Differences in corporate saving rates in China: Ownership

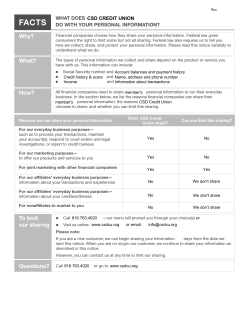

China Economic Review 33 (2015) 25–34 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect China Economic Review Differences in corporate saving rates in China: Ownership, monopoly, and financial development Shiqing XIE ⁎, Taiping MO Department of Finance, School of Economics, Peking University, 100871 Beijing, PR China a r t i c l e i n f o Article history: Received 6 July 2014 Received in revised form 11 January 2015 Accepted 11 January 2015 Available online 15 January 2015 JEL classification: G32 O16 Keywords: Corporate saving rates Ownership Financial development Financing constraints a b s t r a c t Using the data of the listed non-financial companies from 2003 to 2012, this paper conducts a firm-level empirical analysis to reveal the determinants that lead to differences in saving rates of different enterprises in China. Particularly, we explore the discrepancies in the Chinese enterprises' saving rates from the new perspectives of ownership type, monopoly status, and financial development. We find that only some financial indicators of a firm, including the size and the long-term solvency ability, have direct impact on its saving rate. Besides, the difference in the saving rates between private firms and state-owned firms is insignificant while monopolies have higher saving rates than non-monopolies. Most importantly, financial development generally reduces a firm's saving rate and the impact is independent on its ownership type and monopoly status. Moreover, financial development decreases the influence of a firm's short-term solvency and profitability on its saving rate. © 2015 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 1. Introduction It has long been remarked upon that China's national saving rate is extraordinarily high. As the investment and export are both high due to the abundance of domestic saving, the high saving rate has been regarded as the main driving force of China's rapid economic growth. However, despite its contribution to China's economy miracle, the high national saving rate is now more taken as a structural problem of the Chinese economy. On the one hand, the share of consumption in GDP is consistently low due to the high and rising aggregate saving, which dampens the sustainability of China's economy growth in the long run. On the other hand, the high proportion of net export in GDP leaves the economy especially susceptible to the demand shock of the global market. Besides, the huge current account surplus due to the high net export nearly deprives the Peoples' Bank of China of its monetary policy independency. In reality, not only is the high national saving rate perceived to be the cause of domestic economic imbalances in China, it is also believed to be responsible for the global trade imbalances and even the 2008 global financial crisis (Bayoumi, Tong, & Wei, 2010). Because of the abovementioned concerns, the Chinese national saving rate has received wide attention from scholars. However, so far the focus has been mainly on household saving rates (e.g., Horioka & Wan, 2007; Kraay, 2000; Wei & Zhang, 2009). A popular and easy-to-understand perspective is that Chinese people tend to save more than their peers in other countries due to a cultural tradition of thrift. Nevertheless, other evidence (e.g., He & Cao, 2007; Ma & Yi, 2010) shows that the high national saving rate is largely attributed to high government and corporate savings rather than household savings. In fact, increases in corporate saving and government ⁎ Corresponding author. Tel.: +86 10 6275 7260. E-mail addresses: [email protected] (S. Xie), [email protected] (T. Mo). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2015.01.007 1043-951X/© 2015 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 26 S. Xie, T. Mo / China Economic Review 33 (2015) 25–34 saving, as opposed to household saving, have been shown to directly promote overall national saving, as well as affecting the actual structure of saving and investment (Kuijs, 2005). Existing studies on the factors that have led to a high corporate saving rate in China are relatively rare. Xu, Zhou, and Zhao (2011) believe large disparity in income distribution is one reason. They also highlight that decreased spending resulting from low interest rates and low dividends, together with the existence of a “resource rent” caused by resource price distortions, contribute to high corporate saving rates. Huang (2011) compares private enterprises to state-owned enterprises and finds a precautionary savings motive for the private enterprises to have higher saving rates, which is primarily due to their severe financing constraints and better investment opportunities. Overall, it seems that there is no consensus on the causes of high corporate savings. Therefore, instead of directly uncovering the factors that lead to the high corporate saving rates in China, in this paper we aim to reveal the determinants that lead to differences in saving rates of different enterprises in China, specifically by explaining the discrepancies in the Chinese enterprises' saving rates from the new perspectives of ownership type, monopoly status, and financial development. We believe that an investigation from these perspectives is imperative in the sense that understanding the differences within the Chinese companies can also provide helpful solvencies for the Chinese saving puzzle. Using the data of the non-financial companies listed on the Shanghai and Shenzhen Stock Exchanges from 2003 to 2012, we find that a firm's specific financial situation, including its size level and its long-term solvency, has impacts on its saving decisions. Besides, the firms' saving rates also vary with their monopoly status. In addition, financial development generally reduces the saving rates of all types of firms, and it reduces the influence of a firm's short-term solvency and profitability on its saving rate. The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the historical trends of the national saving and the savings in the three respective sectors. Section 3 discusses the factors that may affect corporate saving and the impact of financial development on corporate saving. Section 4 introduces the empirical methods and the data utilized in this paper. Section 5 presents the empirical results and Section 6 concludes. 2. The Chinese saving puzzle National saving in China is quite high both looking from its own historical trends and comparing to other countries. This fact is widely recognized by many scholars such as Kuijs (2005), He and Cao (2007), and Yang, Zhang, and Zhou (2011). In 1992, the national saving rate in China was merely 36.29%. It surged to 51.91% in 2008, reaching its highest level of the recent decades. Besides, Yang et al. (2011) show that the national saving in China is higher than both the comparable developing peers and main developed countries. Revealing the driving forces of the increase in national saving in China necessitates the comparison of the three main components of national saving, including household saving, corporate saving, and government saving. Using the data from the Flow of Funds Accounts (FFA), we are able to illustrate how the savings in the three sectors have contributed to the upward trend of the national saving. FFA was firstly published in 1995 by the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) in China, based on the physical transitions of the national income accounting in the Statistical Yearbook of China. The latest FFA is updated to 2011. Table 1 shows the saving rates of the corporate, government, and household sector respectively from 1992 to 2011, where the saving rate is measured as the ratio of each sector's saving over the gross national dispensable income. Evidently, national saving rate in China remains at a high level and even increases from 36.29% in 1992 to 50.63% in 2011. The rise of saving rate in each sector is more illustrative. The saving rates in the sectors of corporate, government, and household increase by 8.33%, 1.36%, and 4.65% Table 1 Components of national saving as percentage of national dispensable income.Source: NBS, Chinese Statistical Yearbook 1995–2013. Year Corporate (%) Government (%) Household (%) Total (%) 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 11.70 15.73 14.53 16.22 13.69 13.10 13.45 14.70 17.94 18.92 19.34 19.94 22.51 21.60 21.54 22.10 22.74 21.19 21.19 20.03 4.39 4.12 3.17 2.57 3.71 4.01 3.31 2.67 −1.37 −1.08 0.62 1.40 2.59 3.33 4.22 5.68 5.89 4.94 5.16 5.75 20.19 18.16 21.67 19.89 20.15 21.56 21.37 20.04 20.99 20.62 20.28 21.71 20.63 21.53 22.39 23.11 23.28 24.44 25.43 24.85 36.29 38.01 39.36 38.68 37.54 38.66 38.13 37.41 37.56 38.46 40.24 43.05 45.74 46.46 48.15 50.89 51.91 50.57 51.77 50.63 S. Xie, T. Mo / China Economic Review 33 (2015) 25–34 27 respectively, which indicates that corporate saving is the main driving force of the increasing national saving in China. Indeed, the corporate saving nearly explains two thirds of the increase in the national saving rate. The preliminary statistics in our analysis confirm the idea that national saving rate has increased a lot during the last two decades. More importantly, our results show that corporate saving rather than household saving contributes most to the rise of national saving rate. Therefore, an exploration of the corporate saving can facilitate a better understanding of why the national saving rate is so high and why it has increased so much. 3. Theoretical background 3.1. Corporate saving rates For individual companies, corporate saving is a firm's retained earnings, which is equal to the difference between a firm's net profit and the dividend payout. For the whole business sector, gross savings equal the sum of all savings by individual companies. Despite the similarities between the two definitions, the objectives of studies on corporate sector saving rates are slightly different from studies on saving by individual enterprises. When looking at a whole sector, attention should be paid to both the proportion of that sector's net profit in gross national disposable income and the way net profit within a sector is distributed. However, for an individual company, the saving rate is just the ratio of the firm's disposable profit over net profit and is primarily affected by the company's propensity to save. In this paper, since we are mainly interested in an individual firm's desire to save, we confine our examination to an analysis of individual companies' saving rates. 3.2. Factors affecting corporate savings Enterprise funds come from both internal and external financing. External financing can be either direct or indirect and involves obtaining funds from the capital market. Internal financing refers to funds that come from firms' retained earnings and depreciation, among other means. According to the Chinese NBS, by the end of 2012, 67.8% of Chinese enterprises' investment funds in fixed assets came from internal financing, far more than that in the early 1990s, when the proportion was only 50%. The fact that Chinese enterprises are increasingly relying on internal financing actually means that firms are increasingly reliant on their savings (Yang et al., 2011). This gives an indication of what the growth of China's national corporate savings is based on. From this we can see that the analysis of the factors affecting corporate savings is in fact equivalent to the analysis of factors influencing corporate financing methods. 3.2.1. Firm specific financial indicators A firm's total assets, sales, current ratio, debt to asset ratio and other financial indicators all have a strong impact on a firm's access to corporate credit, which in turn determine a firm's financing constraints through several channels. There are a number of ways in which firm specific financial indicators can affect a firm's financing constraints, when the financial indicators of firms are regarded as good indicators of the operation performance of firms. First, financial indicators affect a firm's direct financing capability. Firm size and profitability impact investors' confidence in the firm, thus affecting a firm's direct financing capability in the stock market. Second, financial indicators also affect a firm's indirect financing capability. In order to mitigate the default risk of frims and unpredictable market risk, banks are likely to allocate loans based on these indicators, i.e., enterprises with good financial indicators are more likely to receive a loan. Thus, financial indicators also have a real impact on the firm's indirect financing capacity. Third, financial indicators influence a firm's dividend policy. Larger enterprises with strong profitability may have a higher dividend payout ratio, while smaller firms with strong future growth prospects generally tend to expand firm size and reinvest in the market than paying high dividends. They may also be in need of capital and are thus more likely to have higher savings and lower dividends. Finally, potential future investment opportunities will also influence corporate savings via the amount of dividends paid out. In sum, it is clear that financial indicators have a large impact on firms' direct and indirect financing channels. Moreover, a firm's dividend policy is also likely to be influenced by financial indicators to some extent. Thus, we can infer that financial indicators affect corporate savings. 3.2.2. Ownership type and monopoly status Corporate savings are also potentially related to a firms' ownership type and monopoly status. State-owned enterprises (SOEs) usually have greater access to external capital than private enterprises for two reasons. First, state-owned enterprises are subject to tacit policy support from the government, which gives them certain advantages in terms of access to resources and lower external financing costs. Second, China's four major state-owned commercial banks favor SOEs over small and medium enterprises in terms of loan allocation, mainly due to strong political links with SOEs, more symmetric information, and the desire to control risk. However, the low dividends paid out by SOEs have long been criticized. Although the State Council issued “Opinions of the State Council on the Pilot Implementation of the State Capital Operating Budget” in 2007, which stipulated that SOEs should pay dividends to majority shareholders, the actual effectiveness of this on SOEs' dividend policies is uncertain. Dividend payouts still vary among regions and have remained rather low. Given the opposite effects of external financing advantages and low dividend pay-out ratio on the saving rate, it is still unclear what the overall effect will be on SOEs' saving rates compared to that of private enterprises. 28 S. Xie, T. Mo / China Economic Review 33 (2015) 25–34 In addition, whether firms have a monopoly status or not should have an impact on corporate savings. Theoretically, monopolists in a particular industry are able to earn high monopoly profits, i.e., through resource rents. Besides, as monopolies usually occur in strategic industries, which are often of great importance to the national economy, they share a number of similarities with SOEs, one being that they also seldom pay high dividends. Therefore, the facts that the monopolies earn higher profits and that they pay lower dividends both lead to higher saving rates. The above analysis shows that the type of ownership of a firm and whether a firm has a monopoly status should affect firms' financing channels and dividend policies, thus affecting corporate savings. Therefore, we can infer that enterprises of different monopoly statuses and ownership types should have different saving rates. 3.3. Financial development Gurley and Shaw (1955, 1956) define financial development as an increase in the number of financial assets and, particularly, financial institutions. They argue that the higher the degree of economic development, the stronger the impact finance has on the economy. This paper argues that financial development has the following three impacts on corporate savings. First, financial development can improve access to funds for enterprises, relax corporate financing constraints, and therefore reduce corporate savings. Demirguc-Kunt and Maksimovic (2002) contend that a high level of financial development gives investors better access to more relevant and accurate information on firms and thus improves their incentives to invest in the firms. As a result, the supply of external financing for enterprises is increased. Second, financial development is likely to affect the saving behavior of firms of different ownership types in different ways. As explained above, due to the government's implicit guarantee, SOEs are more likely to have direct government subsidies and/ or other financial supports, and also tend to obtain credit at a lower cost than private enterprises from commercial banks. Thus, their financing constraints are much lower. However, financial development can reduce the gap between SOEs and private enterprises by reducing information asymmetry and increasing corporate financing channels for private enterprises. Third, financial development can have an impact on the significance of some financial indicators for corporate saving rates, which further changes corporate saving incentives. For example, financial development can increase market efficiency and deepen market segmentation, allowing investors to be more selective when choosing firms in which they would like to invest. Moreover, when there is a higher degree of financial development, information disclosure is more complete. This will allow investors to judge firm specific risk and profitability level more easily; therefore, smaller enterprises with potential for future growth are more likely to be able to obtain funding, thereby reducing their corporate savings. 4. Empirical methods and data 4.1. Empirical methods Currently there are no common methods for calculating the explanatory variable Saving Rate. For example, Bayoumi et al. (2010) define the corporate saving rate as (net income − dividends) / total assets. This definition is closer to the definition of the net asset profit margin when dividend payouts are low. Conversely, Huang (2011) defines the saving rate as (cash + short-term securities assets) / total assets. In this paper, we define the corporate saving rate as (surplus reserves of the year + retained earnings) / net profit. The reason for using this definition is that among all the components that make up total net profit, surplus reserves and retained earnings are generally freely available for the company's use out of net profits. Thus, they can best reflect the firms' propensity to save. To test the inferences in our theoretical analysis, we set up the following model, Eq. (1), to analyze the impact of financial indicators, ownership type and monopoly status on corporate savings. SavingRatei;t ¼ α 0 þ 6 X α j X i; j;t þ α 7 Stateownedi þ α 8 Monopolyi þ α 9 Yeart þ εi;t ð1Þ j¼1 where Xi,j,t represents a list of six individual financial indicators (j = 1,…,6) of firm i in year t, including the size of the firm (measured by the log of total assets, LnTotalAsset), short-term solvency (measured by the current ratio, CurrentRatio), profitability (measured by return on equity, ROE), long-term solvency (measured by the debt to asset ratio, Debt/Asset), growth (measured by revenue growth, Growth), and investment opportunities (measured by Tobin's Q, Q). Stateownedi is a dummy for state-owned enterprises (Stateownedi = 1 if SOE). This paper defines SOEs as the enterprises whose ultimate controllers are state-owned holding companies according to the CCER (Xenophon Database) database. All others are defined as private enterprises. Monopolyi is a dummy for monopolist (Monopolyi = 1 if monopolist). In this paper, we classify firms as monopolies in accordance with the industry classification standards of the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC). Specifically, we define companies in 24 three-digit sectors, such as coal mining, petroleum, and natural gas extraction, as monopolies. To control for industry fixed effects in the regressions, we also use the industry classification provided by the CSRC. Yeart is a vector of time dummy variables, which accounts for macroeconomic factors, such as interest rates and economic growth. S. Xie, T. Mo / China Economic Review 33 (2015) 25–34 29 We use the next model, Eq. (2), to determine the impact of financial development on the corporate saving rate. SavingRatei;t ¼ α 0 þ X α j X i; j;t þ β1 FDi;t þ β2 FDi;t X i; j;t þ εi;t : ð2Þ j In Eq. (2), Xi,j,t represents the financial indicators, ownership type, monopoly status and year dummy variable. FDi,t represents the degree of regional financial development of the province where the company is registered. The coefficients of interests are β1 and the interaction term coefficient β2, which directly measures how the degree of financial development affects the corporate saving rate and how changes in financial development impact on the other factors listed above, respectively. Goldsmith (1969) was the first to introduce a measure for gauging the extent of a country's financial development. The so-called Financial Interrelations Ratio (FIR) measures the ratio of the market value of the flow of financial assets to total national wealth. However, in China there are huge disparities between regions in terms of financial development; therefore, instead of using the national financial development level, in this paper we define FD as the regional financial development level and calculate the level of financial development in 32 separate provinces or municipalities across mainland China. Due to the difficulty involved in obtaining data on certain province's total financial assets, we refer to the approach adopted by Shen, Kou, and Zhang (2010) and use the ratio of the annual total of a province's financial institutions' loans to annual regional GDP to represent the provincial financial development level. Zhao (2007) also analyzes the level of financial development in various provinces across China by using the FD indicator; however, he defines the financial development of a province as the ratio of the sum of the province's financial institutions' deposits and loans to the province's annual GDP, which is slightly different from ours. This paper will use Zhao's indicator to test the robustness of our model. It should be noted that instead of borrowing from the bank which is mostly affected by the local financial development, there may be other channels for the listed companies to raise funds, such as issuing corporate bonds and additional common shares. The provincial financial development perhaps hardly affects the financial constraints of the companies and their saving rates as well. However, the follow-on offering is not frequent for listed companies in China due to its high costs and bond issuing is also limited as a result of the underdeveloped bond market. Therefore, given the particular situation in China, provincial financial development can act as a good proxy for the financing constraint of the listed companies in our empirical model. 4.2. Data Our data is compiled from RESSET (RESSET Database) and CCER (Xenophon Database), as well as the Almanac of China's Finance and Banking. Our data comprises information on all non-financial companies listed on the Shanghai and Shenzhen Stock Exchanges from 2003 to 2012. To be more specific, the data on financial indicators, namely firms' financial data, is compiled from RESSET, while data on ownership type and monopoly status, such as data on ultimate controlling structures and industry classification, is compiled from CCER. Finally, we gather the necessary data needed to measure provincial financial development in China from the Almanac of China's Finance and Banking. Our final dataset is formed as follows: (1) in line with the method to calculate the corporate saving rate outlined above, we exclude all saving rates that are negative or larger than one; (2) we exclude any data from Special Treatment enterprises in the sample period; (3) we select all enterprises that appear more than once during the sample period to avoid potentially misleading corporate accounting indicators from companies that only appear once; and (4) we remove any enterprises with missing data. After sample selection, we have a total of 8771 data sample observations. 85 Saving Rate (%) 80 75 70 65 60 55 50 2003 2004 2005 2006 Eastern China Central China 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 Western China The Whole Sample Fig. 1. Corporate saving rates in different regions. Notes: Eastern China includes Beijing, Tianjing, Shenzhen, Hebei, Liaoning, Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Fujiang, Shandong, Guangdong, Guangxi, and Hainan. Central China includes Shanxi, Inner Mongolia, Jilin, Heilongjiang, Anhui, Jiangxi, Henan, Hubei, and Hunan. Western China includes Chongqing, Sichuan, Guizhou, Yunnan, Tibet, Shaanxi, Gansu, Qinghai, Ningxia, and Xinjiang. The whole sample includes all the 32 provinces and municipalities. Data source: RESSET Database. 30 S. Xie, T. Mo / China Economic Review 33 (2015) 25–34 To show the differences in corporate saving rates across the different provinces, Fig. 1 shows the trends in corporate saving rates in eastern, central and western provinces of China from 2003 to 2012. A longitudinal comparison shows that the overall saving rate increased after 2006 in all provinces. However, other studies have slightly different results, for example, Kuijs (2005) argues that China's corporate savings increased massively after 2002, and Huang (2011) shows that the corporate saving rate in China began to rise in 1998 and exceeded the household saving rate in 2000. Nevertheless, these studies concur with our general conclusion that the corporate saving rate has been steadily growing for a significant period of time. Besides, an evident decrease in the saving rate occurred in 2012, which mainly due to the mandatory dividend policy stressed by the China Securities Regulatory Commission and a relevant draft policy enacted by the Shanghai Securities Exchanges, which requires the listed companies with a dividend ratio less than 30% to disclose the reason. Although this disclosure requirement is not eventually imposed, the dividends of the listed companies in 2012 might be affected by the opinions of the regulatory administrations. A horizontal comparison of the trends shows that corporate saving rates in the central provinces of China are generally higher than those of the western provinces, while the eastern provinces have the lowest saving rates. According to our calculations, the average FD value for the central provinces is the lowest of the three regions, followed by the average of the western provinces, while the average FD value for the eastern provinces is the highest. Since the eastern provinces are the most developed and the financial institutions in these provinces are extremely intensive, it is no surprise that they have the highest level of financial development; however, the reasons behind lower values in the central provinces compared to the western provinces are not so clear. We mainly attribute this to the extra credit support given to many of the western provinces since the year 2000 as part of the government strategy to develop the west of China. Considering these preliminary results, we deduce that financial development does have a significant impact on corporate saving rates in China. Table 2 reports the descriptive statistics for each variable. In order to avoid any influence of outliers on our statistics, we winsorize all the continuous variables, except for the FD value, at the 1% level. In addition, all the financial indicators here and in the following regressions are multiplied by 100, except LnTotalAsset and Q. 5. Results 5.1. The impact of firm specific financial indicators, ownership type and monopoly status on corporate saving rates Table 3 reports the regression results of Eq. (1). To control for the influence of macroeconomic factors, we include time fixed effects in each regression. In the first column of Table 3, we only control for financial indicators, while in Column 2, both financial indicators and industry fixed effects are included. The regression results show that: (1) the larger the enterprise, the lower the saving rate; (2) a firm's short-term solvency does not significantly affect its saving rate, but its long-term solvency does have a significant influence; and (3) a firm's growth, profitability, and investment opportunities do not have significant impact on its saving rate. Obviously, it seems that only part of the six indicators work in determining the corporate saving rates. Columns 3 to 6 of Table 3 show the regression results for ownership type and monopoly status. The results in Column 3 indicate that SOEs have lower saving rates than private companies, which is however insignificant. When industry fixed effects are controlled for, the difference remains insignificant. Actually, Bayoumi et al. (2010) also find that the differences in saving rates between SOEs and private enterprises are not evident when controlling for the type of industry. These results hence suggest that the difference in saving rates between SOEs and private enterprises is indistinguishable. As our previous analysis predicts, this insignificance is highly attributable to the mixed features of low external financial constraints and low dividend payout ratios of the SOEs. Since controlling for industry fixed effects might be too restrictive, Column 5 shows our regression results when we only control for monopoly status. These results show that firms that have monopoly power in an industry have significantly higher saving rates, confirming our inference in the theoretical analysis. Besides, when ownership type is added in Column 6, the results remain significant. Therefore, though we cannot find a significant difference in the saving rates of private enterprises and SOEs, the disparity in the saving rates of non-monopolies and monopolies is indeed evident. Table 2 Descriptive statistics of independent variables.Data source: The data on financial indicators is from RESSET Database; the data on ownership type and monopoly status is from Xenophon Database; the data on provincial financial development is from the Almanac of China's Finance and Banking, 2004–2013. Variable Sample Mean Std Min Max LnTotalAsset CurrentRatio ROE Debt/Asset Growth Q Stateowned Monopoly FD 8771 8771 8771 8771 8771 8771 8771 8771 8771 21.77 1.97 10.73 46.07 21.52 1.83 0.61 0.31 1.26 1.17 2.04 8.47 18.70 31.38 1.05 0.49 0.46 0.53 19.60 0.28 −16.13 5.77 −43.70 0.87 0.00 0.00 0.40 25.35 13.51 39.16 82.67 164.04 6.63 1.00 1.00 3.29 Notes: LnTotalAsset is the natural logarithm of total assets. CurrentRatio is the current ratio. ROE is the return on equity. Debt/Asset is the debt to asset ratio. Growth is the revenue growth. Q is the Tobin's Q. All the financial indicators except LnTotalAsset and Q are multiplied by 100. Stateowned and Monopoly are dummies. FD is the financial development. S. Xie, T. Mo / China Economic Review 33 (2015) 25–34 31 Table 3 Determinants of saving rate—financial indicators.Data source: The data on financial indicators is from RESSET Database; the data on ownership type and monopoly status is from Xenophon Database; the data on provincial financial development is from the Almanac of China's Finance and Banking, 2004–2013. Variables (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) LnTotalAsset −2.924⁎⁎⁎ (0.448) −0.218 (0.259) 0.019 (0.058) 0.142⁎⁎⁎ (0.032) 0.017 (0.011) −0.231 (0.438) −3.211⁎⁎⁎ (0.550) −0.268 (0.209) 0.026 (0.060) 0.133⁎⁎⁎ (0.033) 0.015 (0.010) 0.077 (0.357) −2.888⁎⁎⁎ (0.465) −0.224 (0.263) 0.017 (0.058) 0.142⁎⁎⁎ (0.032) 0.017 (0.011) −0.226 (0.444) −0.248 (1.010) −3.230⁎⁎⁎ (0.558) −0.265 (0.214) 0.027 (0.061) 0.133⁎⁎⁎ (0.033) 0.015 (0.011) 0.073 (0.367) 0.177 (1.082) −3.215⁎⁎⁎ (0.463) −0.264 (0.256) 0.016 (0.059) 0.140⁎⁎⁎ (0.033) 0.016 (0.011) −0.190 (0.433) YES NO 8771 0.069 YES YES 8771 0.101 −3.151⁎⁎⁎ (0.479) −0.276 (0.260) 0.013 (0.060) 0.139⁎⁎⁎ (0.033) 0.015 (0.011) −0.180 (0.440) −0.489 (1.006) 2.745⁎⁎⁎ (0.795) YES NO 8771 0.071 CurrentRatio ROE Debt/Asset Growth Q Stateowned Monopoly Year FEs Industry FEs Observations R2 YES NO 8771 0.069 YES YES 8771 0.101 2.701⁎⁎⁎ (0.797) YES NO 8771 0.071 Notes: (1) LnTotalAsset is the natural logarithm of total assets. CurrentRatio is the current ratio. ROE is the return on equity. Debt/Asset is the debt to asset ratio. Growth is the revenue growth. Q is the Tobin's Q. All the financial indicators except LnTotalAsset and Q are multiplied by 100. Stateowned and Monopoly are dummies. FD is the financial development. (2) The cells show coefficients with robust standard errors in parentheses. Constants are not reported. Year FEs denote year fixed effects and Industry FEs denote industry fixed effects. ⁎ p b 0.1. ⁎⁎ p b 0.05. ⁎⁎⁎ p b 0.01. 5.2. The impact of financial development on corporate saving rates Table 4 reports the impact of financial development on corporate saving rates. Column 1 reports the regression results for all enterprises, controlling for year and industry fixed effects. From the regression results, we can see that the coefficient on FD is negative Table 4 Determinants of saving rate-financial development.Data source: The data on financial indicators is from RESSET Database; the data on ownership type and monopoly status is from Xenophon Database; the data on provincial financial development is from the Almanac of China's Finance and Banking, 2004–2013. Variables All companies Private Stateowned Non-monopoly Monopoly LnTotalAsset −2.984⁎⁎⁎ (0.521) −0.245 (0.211) 0.025 (0.060) 0.123⁎⁎⁎ (0.032) 0.014 (0.010) 0.074 (0.359) −3.005⁎⁎⁎ (0.945) YES YES 8771 0.104 −4.297⁎⁎⁎ (0.909) −0.426 (0.296) 0.106 (0.103) 0.175⁎⁎⁎ (0.042) 0.026⁎ −2.143⁎⁎⁎ (0.564) 0.222 (0.391) −0.051 (0.051) 0.090⁎⁎ (0.041) 0.010 (0.013) 0.619 (0.411) −3.065⁎⁎⁎ (0.843) YES YES 5367 0.127 −3.832⁎⁎⁎ (0.820) −0.371 (0.250) 0.001 (0.077) 0.164⁎⁎⁎ (0.034) 0.025⁎ −1.747⁎⁎ (0.701) 0.251 (0.469) 0.115 (0.084) 0.049 (0.068) −0.000 (0.013) −0.596 (0.606) −3.622⁎⁎ (1.335) YES YES 2712 0.121 CurrentRatio ROE Debt/Asset Growth Q FD Year FEs Industry FEs Observations R2 (0.015) −0.370 (0.655) −3.500⁎ (1.946) YES YES 3404 0.123 (0.014) 0.242 (0.432) −2.601⁎⁎ (1.231) YES YES 6059 0.103 Notes: (1) LnTotalAsset is the natural logarithm of total assets. CurrentRatio is the current ratio. ROE is the return on equity. Debt/Asset is the debt to asset ratio. Growth is the revenue growth. Q is the Tobin's Q. All the financial indicators except LnTotalAsset and Q are multiplied by 100. Stateowned and Monopoly are dummies. FD is the financial development. (2) The cells show coefficients with robust standard errors in parentheses. Constants are not reported. Year FEs denote year fixed effects and Industry FEs denote industry fixed effects. ⁎ p b 0.1. ⁎⁎ p b 0.05. ⁎⁎⁎ p b 0.01. 32 S. Xie, T. Mo / China Economic Review 33 (2015) 25–34 and significant, indicating that financial development can significantly reduce the saving rates of all firms by 3% overall. Since the significance of the financial indicators does not change after including the financial development variable, this indicates that our previous regression results are robust. Our previous analysis indicates that different levels of monopoly power have significantly different impacts on firms' savings structures. However, other control variables may also have different levels of influence on corporate saving. Therefore, it may be unreasonable to pool all enterprises together in our regressions when investigating the impact of financial development on corporate saving rates. With this in mind, we begin by not using an interaction term for the dummy variables and financial development variable, but instead divide our data by enterprise type, as in the previous section, and conduct separate regressions for each type. The regression results are shown in Columns 2 to 5 in Table 4. The results show that financial development has significantly different impacts on the saving rates of different types of enterprises. One more unit of financial development can reduce the saving rates of state-owned monopolies, private enterprises, non-monopolies, and monopolies by 3.500%, 3.065%, 2.601%, and 3.622% respectively. The estimates are significant for all categories of companies at 1% level. The results strongly convince us that financial development can relieve the financing constraint faced by firms and thus reduce their propensity to save their earnings. This also explains why the firms in eastern China where the level of financial development is higher have much lower saving rates than firms in other regions. With regard to the significance of the financial indicators, we find that only the debt to asset ratio for monopolies is different from the whole sample and others do not change much. This suggests that the factors affecting corporate saving rates vary little for different types of enterprise. Since it is widely used to include an interaction term of financial indicator with financial development in the study of financial development and financing constraints, we also use this method and Table 5 reports the regression results. The interaction terms are only significant in Columns 2 and 3. In other columns, the interaction terms are not significant, which suggests that changes in the level of financial development do not significantly change the impact of these financial indicators on saving rates. However, column 2 shows that after including the interaction term for the level of financial development and the current ratio, the current ratio is negative and significant at the 1% level and the coefficient on the interaction term is positive and significant at the 1% Table 5 Interactions between financial development and financial indicators.Data source: The data on financial indicators is from RESSET Database; the data on ownership type and monopoly status is from Xenophon Database; the data on provincial financial development is from the Almanac of China's Finance and Banking, 2004–2013. Variables (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) LnTotalAsset −3.242⁎⁎⁎ (0.781) −0.240 (0.212) 0.026 (0.060) 0.124⁎⁎⁎ −2.962⁎⁎⁎ (0.519) −1.092⁎⁎⁎ (0.384) 0.026 (0.060) 0.117⁎⁎⁎ −2.984⁎⁎⁎ (0.517) −0.246 (0.208) −0.293⁎⁎ (0.128) 0.122⁎⁎⁎ −2.980⁎⁎⁎ (0.522) −0.257 (0.203) 0.025 (0.060) 0.140⁎⁎ −2.991⁎⁎⁎ (0.519) −0.242 (0.211) 0.028 (0.060) 0.124⁎⁎⁎ −2.979⁎⁎⁎ (0.521) −0.248 (0.208) 0.025 (0.060) 0.123⁎⁎⁎ (0.032) 0.014 (0.010) 0.078 (0.357) −7.131 (8.095) 0.189 (0.352) (0.032) 0.013 (0.010) 0.067 (0.352) −4.312⁎⁎⁎ (0.032) 0.013 (0.010) 0.052 (0.344) −5.846⁎⁎⁎ (0.989) (1.554) (0.067) 0.014 (0.010) 0.073 (0.359) −2.381 (2.327) (0.032) −0.018 (0.023) 0.071 (0.360) −3.545⁎⁎⁎ (1.177) (0.032) 0.014 (0.010) −0.166 (0.958) −3.353⁎⁎ (1.431) −2.910⁎⁎⁎ (0.997) −1.417⁎⁎⁎ (0.477) −0.288⁎⁎ (0.122) 0.059 (0.087) 0.004 (0.019) 0.634 (0.904) −7.899 (10.212) −0.052 (0.525) 0.826⁎⁎ (0.325) 0.264⁎⁎⁎ (0.086) 0.046 (0.065) 0.007 (0.015) −0.468 (0.630) YES YES 8771 0.107 CurrentRatio ROE Debt/Asset Growth Q FD FD ∗ LnTotalAsset FD ∗ CurrentRatio 0.575⁎⁎⁎ (0.190) FD ∗ ROE 0.266⁎⁎⁎ (0.091) FD ∗ Debt/Asset −0.014 (0.043) FD ∗ Growth 0.024 (0.020) FD ∗ Q Year FEs Industry FEs Observations R2 YES YES 8771 0.104 YES YES 8771 0.105 YES YES 8771 0.106 YES YES 8771 0.104 YES YES 8771 0.104 0.190 (0.677) YES YES 8771 0.104 Notes: (1) LnTotalAsset is the natural logarithm of total assets. CurrentRatio is the current ratio. ROE is the return on equity. Debt/Asset is the debt to asset ratio. Growth is the revenue growth. Q is the Tobin's Q. All the financial indicators except LnTotalAsset and Q are multiplied by 100. Stateowned and Monopoly are dummies. FD is the financial development. (2) The cells show coefficients with robust standard errors in parentheses. Constants are not reported. Year FEs denote year fixed effects and Industry FEs denote industry fixed effects. ⁎ p b 0.1. ⁎⁎ p b 0.05. ⁎⁎⁎ p b 0.01. S. Xie, T. Mo / China Economic Review 33 (2015) 25–34 33 level as well. However, our previous regression results suggest that corporate short-term solvency does not significantly affect corporate saving rates. This means that when the level of financial development is low, a firm's short-term solvency has a greater impact on its ability to borrow; thus, firms with better short-term solvency are less dependent on internal financing and have lower saving rates. However, with a higher level of financial development, market is more efficient, information asymmetry declines, and investors are able to track firms' debt levels more closely, which allows them to adjust any investment decision rapidly. Therefore, investors may not necessarily avoid investing in enterprises with good long-term prospects but poor short-term solvency. This reduces the financing constraints resulted from a firm's solvency and, thus, the impact of solvency on corporate savings decreases accordingly. The results in Column 3 of Table 5 show that both the coefficients on ROE and FD are significant at the 1% level after adding an interaction term of these two variables, despite the fact that our previous regression results indicate that firm profitability does not significantly affect corporate saving rates. The results indicate that when the level of financial development is low, a firm's saving rate is affected by its profitability. Firms with stronger profitability have better access to loans, resulting in the relatively low saving rates. As the level of financial development increases, the investment objectives of investors in the capital market become increasingly diversified. As pursuing profits becomes the most important one among all objectives, the financing constraints resulted from profitability decrease and thus the impact of profitability on corporate saving rates becomes less significant. In addition to interacting the financial development term with each financial indicator, we also collectively incorporate all of the six interaction terms into the regression together to verify the robustness of the results. The results are shown in Column 7. Evidently, the results are consistent as the interactions between financial development and current ratio and ROE are both positive and significant. The only difference is that the coefficients on debt to asset ratio and financial development are no longer significant in this regression. 5.3. Robustness check In order to further validate the impact of financial development on saving rates, this paper carries out two robustness tests. First, following Zhao (2007), we use the regional financial interrelation ratio, or RFIR, which is the sum of total deposits and loans from financial institutions located in each province divided by that province's GDP, as a proxy for financial development in our regression. The results are reported in Table 6. Apparently, the regression results using the alternative financial development proxy are the same with results found earlier in this paper, suggesting that our results of the impact of financial development on corporate saving rates are robust. Second, to validate our results for the interaction effects between financial development and financial indicators, this paper follows the method of Ozer-Balli and Sørensen (2010). We introduce the square of the main interaction term into the regression model to ascertain that we are not picking up the effect of the square term. We find that the significance of each variable does not change, suggesting that our previous regression results regarding the interaction terms are also robust. For brevity's sake, the results are not reported here but are available from the authors upon request. In sum, it seems that our conclusions of the impact of financial development on saving rates are valid and credible. Table 6 Determinants of saving rate-financial development using RFIR.Data source: The data on financial indicators is from RESSET Database; the data on ownership type and monopoly status is from Xenophon Database; the data on provincial financial development is from the Almanac of China's Finance and Banking, 2004–2013. Variables All companies Private Stateowned Non-monopoly Monopoly LnTotalAsset −2.980⁎⁎⁎ (0.314) −0.232 (0.201) 0.022 (0.037) 0.124⁎⁎⁎ (0.022) 0.014 (0.009) 0.091 (0.322) −0.942⁎⁎⁎ (0.191) YES YES 8771 0.103 −4.283⁎⁎⁎ (0.567) −0.414 (0.277) 0.099⁎ (0.057) 0.176⁎⁎⁎ (0.038) 0.027⁎⁎ −2.111⁎⁎⁎ (0.398) 0.236 (0.309) −0.051 (0.050) 0.089⁎⁎⁎ (0.028) 0.011 (0.013) 0.643 (0.484) −1.103⁎⁎⁎ (0.232) YES YES 5367 0.127 −3.859⁎⁎⁎ (0.422) −0.367 (0.232) −0.002 (0.044) 0.166⁎⁎⁎ (0.028) 0.026⁎⁎ −1.691⁎⁎⁎ (0.464) 0.277 (0.405) 0.115⁎ (0.069) 0.049 (0.038) −0.000 (0.014) −0.566 (0.681) −1.260⁎⁎⁎ (0.308) YES YES 2712 0.122 CurrentRatio ROE Debt/Asset Growth Q FD Year FEs Industry FEs Observations R2 (0.013) −0.350 (0.434) −0.792⁎⁎ (0.355) YES YES 3404 0.120 (0.012) 0.254 (0.366) −0.736⁎⁎⁎ (0.241) YES YES 6059 0.102 Notes: (1) LnTotalAsset is the natural logarithm of total assets. CurrentRatio is the current ratio. ROE is the return on equity. Debt/Asset is the debt to asset ratio. Growth is the revenue growth. Q is the Tobin's Q. All the financial indicators except LnTotalAsset and Q are multiplied by 100. Stateowned and Monopoly are dummies. FD is the financial development. (2) The cells show coefficients with robust standard errors in parentheses. Constants are not reported. Year FEs denote year fixed effects and Industry FEs denote industry fixed effects. ⁎ p b 0.1. ⁎⁎ p b 0.05. ⁎⁎⁎ p b 0.01. 34 S. Xie, T. Mo / China Economic Review 33 (2015) 25–34 6. Conclusion Although China's economy is experiencing rapid growth, it is based on an unbalanced economic structure. In 2012, China's GDP growth rate was 7.7%, which was the first time that its GDP growth rate dropped below 8% since 2000. The problems caused by the current development strategy, i.e., high savings and investment growth, are increasingly prominent. Therefore, solving the problem of high saving rates, especially high corporate saving rates, is of great importance and urgency. Based on an empirical analysis of 8771 companies listed on the Chinese stock markets between 2003 and 2012, this paper examines the determinants of corporate saving rates, especially from the new perspectives of ownership type, monopoly status, and financial development. We come to the following four conclusions. First, firms with smaller size and weaker long-term solvency have higher corporate saving rates. Other corporate financial indicators such as short-term solvency, profitability and investment opportunities do not significantly influence corporate saving rates. Second, the saving rates of different enterprises vary with their monopoly status. Specifically, monopolies have nearly 2.7% higher saving rates than non-monopolies. However, the difference between private enterprises and SOEs is insignificant. As explained in our theoretical analysis, the insignificant disparity between private enterprises and SOEs is resulted from the opposite effects of less financial constraints and lower dividend ratios for SOEs. Third, financial development can significantly reduce corporate saving rates. However, the impacts of financial development on saving rates differ among companies of different monopoly statuses and ownership types. The empirical results suggest that, ceteris paribus, one additional unit of financial development can significantly reduce the saving rates of private and state-owned enterprises by 3.500% and 3.065%, respectively. Financial development can also significantly reduce saving rates of non-monopolies and monopolies by 2.601% and 3.622%, respectively. Fourth, the level of financial development can affect the effects of short-term solvency and profitability on corporate saving rates. When the level of financial development is low, corporate saving rates are influenced by firms' short-term solvency and profitability, i.e., the stronger the profitability and the better the short-term solvency, the lower the corporate saving rate. However, as financial development improves, the impact of the two indicators on corporate financing constraints diminishes. Though limited, the results in our paper are significant to tackle the problem of high corporate saving rates in China. Our analysis indicates that in addition to the financial fundamentals of the enterprises, the monopoly status of an enterprise and the financial development of their registered locations both play important roles in determining their saving rates. Thus, reducing the monopoly power in some industries and promoting financial development may serve as good options for the Chinese government to address the saving puzzle. References Bayoumi, T., Tong, H., & Wei, S.J. (2010). The Chinese corporate savings puzzle: A firm-level cross-country perspective. NBER Working Paper, No.16432. Demirguc-Kunt, A., & Maksimovic, V. (2002). Funding growth in bank-based and market-based financial systems: Evidence from firm-level data. Journal of Financial Economics, 65, 337–363. Goldsmith, R.W. (1969). Financial structure and development. New Haven: Yale University Press. Gurley, J.G., & Shaw, E.S. (1955). Financial aspects of economic development. American Economic Review, 45(4), 515–538. Gurley, J.G., & Shaw, E.S. (1956). Financial intermediaries and the saving–investment process. The Journal of Finance, 11(2), 257–276. He, X., & Cao, Y. (2007). Understanding high saving rate in China. China & World Economy, 15(1), 1–13. Horioka, C.Y., & Wan, J. (2007). The determinants of household saving in China: A dynamic panel analysis of provincial data. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 39(8), 2077–2096. Huang, Y. (2011). Can the precautionary motive explain the Chinese corporate savings puzzle? International Monetary Fund. Working paper. Kraay, A. (2000). Household saving in China. The World Bank Economic Review, 14(3), 545–570. Kuijs, L. (2005). Investment and saving in China. World Bank policy research working paper, no. 3633. Ma, G., & Yi, W. (2010). China's high saving rate: Myth and reality. International Economics, 122, 5–39. Ozer-Balli, H., & Sørensen, B.E. (2010). Interaction effects in econometrics. CEPR papers, no 7929. Shen, Hongbo, Kou, Hong, & Zhang, Chuan (2010). An empirical study of financial development, financing constraints and corporate investment. China Industrial Economics, 6 (In Chinese). Wei, S.J., & Zhang, X. (2009). The competitive saving motive: Evidence from rising sex ratios and saving rates in China. NBER working paper no. 15093. Xu, Shengyan, Zhou, Mi, & Zhao, Gang (2011). Reasons for Chinese high corporate saving rate. Modern Management Science, 1 (In Chinese). Yang, D.T., Zhang, J.S., & Zhou, S.J. (2011). Why are saving rates so high in China? IZA discussion paper no. 5465. Zhao, Nan (2007). The statistical descriptive on regional financial development in China. Statistical Research, 6.

© Copyright 2026