Ensuring Paid Family Leave Pays Off 2015

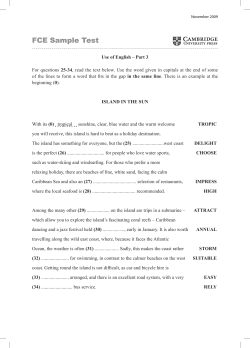

Ensuring Paid Family Leave Pays Off BY Shanna Pearson-Merkowitz, Ph.D. University of Rhode Island Rachel-Lyn Longo, Student Researcher University of Rhode Island 2015 The project was developed as part of The Collaborative’s initiative to engage undergraduate students in research for state leaders. REGIONAL COMPETITIVENESS 2015 REGIONAL COMPETITIVENESS WILL EXPANDING MEDICAID HELP THE ECONOMY? 50 Park Row West, Suite 100 Providence, RI 02903 www.collaborativeri.org Amber Caulkins Program Director [email protected] 401.588.1792 The College & University Research Collaborative (The Collaborative) is a statewide public/private partnership of Rhode Island’s 11 colleges and universities that connects public policy and academic research. The Collaborative’s mission is to increase the use of non-partisan academic research in policy development and to provide an evidence-based foundation for government decision-making. The Collaborative turns research into action by sharing research with policymakers, community leaders, partner organizations, and the citizens of Rhode Island. CURRENT RESEARCH PROJECTS WORKFORCE The Economic Benefits of a Flexible Workplace by Barbara Silver, Ph.D., University of Rhode Island The Knowledge, Skills, and Abilities Needed for Growing Occupations in Rhode Island by Matthew Bodah, Ph.D., University of Rhode Island Preparing Rhode Island’s Workforce for the Jobs of the Future by Elzotbek Rustambekov, Ph.D., Bryant University Shanna Pearson-Merkowitz, Ph.D., is an Associate Professor of Political Science at the University of Rhode Island. She received her Ph.D. in 2009 from the University of Maryland, College Park. Her research focuses on public policy, inequality, and political geography. Professor Pearson-Merkowitz’s research has appeared in some of the top political science journals including the Journal of Politics and the American Journal of Political Science. Rachel-Lyn Longo is a recent graduate of the University of Rhode Island and holds a B.A. in Political Science and Psychology. In the spring of 2014, she studied Paid Family Leave Policies in Rhode Island during a Senior Seminar with Professor Shanna Pearson-Merkowitz. Rachel-Lyn is interested in familial health and wellbeing, which has sparked a curiosity for further research on PFL following the completion of this project. Rhode Island Unemployment: Is There Labor Market Mismatch? by Neil Mehrotra, Ph.D., Brown University INFRASTRUCTURE Improving Infrastructure through Public Private Partnerships by Amine Ghanem, Ph.D., Roger Williams University Millennials on the Move: Attracting Young Workers through Better Transportation by Jonathan Harris, M.I.D., Johnson & Wales University The Road to Better Bridges: Strategies for Maintaining Infrastructure by Nicole Martino, Ph.D., Roger Williams University REGIONAL COMPETITIVENESS Choosing a Health Exchange for Rhode Island by Jessica Mulligan, Ph.D., Providence College The Economic Impact of Expanding Medicaid by Liam Malloy, Ph.D., University of Rhode Island; Shanna Pearson-Merkowitz, Ph.D., University of Rhode Island Ensuring Paid Family Leave Pays Off by Shanna Pearson-Merkowitz, Ph.D., University of Rhode Island Rachel-Lyn Longo, Student Researcher, University of Rhode Island Strategies for a Competitive Rhode Island by Suchandra Basu, Ph.D., Rhode Island College; Ramesh Mohan, Ph.D., Bryant University; Joseph Roberts, Ph.D., Roger Williams University MANUFACTURING Rhode Island’s Maker-Related Assets by Dawn Edmondson, M.S., New England Institute of Technology; Susan Gorelick, Ph.D., New England Institute of Technology; Beth Mosher, MFA, Rhode Island School of Design WILL EXPANDING MEDICAID HELP THE ECONOMY? Ensuring Paid Family Leave Pays Off SHANNA PEARSON-MERKOWITZ, PH.D., UNIVERSITY OF RHODE ISLAND RACHEL-LYN LONGO, STUDENT RESEARCHER, UNIVERSITY OF RHODE ISLAND FIG. 1 MATERNITY/PATERNITY LEAVE GUARANTEED BY LAW 300 Maternity Leave Paternity Leave 250 Days 200 150 100 50 0 Vietnam USA UK Spain Singapore New Zealand Mexico Jamaica Ireland Iran India France Congo China Chad Canada Bangladesh Source: Addati, Cassirer, & Gilchrist (2014) 1 The U.S. is one of the only developed nations that doesn’t guarantee workers paid leave to care for a newborn child or a sick family member. 182 out of 185 countries around the world provide some form of paid maternity leave, and 70 countries also offer paid paternity leave, while the U.S. guarantees neither.1 As a result, just 12% of American workers have access to paid family leave through their job.2 For the rest, taking time off to care for a sick family member or bond with a new child can result in financial hardship, workplace penalties, or even the loss of a job. President Obama recently launched a campaign to expand access to family leave for workers across the country.(a) But a handful of states, including Rhode Island, are already leading the way with their own programs. Paid family leave, known in Rhode Island as Temporary Caregiver Insurance (TCI), ensures people have the capacity to take (a) President Obama is expanding paid parental leave for federal workers and asking Congress for $2 billion to help states create paid family leave programs. He is also pushing for the passage of the Healthy Families Act, which would allow all workers to earn paid sick and family leave time. time off work to care for their family by providing partial replacement for lost wages and, in Rhode Island, guaranteeing their jobs will be available when they return. The Collaborative | March 2015 2 ENSURING PAID FAMILY LEAVE PAYS OFF California was the first state in the U.S. to implement state-sponsored paid family leave in 2002, followed by New Jersey in 2008 and Rhode Island in 2013.(b) How is paid family leave (PFL) working in Rhode Island and other early adopter states, and how might it be improved? Our research evaluates evidence about the effectiveness of state-sponsored paid family leave programs. While studies indicate that PFL has health and financial benefits for families as well as potential economic benefits for states, the data suggest that some workers benefit more than others. Adjusting how benefits are calculated could make PFL more accessible to the low-income families who need it the most and who are most likely to go on public assistance - and thus cost the state tax dollars - without it. PAID FAMILY LEAVE PAYS OFF (b) In 2007, Hawaii also implemented a program to encourage family leave, but it is controlled and funded by employers and participation is optional. (c) The major federal law governing family leave, the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA), was passed by Congress in 1993. The Act enables qualified workers to take unpaid, job-protected leave for up to 12 weeks. However, in addition to the fact that it only provides for job protection, not wage replacement, the wording of the Act has made it inapplicable to many workers. According to one report, only 59% of the workforce qualifies for FMLA.3 (d) Access to paid family leave varies significantly depending on income level. Only 5% of workers with wages in the bottom 25% have access to PFL, compared to 20% of workers with wages in the top 25%.2 3 For the 88% of American workers who don’t have access to paid family leave,(c) taking time off to care for a family member can mean losing their job or facing workplace discipline or sanctions.4 Even for workers who are permitted to take time off, the leave is almost always unpaid.(d) Losing a job or taking unpaid leave from work has both immediate and long-term economic consequences for families. In the short run, households must survive on a drastically diminished budget, a particular problem for those who are barely in the black to begin with. Even if a worker eventually finds a new job, research shows that spells of unemployment significantly decrease future wages.5 Given these challenges, government-sponsored PFL can be a tool to foster security both for families and for the economy as a whole. Research demonstrates that paid family leave pays off for workers and their families. After taking PFL, California families overwhelmingly report experiencing better economic, social, and physical health than those with a new child or sick family member who did not take PFL.6 Receiving care The Collaborative | March 2015 from family members has been shown to drastically improve health outcomes and recovery from illness, especially among children and the elderly.7 Mothers who take paid leave to care for a newborn breastfeed for twice as long, a behavior that has been connected with improved childhood health.6 Paid family leave also improves economic outcomes. A Rutgers University study reports that women who take paid leave after the birth of a child are 93% more likely to have a job nine to twelve months later and 54% more likely to report higher wages one year after giving birth than women who could not take leave.8 For the state, that means more workers paying taxes and contributing to the economy, and fewer people on social welfare programs.(e) New mothers who are able to take PFL are 39% less likely to go on public assistance and 40% less likely to receive food stamps after the birth of their child, compared to mothers who cannot take leave.8 In Rhode Island, objection to the passage of paid family leave legislation came primarily from the ENSURING PAID FAMILY LEAVE PAYS OFF FIG. 3 ACCESS TO FAMILY LEAVE BENEFITS BY FIG. 4 OUTCOMES FOR WOMEN WHO TAKE INCOME BRACKET, 2013 PAID MATERNITY LEAVE 93% 54% 39% 40% Highest 25% Second 25% Third 25% Lowest 25% Percentage of Workers with Access to Benefits PAID UNPAID Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, National Compensation Survey2 more likely to have a job 9 to 12 months after birth more likely to report higher wages one year after birth less likely to go on public assistance after birth less likely to receive food stamps after birth Source: Rutgers University Center for Women and Work8 business community.10 However, research on PFL in California6 and New Jersey11 suggests that employers have generally been happy with the effect of the program. The vast majority of businesses in California reported no negative impact – and in some cases a positive impact – on “productivity, profitability, or performance.”6 Some employers in New Jersey witnessed improved worker morale. Some businesses applaud PFL as a cost-saving measure because it reduces employee turnover, thus saving employers from hiring and training replacement workers.11 STATES LEAD ON MAKING PAID FAMILY LEAVE A REALITY The paid family leave programs in Rhode Island, California, and New Jersey provide between four and six weeks of income replacement at up to two-thirds of a worker’s normal wages.(f) While all three states provide replacement for lost wages, Rhode Island (f) is the only one that provides job protection, requiring that an employee be restored to the same position, status, and benefits after taking PFL. (e) In California and New Jersey, one of the fastestgrowing segments of the population using PFL is people who are caring for an elderly family member.9 Rhode Island has a slightly larger elderly population than the U.S. as a whole, so an increasing number of older workers may use PFL to care for their parents and elderly relatives. PFL may help keep these people in the workforce longer: According to the Employee Benefit Research Institute, one in four retirees reports that they left the workforce early to care for a spouse, parent, or other family member. FIG. 5 PAID FAMILY LEAVE PROGRAMS IN THE UNITED STATES, 2015 STATE Passed Passed in in 2002 2002 Passed Passed in in 2002 2008 Passed Passed in in 2002 2013 ALLOWED LEAVE MAX WEEKLY WAGE REPLACEMENT LEVEL Weeks Weeks Weeks Weeks Weeks Weeks Source: CA Employment Development Dept., NJ Dept. of Labor & Workforce Development, RI Dept. of Labor & Training.12 MAX WEEKLY BENEFIT FUNDING MECHANISM (FOR PFL + TDI COMBINED)* Employee payroll tax of up to 0.9% on taxable income up to $104,378 Employee payroll tax of 0.34% on taxable income up to $32,000 Employee payroll tax of 1.2% of the first $64,200 in taxable income *Note: New Jersey has separate payroll taxes for TDI (0.25%) and PFL (0.09%). They are added together here for comparison purposes. Rhode Island and California have a single tax that funds both programs. The Collaborative | March 2015 4 ENSURING PAID FAMILY LEAVE PAYS OFF (g) Rhode Island has had a Temporary Disability Insurance (TDI) program since 1942. It expanded the program to include PFL in 2013, calling it Temporary Caregiver Insurance (TCI). (h) Based on the current rates, a Rhode Island worker could pay up to a maximum of $14.82 a week in TDI/PFL taxes. (i) Among women in California, who are more likely than men to be primary caregivers and thus to need PFL, 53% earn under $25,000 and 8% earn over $84,000.13 In each of these states, PFL is structured as an extension of Temporary Disability Insurance (TDI), a program that provides short-term wage replacement for people who miss work due to non-workrelated illnesses or injuries.(g) The PFL program expands this coverage to people who miss work because of a family member’s health needs, rather than their own. All three states fund PFL through an employee payroll tax. Funding the program in this way ensures that the beneficiaries (workers) pay for it, rather than placing the burden on employers. While having workers fund the program makes sense, the particular structure of the employee contribution system is, in practice, regressive, in that it places a greater burden on low- and middle-income workers. Like some other programs funded by payroll taxes, such as Social Security, PFL is funded through a fixed tax rate applied to a worker’s taxable earnings up to a specific income level, above which the tax is no longer applied. In Rhode Island, for example, the PFL and TDI programs are funded through a joint 1.2% tax on a worker’s first $64,200 in income.(h) The combination of the flat tax rate and the income cap means low- and middle-income workers end up paying a greater percentage of their earnings to fund the program than high-income workers (see Figure 6). Despite the fact that low-income workers contribute a disproportionate amount of their paychecks to fund the program, they are less likely to utilize PFL than high-income workers. The most recent data from California, where PFL has existed the longest, shows that individuals earning below $24,000 a year account for less than 20% of PFL claims.13 On the other hand, individuals earning over $84,000 a year account for more than 20% of PFL claims, a share that is growing. However, according to the Census’s Current Population Survey for 2013, individuals earning over $84,000 a year make up just over 12% of the population 5 The Collaborative | March 2015 FIG. 6 PERCENT OF SALARY PAID BY WORKERS FOR PFL AND TDI COMBINED 1.20% 1.20% CA NJ .90% .90% RI .67% .55% .34% .22% .08% $19,790 $50,233 The U.S. poverty line for a family of three $140,000 The m edian U.S. The start of the family income top 10% U.S. family income bracket ANNUAL INCOME of California whereas over 40% of workers in the state make less than $25,000 a year.(i) The data suggest that paid family leave is drastically underutilized by those who need it most – the working poor.14 WHY DOES PAID FAMILY LEAVE BENEFIT SOME WORKERS MORE THAN OTHERS? Low-income workers contribute a greater share of their salaries to fund PFL, but may be using the program less than high-income workers. Why? One reason may simply be lack of awareness about the program. Despite overall growth in the utilization of PFL,13,15 more than half of workers in New Jersey15 and California6 were unaware of their state’s PFL program or their eligibility for it. Furthermore, income level was highly correlated with awareness of the program: lower wage workers in California were far less likely to know about the availability of PFL or the fact that they pay into it.6 ENSURING PAID FAMILY LEAVE PAYS OFF FIG. 7 AVERAGE WAGES AND RHODE ISLAND PAID FAMILY LEAVE WAGE REPLACEMENT RATES IN RELATION TO THE POVERTY LINE POVERTY LINE ($380.58/WK) $8 AVERAGE WAGE WAGE REPLACEMENT RATE HOURLY WAGE $10 $15 $20 $25 $30 $35 0 $100 $200 $300 $400 $500 $600 $700 $800 $900 $1000 $1100 $1200 $1300 $1400 WEEKLY INCOME A more troubling problem is that many lowincome workers may be unable to afford to take leave, even when they have access to a state-sponsored partial reimbursement. Existing PFL programs provide less than two-thirds of a worker’s missed wages. As Figure 8 shows, for Rhode Island families already living in poverty, losing a third of their income may simply leave them with too little to make ends meet. The maximum PFL benefit for a full-time, minimum-wage worker in Rhode Island with two children is $192 per week, which is 50% below the poverty line.(j) Most likely, workers like these simply cannot afford to take time off, even with the 60% wage replacement provided by PFL. If taking time off is unavoidable, it might make more sense for a worker to quit their job and apply for state aid than to take PFL. In Rhode Island, only full-time workers earning more than $15.86 per hour receive PFL benefits that put them above the U.S. poverty line (assuming a family of three that includes a single parent and two children). HOW TO ENSURE PAID FAMILY LEAVE BENEFITS ALL WORKERS Most people in the United States cannot take time off work after the birth of a child or to take care of a sick family member without risking their economic security and potentially their job. Rhode Island, California, and New Jersey have led the nation in addressing this issue by passing paid family leave policies that help workers take time off to care for their families. (j) According to the U.S. Census, 13.6% of the state’s population lives below the poverty line. These states can continue to lead the way by ensuring that low-income workers benefit from PFL (which they help pay for), so that it isn’t a program that taxes them more while benefitting them less. As the group most at risk of losing their job or winding up on state assistance without PFL, low-income workers should be a high priority for states trying to protect their economies. There are several measures that could help increase the use of the PFL program among the working The Collaborative | March 2015 6 ENSURING PAID FAMILY LEAVE PAYS OFF poor, and therefore maximize the economic benefits of PFL to the state economy. A statewide education campaign, with a particular focus on low-wage workplaces, could increase utilization by educating workers about the program and their entitlement to benefits. The state could also consider requiring all employers to provide information about PFL to workers. Perhaps more importantly, implementing a more progressive wage replacement system so that lowerincome workers who take PFL receive a higher level of benefits could ensure that no one falls below the poverty line as a result of taking paid family leave. Given that low- and middle-wage workers are those who both need PFL the most and who pay the largest portion of their salary into the program, it is essential that these workers can afford to take advantage of it. Ensuring all workers have access to PFL could also be a smart economic move for the state. It could keep people employed and reduce social service reliance during times of family crisis, and lead to higher earnings, and thus more tax revenue, in the long run. 7 The Collaborative | March 2015 WILL EXPANDING MEDICAID HELP THE ECONOMY? ENSURING PAID FAMILY LEAVE PAYS OFF ENDNOTES 1. Adam Peck and Bryce Covert (2014) “U.S. Paid Family Leave Versus The Rest Of The World, In Two Disturbing Charts,” Think Progress, July 30. Laura Addati, Naomi Cassirer, and Katherine Gilchrist (2014) “Maternity and paternity at work: Law and practice across the world,” Geneva: International Labour Organization. 2. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2013) “National Compensation Survey: Employee Benefits in the United States, March 2013,” Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Labor. 3. National Partnership for Women and Families (2013) “A Look at the U.S. Department of Labor’s 2012 Family and Medical Leave Act Employee and Worksite Surveys,” Washington, DC. 4. Tom W. Smith and Jibum Kim (2010) “Paid Sick Days: Attitudes and Experiences,” Washington, DC: Public Welfare Foundation. In their survey, 11% of people said they had lost a job after taking time off to recover from an illness or care for a sick family member. 5. Daniel Cooper (2014) “The Effect of Unemployment Duration on Future Earnings and Other Outcomes,” working paper no. 13-8, Boston: Federal Reserve Bank of Boston. 6. Eileen Appelbaum and Ruth Milkman (2011) “Leaves that Pay: Employer and Worker Experiences with Paid Family Leave in California,” Washington, DC: Center for Economic and Policy Research. 7. Alison Earle and Jodi Heymann (2006) “A comparative analysis of paid leave for the health needs of workers and their families around the world,” Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis, 8(3): 241-257. 8. Linda Houser and Thomas P. Vartanian (2012) “Pay Matters: The positive economic impacts of paid family leave for families, business, and the public,” New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Center for Women and Work. Linda Houser and Thomas P. Vartanian (2012) “Policy Matters: Public Policy, Paid Leave for New Parents, and Economic Security for U.S. Workers,” New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Center for Women and Work. 9. Lynn Feinberg (2013) “Keeping Up with the Times: Supporting Family Caregivers with Workplace Leave Policies,” Insight on the Issues series, no. 82, Washington, DC: AARP Public Policy Institute. Karen White, Linda Houser, and Elizabeth Nisbet (2013) “Policy in Action: New Jersey’s Family Leave Insurance Program at Age Three,” New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Center for Women and Work. 10. Daniel Da Ponte (2014) Chairman, Rhode Island Senate Committee on Finance, personal interview with Rachel-Lyn Longo, April 9. 11. Sharon Learner & Eileen Appelbaum (2014) “Business As Usual: New Jersey Employer’s Experiences with Family Leave Insurance” Washington, DC: Center for Economic and Policy Research. 12. California Employment Development Department (2015) “2015 California Employer’s Guide,” DE 44 Rev. 41 (1-15), Sacramento, CA: State of California, Labor and Workforce Development Agency. New Jersey Department of Labor and Workforce Development (2015) “Family Leave Insurance Benefits - General Information,” Trenton, NJ [website accessed January 9, 2015]. Rhode Island Department of Labor & Training (2015) “Temporary Disability Insurance / Temporary Caregiver Insurance,” Cranston, RI [website accessed January 9, 2015]. 13. Brie Lindsey and Daphne Hunt (2014) “California’s Paid Family Leave Program: Ten Years After The Program’s Implementation,” Sacramento, CA: California Senate Office of Research. 14. It is important to note that not all workers earning less than $25,000 a year are eligible for PFL. If they work intermittently or not at all, they may not have any income during the period on which benefit calculations are based. As a result, it is difficult to calculate the exact percentage of the public who make under $25,000 and qualify for the program. 15. State of New Jersey Department of Labor and Workforce Development (2014) Family Leave Program Statistics, 2009-2014 [data files]. The Collaborative | March 2015 8 The Collaborative was developed in response to calls from the Governor’s office, public officials, and community leaders to leverage the research capacity of the state’s 11 colleges and universities and to provide non-partisan research for informed economic policy decisions. 50 Park Row West, Suite 100 Providence, RI 02903 www.collaborativeri.org Amber Caulkins Program Director [email protected] 401.588.1792 Following the Make It Happen RI economic development summit, the Rhode Island Foundation committed funding for the creation of The Collaborative. As a proactive community and philanthropic leader, the Foundation recognized The Collaborative as an opportunity for public and private sectors to work together to improve the quality of life for all Rhode Island residents. In FY 2013, the State of Rhode Island matched the Foundation’s funding, viewing The Collaborative as a cost-effective approach to leverage the talent and resources in the state for the development of sustainable economic policy. Rhode Island’s 11 colleges and universities agreed to partner with The Collaborative, and the presidents from each institution formed the Leadership Team. A Panel of Policy Leaders was appointed by the Governor’s office, the Rhode Island House of Representatives, and the Rhode Island Senate to represent both the executive branch and the legislative branch of state government. This panel is responsible for coming to consensus on research areas of importance to Rhode Island. PARTNERS Footnote is an online media outlet that expands the reach of academic expertise by translating it into accessible, engaging content for targeted audiences. It offers readers concise, compelling articles that highlight influential thought leadership from top colleges and universities. Footnote editors Diana Brazzell and Rachel Bloom collaborated with the researchers on the writing and editing of this brief. www.footnote1.com Nami Studios is a creative services consultancy, offering strategic design for marketing, data visualization for communications, and interactive user experiences. Through our partnership with Nami Studios, we enhance our articles with enlightening and interactive visualizations of the research data. ADMINISTERED BY FUNDED BY The Association of Independent Colleges and Universities of Rhode Island is an alliance representing the eight independent institutions of higher learning within the State of Rhode Island. Designed to address common interests and concerns of independent colleges and universities within the state, the Association serves as the collective and unified voice of its member institutions. For questions and more information about The Collaborative, please visit collaborativeri.org 2015 REGIONAL COMPETITIVENESS 2015 REGIONAL COMPETITIVENESS

© Copyright 2026