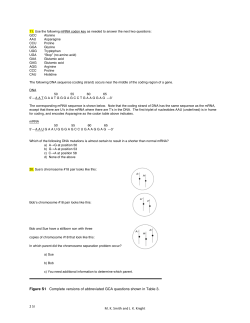

Analysis of microRNA role in the