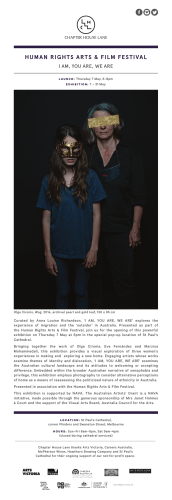

Part 4 - Competition Policy Review Final Report