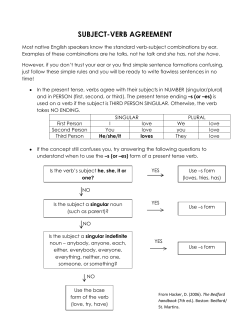

A Learning Dovahzul The Unofficial Guide to the Dragon Language of Skyrim