The Road to Better Bridges: Strategies for Maintaining Infrastructure

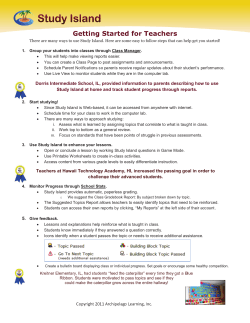

The Road to Better Bridges: Strategies for Maintaining Infrastructure BY Nicole Martino, Ph.D. Roger Williams University 2015 INFRASTRUCTURE 2015 REGIONAL COMPETITIVENESS WILL EXPANDING MEDICAID HELP THE ECONOMY? 50 Park Row West, Suite 100 Providence, RI 02903 www.collaborativeri.org Amber Caulkins Program Director [email protected] 401.588.1792 The College & University Research Collaborative (The Collaborative) is a statewide public/private partnership of Rhode Island’s 11 colleges and universities that connects public policy and academic research. The Collaborative’s mission is to increase the use of non-partisan academic research in policy development and to provide an evidence-based foundation for government decision-making. The Collaborative turns research into action by sharing research with policymakers, community leaders, partner organizations, and the citizens of Rhode Island. CURRENT RESEARCH PROJECTS WORKFORCE The Economic Benefits of a Flexible Workplace by Barbara Silver, Ph.D., University of Rhode Island The Knowledge, Skills, and Abilities Needed for Growing Occupations in Rhode Island by Matthew Bodah, Ph.D., University of Rhode Island Nicole Martino, Ph.D., is an Assistant Professor of Engineering in the School of Engineering, Computing and Construction Management at Roger Williams University. She earned her Ph.D. in Civil and Environmental Engineering from Northeastern University. Her academic areas of specialty include structural analysis and design of concrete and steel structures. Her research interests focus on the ability to understand the various stages of reinforced concrete bridge deck deterioration using electromagnetic, electrochemical, and mechanical nondestructive evaluation techniques, and has presented and published many papers in this topic area. The ultimate goal of her research is to develop a tool, user friendly to transportation agencies, that can immediately and accurately assess the internal composition of bridge decks. Preparing Rhode Island’s Workforce for the Jobs of the Future by Elzotbek Rustambekov, Ph.D., Bryant University Rhode Island Unemployment: Is There Labor Market Mismatch? by Neil Mehrotra, Ph.D., Brown University INFRASTRUCTURE Improving Infrastructure through Public Private Partnerships by Amine Ghanem, Ph.D., Roger Williams University Millennials on the Move: Attracting Young Workers through Better Transportation by Jonathan Harris, M.I.D., Johnson & Wales University The Road to Better Bridges: Strategies for Maintaining Infrastructure by Nicole Martino, Ph.D., Roger Williams University REGIONAL COMPETITIVENESS Choosing a Health Exchange for Rhode Island by Jessica Mulligan, Ph.D., Providence College The Economic Impact of Expanding Medicaid by Liam Malloy, Ph.D., University of Rhode Island; Shanna Pearson-Merkowitz, Ph.D., University of Rhode Island Ensuring Paid Family Leave Pays Off by Shanna Pearson-Merkowitz, Ph.D., University of Rhode Island Rachel-Lyn Longo, Student Researcher, University of Rhode Island Strategies for a Competitive Rhode Island by Suchandra Basu, Ph.D., Rhode Island College; Ramesh Mohan, Ph.D., Bryant University; Joseph Roberts, Ph.D., Roger Williams University MANUFACTURING Rhode Island’s Maker-Related Assets by Dawn Edmondson, M.S., New England Institute of Technology; Susan Gorelick, Ph.D., New England Institute of Technology; Beth Mosher, MFA, Rhode Island School of Design WILL EXPANDING MEDICAID HELP THE ECONOMY? The Road to Better Bridges: Strategies for Maintaining Infrastructure NICOLE MARTINO, PH.D., ROGER WILLIAMS UNIVERSITY A considerable number of Rhode Island’s 765 highway bridges FIG. 1 CONDITION OF RI BRIDGES are in need of repair.(a) According to the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), the condition of the state’s bridges is the worst in the nation.1 More than one in five bridges are FUNCTIONALLY OBSOLETE 56.5% classified as structurally deficient and therefore in need of “significant maintenance, rehabilitation, or replacement.”2 STRUCTURALLY Many Rhode Island residents are well aware of these conditions as they make their daily commutes, drive to the store, or pick up their children from school. What they may not know is that potholes and bumpy roads are more than just an inconvenience: these unpleasant road conditions increase DEFICIENT Source: American Society of Civil Engineers 2 (a) Highway bridges are bridges that span more than 20 feet. vehicular maintenance costs, compromise safety, and hamper economic growth. Percentage of Bridges FIG. 2 PERCENTAGE OF BRIDGES THAT ARE STRUCTURALLY DEFICIENT OR FUNCTIONALLY OBSOLETE Source: American Society of Civil Engineers 2 The Collaborative | March 2015 2 THE ROAD TO BETTER BRIDGES: STRATEGIES FOR MAINTAINING INFRASTRUCTURE The American Society of Civil Engineers estimates that driving on roads in poor condition costs an extra $444 per driver in annual vehicle repair and operation costs.3 By stymieing transportation, poor infrastructure is also responsible for lost jobs, diminished exports, and a reduced standard of living.4 In Rhode Island, for example, businesses and commercial industry that require ground transportation of heavy freight have felt this impact as they have had to reroute delivery trucks due to reduced allowed weight on bridges in key locations along I-95. Altogether, in 2010, deficient bridges and roads were estimated to cost the U.S. $10 billion annually, and that figure is expected to rise to $58 billion by 2020.4 FIG. 3 THE COST AND IMPACT OF POOR INFRASTRUCTURE 38hrs Each year, commuters spend an average of 38 hours stuck in traffic. 444 $ Roads needing repair cost American drivers $94B per year. That’s $444 per motorist! 1060 $ The average American family will spend over $1,060 each year through 2020 because of declining transportation infrastructure according to the ASCE. ECONOMIC IMPACT OF FAILING U.S. TRANSPORATION INFRASTRUCTURE BY 2020 877K America would lose 877,000 jobs Source: American Society of Civil Engineers3 3 The Collaborative | March 2015 28B $ U.S. exports would drop by $28 billion THE ROAD TO BETTER BRIDGES: STRATEGIES FOR MAINTAINING INFRASTRUCTURE FIG. 4 STATE TRANSPORTATION OFFICIALS INTERVIEWED (b) States were chosen for the survey based on having a low percentage of their bridges (between 3% and 9% compared to 23% in Rhode Island) ranked as structurally deficient by FHWA in 2014.1 The first four states were chosen because they, like Rhode Island, have to deal with significant snowfall every year. Arizona has little snow but does have one of the lowest rates of structurally deficient bridges in the country. Repairing bridges and keeping them in good condition requires funding and resources. How can Rhode Island improve its bridge infrastructure in an efficient and cost-effective way? One approach is to learn from the practices of states whose bridges are ranked among the best in the nation by the FHWA. This article presents results from a telephone survey conducted with transportation officials from bridge inspection and management divisions in five of those states – Utah, Wisconsin, Montana, Illinois, and Arizona – as well as officials in Rhode Island.(b) The officials were asked about bridge inspection techniques, data management and analysis approaches, maintenance and preservation practices, and funding mechanisms. Lessons from these surveys may help Rhode Island improve its bridge inspection, classification, and maintenance practices.(c) IMPROVING INSPECTION PRACTICES Regular, thorough inspections are necessary to determine the condition of bridges and identify those in need of repair. All states, including Rhode Island, must follow the minimum inspection practices required by the FHWA, one of them being that visual inspections have to be conducted every two years. Inspectors look for signs of deterioration like cracking and spalling, in which potholes form due to crumbling concrete or asphalt. The inspectors then rate each bridge element according to FHWA’s National Bridge Inspection Standards (NBIS),5 sometimes supplemented with additional state standards.(d) (c) A total of five officials from outside Rhode Island were interviewed, one in each state. The officials were from bridge management agencies within the state departments of transportation, and their titles ranged from Chief Bridge Maintenance Engineer to Bureau Chief to Project Manager. (d) Rhode Island’s bridge inspection manual6 draws on the Manual for Bridge Evaluation from the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO) for guidance on federal standards.7 It also draws from Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Pennsylvania state standards. The Collaborative | March 2015 4 THE ROAD TO BETTER BRIDGES: STRATEGIES FOR MAINTAINING INFRASTRUCTURE Inspection teams are managed by engineers who meet FHWA qualifications regarding education, training, and experience in bridge inspection.5 In Rhode Island, inspectors are often outside consultants who specialize in evaluating and rating bridges. While visual inspections are helpful, they can only identify damage that is obvious on the surface of a bridge, especially the deck (the bridge roadway). My survey of states with high-quality bridge infrastructure found that they often incorporate more advanced techniques into their bridge inspection practices, and are developing plans to bring these techniques into their regular, biannual inspections. The techniques, including ground penetrating radar, impact echo, ultrasonic methods, and infrared thermography, can determine if there is damage inside the deck and even estimate how severe that damage may be.8 Damage usually develops in the subsurface of a structure long before it becomes apparent on the outer surface of the bridge deck. Finding this damage before it is visible and repairing it at an early stage can save money and promote public safety. In addition to using more advanced inspection techniques, states with bridges in good condition also implement rigorous quality control procedures to ensure that their bridges are properly inspected. For example, Utah hosts a collaborative review once per year, wherein each of its in-house inspectors reviews the same bridge. All of their inspection reports are compared and analyzed for discrepancies, so procedural improvements for the next year of inspections can be appropriately developed and implemented. Other quality control measures used by states include auditing 1% of inspection reports, independently reviewing 3% of inspections, and having inspectors review different bridges from year to year. These measures also serve as a form of training for bridge inspectors, providing feedback on their inspection techniques and decision making. Thus, states with more rigorous quality control procedures may end up with more experienced, well-trained inspectors. CLASSIFYING BRIDGES & PRIORITIZING REPAIRS Information gleaned from bridge inspections must be organized and analyzed in order to accurately classify the condition of a state’s bridges. The results of the analysis are used to determine which bridges need repair, what kinds of repairs are necessary, and how urgently the repairs are needed.9 Many states, including Rhode Island, log their inspection data into a data management program called AASHTOWare Bridge Management (formerly known as PONTIS), which will also incorporate a data analysis component in the future. However, four out of the five high-performing states I surveyed have their own custom databases and/or repair prioritization systems that they developed in-house. 5 The Collaborative | March 2015 Prioritization systems classify bridges in a variety of ways, but categories are typically based on the NBIS rating of the structure’s current condition and the length of time the bridge has maintained that rating. Bridge classification also factors in the return on investment of any potential repairs, which is an estimate of how long the repairs would extend the bridge’s service life and how much money they would save as a result, balanced against the estimated cost of the repairs. Based on these classification factors, decisions are made about if, when, and how different bridges should be repaired. THE ROAD TO BETTER BRIDGES: STRATEGIES FOR MAINTAINING INFRASTRUCTURE The high-performing states I surveyed have innovative methods for organizing and prioritizing repairs based on the status of their bridges. In order to use repair funding in the most efficient way possible, some states bundle similar projects to save money. For example, if multiple bridge decks need to have their overlay (the asphalt or concrete surface) replaced, the state may pay one company to do them all at once, instead of repairing one deck and then going through the whole process again for another deck the following year. By acting early, states can also opt to select a contractor based on who will make the repairs at the lowest cost, rather than in the quickest time. PROMOTING PREVENTIVE MAINTENANCE While it is natural to focus on the bridges that are in the worst shape, preventive maintenance of bridges at all levels can be much more cost-effective than waiting until a bridge needs major repairs or even replacement.10 The proper maintenance of bridges can also extend their service life, meaning that the scheduled replacement date the structure was designed for can be pushed back for up to 25 years. With this in mind, some of the states I surveyed require biannual cleaning of any drains and joints in the bridge structure, sealing of cracks, and sweeping, washing, and sealing the deck. These forms of maintenance help keep the bridge deck and structure in good condition and prevent certain types of damage. Funding for bridge maintenance has traditionally come from car registration fees and gas taxes. Al- though these are the primary funding sources for maintenance in Rhode Island, according to officials, the state currently only earmarks 1 out of every 17 cents from these sources for maintenance – the rest goes to the general fund. In contrast, most states I surveyed channel most or all of the money raised from registration fees and gas taxes specifically for maintenance. However, preventive maintenance has become a higher priority in Rhode Island, as the state recently invested $5 million in bridge maintenance and repairs along the I-95 corridor, and is looking into ways to ensure maintenance funds are spent effectively.11 FIG. 5 HOW REVENUE FROM CAR REGISTRATION FEES AND GAS TAXES IS SPENT IN RHODE ISLAND General Fund Maintenance The Collaborative | March 2015 6 THE ROAD TO BETTER BRIDGES: STRATEGIES FOR MAINTAINING INFRASTRUCTURE INVESTING IN THE FUTURE OF RHODE ISLAND’S BRIDGES (e) While federal funding is still not available for many types of general maintenance, such as deck sweeping and drain cleaning, other specific preventive maintenance measures are eligible for funding. For example, funding can be used to repair deteriorated areas within the deck before the damage advances to a point where it is visible on the outer surface. Given the current condition of many roads and bridges in the U.S., the national focus is beginning to shift towards preventive maintenance and repair. Historically, because federal funding was only available for major repairs or replacements, some states did little in the way of preventive maintenance – it was more cost-effective to simply let bridges deteriorate until they became eligible to be replaced using federal funds. However, 2012 changes to highway funding policies, known as MAP-21, now permit states to request federal funding for certain types of bridge preservation measures.12 In response, states are developing their own bridge preservation and maintenance policies and are implementing research projects with the underlying goal of slowing bridge deck deterioration.(e) The bridge infrastructure throughout the state of Rhode Island is in poor condition and will continue to worsen if preventive measures are not taken. Summarized below are the tactics used by the states I surveyed to keep their bridge structures in an acceptable condition: Advanced inspection technologies that can detect damage early Quality control measures to ensure the accuracy of inspections and serve as additional training for inspectors Advanced systems for managing and organizing inspection data Innovative approaches to prioritizing repairs Preventive maintenance measures to extend bridge life span 7 The Collaborative | March 2015 THE ROAD TO BETTER BRIDGES: STRATEGIES FOR MAINTAINING INFRASTRUCTURE Approaches like these can not only improve the condition of bridge infrastructure, making driving safer and more pleasurable, but can also save money in the long run. Through system-wide innovation, Rhode Island has the potential to one day become a national leader in the area of bridge infrastructure. The Collaborative | March 2015 8 WILL EXPANDING MEDICAID HELP THE ECONOMY? ENDNOTES 1. Federal Highway Administration (2014) Deficient Bridges by State and Highway System, 1992-2014 [data files], Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Transportation. 2. American Society of Civil Engineers (2013) “2013 Report Card for America’s Infrastructure: Rhode Island,” Reston, VA. 3. American Society of Civil Engineers (2015) “Fix the Trust Fund,” Reston, VA [website accessed Feb. 11, 2015]. 4. Economic Development Research Group (2011) “Failure to Act: The Economic Impact of Current Investment Trends in Surface Transportation Infrastructure,” Washington, D.C.: American Society of Civil Engineers. 5. Federal Highway Administration (2012) “Bridge Inspector’s Reference Manual,” Pub. FHWA NHI 12-049, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Transportation. 6. Rhode Island Department of Transportation (2013) “Bridge Inspection Manual,” Providence, RI. 7. American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (2011) “Manual for Bridge Evaluation,” 2nd edition, Washington, D.C. 8. Nenad Gucunski, Arezoo Imani, Francisco Romero, Soheil Nazarian, Deren Yuan, Herbert Wiggenhauser, Parisa Shokouhi, Alexander Taffe, and Doria Kutrubes (2013) “Nondestructive Testing to Identify Concrete Bridge Deck Deterioration,” Washington, D.C.: Transportation Research Board. 9. For more on how bridges are classified and repairs are prioritized, see: Michael Markow and William Albert Hyman (2009) “Bridge Management Systems for Transportation Agency Decision Making: A Synthesis of Practice,” Washington, D.C.: Transportation Research Board. 10. Federal Highway Administration (2011) “Bridge Preservation Guide,” Pub. FHWA-HIF-11042, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Transportation. 11. Rhode Island Department of Transportation (2013) “Governor Chafee, RIDOT Announce Beginning of Bridge Preservation Program [press release],” Providence, RI, April 5. 12. Federal Highway Administration (2012) “Moving Ahead for Progress in the 21st Century Act (MAP-21): A Summary of Highway Provisions,” Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Transportation. The Collaborative was developed in response to calls from the Governor’s office, public officials, and community leaders to leverage the research capacity of the state’s 11 colleges and universities and to provide nonpartisan research for informed economic policy decisions. 50 Park Row West, Suite 100 Providence, RI 02903 www.collaborativeri.org Amber Caulkins Program Director [email protected] 401.588.1792 Following the Make It Happen RI economic development summit, the Rhode Island Foundation committed funding for the creation of The Collaborative. As a proactive community and philanthropic leader, the Foundation recognized The Collaborative as an opportunity for public and private sectors to work together to improve the quality of life for all Rhode Island residents. In FY 2013, the State of Rhode Island matched the Foundation’s funding, viewing The Collaborative as a cost-effective approach to leverage the talent and resources in the state for the development of sustainable economic policy. Rhode Island’s 11 colleges and universities agreed to partner with The Collaborative, and the presidents from each institution formed the Leadership Team. A Panel of Policy Leaders was appointed by the Governor’s office, the Rhode Island House of Representatives, and the Rhode Island Senate to represent both the executive branch and the legislative branch of state government. This panel is responsible for coming to consensus on research areas of importance to Rhode Island. PARTNERS Footnote is an online media outlet that expands the reach of academic expertise by translating it into accessible, engaging content for targeted audiences. It offers readers concise, compelling articles that highlight influential thought leadership from top colleges and universities. Footnote editors Diana Brazzell and Diana Gitig collaborated with the researcher on the writing and editing of this brief. Nami Studios is a creative services consultancy, offering strategic design for marketing, data visualization for communications, and interactive user experiences. Through our partnership with Nami Studios, we enhance our articles with enlightening and interactive visualizations of the research data. ADMINISTERED BY FUNDED BY The Association of Independent Colleges and Universities of Rhode Island is an alliance representing the eight independent institutions of higher learning within the State of Rhode Island. Designed to address common interests and concerns of independent colleges and universities within the state, the Association serves as the collective and unified voice of its member institutions. For questions and more information about The Collaborative, please visit collaborativeri.org 2015 INFRASTRUCTURE 2015 REGIONAL COMPETITIVENESS

© Copyright 2026