 Table 2 Location and plaintiff win. Defendant location PSC Sample Panel A Same as court Different from court Panel B Same as court Different from court Plaintiff location First trial Same as court Different from court Same as court Different from court Total Appeal same as court different from court Same as court Different from court Total Five provinces sample First Trial Panel A Same as court Same as court Different from court Different from court Same as court Different from court Total Appeal Panel B Same as court Same as court Different from court Different from court Same as court Different from court Total Number of observations Plaintiff win (%) 45 40 6 11 102 71.11 60 66.67 90.91 68.63 47 23 2 2 74 63.83 52.17 100 50 60.81 153 152 50 94 449 62.75 55.26 35.05 75.53 65.48 266 123 35 25 449 54.14 53.66 51.43 56 53.9 the PSC case sample and the five-province sample in the empirical analysis below to address the related issues. 5. Empirical findings 5.1. Empirical evidence for existence of judicial local protectionism We now empirically explore whether the court plays a significant role in helping a local litigant win a legal case in China, based on both the sample of IP cases selected by the PSC and the fiveprovince sample. Using the case outcome measures discussed in Section 4, we will study whether a plaintiff is more likely to win in a case filed in the local court. This is a feasible strategy because the actor sequitur forum rei doctrine is adopted in China, implying that the trial is normally held in the court local to the defendant. The exceptions occur when no courts in the defendant’s location have the jurisdiction over the IP case or when the parties choose to file the suit in the place of the dispute. Table 2 provides more information on the locations of the relevant parties in the legal cases as well as their probabilities of winning the cases. The focus of our analysis is on cases where the defendant shares the court’s location.6 For the PSC sample, among 85 such cases of first instance, the plaintiff wins the case with a probability of 71% when they are from the same location as the court, but their win rate drops to 60% if the suit is filed in a non-local court. For the 70 such cases that went to appeals, the plaintiff’s win rate falls from 64% to 52% between suits filed in local courts and those filed in non-local courts. A simple comparison of numbers thus suggests that going to court in their own locality increases the plaintiff’s win rate in a legal case by a substantial margin, as high as 10 percentage points. Similarly, for the five-province sample in first trials, plaintiffs from 6 This is potentially a selection issue here, i.e., plaintiffs from outside the region will only sue defendants in the region if they have a strong case (assuming there is local protectionism). But this will cause a bias against finding the results to be shown later, thus strengthening our empirical findings. the same location as the court have a higher likelihood of winning (63%) than those from different locations (55%). In contrast, the difference in appeal win rate is not substantial (54.1% vs. 53.7%). To control for other factors that also affect the plaintiff’s win rate and study the patterns and causes of judicial local protectionism, we now turn to an empirical examination of the data using econometric models. We begin with the first instance trials to study how court location affects the plaintiff’s probability of winning, including only cases where the defendant shares the court’s location. Specifically, we estimate the following model, winner plain 1 = ˇ0 + ˇ1 ∗ Same plaincourt 1 + X + ε, (1) where winner plain1, the plaintiff win measure in the first instance, is the dependent variable, while the main explanatory variable of interest is same plaincourt1, the dummy variable indicating whether the court is in the same location as the plaintiff. The model also controls for a set of other explanatory variables, X, while ε is the residual term. To take into consideration of the national level changes over time, we include time fixed effects as well, corresponding to the year in which the filing of the case began or ended, i.e., the beginning year or the ending year, in different specifications. The estimation method is the linear probability model instead of the logistical model to avoid the reduction in sample size when the outcome variable does not change along certain explanatory variables.7 Consistent with other studies on trial outcomes (Zhang and Ke, 2002; Lu et al., 2011), we include in the set of explanatories, X, the following variables that also affect the win rate of the plaintiff: the category of intellectual property involved in the legal case (patent, copyright, or trademark), region where the case was filed (whether the region is among the coastal provinces in China), identity type of the plaintiff (defendant), as well as the distance between the plaintiff (defendant) location and the court’s location. The IP category is included as different types of IP cases may have different win rates for the plaintiff. Whether the case was filed in the coastal region may impact the win rate due to regional variations in the degree of local protectionism, case load differential, and other factors. Following the conventional division, the coastal region includes Liaoning, Beijing, Tianjin, Hebei, Shandong, Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Fujian, and Guangdong, while the rest of China are in the inland region. For the identity type, we first divide the plaintiffs (defendants) into firms and individuals and then among firms further divide them by ownership type to state owned enterprises (SOEs), private domestic firms, and foreign firms. Clearly, the identity type of the plaintiff (defendant) has implications for the case outcome. While one would expect the Chinese legal system to have a bias against private firms in the earlier years of the reform era, the relationship between Chinese courts and foreign firms is more complex.8 On the one hand, foreign firms may be offered preferential treatment in the legal system, consistent with other preferential policies provided to foreign investors. On the other hand, foreign firms may experience a greater degree of judicial local protectionism for the very reason of being foreign. The distance variables are included to control for litigation costs that the two parties face during the legal proceedings, with a longer distance between one’s location and the court’s location implying higher costs. By using Baidu Map that is 7 Reassuringly, we obtain very similar estimates for marginal effects of court location on plaintiff win rates in various specifications using the probit model, although the significance level is sometimes reduced due to the slightly smaller sample size. 8 In cases where there are many plaintiffs or defendants who have diversified ownerships, we use information on the party that shares the same location with the court or has the strongest interest in the law suit. C.X. Long, J. Wang / International Review of Law and Economics 42 (2015) 48–59 55 Table 3 Plaintiff win rate versus location in first instance trials. Variables (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) Dep.var. = plaintiff win in first trial Plaintiff location same as court in 1st trial 0.276* (0.148) 0.340** (0.158) 0.401** (0.166) 0.009 (0.021) −1.876 (1.171) 0.202 (0.178) 0.007 (0.026) −1.574 (1.188) 0.288 (0.200) 0.048** (0.021) −1.937 (1.205) 0.143 (0.174) 0.303** (0.138) −0.341** (0.169) 0.035* (0.019) −0.144** (0.068) 0.149 (0.148) 0.241 (0.150) 0.357** (0.176) 0.001 (0.157) −0.024 (0.141) 0.212 (0.142) Yes 0.257* (0.145) 0.014 (0.158) Yes Defendant location same as court in 1st trial Distance between plaintiff and court in 1st trial Distance between defendant and court in 1st trial Patent case 24.676** (10.505) 2.210 (1.450) −173.615** (83.361) 27.374* (15.823) 0.051 (0.136) Yes 0.010 (0.021) −1.960 (1.222) 0.366 (0.278) −0.259 (0.326) 0.338 (0.206) −0.216 (0.319) 0.194 (0.146) Yes Yes 102 0.324 Yes 85 0.415 Yes 74 0.498 Copyright * plaintiff location same as court in 1st trial First trial in coastal region Individual vs. firm ownership controls Dep.var = win% 0.419* (0.220) Patent case * plaintiff location same as court in 1st trial Copyright case (6) 10.505 (10.752) −13.347 (10.323) Yes Yes End year FE Begin year FE Obs. R-squared Yes Yes 85 0.405 Yes 85 0.453 85 0.389 Notes: The dependant variable win% of Column 5 means damage granted/damage requested in1st trial. Standard errors are in parentheses. * Significant at 10%. ** Significant at 5%. *** Significant at 1%. accurate to the township level, we measure the direct-line distance between any two locations in kilometers. Table 3 Column (1) presents our baseline estimation results based on Eq. (1), using the PSC sample. The difference between Column (2) and Column (1) is that plaintiff and defendant identity types are measured in individuals versus firms in Column (1), while in Column (2) the ownership types of the firms are also controlled for. In columns (1) and (2), the coefficient of the plaintiff location variable is positive and significant at 10% level and 5% level, respectively. The impact is also economically important, with the plaintiff having a win rate about 30 percentage points higher in a case filed in a local court than in a case filed out of town, after controlling for other factors. Columns (3) and (4) in Table 3 present additional results supporting the same finding above. In Column (3), we replace the beginning year fixed effects with the ending year fixed effects, and obtain similar results as before; while in Column (4), we expand the sample size by including cases filed in courts away from the defendant’s location and controlling for an indicator for whether the defendant’s location is the same as the court. Again, the estimation results similarly show the positive and significant effect of same location on plaintiff win rate. We also explore the potential differences in judicial local protectionism among different types of IP cases in Column (5), by adding the interaction term between patent and plaintiff location as well as that between copyright and plaintiff location. Although the interaction terms are not significant, they are of the opposite sign of the plaintiff location coefficient. And the statistical test shows that while the plaintiff location has a positive effect on the win rate of trademark cases, the total effect of plaintiff location on a patent case or a copyright case is non-significant.9 Hence, different from 9 The F-statistic for H0 : ˇplaintiff location same as court + ˇpatent case*plaintiff location same as court =0 is 0.35 with p-value = 0.56, and the F-statistic for H0 : is 0.67 with ˇplaintiff location same as court + ˇcopyright case*plaintiff location same as court = 0 p-value = 0.42. the case in the U.S. where patent protection is the strongest, local protectionism is mainly observed in trademark cases in China. This is most likely due to the relatively low level of IP development in the country during the sample period, where competition in IP products still focuses on trademarks rather than patents or copyrights. Finally in Column (6), we replace the indicator for plaintiff winning the case with the ratio of damage granted in the ruling. The plaintiff’s location being the same as the court increases the ratio of damage granted by 25%, which is not only statistically significant but also economically important. To further test the robustness of the findings above, we now address the issue of how representative our sample are of cases nation-wide. First of all, we check whether the cases from Beijing, Shanghai, and Jiangsu dominate the PSC sample and thus impact the patterns discovered. Fig. 1 shows that 64 cases out of the total 102 IP cases collected from the PSC Bulletin are from Beijing, Shanghai, and Jiangsu. To see whether the patterns reported so far are mainly driven by cases from these three regions, we first delete cases from each of the three regions above in turn to rerun the analysis. In addition, we separate the 102 cases into the sample of Beijing, Shanghai, and Jiangsu cases and the sample of cases from other regions, and then use these two samples to redo the analysis. The estimation results are presented in Table 4, with Columns (1)–(3) using cases excluding Beijing, Shanghai, and Jiangsu, respectively, whereas Column (4) using the sample of Beijing, Shanghai, and Jiangsu cases, and Column (5) using the sample of cases from other regions. As shown in the table, the effect of plaintiff location remains significant in two of the five specifications, with the magnitude similar to that obtained before. In the other three specifications, the estimated effect is in the expected direction with similar estimate, suggesting that the lack of statistical significance is mainly due to the small sample size. We now use the larger sample of IP cases collected from five provinces to further test the robustness of the empirical findings discovered above. Table 5 gives the empirical findings based on this larger sample, where Columns (1) and (2) examine only cases with the defendant sharing the court’s location in the first trial, as 56 C.X. Long, J. Wang / International Review of Law and Economics 42 (2015) 48–59 Table 4 Beijing, Shanghai, and Jiangsu versus other regions (first instance trials). Variables (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) Dep.var.=plaintiff win in 1st trial Plaintiff location same as court in 1st trial Individual v. Firm Begin year FE Obs. R-squared 0.338* (0.189) Yes Yes 60 0.438 0.378*** (0.141) Yes Yes 72 0.439 0.201(0.146) Yes Yes 71 0.359 0.199(0.168) Yes Yes 52 0.547 0.552(0.318) Yes Yes 33 0.741 Notes: Samples excluding Beijing, Shanghai, or Jiangsu cases are used in Columns 1, 2 and 3, respectively, sample of Beijing, Shanghai and Jiangsu cases is used in Column 4, while sample of cases from other regions is used in Column 5. All models control for coastal region dummy, case type, and distance between plaintiff and court as well as that between defendant and court. Standard errors in parentheses. * Significant at 10%. ** Significant at 5%. *** Significant at 1%. Table 5 Sample of five province cases (trials of first instance). Variables (1) (2) (3) Plaintiff location same as court in 1st trial Defendant location same as court in 1st trial 0.123** (0.061) 0.120** (0.061) Yes Yes Yes 305 0.087 0.146** (0.073) 0.081 (0.076) Yes Yes Yes 305 0.099 (4) Dep.var. = plaintiff win in 1st trial Patent case Copyright case Individual vs Firm Begin year FE Province FE Obs. R-squared 0.093** (0.046) −0.229*** (0.049) Yes Yes Yes 449 0.116 0.092** (0.046) −0.214*** (0.050) 0.105* (0.058) 0.114* (0.061) Yes Yes Yes 449 0.125 Notes: Standard errors in parentheses. * Significant at 10%. ** Significant at 5%. *** Significant at 1%. implied by the actor sequitur forum rei doctrine, while the sample in Columns (3) and (4) includes all cases but controls for the defendant location. The coefficient for plaintiff sharing the same location as the court is positive and significant at 5% level in Columns (1) and (2), a finding largely replicated in Columns (3) and (4). Furthermore, a defendant local to the court significantly brings down the plaintiff’s win rate by 23% (Columns (3) and (4)), providing additional evidence for the existence of judicial local protectionism in Chinese courts of first instance. In comparison with the estimated effects from the PSC sample, the impact found in Table 5 is substantially smaller, which may be explained by two possible reasons: First, due to lack of information, estimations in Table 5 do not include as many as control variables as those using the PSC sample, thus it is difficult to directly compare the estimates. Second, it is also possible that cases with the most egregious mistakes have been included in the PSC sample, as reflected in the large and significant effect of plaintiff location on plaintiff win rate found for this sample. But in our view, the finding of significant effects of plaintiff location for the more representative five-province case sample, combined with the relevancy standard for selecting the PSC cases, provides sufficient evidence that judicial local protectionism still enjoys substantial prevalence in China. first trial, they can file an appeal in a higher level court. This may potentially rectify the problem of judicial local protectionism that we have observed in the trials of first instance, as the plaintiff who has grievances could request the upper level court to re-examine the case. We now empirically test this hypothesis and study the role of appellate courts in impacting judicial local protectionism in China. First, we use the following estimation model to study the potential existence of judicial local protectionism during the appeal: winner plain2 = ˇ0 + ˇ1 ∗ same plaintiffcourt2 + ˇ2 ∗ same defendantcourt2 + ˇ3 ∗ winner plain1 + X + ε (2) where winner plain2 is the dummy indicating plaintiff’s win in the appeal, while same plaintiffcourt2 and same defendantcourt2 are indicators for whether the location of the plaintiff or the defendant is the same as the court in the appeal.10 The case outcome from the first trial, winner plain1, needs to be controlled for, because it captures information on the strength of the case. Otherwise, the specification is similar to that of model (1). More importantly, we test whether the appeals court serves a remedial role in correcting judicial local protectionism in the lower 5.2. Judicial local protectionism in appeal cases According to the People’s Court Organization Law of the People’s Republic of China, if either party is unhappy with the ruling from the 10 We included the defendant location variable to keep as many cases in the sample as possible. Excluding the small number of cases where defendant location differs from the court’s location in appeals does not significantly change our results. C.X. Long, J. Wang / International Review of Law and Economics 42 (2015) 48–59 57 Table 6 Judicial local protectionism in appeals. Variables (1) (2) (3) (4) Dep.var. = plaintiff win in appeal −0.079 (0.189) 0.004 (0.469) 0.691*** (0.152) −0.085 (0.180) 0.074 (0.435) 0.733*** (0.135) Plaintiff location same as court in appeal Defendant location same as court in appeal Plaintiff win in 1st trial 0.009 (0.235) −0.243 (0.441) 0.975*** (0.179) 0.056 (0.262) −0.546** (0.259) Plaintiff location same as court in 1st trial Plaintiff win * plaintiff location same as court in 1st trial Ownership controls Individual vs. firm Begin year FE Obs. R-squared 0.021 (0.260) −0.280 (0.473) 0.947*** (0.199) 0.047 (0.293) −0.528* (0.278) Yes Yes Yes Yes 74 0.557 Yes Yes 74 0.624 Yes 74 0.566 Yes 74 0.628 Notes: All models control for coastal region dummy, case type, and distance between plaintiff and court as well as that between defendant and court. Standard errors are in parentheses. * Significant at 10%. ** Significant at 5%. *** Significant at 1%. court as follows: winner plain2 = ˇ0 + ˇ1 ∗ same plaintiffcourt2 + ˇ2 ∗ same defendantcourt2 + ˇ3 ∗ winner plain1 + ˇ4 ∗ same plaintiffcourt1 + ˇ5 ∗ (winner plain1 × same plaintiffcourt1) + gX + ε, (3) where we add to the explanatory variables the dummy of plaintiff having same location as the court in the 1st trial as well as its interaction with the plaintiff win in the 1st trial dummy. If the appellate court does serve the remedial function, we expect to see, ˇ5 , the coefficient of the interaction term, to be negative and significant. Again, other controls and specifications are similar to those in model (1). Table 6 shows results from estimating models (2) and (3) using the PSC cases, where the first two columns are based on model (2) and the last two columns are based on model (3). From Columns (1) and (2), we can see that there is no impact of the appeals court being in the same location as the plaintiff on the latter’s winning the appeal. And this pattern remains in Columns (3) and (4), which also include additional controls. Therefore, there is no evidence from the PSC case sample that judicial local protectionism also plagues the appellate courts in China. In Columns (3) and (4) of Table 6, the interaction term between the plaintiff’s win in the first trial and it having the same location as the court in the first trial is both negative and significant. To illustrate the importance of the interaction term, if the first trial was conducted in a court outside of the plaintiff’s location and the plaintiff won the trial, then its chance of winning in the appeal would be in the mid-90%. But if the plaintiff sued in a local court and won the first trial, then its win rate in the appeal would drop to about 40%, with all other factors being equal. This is in support of the argument that appeals courts play the role of rectifying judicial local protectionism that plagues lower level courts, which is one of the official functions an appeal should serve, as stipulated by the Civil Procedural Law of the people’s Republic of China, Article 170. Table 7 Beijing, Shanghai and Jiangsu versus other regions (appeal cases). Variables (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) Dep.var. = plaintiff win in appeal Plaintiff location same as court in appeal Defendant location same as court in appeal Plaintiff win in 1st trial Plaintiff location same as court in 1st trial Plaintiff win * plaintiff location same as court in 1st trial Individual vs. firm Begin year FE Obs. R-squared −0.506 (0.431) 1.450 (1.404) 1.078*** (0.273) 0.468 (0.424) −0.631* (0.362) Yes Yes 49 0.667 0.0667 (0.340) −0.109 (0.613) 0.839*** (0.264) −0.145 (0.356) −0.429 (0.341) Yes Yes 61 0.598 −0.105 (0.208) −0.199 (0.361) 1.068*** (0.173) −0.0218 (0.254) −0.435* (0.251) Yes Yes 62 0.821 0.141 (0.282) 0.149 (0.617) 1.062*** (0.217) 0.152 (0.328) −0.954** (0.398) Yes Yes 50 0.760 −0.778 (1.033) 1.778 (1.207) −0.333 (1.269) Yes Yes 24 0.881 Notes: Samples excluding Beijing, Shanghai, or Jiangsu cases are used in Columns 1, 2 and 3, respectively, sample of Beijing, Shanghai and Jiangsu cases is used in Columns 4, while sample of cases from other regions is used in Columns 5. All models control for coastal region dummy, case type, and distance between plaintiff and court as well as that between defendant and court. Standard errors are in parentheses. * Significant at 10%. ** Significant at 5%. *** Significant at 1% 58 C.X. Long, J. Wang / International Review of Law and Economics 42 (2015) 48–59 Table 8 Sample of five-province (appeals cases). Variables (1) (2) (3) (4) Dep.var. = plaintiff win in appeal Plaintiff location same as court in appeal Defendant location same as court in appeal Plaintiff win in 1st trial −0.013 (0.050) 0.058 (0.071) 0.378*** (0.049) Patent case Copyright case −0.013 (0.050) 0.067 (0.072) 0.383*** (0.050) −0.051 (0.059) −0.011 (0.063) Plaintiff location same as court in 1st trial Plaintiff win * plaintiff location same as court in 1st trial Individual vs firm Begin year FE Province FE Obs. R-squared Yes Yes Yes 449 0.168 Yes Yes Yes 449 0.170 0.015 (0.066) 0.052 (0.071) 0.376*** (0.064) −0.043 (0.088) 0.003 (0.097) Yes Yes Yes 449 0.169 0.020 (0.066) 0.061 (0.072) 0.379*** (0.065) −0.054 (0.059) −0.007 (0.064) −0.054 (0.090) 0.011 (0.099) Yes Yes Yes 449 0.171 Notes: Standard errors are in parentheses. * Significant at 10%. * Significant at 5%. *** Significant at 1%. Combined together, the results presented in Table 6 suggest that the appellate courts in China are not only less susceptible to judicial local protectionism, but also help to mitigate the problem in the lower level courts by reversing the rulings in cases that suffer from such a problem during appeals. But this is a picture painted by the PSC cases. Are they representative of typical cases adjudicated all over China? To answer this question, we will next look at the regional distribution of PSC cases more carefully. And in addition, we will resort to the five-province sample. Table 7 presents results from using the same specification as Table 6 but with various regional samples of the PSC cases. As in Table 4, Columns (1)–(3) use cases excluding Beijing, Shanghai, and Jiangsu, respectively, whereas Column (4) uses the sample of Beijing, Shanghai, and Jiangsu cases, and Column (5) uses the sample of cases from other regions. Similar to the finding in Table 6, none of these samples show evidence of judicial local protectionism during appeals. Regarding the rectifying role of the appellate courts, three samples (in Columns (1), (3), and (5)), all of which include cases from Shanghai, obtain results showing the reversal of rulings that may have been contaminated by judicial local protectionism in the lower court trials. In other words, the previous finding that appellate courts in China can correct the wrongs of lower level courts may be driven mainly by cases from regions with the highest frequency of IP cases such as Shanghai. Estimation results using the five-province sample are provided in Table 8, where Column (1) gives the baseline specification, Column (2) includes additional controls, while Columns (3) and (4) further control for the interaction between plaintiff win and plaintiff location in the first trial. None of specifications give evidence of judicial local protectionism in Chinese appellate courts, which is consistent with the previous findings. However, there is also no evidence of the correctional function of courts during appeals involving potential judicial local protectionism in any of the specifications. Given the much larger sample size relative to those in Table 4, where small sample sizes may account for the lack of statistical significance, the failure to find significant effects here should more appropriately be interpreted as evidence for the absent role of the appellate courts in correcting lower court mistakes. In contrast to the results in the previous section, where cases from different parts of China all provide evidence for the existence of judicial local protectionism, the empirical findings in this section give mixed evidence about the rectifying function of appeals courts in China. While the findings based on the PSC Bulletin cases showcase the appellate courts’ corrective roles, the results using different subsamples of the PSC cases suggest that such roles have been played with different degrees of success in different regions. Furthermore, the results based on the five-province sample provide additional evidence that the rectifying functions of Chinese appeals courts envisioned by the PSC are not well served nationally. Thus, the more appropriate interpretation of these results seems to be the following: The PSC Bulletin cases are selected and published for the very reason that the appellate courts involved in these cases have served their corrective roles appropriately, as required by law. As we should not expect all the cases to be solved like the exemplary cases, it is only natural that we do not observe the judicial local protectionism bias to be reversed in appeals for the larger five province sample. This more pessimistic view of the Chinese legal system is also supported by the previous finding that the reversal of lower court judgments involving potential judicial local protectionism is largely driven by the sample of cases from Shanghai and other regions with more IP cases, but absent in the sample of cases from other regions. Incidentally, the survey that supports the effective role of the PSC cases in impacting lower court rulings was conducted in no other place but Shanghai, which is reputed to have the highest quality legal services and thus may not be representative of the national average. 6. Conclusion Most previous studies on judicial local protectionism in China are either based on case studies from a single location or reliant on indirect measures of local protectionism. And there also lack empirical studies on how courts of different levels behave differently regarding judicial local protectionism. Using IP cases from the Bulletin of the People’s Supreme Court, between 1986 and 2010, as well as a larger sample of IP cases from five provinces, we empirically study how the plaintiff’s location versus the court impacts the plaintiff’s win rate in the first trial and in the appeal. The findings from both the PSC sample (regardless of whether the sample is from Beijing, Shanghai, and Jiangsu or from the other regions) and the five province sample confirm the existence of judicial local protectionism in the courts of first instance. Similarly, our C.X. Long, J. Wang / International Review of Law and Economics 42 (2015) 48–59 failure to find evidence of judicial local protectionism in appeals courts is robust in both samples. On the other hand, the rectifying function of the appellate court to reverse the lower court’s incorrect rulings due to judicial local protectionism is only observed in the PSC sample, or more specifically, in the sample of cases from Beijing, Shanghai, and Jiangsu, which are the regions with the largest number of IP case filings and arguably court services of the highest quality as well. These results help provide more insights to the relationship between rule of law and economic development in China. Based on daily experiences and anecdotal evidence, people tend to conclude that rule of law in China is of low quality. It is thus perplexing that the country has been able to achieve fast and steady economic development despite the lack of quality legal protection (Clarke et al., 2008). The belief of insufficient rule of law has its validity, as evidenced by the existence of judicial local protectionism, but there also exists correctional mechanisms at the higher level that are designed to remedy some of the wrongs perpetrated at the lower levels, as evidenced by our findings. In our empirical study, we find no evidence of local protectionism during the appeals cases. Furthermore, we find that the incorrect rulings likely influenced by judicial local protectionism have been reversed by the appeals courts, at least in the regions where intellectual property cases are filed with the highest frequency. By overruling the biased judgments made by the lower court, this thus reduces the damage caused by judicial local protectionism and provides more justice to society. Finally, by presenting these cases as the exemplary cases for lower courts to study and follow, the People’s Supreme Court of China seems to have taken as its primary goal to provide an open, fair, and just legal environment to help promote the sustainable economic growth in China. Thus from this perspective, the experience of China’s economic development is more in line with the growth induced legal development argument made by Clarke et al. (2008). The approach adopted by the PSC to help improve court quality is similar to the approach of pilot reforms followed by national adoption the nation’s economic leaders used in the early years of reforms, i.e., central selection of high quality cases to be followed by lower courts. While this creates a novel way of generating and using case law, as our findings based on the five-province case sample illustrate, there are limitations to the applicability and the effectiveness to such an approach. While some regions see more success in following the model cases, other cases lag behind. How to achieve more uniform improvement in the quality of legal services in China? More research is needed to address this and other related questions. Acknowledgement We appreciate the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 71273217). References Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., Robinson, J.A., 2001. The colonial origins of comparative development: an empirical investigation. Am. Econ. Rev. 91, 1369–1401. Bai, Chong-en, Du, Yingjuan, Tao, Zhigang, Tong, Sarah Y., 2004. Local protectionism and industrial concentration in China: overall trend and important factors. China Econ. Res. 4, 29–40 (in Chinese). Bai, Chong-en, Tao, Zhigang, Tong, Yueting Sarah, 2008. Bureaucratic integration and regional specialization in China. China Econ. Rev. 19, 308–319. Chen, Xinyuan, Li, Mochou, Rui, Oliver M., Xia, Lijun, 2009. Judiciary independence and the enforcement of investor protection laws: market responses to the 1/15 59 notice of the supreme people’s court of China. China Econ. Quart. 9, 1–28 (in Chinese). Chen, Yuefeng, 2011. The legal effect of public report case in the relationship with the inferior court’s judgment on similar cases. China Legal Sci. 5, 176–191 (in Chinese). Chow, Daniel C.K., 2003. Organized crime, local protectionism, and the trade in counterfeit goods in China. China Econ. Rev. 14, 473–484. Clarke, D.C., Murrell, P., Whiting, S.H., 2008. The role of law in China’s economic development. In: Loren, B., Rawski, T.G. (Eds.), China’s Great Economic Transformation. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp. 375–428. Easterly, W., Levine, R., 2003. Tropics, germs, and crops: how endowments influence economic development. J. Monet. Econ. 50, 3–39. Gechlik, Meiying, 2005. Judicial reform in China: lessons from Shanghai. Columbia J. Asian Law 19, 97–137. Hall, R.E., Jones, C.I., 1999. Why do some countries produce so much more output per worker than others? Quart. J. Econ. 114, 83–116. Hu, Xiangting, Zhang, Lu, 2005. Local protectionism and regional specialization: a model and econometric evidences. China Econ. Res. 2, 102–112 (in Chinese). Johnson, S., McMillan, J., Woodruff, C., 2000. Entrepreneurs and the ordering of institutional reform: Poland, Slovakia, Romania Russia and Ukraine Compared. Econ. Transit. 8 (1), 1–36. Lee, Pak K., 1998. Local economic protectionism in China’s economic reform. Develop. Policy Rev. 16, 281–303. Li, Shaomin, 2004. From relations to rules: a theoretical explanation and empirical evidence. In: Ham, Chae-hak, Bell, Daniel A. (Eds.), The Politics of Affective Relations: East Asia and Beyond. Lexington Books, Lanham, MD, pp. 217–230. Li, Shaomin, Park, Seung Ho, Li, Shuhe, 2003. The great leap forward: the transition from relation-based governance to rule-based governance. Org. Dyn. 33 (1), 63–78. Li, Shuhe, Li, Shaomin, 2000. The economics of Guanxi. China Econ. Quart. Q1, 40–42. Li, Hongbin, Zhou, Li-An, 2005. Political turnover and economic performance: the incentive role of personnel control in China. J. Public Econ. 89 (9), 1743–1762. Liu, Shiguo, 2001. Case law and legal interpretation: the discussion of creating case law in China. Legal Forum 2, 40–50 (in Chinese). Long, Cheryl Xiaoning, 2010. Does the rights hypothesis apply to China? J. Law Econ. 53, 629–650. Lu, Haitian, Pan, Hongbo, Zhang, Chenying, 2011. Political connections and judicial bias: evidence from Chinese corporate litigations, Working Paper. University of Pennsylvania. Lubman, S/, 2006. Looking for law in China. Columbia J. Asian Law 20, 1–91. Naughton, B., 2003. How much can regional integration do to unify China’s markets? How far across the river., pp. 204–232. North, Douglass C., 1990. Institutional Change and Economic Performance. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. Orts, W.E., 2001. The rule of law in China. Vanderbilt J. Transit. Law 34, 43–115. Pistor, Katharina, Xu, Chenggang, 2002. Incomplete law. Int. Law Polit. 35, 931–1013. Poncet, Sandra, 2005. A fragmented China: measure and determinants of Chinese domestic market disintegration. Rev. Int. Econ. 13, 409–430. Ren, Jianxin, 1991. Report on the work of the supreme people’s court. In: Delivered at the fourth Session of the Seventh National People’s Congress in April, (in Chinese). Rodrik, D., Subramanian, A., Trebbi, F., 2004. Institutions rule: the primacy of institutions over integration and geography in economic development. J. Econ. Growth 9 (2), 131–165. Rubin, P.H., 1977. Why is the common law efficient? J. Legal Stud., 51–63. Wang, David T., 2008. Judicial reform in China: improving arbitration award enforcement by establishing a federal court system. Santa Clara Law Rev. 48, 649–679. Wang, Zhiqiang, 2005. Case precedents in Qing China: rethinking traditional case law. Columbia J. Asian Law 19, 323–344. Yin, Wenquan, Cai, Wanru, 2001. The genesis of regional barriers in China’s local market and countermeasures. China Econ. Res. 6, 3–12 (in Chinese). Young, Alwyn, 2000. The razor’s edge: distortions and incremental reform in the People’s Republic of China. Quart. J. Econ. 115, 1091–1135. Yuan, Xiuting, 2009. The practice operation and evaluation of Chinese case guidance system: take the IP cases of people’s Supreme Court bulletin cases as objects. Stud. Law Bus. 2, 102–109 (in Chinese). Zhang, Qi, 2002. A comparative study on case law: a discussion of the significance, institutional basis, and operation of Chinese case law. J. Comp. Law 4, 79–94 (in Chinese). Zhang, Qianfan, 2003. The people’s court in transition: the prospects of the Chinese judicial reform. J. Contemp. China 12, 69–101. Zhang, Weiying, Ke, Rongzhu, 2002. Reverse choice in lawsuits and its explanation: an empirical study of written judgments on contract disputes by a grassroots court. Soc. Sci. China 2, 31–43 (in Chinese). Zhou, Li-an, 2004. The incentive and cooperation of government officials in the political tournaments. China Econ. Res. 6, 33–40 (in Chinese).

© Copyright 2026