big game hunting in portugal: present and future perspectives

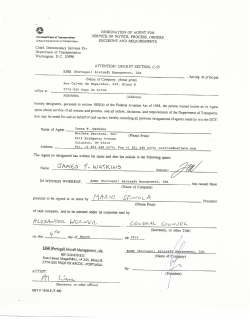

27 BIG GAME HUNTING IN PORTUGAL: PRESENT AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES C. Fonseca Department of Biology & CESAM, University of Aveiro, Aveiro, Portugal, [email protected] In Portugal, five ungulate species are considered as big game: wild boar (Sus scrofa), red deer (Cervus elaphus), roe deer (Capreolus capreolus), fallow deer (Dama dama) and mouflonor wild sheep (Ovis amon). The wild boar is the most important big game species in terms of distribution and hunted animals per year (Fonseca & Correia, 2008). Official records indicated around 15,400 thousands wild boars legally killed during the 2008/2009 hunting season (Fig. 1). However the situation was very different 50 years ago. In 1967 wild boar was consider a non-hunting species in Portugal and its hunting was forbidden outside fenced areas. This circumstances, associated to the gradual abandon of the agriculture fields and consequent increase of the scrubland and forest areas, as well as to the high prolificacy of the species (Fonseca et al. 2011) permit a rapid increase of the species in Portugal, originated from some core populations located in the mountainous regions of the north, centre and south of the country (Ferreira et al, 2009).Currently the wild boar is distributed all over the country with the exception of few littoral areas near the Atlantic Ocean and in the big metropolitan areas (mainly Oporto and Lisbon). The red deer is the biggest native Iberian cervid. Presently it occupies several border regions between Portugal and Spain, where we can find the most important natural populations, originated by animals dispersing from the Spanish territory. The Portuguese red deer populations from Montesinho, TejoInternacional and Alentejo Interior (Contenda-Barrancos) result, mainly, by the expansion of the Spanish populations (Vingada et al. 2010). However, other red deer populations such as Lousã and Monchique (Algarve) mountains result from reintroductions conducted during the end of the last century (Fonseca 2004).Nowadays the hunting of red deer in Portugal occurs in natural populations (indicated above) and in fenced areas (mostly in the south of the country). Around 4,000 thousand red deer were killed in the last hunting season. Fallow deer wasintroduced in Portugal several centuries ago. Its present distribution area is very restricted and frequentlyconfined to enclosures. The most important fallow deer population occurs in the TapadaNacional de Mafra, an 819 ha enclosure where the species is sympatric with red deer and wild boar (Vingada et al. 2010). Several semi-captivity populations exist in the south and centre of Portugal. Although several animals have already escaped from these fenced areas, the free-ranging populations are located in the Sadoriverand Évoraregions. Portuguese hunters do not consider fallow deer an attractive game species. In the 2008/2009 hunting season, 452 fallow deer were legally hunted in Portugal, especially trophy hunting. Roe deer is considered a native species occurring mostly in the North and Centre of Portugal. In the north of Douro river the populations are considered natural (Torres et al. 2011), existing there for centuries and having a strong link with the Spanish ones (Galicia and Castilla Leon), while in the south of this river roe deer populations are the result of relatively recent reintroduction processes (Carvalho et al. 2008) for hunting and conservation purposes, namely for the conservation of the Iberian wolf population in the areas located in the south of Douro river (Arada and Malcata mountains). Roe deer legal hunting in Portugal practically does not exist. One or two hunting units are allowed to kill this cervid under tight rules. Mouflon is classified as an exotic species in Portugal. It was legally introduced exclusively for game purposes in 1990. At the moment, the mouflonoccurs in some hunting fenced areas in Alentejo and TejoInternacional (south and centre interior of Portugal). Around 100 individuals were shot in the hunting season 2008/2009. The big game hunting in Portugal is widely legislated. Among several specificities, the big game methods are a) “By stalking” (Aproximação)–when the hunter actively searches, pursues and capture game with or without the help of hunting dogs and a game guide;b) Sit and Wait hunting (Espera)– when the hunter remains in oneplace, usually high seat or observation platform; c) Battue hunting (Batida)- the hunter waits for game driven by beaters without hunting dogs;d) Drive hunting (Montaria), the most common one – when the hunter waits, in a previously designated location, for large game disturbed by dog packs driven by beaters and f) “Spear hunting” (Cavalo com lança)–when the hunter uses a spear to kill game with or without a horse or hunting dogs. Besides the historical, social and economic relevance of the hunting, currently the management of big game in Portugal is facing new challenges. The stakeholders are aware that the correct management should be based on field data collected, treated and presented by technicians and wildlife researchers, who necessarily should implement policies, decisions and management actions. REFERENCES Carvalho, P., Nogueira, A., Soares, AMVM and Fonseca, C. (2008). Ranging behaviour of translocated roe deer in a Mediterranean habitat: seasonal and altitudinal influences on home range size and patterns of range use. Mammalia. 72: 89-94. Ferreira E., Souto L., Soares A.M.V.M. & Fonseca C. (2009). Genetic structure of the wild boar population in Portugal: Evidence of a recent bottleneck. Mammalian Biology 74 (4): 274-285. Fonseca, C. (2004). Berrosna Serra (O regresso dos veados à Serra da Lousã) [The return of the red deer to Lousa Mountain]. NationalGeographic Magazine - Portugal. N.º 38 (Maio 2004): 11 – 21. [In Portuguese]. Fonseca, C. & Correia, F. (2008). O Javali [The Wild Boar]. Colecção Património Natural Transmontano. João Azevedo Editor (1.ª Edição). Mirandela, 168 pp. [In Portuguese]. Fonseca C., A. Alves da Silva, J. Alves, J. Vingada and A.M.V.M. Soares (2011). Reproductive performance of wild boar females in Portugal.European Journal of Wildlife Research. 57 (2): 363–371. 28 Torres R.T., Santos J., Linnell J.D.C., Virgós E., Fonseca C. (2011). Factors affecting roe deer occurrence in a Mediterranean landscape, Northeastern Portugal. Mammalian Biology 76 (4): 491-497. Vingada, J., Fonseca, C., Cancela, J., Ferreira, J. and Eira, C. (2010) Ungulates and their Management in Portugal.Pp: 392-418. In: Apollonio, M., Andersen, R. & Putman, R.J. (eds.) European Ungulates and their Management in the 21st Century. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge. Fig. Wild boars legally hunted in Portugal from 1989 until 2009.

© Copyright 2026