!"#$%&'(%)*%+,--,./%01%2-$3(',3,(1!4%"#$%560-,7$%8.9%(#$%2-$3(',3%:#8,' &6(#)';<=4%>?'/$.%@8'(<3#6A8(

!"#$%&'(%)*%+,--,./%01%2-$3(',3,(1!4%"#$%560-,7$%8.9%(#$%2-$3(',3%:#8,'

&6(#)';<=4%>?'/$.%@8'(<3#6A8(

5)6'3$4%"#$%>)6'.8-%)*%&7$',38.%B,<()'1C%D)-E%FGC%H)E%I%;J$3EC%KLLK=C%MME%GLLNGKO

P60-,<#$9%014%Q'/8.,R8(,).%)*%&7$',38.%B,<()',8.<

5(80-$%STU4%http://www.jstor.org/stable/3092345

&33$<<$94%KVWLFWKLLF%LG4XI

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless

you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you

may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use.

Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at

http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=oah.

Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed

page of such transmission.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the

scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that

promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

http://www.jstor.org

"The

The

Art

of

Sublime

Killing

by Electricity":

and

the

Electric

Chair

Jiirgen Martschukat

In July 1896, an articlein the ScientificAmericanpraised"The Progressof Invention

during the Past Fifty Years."The author, EdwardW. Byrn, celebrated"a splendid,

brilliantcampaignof brainsand energy,rising to the highest achievementamid the

most fertileresources."New technologicaldevicesof incrediblerichnessand diversity

had been invented, immense progressand marvelousgrowth had been achieved,and

people felt overwhelmedby a "gigantictidal wave"or "flashingmeteors that burst

upon our vision."Accordingto Byrn, the Westernworld had been createdanew by

the modern, especiallythe American,man who had touched matter "withthe divine

breathof thought"and had thus acquiredalmost supernaturalqualities.This technological enlightenmentinspired"emotionsof wonder and admirationat the resourceful and dominant spirit of man." Thus, according to Byrn, the man-made but

neverthelesshardlycomprehensibleworld of technologicalwonder caused a sublime

experienceamong late-nineteenth-centuryAmericans.'

In the middle of this world of technologicalwonder stood the electricchair,which

was developed for the execution of the death penalty in New YorkState during the

1880s. When electricity and capital punishment merged in the "deadlydynamo,"

death by electrocutionwas widely perceivedas an advanceof civilization.It was part

of the remodeled, modern world describedin the ScientificAmericanand in many

more magazinesand writings, and, as such, it was understoodto give society a sense

of elevation. Though the electric chair was an incorporationof a still-mysterious

power, it seemed to signify the human ability-or at least that of white educated

males-to understandapparentlysupernaturalforces, to conquer them, and to use

them for positive, culturallybeneficialeffects. Looking at the history of the electric

chair through the lens of the sublime helps explain how the electrocution of four

death row inmates on July 7, 1891, in Sing Sing state prison could have been celeThisessayreceivedthe David

is professorof historyat the Universityof Hamburg,Germany.

JiirgenMartschukat

Das Erhabeneund der

ThelenPrizefor2002. It firstappearedin Germanas "'TheArtof Killingby Electricity':

ElektrischeStuhl"in Amerikastudien/American

Studies,45 (Fall 2000).

I wouldlike to thankNorbertFinzsch,AlfredHornung,JensJager,MichelleMart,AlexanderRichter,Olaf

Stieglitz,DavidWalker,andthe membersof the ThelenPrizeCommitteefortheircommentson earlierdraftsof

thisarticle.

at <[email protected]>.

ReadersmaycontactMartschukat

1EdwardW. Byrn,"TheProgress

of Inventionduringthe PastFiftyYears,"

American,

July25, 1896,

Scientific

pp. 82-83.

900

The Journalof AmericanHistory

December 2002

The Sublimeandthe ElectricChair

901

and as furtheradvancementin "theart of

bratedas a "greatscientificexperiment"

killingby electricity."2

of technology,conceptsof

The followingarticleinvestigatesthe interrelationship

progress,the sense of the sublime,and the death penaltyin nineteenth-century

the sublimenot as confined

America.I will tryto accomplishthisby conceptualizing

to an aesthetictheory,but ratheras a well-established

patternof discourseshaping

mode of perception,thought,and action.I will then narrowthe

the contemporary

field to the perceptionof electricityand finallyto that of the electricchairand the

firstelectricexecutionsin the early1890s.

The Sublime

With the Enlightenment,the humanabilityto subdueand controlnaturalpowers

becamea crucialelementin the conceptof civilization.To the enlightenedcontemporariesof the eighteenthcentury,mankindwas continuallyimprovingits comprehensionandcontrolof naturalforcesby systematizing

themandestablishing

the laws

of theiroperation.The systematicnatureof the world,not the incomprehensibility

of manyof its phenomena,gavereasonto exaltthe Creator.The God-givenhuman

werethefounabilityto reasonandthe corresponding

potentialforself-development

dationuponwhicha new culturalorderwouldbe created.Evenin the Age of Reason, however,therewas a widespreaddesireto confrontimpenetrable,

mysterious

a desireintenselydisphenomenaandto experiencefear,wonder,andbewilderment,

cussedby numerouswriters.Manypeoplesoughtproximityto tragedy,horrifying

naturalforcessuchas lightningandthunder.Encounters

spectacles,andthreatening

withdeathwereconsideredparticularly

becausedeath

experiences

alluringborderline

wasinevitableandunimaginable

at the sametime,as ImmanuelKantmaintainedin

an essayabout"theend of all existence."Confrontations

with such overwhelming

had

to

be

indirect.

The

confrontation

had to cause

however,

phenomena,

generally

realhorrorfor at leasta fractionof a second,but the observerhad to perceivethe

incidentfroma positionof safetythatguaranteed

his survival.Underthesecircumstances,a horrifyingconfrontationled to an extremelyintenseexistentialawareness

2

The phrase "theart of killing by electricity"comes from Alfred Southwick, quoted in New YorkTimes,July 8,

1891, p. 2. "Deadly dynamo" was a common synonym for the electric chair; see, for instance, New YorkTimes,

April 30, 1890, p. 1. On the history of the electric chair with a focus on technological advancement, see Roger

Neustadter, "The 'Deadly Current':The Death Penalty in the IndustrialAge,"Journal of American Culture, 12

9 (Spring

(Fall 1989), 79-87; and James Penrose, "InventingElectrocution,"Heritageof Invention & Technology,

1994), 34-45. For questions of constitutionality, see Deborah W. Denno, "Is Electrocution an Unconstitutional

Method of Execution?The Engineering of Death over the Century," William and Mary Law Review,35 (Spring

1994), 551-692. On the public, see Michael Madow, "ForbiddenSpectacle:Executions, the Public, and the Press

in Nineteenth-Century New York,"BuffaloLaw Review,43 (Fall 1995), 461-562. On the meaning of pain and

the medical discourse,see JiirgenMartschukat,"'The Death of Pain':Erorterungenzur Verflechtungvon Medizin

und Strafrechtin den USAin der zweiten Hailftedes 19. Jahrhunderts"("The death of pain":On the interdependence of medicine and criminal law in nineteenth-centuryAmerica), in Geschichteschreibenmit Foucault(Writing

history with Foucault), ed. JiirgenMartschukat(New York,2002), 126-48; Craig Brandon, TheElectricChair:An

UnnaturalAmericanHistory(Jefferson,1999); Jiirgen Martschukat,Die Geschichteder Todesstrafe

in Nordamerika

(The history of capital punishment in North America) (Munich, 2002), 81-93; and Stuart Banner, The Death

Penalty:An AmericanHistory(Cambridge, Mass., 2002), 169-96. I have translatedinto English quotations from

and titles of German sources.

902

The Journalof AmericanHistory

December2002

for the observer,and as such the frighteningexperiencewas at the same time joyful,

pleasant,and desirable.3

The quest for "delightfulhorror"was based on pure sensualdesire,but those who

were able intellectuallyto penetratetheir desireand who becameawareof their emotion and attraction elevated themselves to a higher intellectual and cultural level.

They conquerednot only frighteningnaturalphenomena but also their own fear by

means of a strong mind, education, and willpower.They transformednature into

culture, elevated themselves above the outside world, enhanced the perfection of

their individualas well as their collectiveself-controland intellect, and advancedcivilization as a result. In earliertimes, by contrast, confrontationwith expressionsof

naturaland divine powershad causedamazement,horror,and fear,but within a civilized mind it createdan enhancing,sublime feeling. Thus, a supposedlysupernatural

experiencewas transformedinto a sourceof individualand collectiveinspirationand

development.4

A position of safety guaranteeingthe survivalof the observercould be createdby

various means. Being under a shelter during a storm could make a sublime experience possible. The lightning rod, a technologicaldevelopment, functioned as a virtual shelter.It not only enabledpeople to observethunderstormsin closer proximity

and thus more intensively,but it also made the observersfeel a superiorityover the

initial incomprehensibilityand menace of the storm. The naturalspectaclestill had

the abilityto causehorrorand fear,but they could be conqueredby means of human

inventivenessand transformedinto a sublime sensationwithin the observers.5

3 Immanuel Kant, "Das Ende aller Dinge" (The end of all existence), in KantsgesammelteSchriften,1. Abt.:

Werke,vol. 8: Abhandlungennach 1781 (Kant'scollected writings, part 1: Works, vol. 8: Elaborationsafter 1781),

ed. K6nigl. Preug. Akad. der Wissenschaften (Berlin, 1912), 325-39. For a comment on Kant'sessay,see Florian

R6tzer,"Zur Genese des Erhabenen"(On the genesis of the sublime), in Der Scheindes Schinen (On beauty), ed.

Dietmar Kamper and Christoph Wulf (G6ttingen, 1989), 71-99. Another crucial text that before the Civil War

went through at least ten editions in the United Statesis Edmund Burke,A PhilosophicalEnquiryInto the Originof

Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful (1757; London, 1767). David E. Nye, American TechnologicalSublime

(Cambridge,Mass., 1994), 4. On the delightful horror,see Andrew Ashfield and Peter de Bolla, "Introduction,"

AestheticTheory,ed. Andrew Ashfield and Peter de Bolla

in The Sublime:A Readerin BritishEighteenth-Century

Grauen"'Literaturhistorische

(New York, 1996), 1-16; CarstenZelle, 'Angenehmes

BeitrdgezurAsthetikdes Schrecklichen im achtzehntenJahrhundert("Adelightful horror":A literaryhistory of the aesthetic of horror in the eighteenth century) (Hamburg, 1987); Winfried Wehle, "Das Erhabene:Aufkldrungdurch Aufregung"(The sublime:

Enlightenment through excitement), in Das 18. Jahrhundert:Aufklirung (The 18th century: Enlightenment), ed.

Paul Geyer (Regensburg,1995), 9-22.

4 See, from the large body of literatureon the "sublime,"Christine Pries,ed., Das Erhabene:ZwischenGrenzerfahrung und GrofJenwahn(The sublime: Between borderline experience and delusion of grandeur) (Weinheim,

1989); and Rob Wilson, AmericanSublime: The Genealogyof a Poetic Genre(Madison, 1991). Besides Burke's

PhilosophicalInquiry Into .. . the Sublime and Beautiful and the writings compiled by Ashfield and de Bolla,

another outstanding eighteenth-centurytext is Immanuel Kant, "Kritikder Urteilskraft"(Critique of judgment)

(1790), in Kant'sgesammelteSchriften,1. Abt.: Werke,vol. 5 (Kant'scollected writings, part 1: Works, vol. 5) (Berlin, 1913), 165-485, esp. the chaptersfollowing p. 260.

5 Christine Pries, Ubergdngeohne Bricken: KantsErhabeneszwischenKritik und Metaphysik(Transferswithout

bridges: Kant'ssublime between critique and metaphysics) (Berlin, 1995), 38-75. On the lightning rod and its

paradigmaticmeaning for the technological sublime, see Christian Begemann, Furcht und Angst im Prozef der

des 18. Jahrhunderts(Fearand the Enlightenment: On literaAufklirung:Zur Literaturund Bewuf'tseinsgeschichte

ture and the history of consciousness in the 18th century) (Frankfurtam Main, 1987), 89-96; I. BernardCohen,

Benjamin FranklinsScience(Cambridge, Mass., 1990), 66-109; and Willem Hackmann, "Lightning Rods and

Model Experiments:Franklin'sScience Comes of Age," Studiesin Historyand Philosophyof Science,22 (Winter

1991), 679-84.

The Sublimeandthe ElectricChair

903

In the courseof the nineteenthcentury,the conceptof the sublimeshifted;manbecamethe majortriggersof the sublime.Technomadecreationsandachievements

thequalitiesnecesand

incorporated

logicaldevices,machines, buildingsincreasingly

Theywereso large,so complex,andso dynamic

saryto createa sublimeexperience.

thatthey seemedto be embodimentsof supernatural

power;at the sametime, they

werecreatedby mankind.Theysignifiedan almostsupernatural

abilityto overcome

the

the

forces

of

nature.

and subjugate

Moreover, technologicalworldwas understoodas the signof a divinemission,for God hadblessedoccidentalhumanitywith

in the forcesof nature,to penetratethoserevethe abilityto recognizehis revelations

take

of

them.6

and

to

lations,

possession

TheAmericancontinentofferedan idealterrainforthe creationof sublimeexperiencesin generaland specificallythe so-calledtechnologicalsublime.Fromthe very

firstexplorations

of the continent,descriptions

andreportsshowedthatnowheredid

natureseemmoreexcitingand at the sametime morefrighteningthanin the New

World.Yet, until the late eighteenthcentury,only the educatedelite consciously

with naturein orderto experiencethe sublime.Formen such

soughtconfrontations

as ThomasJeffersonorJohnQuincyAdams,the NaturalBridgein VirginiaandNiagaraFallswere wondersof natureembodyingdivine greatnessand signifyinga

in his Noteson the

uniquealliancebetweenAmericaandtheAlmighty.Nevertheless,

Stateof Virginia,ThomasJeffersonexpressedastonishmentthat even peoplewho

livednearthe NaturalBridgeneveror only rarelyvisitedit in orderto be awedby it.

It was only in the nineteenthcenturythatthe Americanwondersof naturebecame

to placessuchas the 215-foot-tallnatintenselyattractiveto manypeople.Traveling

uralstonearchin Virginiaor to NiagaraFallsacquiredthe character

of a pilgrimage.7

Fromthe 1820s on, the technologicalwondersof Americancivilizationsuch as

canals,bridges,andtrainscausedwavesof excitement.To contemporaries

theyrepresented the abilityof Americancultureto shape nature'sextraordinary

power,to

enablevastnumbersof peopleto travellong distances,andto speedup the advance

of civilization.Eventhe lastremnantsof the staticawearousedby the sheeromnipotence of natureand the size and powerof its wondersgaveway to faithin human

The Americanpoliticianand naturalexplorerGeorge

intelligenceand achievement.

PerkinsMarshstatedin 1860 in the ChristianExaminerthat the "sublimeconceptionsof extendedspace,of prolongedduration,of rapidmotion,of multipliednuminto a

bers,and of earthlygrandeurand beautyand power"had been transformed

of

"our

mental

constitution"

modern

science

and

technolpermanentcomponent

by

dictatesis the law of all lower

ogy. Marshcontendedthat "obedienceto [nature's]

tribesof animatedbeing,[but]it is by rebellionagainsthercommandsandthe final

of herforcesalonethatmancanachievethe noblerendsof his creation."

subjugation

In Marsh's

of nature"wasthe decisivedifferencebetween"the

eyes,this "subjugation

6

Klaus Bartels, "Oberdas Technisch-Erhabene"(On the technological sublime), in Erhabene,ed. Pries, 295Sublime.

316; Leo Marx, TheMachine in the Garden(New York, 1965), 197; Nye, AmericanTechnological

7 Thomas

Jefferson, Notes on the State of Virginia, ed. Thomas P. Abernathy (1785; New York, 1964), 17;

Howard Mumford Jones, O StrangeNew World(New York, 1967); Nye, AmericanTechnological

Sublime,2-3, 1920, 24-43; ElizabethMcKinsey,NiagaraFalls:Icon of theAmericanSublime(New York, 1985), 30-32.

904

The Journalof AmericanHistory

December2002

human and the brute creation... and the extent of [man's]victoriesover Nature is a

measurenot only of his civilization,but of his progressin the highest walks of moral

and intellectuallife." It was consideredan expressionof divine intentions, because

the Lordhad blessedoccidentalman with the magnificentability to createa technologicallyperfectworld. Even at Niagara,in the middle of the nineteenth century,the

fascinationshifted from the naturalspectacle to its technological appropriation,as

shown by ElizabethMcKinseyin her study of Niagaraas the "icon of the American

sublime."Approximatelysixty thousand visitors annually traveled to the falls by

train; they were attractedno longer only by the incrediblewaterfallsbut also by a

bridgeover the riverthat demonstratedthe triumph of the engineerover natureand

provoked an almost greatersensation of the sublime than did the falls themselves.

The bridgedemonstratedthat the power and largenessof naturein Americacould be

overcomeand subduedbecausethere existeda "correspondinglargenessand generosity of the spirit of the citizen,"as Walt Whitman announced in the introduction to

his 1855 Leaves of Grass.8

Electricityand the Sublime

Electricitywas a centralagent in the field of naturalforcesdestinedfor subjugationby

technologicalprogressand for the allegedperfectionof civilization.In the eighteenth

centuryJohn Wesleyreferredto electricityas "thesoul of the universe"becauseit had

a mysteriousstrengththat seemedto be an expressionof divine greatness.Membersof

the internationalscientific community declared the eighteenth century to be the

"electriccentury,"and researcherssuch as BenjaminFranklinand his colleagueswere

fascinatedby the immense power of the "electricalfire"that could be artificiallyproduced by means of a Leydenjar or silently drawnout of a thundercloudwith a long

pole or even a kite. Medical researchersrevitalizednumb limbs with the so-called

electricbalm, and novelistsspeculatedabout the life-givingforce of electricity.Mary

Shelley'sfamous scientist Victor Frankensteinignited "a sparkof being" in a previously lifeless body by means of the "glimmeringand seemingly ineffectuallight."A

strokeof lightning gavehim the power to breakthroughthe bounds of life and death

"andpour a torrentof light into our darkworld,"as Frankensteinphilosophized.9

8

George PerkinsMarsh, "The Study of Nature"(1860), in AmericanEnvironmentalism:TheFormativePeriod,

1860-1915, ed. Donald Worster (New York, 1973), 13-21, esp. 19, 14; Nye, American TechnologicalSublime,

33-34, 46-76. See also David E. Nye, "Republicanismand the ElectricalSublime,"ATQ, 4 (Sept. 1990), 185-99,

esp. 187-90; McKinsey, Niagara Falls, 253-56. For the dynamic qualities of the concept, see Wilson, American

Sublime, 5; and Walt Whitman, Leavesof Grass:AuthoritativeTexts-Whitman on His Art-Criticism, ed. Sculley

Bradleyand Harold Blodgett (New York, 1973), 711-31, esp. 712.

9 John Wesley quoted in RichardRudolph and Scott Ridley, PowerStruggle:TheHundred-YearWaroverElectricity (New York, 1986), 23. On the early researchon electricity,see J. L . Heilbron, Electricityin the 17th and

18th Centuries:A StudyofEarlyModernPhysics(Berkeley,1979). "The electric century"is referredto in Johann G.

Schaffer,"Die ElectrischeMedicin oder die Kraftund Wirkung der Electricitatin dem menschlichen Korperund

dessen Krankheitenbesonders bey gelahmten Gliedern aus Vernunftgriindenerlautert und durch Erfahrungen

bestatiget"(Electric medicine, or power and effect of electricity on the human body and its malfunctions, espeArzt: Textezur Medizin im 18. Jahrhundert(The symcially in the case of paralysis)(1752), in Der sympathetische

pathetic physician:Writings on medicine in the 18th century), ed. Heinz Schott (Munich, 1998), 220. For the

relation of electricityand medicine, see the whole compilation of contemporarytexts ibid., 219-41; and Margaret

Rowbottom and Charles Susskind,Electricityand Medicine: TheHistoryof theirInteraction(San Francisco, 1984).

The Sublime and the ElectricChair

905

Mary Shelley's novel was originally published in 1818, and electricity remained a

mysterious force throughout the nineteenth century. In 1896, Harper' New Monthly

Magazine published a long article on electricity; the very first sentence posed the

question, "what is electricity?," and the response was, "that is a question no man can

yet fully answer." Nevertheless, in the course of the nineteenth century, the rising

control over this still inexplicable power was increasingly fascinating. In 1858 the

British physicist and natural philosopher Michael Faraday stressed that the divine

quality of electricity revealed itself in its following natural laws that had been established and put to use by man-which caused a very sublime sensation:

Electricityis often calledwonderful,beautiful;but it is so only in common with the

other forcesof nature.The beautyof electricityor of any other force is not that the

power is mysterious,and unexpected,touching everysense at unawaresin turn, but

that it is under law, and that the taught intellect can even now govern it largely.

The human mind is placed above, and not beneath it, and it is in such a point of

view that the mental education affordedby science is renderedsuper-eminentin

dignity, in practicalapplicationand utility; for by enabling the mind to apply the

naturalpower throughlaw, it conveys the gifts of God to man.

In 1860 George Perkins Marsh maintained that a smart and courageous researcher

such as Benjamin Franklin deserved more respect and praise than the powerful gods

and heroes in Greek mythology:

In the whole rangeof those mythologieswhich are built on the apotheosisof mortal heroes, or the deificationof the powersof spontaneousnature,in the cosmogonies of the ancient bards,in the warfareof Gods and the Titans, we find no such

theme for ode or anthem as the recent history of scientific researchand triumph

supplies in abundantprofusion. Which is fitter to be celebratedin immortalsong,

the fiction of a Jupiterlaunchingthe forkedlightning to avengea slight offeredto a

favoredmortal, or the true story of the sagephilosopher,who, by the aid of a child's

toy, forged fettersto chain the thunderbolt?10

Faraday and Marsh emphasized electricity's potential to shape and improve human

life. In the 1840s, the electromagnet, the telegraph, and the first electric engines were

invented, ensuring a permanent role for electric current in daily life. Effective use of

electricity increased in the 1870s, launching an epoch in which the historian Thomas

P. Hughes locates "the American genesis." In this period, according to Edward Byrn's

1896 article, the United States was seized by a

gigantic tidal wave of human ingenuity and resource,so stupendous in its magnitude, so complex in its diversity,so profound in its thought, so fruitful in its

wealth, so beneficent in its resultsthat the mind is strainedand embarrassedin its

effort to expandto a full appreciationof it.

Benjamin Franklin, "Opinions and Conjectures, concerning the Propertiesand Effects of the electrical Matter,

arising from Experimentsand Observations, made at Philadelphia"(1749), in BenjaminFranklinsExperiments:A

New Edition of FranklinsExperimentsand Observationson Electricity,ed. I. Bernard Cohen (Cambridge, Mass.,

1941), 213-40, esp. 221-22; Cohen, BenjaminFranklinsScience,66-109. Mary Shelley,Frankensteinor theModem Prometheus(1818; Cologne, 1995), 47-48.

10R. R. Bowker, "GreatAmerican Industries:

Electricity,"HarpersNew MonthlyMagazine (Oct. 1896), 71039, esp. 710. Michael Faraday,"Notes for a FridayDiscourse at the Royal Institution"(1858), in BenjaminFranklins Experiments,ed. Cohen, epigraphfacing copyright page. Marsh, "Studyof Nature," 19.

906

The Journalof AmericanHistory

December2002

As Byrn emphasized,"The old world of creationis, that God breathedinto the clay

the breathof life. In the new world of invention mind has breathedinto matter,and

a new and expanding creation unfolds itself. . .. He [man] has touched it [matter]

with the divine breathof thought and made a new world."'1

In particularthe transformationof electricalenergy into light caused a sensation.

Just like a thunderboltcoming from the clouds, an initially invisible electric power

produced a clearlyvisible effect. The differencewas that electric light was made by

and under the control of mankind. In the 1870s and 1880s, light shows fascinated

the public. Enormousarclampsbathedthe centralsquaresof numerouscities in glaring light. In Wabash, Indiana, or Cleveland, Ohio, in Philadelphia,Boston, San

Francisco,or New York, contemporaryreports of arc light demonstrationsdraw a

uniform picture. When the large, strangelamps that seemed almost as powerful as

the sun turned darknessinto bright and shining light, the spectatorswere overwhelmed with awe and fell on their knees; "manywere dumb with amazement,"as

the WabashPlain Dealerdescribedsuch an event in 1880.12

It was no longer God alone who gave the world light; the awe and worship that

had once been devoted exclusivelyto the deity and its representationin naturewere

now given to man-made technology. In the following years, the electrificationof

public spaces spoke of a city's prestige and status. Thomas Edison's 1879 filament

light bulb played a crucialrole in the spreadingof the "electriclight" phenomenon.

The opening of the first power station, on New York'sPearl Street, in September

1882 is considereda turningpoint in the historyof electricityand artificialillumination. Its steam-drivendynamosproduceddirectcurrent(DC). With the power station

and the bulb, the lights were turned on in New Yorks financialdistrict, and by the

middle of the decade electric streetlightswere commonplace in largerAmericancities. The alternatingcurrentpropagatedby GeorgeWestinghousemade the transferof

high-voltageelectricityover long distancespossible and cost-effective,and the vision

of the electrificationof Americacould become reality.In 1896, generatorsat Niagara

Falls,using water power,began to produce the alternatingcurrent(Ac)that powered

the lights in Buffalo and set the Buffalo Street Railwayin motion. In the following

years, the corridorsand galleriesof the Niagara Falls Power Station became a more

awe-inspiringattractionthan the bridgeover the riveror the falls themselves.Only in

September 1907 did the naturalwonder of the waterfallsattractnational attention

again-when they were illuminatedby artificiallights at night.13

The importanceof electricityproduction and use to the concept of an advanced,

superiorsociety was manifestedby various exhibitions around the turn of the cen11

Byrn, "Progressof Invention during the Past Fifty Years,"82. Thomas P. Hughes, AmericanGenesis:A CenEnthusiasm,1870-1970 (New York, 1989). Hughes cites parts of Byrn'sarticle

tury of Inventionand Technological

Der technologische

in the German edition of his book: Thomas P. Hughes, Die ErfindungAmerikas:

Aufitiegder USA

seit 1870 (Munich, 1991), 23.

12 The WabashPlain Dealer from

Februaryand April 1880 is quoted in David E. Nye, ElectrifyingAmerica:

Social Meanings of a New Technology,1880-1940 (Cambridge, Mass., 1991), 2-3; referencesto similar reports

from other cities can be found in Rudolph and Ridley, PowerStruggle,24-27.

13

Nye, ElectrifjingAmerica, 58-59; Rudolph and Ridley, Power Struggle,28-29; Robert Friedel and Paul

Israel, EdisonsElectricLight: Biographyof an Invention (New Brunswick, 1986). Concerning the relationship of

direct and alternatingcurrent,see Andre Millard, "Thomas Edison, the Battle of the Systems, and the Persistence

The Sublimeandthe ElectricChair

907

tury.Electricityand in particularlight werestagedas visibleindicatorsof progress

and an auspiciousfuture.At the 1893 World'sColumbianExpositionin Chicago,

90,000 lightbulbsand 5,000 arclampsilluminatedthe fairgrounds,

poweredby the

largestpowerstationin the world,whichitselfcouldbe admiredin the Machinery

Hall of the exhibition.Ten thousandof thosebulbsflashedon the eighty-two-footthe biggestin the world,was the

tall EdisonTowerof Light;a giganticsearchlight,

Pan-American

later

at

the

of

the

tower.

Expositionin BufEightyears

crowningglory

falo, 240,000 bulbswereturnedon at dusk in a crescendoof brightness,and the

ElectricTowerroseto a heightof 391 feet.At the baseof the towerwasa modelof

sixtyfeet high.A sublimevisionof Americawith elecNiagaraFallsapproximately

tricityat its centerwaspresentedin Buffaloasit hadbeenin Chicago,andanelectric

streetcarcarriedthe visitorsfromone attractionto the next.In Chicago'sElectricity

of humancapabilitywereon display:electricheating,teleHall, true masterpieces

andwashingmachines,to nameonly a

for

phones long-distancecalls,dishwashers,

so-calledWhiteCity,"authentic"

fewexamples.In contrastto the exhibition's

villages

from other cultureswerepresentedon its Midway,and they werechronologically

arrangedto revealthe allegedsuperiorityof the "white"Americancivilizationdisyet skepticalHenry

playedin theWhiteCity.In thismanner,observedan impressed

Adams,the Chicagoworld'sfairseemedto marka leapin evolutionthatwouldhave

startledCharlesDarwin.The ChicagoTribunesaw in the fair an opportunityto

"descendthe spiralof evolution"and to trace"humanityin its highestphasesdown

almostto its animalisticorigins."Electricityandthe sublimewerewoventightlyinto

a discoursethatconstructeda beliefin racialandcivilizedsuperiority.14

The exhibitionspresentedmankind'sseeminglyboundlesspossibilities.Theypresentedelectriclight,machines,anddynamosas symbolsof science,civilization,and

a "longseriesof benefiongoingprogress.They embodiedto theircontemporaries

of life,as an articleon

centtriumphs"

of scienceovernatureandoverthe irregularity

in

the

North

American

Review.

The immeasurable

and

Life"

maintained

"Electricity

in

of

"for

of

been

the universe,waitthousands

had

hidden

years

strength electricity

New Monthly

man to literallyfind it out,"as Harper's

ing for nineteenth-century

in

October

1896.15

Magazineproclaimed

Althoughthis worldof machineswas createdby man, the apparentlyboundless

couldalsocausea bewildertechnologicalpotentialand the varietyof achievements

ing loss of orientationand intellectualconfusionamongcontemporaries.

Up to this

time, such a man as HenryAdamshad experiencedthat sort of confusiononly

throughconfrontationwith metaphysicalphenomena,as he himselfstated. For

of Direct Current,"MaterialHistoryReview(Ottawa), 36 (Fall 1991), 18-28. McKinsey,Niagara Falls, 257.

14Among the extensive literatureand referenceson the exhibitions, I referto Nye,

33-61;

ElectrifyingAmerica,

Gail Bederman,Manlinessand Civilization:A CulturalHistoryof Genderand Racein the UnitedStates,1880-1917

(Chicago, 1995), 31-41; Chicago Tribunecited ibid., 35; James Gilbert, PerfectCities: ChicagosUtopiasof 1893

(Chicago, 1991); Robert W. Rydell, All the Worldsa Fair: Visionsof Empireat AmericanInternationalExpositions,

1876-1916 (Chicago, 1984); John E. Findling, ed., HistoricalDictionary of WorldsFairs and Expositions,18511988 (Westport, 1990); and Henry Adams, TheEducationof HenryAdams (1907; New York, 1931), 331-45.

15 Edward P. Jackson, "Electricityand Life," North American Review, 153

(Sept. 1891), 378-79; Bowker,

"GreatAmerican Industries,"710.

The Journalof AmericanHistory

908

,

\

:SE

o

c

-

December2002

-

,_LF

- " i^611 4A

*-

^

OPERXATINO-ROOMN, F.[DISON STATION, INE' YOR)K.

trrl .

ivlrlu.

ult;t Ih,If.r?r.u: .I

Tre:,ty.i~"rr)i|llq:

w?. ilr,r,

: ,r

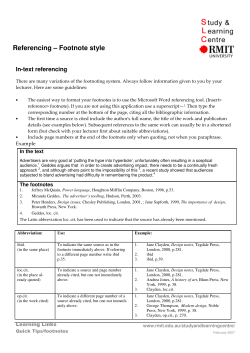

This Harpers New Monthly Magazine illustration features an enormously

powerful generator unit of New York'sEdison Station. The unit lighted

25,000 electric lamps and was operated by a single man. The machine

dwarfsthe operatorpictured in the foreground,transmittingthe idea of the

technological sublime to the magazine'sreaders. Reprintedfrom Harper's

New Monthly Magazine, Oct. 1896.

Adams, however, the unbelievably fast, precise, and noiselessly working electric

dynamo had metaphysicalqualitiesas well-it not only was a machine but appeared

to be an occult mechanism.As the embodiment of infinite energy,in Adams'seyes,

the dynamo was comparableto the Virgin Mary,whom he describedas the ultimate

The Sublimeandthe ElectricChair

909

symbolof reproductive

energyin the historyof mankindup to thatmoment:"She

wasgoddessbecauseof herforce;shewasanimateddynamo;shewasreproductionIn turn-of-the-century

the greatestandmostmysteriousof allenergies."16

America,it

thatwastheultimaterevelationof mystewasnot theVirginMary,butthegenerator,

the fertilityof both

riousenergy,as Adamsemphasized.The dynamorepresented

their

effects

on

human

life.

and

naturaland supernatural

Thus, the dynamo

power

was the archetypeof the technologicalsublime:it remainedincomprehensible

and

but it wasthe embodimentof the domesticated

naturalpowerthatelemetaphysical,

vatedhumanexistenceto a higherlevel.

The ElectricChair

At the end of the nineteenthcentury,electricityseemedto be underhumancontrol.

It producedclearlyvisibleandnoticeableeffectsandpromisedan inexorable

upswing

in the spiralof civilization.By meansof electricity,

mankindhadsucceededin bringing light into darkness,in producingheat throughpushinga button,in smoothly

crossingvastspaces,in multiplyingindustrialproduction,and in curing,regenerating, andstimulatinghumanbodies.Eventhe bodyitselfwasunderstoodanddefined

accordingto the latestparadigmsof researchin electricityand medicine.Whereas

researchers

hadenthusedaboutlivingin an electriccentury,coneighteenth-century

at

the

turn

of

the

nineteenthto the twentiethcenturiesphilosophized

temporaries

about an approaching"electricalmillennium."Partof this electricworld-manat the sametime-was the deadlydynamo.Amongthe elecmadeandoverpowering

tricalwonderson displayat the Chicagoworld'sfair,for instance,was an original

electricchairthat had previouslydone its mortalworkin Sing Singstateprisonin

New York.Visitorscouldadmireit in the midstof the sublimetechnological

presentationof the WhiteCity,whereasa guillotinewaspresentedon the Midway,among

otherhistoricalcuriositiesthathelpedvisitorsgraspthe evolutionary

historyof mankind.17

Formorethana century,the lethaleffectsof electriccurrenthad beenextraordihad

narilyfascinatingfor researchers.

BenjaminFranklinand his contemporaries

debatedthe possiblyfatalconsequences

of an electricshock,andtheyhadtestedthe

destructivepowerof electricityon animals.How greata shocka man couldendure

was a questionof burninginterest,and it was temptingto increasethe powerof a

batteryor to pool the powerof numerousbatteriesto find the answer.Researchers

reportedhavingexperiencedelectricshocksthemselvesas suddenand painlessand

not causingany visible sign of bodily harm or mutilation.BenjaminFranklin

knockeddownsix menwith the powerof two Leydenjars,andhis conclusionmust

16Adams, Educationof HenryAdams, 339-42, 381-83,

esp. 388.

On electricity and concepts of the body, see Martschukat,"'Death of Pain"';Tim Armstrong, Modernism,

and the Body:A CulturalStudy(Cambridge, Mass., 1998), 13-41; Rowbottom and Susskind,ElectricTechnology,

ity and Medicine, 163; Nye, ElectrifyingAmerica,153-64, 66; and, for the referenceto A. Sullivan, "ElectricalMillennium," Collier'sMagazine, Dec. 2, 1916, p. 44, see ibid. On the electric chair and the guillotine in Chicago, see

Gilbert, PerfectCities, 114, 119.

17

910

The Journalof AmericanHistory

December2002

be regardedas almost visionary:"Toogreata chargemight, indeed, kill a man.... It

would certainly,as you observe,be the easiestof all deaths."'8

In Franklin'sdays, "theeasiestof all deaths"was a highly debatedtopic, especially

in the discourses of medicine and law-two fields that in the following decades

would play a major role in the shaping of the concept of civilization. The age of

rationality, empathy, and civilization beginning in the late eighteenth century

spurredcallsfor a changein the executionof the death penalty.The performanceof a

slow and agonizing"riteof execution"on the scaffolddid not seem appropriatefor an

enlightenedsociety that understooditself as being rationaland humanistic.Nonetheless, only a few political theoristsand law expertsin North Americaor Europewere

of the opinion that the death penalty should be totally abolished.The new cultural

and political paradigmsrequireda transformationof the execution procedure,however; the defendant'slife should be taken as quickly and as painlesslyand even as

invisibly as possible. On the west Europeancontinent, this change of concepts was

embodied in the swift mechanizedbeheadingof the guillotine. In England and the

United States, hanging remainedthe preferredmeans of execution, but the performance at the gallowswas more and more de-ritualized.19

The debate about the most appropriatemeans and ritual of execution never

ceased. Startingin the mid-1830s, Pennsylvania,New York,and the New England

states moved execution sites behind prison walls. In the late 1860s, criticismof executions increasedagain, focusing now on the physical suffering of the defendants.

Bodily pain was consideredthe worst evil, and a civilized society had to combat it;

the North AmericanReviewmaintained in 1849 that "the man who maintains that

pain is no evil, is regardedsimply as a madman."In 1846, etherhad been introduced

into surgeryas an anesthetic.20

Referringto the death penalty in 1869, the writer Edmund Clarence Stedman

emphasizedthat death alone, and not physical torment, had to be the punishment

and that any prolongationof the throesof death should be deemed cruel and unnecessary.Accordingto Stedman,a slow execution did not comport with the tenets of a

18

Benjamin Franklin,"LetterXVII" (1755), in BenjaminFranklinsExperiments,ed. Cohen, 331-38, esp. 336;

see also the appendix to Benjamin Franklin,"ElectricalExperimentswith an Attempt to Account for their Several

Phaenomena"(1753), ibid., 300-301; and Benjamin Franklin,"LetterIII" (1747), ibid., 181. On self and animal

experiments, see Franklin, "Opinions and Conjectures, concerning the Propertiesand Effects of the electrical

Matter,"222. A cat killed in an electric experiment did not revealany mutilations of the body apart from minor

burns at the point of contact, accordingto Joseph Priestley,"Geschichteund gegenwartigerZustand der Elektricitit, nebst eigenthiimlichenVersuchen,"translatedinto German 1772 ("The History and PresentState of ElectricArzt, ed. Schott, 225-26.

ity, with Original Experiments,"original English edition 1767), in Sympathetische

19On the United States, see Louis P. Masur, Rites Execution:

of

of

CapitalPunishmentand the Transformation

in Nordamerika,11AmericanCulture,1776-1865 (New York, 1991); and Martschukat,Geschichteder Todesstrafe

65. On England, see, for example, V. A. C. Gatrell, The Hanging Tree:Executionand the EnglishPeople, 17701868 (New York, 1994), 45-55. On continental Europe, see Michel Foucault, Disciplineand Punish: The Birth of

the Prison, trans. Alan Sheridan (New York, 1977); Jiirgen Martschukat,InszeniertesToten:Eine Geschichteder

vom 17. bis zum 19. Jahrhundert(Performancesof execution:A history of capital punishment from the

Todesstrafe

17th to the 19th centuries) (Cologne, 2000); and Richard Evans, Rituals of Retribution:Capital Punishmentin

Germany,1600-1987 (New York, 1996).

20

See the review of A Treatiseon Etherizationin Childbirthby Walter Channing, North AmericanReview,68

(April 1849), 300-314, esp. 300. On the age of anesthesia,see David B. Morris, The Cultureof Pain (Berkeley,

and Anesthesiain Nineteenth-Cen1993), 57-78; Martin S. Pernick,A Calculusof Suffering:Pain, Professionalism,

turyAmerica(New York, 1985); and Martschukat,"'Death of Pain."'

The Sublimeandthe ElectricChair

911

civilizedsocietyand-combined with changingperceptionsof painandsufferingseemedto contradictthe EighthAmendmentof the Constitution,which forbids

Muchtoo often,an instantandpainlessdeathat the

cruelandunusualpunishments.

rope causedby a quick breakof the neck remainedwishful thinking.Stedman

stressedthatin morethanhalfthe casesdeathoccurredonly aftera long struggleby

slowsuffocation.Furthermore,

sometimesthe lengthof the ropeandthusthe height

of the fallwerenot correctlycalculatedaccordingto thedefendant's

bodyweight,and

the headwastornoff duringthe execution.Suchtormentsandunsightlysceneswere

advancedsociety,

incompatiblewith the self-imageof a civilizedandtechnologically

andtheywerean obstacleto culturalperfection.A solutionhadto be foundto represent the adequateprogressin civilization,and in PutnamsMagazineStedman

with new scientificknowledge,a painlessmode

expressedthe visionthat"doubtless,

of killingmaybe discovered,-asby an electricshockor somedeadlyanaesthetic."21

In the 1870sandthe 1880s,thepressofferedmoregruesomeanddetaileddescriptionsof hangingsthanever,andit alsodemandeda searchfornewmethodsof execution thatwouldcausea quick,clean,andnon-disfiguring

death.At the sametime,a

new type of accidentprovedthatsuch a deathcouldobviouslybe achieved.Power

stationsandpowerlineshadmultiplied,andthe numberof fatalaccidents-particuIn two years

larlyin the urbancentersof the Northeast-had increasedaccordingly.

in New YorkStatealone,overninetydeathsfromdirectcontactwithelectricalinstallationswere reported.The suddennessand the apparentpainlessnessof dying by

electricitymadean impression.Death as such had lost none of its fascinatingand

but electricitypromgruesomequalities,for it stillmeant"theend of all existence,"

isedto reducethe momentof dyingto a splitsecondandto stripdeathof its supposIn the guiseof electrifiedcivilization,deathcouldoccur

edlyarchaiccharacteristics.

withoutbeingassociated

withstruggle,sorrow,andbodilydestruction,as ElbridgeT.

a

New

York

and majorproponentof electricexecuGerry,

lawyer,philanthropist,

tions, emphasizedin 1889 in the NorthAmericanReview.Commentingon the

he noted:

increasingaccidentalelectrocutions,

In everycasethe actionof the currentwasso instantaneous

as to leavenot the

of a doubtthatdeathwasliterally

shadow

thanthought.

Thebodywasnot

quicker

therewereno indications

of anydeath-struggle;

noneof physical

mutilated;

pain.22

The advancedtechnologicalcapabilityof civilizedmankindseemedto open up a

path towardthe perfectionof the deathpenalty.In an age of seeminglylimitless

humaningenuityand invention,the taskof constructinga reliableelectricmachine

for the allegedlyperfectandpainlessexecutionof the deathpenaltywasconsidered

an execution

simpleandeasyto solve.Technological

progresspromisedto transform

21

Edmund ClarenceStedman, "The Gallows in America"(1869), in VoicesagainstDeath:AmericanOpposition

to Capital Punishment,1787-1975, ed. Philip E. Mackey (New York, 1976), 131-40, esp. 139; see also Gilroy

Keating, "CapitalPunishment,"NorthAmericanReview,147 (Aug. 1888), 235-36; and ElbridgeT. Gerry,"Capital Punishment by Electricity,"NorthAmericanReview,149 (Sept. 1889), 321-25.

22 On the

press reports,see Madow, "ForbiddenSpectacle,"487, 529-30; and Brandon, ElectricChair,25-46.

Gerry,"CapitalPunishment by Electricity,"324; see also Thomas A. Edison, "The Dangers of ElectricLightning,"

NorthAmericanReview,149 (Nov. 1889), 625-34. On Gerry,see Brandon,ElectricChair,52-53.

TheJournalof AmericanHistory

912

December2002

froma representation

of an archaicdesireandlongingforviolenceandcrueltyinto a

performancesignifyingadvancement,perfection,and sublimity.An artificially

induceddeaththatoccurredquickerthanthoughtandcausedneitherpainnormutiIn contemporary

lation-that wasthe promiseof electricity.

perception,suchan executionwouldenhancehumancivilization,andthus,evenas a destructive

anddeadly

force,electricitywouldfurtherunfoldits constructive

potential.23

Expertson electricityfostereda politicaldebateon the use of electriccurrentfor

executionsin the stateof New York.The electricians'

explanationseven impressed

New YorkgovernorDavidB. Hill who in his annualmessagein January1885 called

for a commissionof expertsto scrutinizethe best meansof execution.Established

the commissionconsistedof ElbridgeT. Gerry,a lawexpertnamed

shortlythereafter,

MatthewHale,and a dentistnamedAlfredP.Southwick.Afterthreeyearsof work

and consultationwith morethan two hundredexpertsespeciallyin medicineand

presentedthe hundred-page

technology,the commissioners

Reportof theCommission

Methodof Carrying

intoEffect

toInvestigate

andReporttheMostHumaneandPractical

in

The

New

York

Death

Cases.

reacted

to

theSentence

enthusiastically

press

of

Capital

to

the

to

and

"the

electric

the publicationof the commission's

analysis

proposal put

bolt in placeof the rope."In the eyesof the New YorkTimescommentator,

electricity

executionsinto anesthetic,painlessactsof mercy,furtherincreasing

wouldtransform

betweencivilizationandbarbarism.

Therewaseventalkabout"euthathe separation

Execution

becausedeathwouldbe "certain,swiftandpainless."

nasiaby electricity"

for

the

as

and

was

solemnity impressiveness

by electrocution perceived awe-inspiring

and not for its barbarous

of its performance,

cruelty.Accordingto the Times,New

Yorkwouldbe creditedfor beingthe firstcommunityin the world"tosubstitutea

methodof inflictingcapitalpunishment,andto set an examcivilizedfora barbarous

ple which is sureof beingfollowedthroughoutthe world."The novelistand critic

WilliamDeanHowellscommentedon the electricexecutionfrenzyin January1888

the collectivelyconstructive

andindividin a letterto Harper's

byjuxtaposing

Weekly

of

as

follows:

effects

destructive

electricity

ually

Thereis apparently

no reasonwhythismysterious

agentwhichnowunitesthe

whichilluminates

wholecivilized

worldbynervesof keenintelligence,

everyenterto heatthem,which

trainsof carsandpromises

propels

prisingcity,whichalready

to

shouldnotalsobeemployed

inexhaustible

hasaddedto lifeinapparently

variety,

take it away.24

andpainlessdeath"as a synThe commission's

reportpresentedan "instantaneous

an

of

and

as

civilization

for

and

expression the scientificapproachof a

onym

progress

23

Gerryelaborateson how easilyan electrickilling machine could be constructed:Gerry,"CapitalPunishment

by Electricity,"325. On the ambivalent conceptualizationof a humanitariansociety and the longing for the perception of violence, see Karen Halttunen, "Humanitarianismand the Pornographyof Pain in Anglo-American

Culture,"AmericanHistoricalReview, 100 (June 1995), 303-34; and Karen Halttunen, MurderMost Foul: The

Killerand theAmericanGothicImagination(Cambridge,Mass., 1998), 60-90.

24

ElbridgeT. Gerry,Matthew Hale, and Alfred P. Southwick, Reportof the Commissionto Investigateand Report

the MostHumaneand PracticalMethodof Carryinginto Effectthe Sentenceof Death in CapitalCases(Albany,1888).

New YorkTimes,Dec. 17, 1887, pp. 3, 4. William D. Howells, "Executionby Electricity,"Harpers WeeklyJan. 14,

1888, p. 23.

The Sublimeandthe ElectricChair

913

modernandadvancedsociety.Sincethe publicationof the report,this typeof "state

to quotea sarcasticnote by WilliamDean Howells,this "killingby

manslaughter,"

electricity[that]was almostthe sameas not killingat all"was calledfor in almost

everycommentand statementon the executionof the death penalty,and most

expertsagreedthat only an electricjolt could immediatelyand painlesslykill. As

statedin the commission's

report,electricitywasconsidered"themostpotentagent

knownfor the destructionof humanlife,"andthiscapacitywasprimarilyattributed

to the rapidityof its transmission.

Accordingto the commission,the guillotineand

the gunalsokilledquickly(thoughnot nearlyas quicklyaselectricity),yet thevisible

destructionof the bodiesand"theprofuseeffusionof bloodwhichit involves"

signified an archaicdesirefor violenceand cruelty,makingexecutionsby shootingand

The only alternative

methodto causedeathwithparticularly

beheadingintolerable.

out bloodshedandmutilationwaslethalinjection,whichwasopposedby the medicalprofessionbecauseof its closeassociationwith the practiceof medicine.25

Possiblythe only seriousalternativeto the electriccurrentwas still the rope,

becauseit was institutionallyand historicallyembeddedin Americancultureand

society.But the commissioners'

analysisof the gallowsas a primitiveinstrumentof

executionresembleda long anddetaileddiatribeagainstthe brutalandbarbaric

rituals of prehistorictimes.Accordingto the report,"suspending

the criminalby a cord

aroundhis neckfroma branchof a tree"wasthemostarchaicformof execution,and

the gallowswasdescribedas "theonlypieceof machinerythathasstoodstock-stillin

this eraof progress.Thereit stands,the sameclumsy,inefficient,inhumanthingit

waswhenit firstliftedits ghastlyframework

into the airof the darkages."It wasnot

that

the

described

accounts

of variousshockingscenesat the

"many

surprising

report

which

established

"a

widely

gallows,"

stronggeneralprejudiceamongculturaland

high-mindedpersons."The technologicallyadvancedand enhancedexecutionby

electricitywas consideredas a sharpcontrastto the rope.Accordingto the report,

mancouldovercomethe traditional

andalmostanthropologically

throughelectricity,

embedded"passionate

desireto inflictphysicalpainand suffering,eventhe utmost

on his enemies.Thatdesirecharacterized

"almostallprimitiveforms

agonypossible,"

of capitalpunishment,indeedthe remarkis trueof allearlyformsof punishments."26

It is particularly

noteworthythat the medicaland technologicalexpertswho had

beeninterviewedby the deathpenaltycommissionreactedto the deadlydynamoas

HenryAdamsreactedto the electricaldisplaysat the Columbianand otherexhibitionsaroundthe turnof the century.Amazedby humancapabilityandcaptivated

by

a technologically

sublimesensation,the expertspraisedthe powerof nature,which

was thoughtto havebeen absorbedand takenundercontrol,even thoughnone of

themknewexactlyhowelectricitykilled.Theywerecaptivated

by the "silentandinfinite force"of the dynamo.Thatwasevidentfromthe experts'elaborations

on death,

and

the

of

the

electric

transmission.

One

for

pain,

rapidity

expertexplained, instance,

that "anelectricdischargeoccursin one hundredthousandthof a second,or ten

25

William D. Howells, "StateManslaughter"(1904), in VoicesagainstDeath, ed. Mackey, 150-55, esp. 151.

Gerry,Hale, and Southwick, Reportof the Commission,75, 49.

26

Gerry,Hale, and Southwick, Reportof the Commission,33, 35, 55, 13.

The Journalof AmericanHistory

914

December2002

thousand times more rapidly than nerve transmission."The paralysisof the brain

would actuallyoccur in the very same moment as the electricshockwas initiated,and

the human being was expected to be "deadbefore the nerves can communicateany

sense of shock."As stated in the report,"anelectricshock of sufficientforce to produce death cannot in fact producea sensationwhich can be recognized"-it was considered impossible that pain could be felt. Moreover,the major criterion for the

significanceof a forcewas the influenceit exertedon human life-whether that force

was representedby the dynamo or the Virgin Mary.After all, the deadly dynamo

exerteda two-wayeffect on human existence:first,with incomprehensiblebut neverthelessmeasurableand human-generatedpower,the dynamocould take an individual

from life to death. Second, such an advancedexecution elevatedsociety to a higher

stateof civilization.Thus, the electricchairpromisedthat an advanceto a higherlevel

of technologicaland culturalperfectionon the evolutionaryspiralwould be achieved

at the moment of execution. Effortsto achievethis climb were consideredan obligation; the executioncommission maintained,"It is the duty of society to utilize for its

benefit the advantagesand facilitieswhich science has uncoveredto its view."27

As New York'sgovernorHill legalizedexecutionby electrocutionon June 4, 1888,

the enlightenedpublic celebrateda significantstep in the history of humanity.It was

said that the state of New Yorkwas the spearheadof civilizationand had left its mark

in the annals of humanity. One of the leading figuresin the technical implementation of the execution law was Harold P. Brown. He was working with Thomas Edison and had been in the electricitybusinesssince the first arc lights had been put up

in the 1870s. Brown published a hymn of praisefor electric execution in the North

AmericanReview.In his presentation,the electricalapparatusappearedas an occult

mechanismwhose infalliblydeadlypower unfolds at the push of a button and is displayed by magic instruments.Brown praisedthe incomprehensiblespeed as well as

the painlessnessand silence of the new method, even before it had been used for the

first time:

is in perfectorderand

indicatethatallthe apparatus

Dialsof electricalinstruments

closesthe switch.Respiraat everymoment.The deputy-sheriff

recordthe pressure

witha velocityequalingthatof

tion andheart-action

instantlycease,andelectricity,

a

life

at

before

nerve-sensation,

speed of only one hundredand

light, destroys

is a stiffeningof the muscles,

reach

the

brain.

There

can

feet

second,

per

eighty

relaxafterfivesecondshavepassed;butthereis no struggleandno

whichgradually

sound.The majestyof the lawhasbeenvindicated,but no physicalpainhasbeen

caused.-Suchis electricalexecution.28

From the summer of 1888 on, the press regularlypublished detailed reports on

experimentson animals that were sacrificed"on the altar of science."Readerswere

informedabout the exact type, size, and weight of the animals,the specific resistance

of their skin, and the strength and length of the electric shock to which they were

Adams, EducationofHenry Adams,381; Gerry,Hale, and Southwick, Reportof the Commission,75, 75, 75.

Harold P. Brown, "The New Instrument of Execution,"NorthAmericanReview,149 (Nov. 1889), 586-93,

esp. 593; see also New YorkTimes,June 5, 1888, pp. 2, 4. The text of the law is in Gerry, Hale, and Southwick,

Reportof the Commission,91-95. See also Howells, "Executionby Electricity,"23.

27

28

The Sublimeandthe ElectricChair

915

exposed.It was specificallyemphasizedthat afterthe execution-apartfrom being

lifeless-their bodieswerein perfectcondition.Therewas no doubt that in these

the "fatalcurrent"

provedto be the mostpotentforceknownto modern

experiments

to exhibit"superior

science;Westinghouse's

alternatingcurrentseemedparticularly

andwouldbe usedforthe firstexecution.The optimismwas

deathdealingqualities"

almostboundless,andhardlyanyonedoubtedthata man'slifewouldend by electrocutionat highvoltageafterfifteensecondsat most. Severalstatesconsideredfollowing New Yorksexampleby introducingnewexecutionlawsof theirown.29

"Kemmler

the First:Sentencedto Be Executedby Electricity"

wasthe headlineof

the New YorkTimeson May 15, 1889. Massiveenthusiasmspreadwhenthe twentyeight-year-old

vegetablepeddlerWilliamKemmlerfrom Buffalowas sentencedto

deathby electricshock,becausehe hadmurderedhis lover,TellieZiegler,with an ax.

behalf.George

Only the WestinghouseCompanytriedto interveneon Kemmler's

the

chief

was

the

advocate

forAC,which,

investor,

Westinghouse, company's

leading

in contrastto ThomasEdison'sdirectcurrent,wasmoreefficientandlessexpensive

but at thesametimewassaidto be moredangerousthanDC.Edison'slobbyhaddone

its best,andACwaschosenas the lethalweaponagainstcrimebecauseof its reputation asmorepowerful;it wasthusstigmatized

as too dangerous

forregularuse.Westand thereforeorganizedandpaidfor

inghousesawhis businessinterestsendangered

the bestdefenseteamKemmlercouldget. Kemmler's

lawyerscontendedthatelectric

executionwaspossiblycruelanddefinitelyunusual,andthereforeit wasunconstitutional.They even carriedthe caseto the SupremeCourt,and in the hearingsthey

claimedthatthe fataleffectof an electricshockwasnot certainat all.30

The pressaccusedthe Westinghouse

Company,Kemmler's

lawyer(BourkeCockand

his

witnesses

of

of

out

economic

self-interest

and of hinderingthe

ran),

acting

of

use of

progress civilizationand humanity.The contentionthat a knowledgeable

electricity,"properly

appliedfor the purposeof producingdeath,"did not leadto an

instantaneousand painless death was dismissedas devoid of all reason and

ridiculous"

froma scientificpointof view.To substantiate

thatclaimand

"supremely

underlinethe powerof electricity,

the concertedforceof naturewascalledupon,and

electriccurrentwasexplicitlydescribedas a formof lightningcontrolledby manthat

paralyzesthe brainbeforeit can feel any pain at all. Therefore,deathby electricity

was called100 percentpainless,and in the courtsnumerousexpertsconfirmedthe

statementin the commission's

report:"Thebrainhasabsolutelyno time to appreciate a senseof pain."CompetentWestinghouse

witnessesobjectedthat modernscience still knewtoo little aboutelectricityto makedefinitestatementsof thatkind;

finally,howelectricitykillswasstillunknown,a factthatevenThomasEdisonhadto

admit in the end. Still, the objectionwas dismissedas unpersuasive

and was not

29New YorkTimes,

July 31, 1888, p. 8; ibid., March 9, 1889, p. 5; see also ibid., Aug. 4, 1888, p. 8; ibid., Dec.

6, 1888, p. 5; ibid., Jan. 7, 1889, p. 5; ibid., Feb. 3, 1889, p. 3; and ibid., May 8, 1889, p. 4.

30

New YorkTimes,May 15, 1889, p. 3; ibid., July 12, 1889, p. 8. "In reKemmler,136 U.S. 436 (1890)," FindLaw <http:/laws.findlaw.com/us/136/436.html> (April27, 2001). For the conflict between Edison and Westinghouse, see Brandon, Electric Chair, 67-88; Millard, "Thomas Edison, the Battle of the Systems, and the

Persistenceof Direct Current";and Neustadter, "'Deadly Current,"'82-83. On the Supreme Court, see Denno,

"Is Electrocution an Unconstitutional Method of Execution?,"566-94.

916

The Journalof AmericanHistory

December2002

allowed to stand in the way of civilization and progress.Even if everybodyhad to

admit that "anymode of executionis liable to misadventures,[and] there is necessarily something experimentalin the first trial of a new mode of execution,"the probability of a failure of this experiment with William Kemmler was considered

"infinitesimal."A New YorkTimeseditorialremarkedon July 13, 1889: "In fact, the

whole contention seems too fantasticand unsubstantialto deserveserious consideration. Everybodyknows that electric currentsless powerful than it is proposed to

employ do kill men instantaneouslyand without pain."The courts agreed"thatit is

within easy reachof electricalscience at this day to so generateand apply to the person of the convict a currentof electricityof such known and sufficient force as certainly to produceinstantaneous,and thereforepainless,death."31

The defendant'slawyersfailed sufficientlyto deconstructthe belief in a sublime

perfection of mankind by a technologically progressive execution. After all, as

Schuyler S. Wheeler, an expert on electricitywho was also involved in the animal

testing, contended in Harper'sWeekly,electricity was still considered "mysterious,

but at the same time "thescienceborn a short time ago has furalmost supernatural,"

nished the possibilities for the arts of applied electricityat once so potent and so

novel that the world is carriedawaywith them."Wheeler emphasizedthat machines

poweredby electricityproduced"resultsstrangelyunlike everythingpreviouslyseen,"

and thus they appeared"almostmagical."Like Henry Adams, Wheeler showed his

fascinationwith the seeminglyboundlesspotential of the electricmotor. He stressed

that the dynamo provideda preciselydispensable,absolutelysilent, and clean power

suitablefor such diverseinstrumentsas sewing machines,trains,fire brigades,medical instruments,variousforms of illumination,and an execution machine.Alongside

descriptionsand sketchesof a jumbo magnet, an electric locomotive, and a motorized sewing machine, Wheeler's article included a detailed description and clear

sketch of the killing apparatus.Thus, Wheeler and Harper'sWeeklyexplicitlyembedded the electricchairin the spectrumof technologicalwondersthat enhancedhuman

existence. Moreover,that development was understood as an expressionof a transcendentalpower.32

Within this context, William Kemmler'simminent executionwas portrayedas the

most important experimentin the history of both electricityand the death penalty,

and Kemmlerhimselfwas considereda pioneer of science. The pressreportedmeticulously about the installationof electric chairs in the newly created death rows in

Sing Sing and Auburnprisons;Kemmlerwas to be executedat Auburn State Prison.

During the tests of the execution machine, light bulbs were arrangedon boardsthat

would control and display the force of the electric current.Furthermore,when the

lights "glowedbrilliantly"and "burnedbrightly,"they visualizedand aestheticizedthe

31 New York

Times,July 10, 1889, p. 4; ibid., Feb. 15, 1890, p. 3; ibid., July 13, 1889, p. 4; ibid., July 19,

1889, p. 4; ibid., July 13, 1889, p. 4; "In re Kemmler,136 U.S. 436 (1890)," FindLaw.See also New YorkTimes,

March 22, 1890, p. 4; ibid., July 11, 1889, p. 8; ibid., July 12, 1889, p. 8; ibid., July 16, 1889, p. 8; ibid., July 17,

1889, p. 8; ibid., July 25, 1889, p. 8; and ibid., July 26, 1889, p. 4. For furtherdetails, see Denno, "Is Electrocution an Unconstitutional Method of Execution?,"578-94.

32

Schuyler S. Wheeler, "Recent Developments of Electricity as an IndustrialArt," Harper'sWeekly,Feb. 25,

1888, pp. 141-44. For Wheeler'sparticipationin the tests, see New YorkTimes,Aug. 4, 1888, p. 8.

The Sublimeand the ElectricChair

917

Like various other inventions powered by electricity, such as a motor-run sewing

machine, a fire engine, or medical instruments, the execution machine picturedhere was

supposed to illustratethe advanced technology of the late nineteenth century. Reprinted

fiom Harper'sWeekly,Feb.25, 1888.

mysteriouspowerof the electricmachine.The brightlight emanatingfrom the

andthe public,becauseit sigtwenty-fourbulbssatisfiedthe executionprofessionals

naledthatthe machinewas "readyto receivethe murderer"-themarchof progress

andthe triumphalprocessionof the electricchairseemedunstoppable.33

Finally,on the eveningof August5, 1890, morethantwentyexpertsin the fields

of medicine,technology,and law gatheredin the Auburnprisonto see William

Kemmlerdie. At the gatesof the prison,an ever-increasing

massof peopleflocked

in

order

to

be

as

close

as

to

William

Kemmler's

deathand to "the

possible

together

climaxof thelongcontestthathasbeengoingon overthe beginningof electricalexecution."The crowddid not yell andmob the site, as theyhaddoneat publicexecutionson the gallows;rather,accordingto pressreports,theyremained"silent"

and"in

awe,"mirroringthe crowds'behaviorat the firstdisplaysof illumination:"Therewas

no noise.Therewas no loud talking,"recordeda journalist:"Everybody

spokein a

subduedwayas thougha feelingof awehadsettleduponthem."In the prison,each

of the expertswassurethatthe machinewouldmorethansatisfactorily

completeits

workand,moreover,thatKemmler's

would

be

to

the

annals

of mediadded

autopsy

calhistory.It wassaidthatthe wholeworldhadits eyeson Auburn,andhardlyanyone doubtedthat the triumphof electrocutionwould occur on the morningof

33On the lamps, see New YorkTimes,Dec. 29, 1889, p. 12; ibid., Dec. 31, 1889, p. 4; ibid., Aug. 2, 1890, p.

2; and ibid., Jan. 1, 1890, p. 5. For a clinically detailed reporton the setting up of the electric chairs,see ibid., Feb.

12, 1890, p. 9; ibid., Feb. 15, 1890, p. 3; and ibid., April 29, 1890, p. 8.

918

TheJournalof AmericanHistory

December2002

August 6. The vision of a clean use of violence in the name of the people was finally

expected to come true: "Death will take the place of life under conditions which

famous men of science have devised"-and what could possiblygo wrong?34

On August 7, readersmust have been stunned by the headline of the New York

Times:"FarWorse than Hanging: Kemmler'sDeath Proves an Awful Spectacle."

Terms such as "horror,""suffering,""disgust,"and "disgraceto civilization"dominated the first columns of the report on William Kemmler'sexecution. Against all

contemporaryreasonableexpectations,the fatal current,which had been praisedso

much, had to be turned on twice to accomplishKemmler'sdeath, and, accordingto

the press,the execution "wasso terriblethat the word fails to convey the idea."35

In the beginning, the procedurehad obviously gone accordingto plan. The witnessesawaitedthe imminent revelationin the executionchamber.Kemmleraccepted

his fate with stoic calmness,allowingthe preparationsto be completed,until he sat in

the chair in front of a semicircle of witnesses, "with the light from the window

streamingfull on his face,"to quote from the descriptionof the New YorkTimes.At

6:42 A.M. the electricitywas turned on for seventeenseconds, and afterwardsno one

doubted the death of the experimentalobject. But Kemmlerhad not died. The current had to be switchedon again;the carefullycontrolledsituationgaveway to chaos.

Kemmler'sdying did not contributeto a sublime sensationat all but invoked instead

the archaicfascinationwith horrifyingexperiences;accordingto the press, the witnesses, "horrifiedby the ghastlysight,"could not turn their eyes from the obviously

sufferingman in the agony of death. In the end, no one could tell for how many seconds or even minutes Kemmlerhad remaineda part of the electricalcircuit, since no

one had been able carefullyto control the procedureany more. The electricityflowed,

Kemmler'sblood vessels began to burst, the hair and skin under the electrodes

burned, "the stench was unbearable,"and people collapsed. "Kemmlerwas literally

roasted to death"-the demonstrationof humanitarianprogress,technologicalperfection, and an advancein civilizationseemed to have ended in shameand disgrace.36

On another,more analyticallevel of the reports,however,a differentpicturewas

presented.The evils of Kemmler'selectrocutionwere reduced to the visible part of

the performance.Experts of medicine and technology agreed that Kemmler must

have lost consciousnessalmost in the very moment when the button was pushedonly a hundredthof a second was said to have separatedthe final push and the end of

all sensation. Within that logic, though Kemmler had obviously been alive for a

while, he had felt no pain. If his body had shown signs of pain and suffering,it was

the sort of pain that could not be felt. The almost unbearableslowness and the torturous sight of his dying was explained away by the excitement and organizational

glitches of the event and by technicalproblemswith the machinery,including insufficient contact of the electrodesto the body and voltage that was much lower than

34New YorkTimes,

Aug. 6, 1890, p. 1; ibid., April 29, 1890, p. 8; ibid., Aug. 5, 1890, p. 1. For the gathering

of the crowd, see ibid., Aug. 7, 1890, pp. 1-2.

35Ibid.,

Aug. 7, 1890, p. 1.

36Ibid. Reportershad to rely on witnesses and on their imagination because the presswas excluded except for

two members of news agencies:see Madow, "ForbiddenSpectacle,"538-55. New YorkTimes,Aug. 7, 1890, p. 2.

The Sublimeandthe ElectricChair

919

planned.The intentionof avoidingthe associationof violence,cruelty,and barbarismwith the deathpenaltyin orderto ensureand performthe progressof civilization had not been fulfilled,but proponentsof electricexecutioninsistedthat the

victimhad not sufferedat all. The secretaryof the StateBoardof Healthof New

York,Dr. LouisBalch,wasone of numerousexpertswho assuredthat"fromthe first

shockthe prisonerwasvirtuallydead,sufferedno pain,and had no returnto consciousness."37

Somedetailsof the executionby electricityneededrefinement;

the validityof the

been

was

said

to

have

confirmed.

Under

bettercircumhowever,

different,

principle,

in

life

be

taken

a

flash.

the

in the

could

doubtless

commentator

stances,

Moreover,

New YorkTimesconjecturedthat,with a sufficientlyhighvoltage,Kemmler's

execution shouldhavebeendeclareda "wonderful

success."

To demandthe abandoningof

electricexecutionsand the returnto the gallowsas a consequenceof this eventwas

In a morecautiouscomment,the New YorkTridismissedas "absurd"

and"puerile."

bunestatedthat"theresultof the executionin referenceto the greatlyagitatedquestion as to the superiorhumanityof the newmethodoverhanging,is not conclusive."

Butskepticalinterpretations

of thissortwererarelygivenandwereoftencounterbalancedby the commentators

themselves.Dr. E. C. Spitzka,for example,an expertin

forensicmedicineandone of the physicianswho wereresponsible

for the execution,

at firstmaintainedthat "thedeathchairwill yet be the pulpitfromwhichthe doctrineof the abolitionof capitalpunishmentwill be preached."

he then

Nevertheless,

that

the

"emotional

side

of

our

nature"

was

arousedby William

emphasized

Kemmler's

execution,but froma rationalpoint of view,accordingto Spitzka,"the

heavingof [his]chestand abdomenareexplainedby the relaxationof the muscles,

and the consequentexpulsionof the air.It is absurdto say that he was not dead

[immediately].... The executionat Auburnaccomplishedits object."Still, most

commentators

weremoreemphaticandagreedwithAlfredSouthwick,a memberof

the executioncommission,who evennamedWilliamKemmler's

death"thegreatest

successof the age."Southwickemphasizedthat electricexecution"isa grandthing

anddestinedto becomethe systemof legaldeaththroughouttheworld."Thus,New

Yorkseemedto be aheadof the restof mankindandto havetakena largesteptoward

a perfectsociety.38

Elevenmonthslater,the pressannouncedthe approachof "thesecondexperiment"in electricexecution.This time, all safetymeasuresappearedto have been

of a state-ordered

deathpromisedto be "aperfectsuctaken,and the performance

cess."The arrangements

in generalandthe electricchairin particular

weredescribed

as a "perfectexecutionplant"thatwasunder"absolute

control."Therefore,the executionwould be carriedout with an "accuracy"

thatwas describedas "wonderful."

The beliefin the perfectedandprecisetechnologywasso boundlessthatin the early

37 Louis Balch

quoted in

38 Ibid.; New York

New YorkTimes,Aug. 7, 1890, pp. 1-2, 4.

Tribune,Aug. 7, 1890, p. 1; E. C. Spitzka quoted ibid., Aug. 8, 1890; Alfred Southwick

quoted in New YorkTimes,Aug. 7, 1890, pp. 1-2, 4. For referencesto similar reports in other newspapersand

magazines,see Neustadter, "'Deadly Current,"'84-85. The official report on the execution confirmed the idea of

William Kemmler'spainless death: New YorkTimes,Oct. 9, 1890, p. 4.

920

TheJournalof AmericanHistory

December2002

morning of July 7, 1891, four men were destined to die in Sing Sing state prison's

electricchair.This time the pressrejoicedafterwards;"theKemmlerbutchery"would

probablyremainthe only partial"failure"of the new method, and yesterday'sundertaking had been "entirely,emphaticallysuccessful"and "eminentlysatisfactory."The

immediatedeathsof the four men signifiedhuman control over the power of nature.

Eachwas "stonedead as quick as lightning,"one of the obviouslyimpressedwitnesses

remarkedbefore he left for a hearty breakfastwith a healthy appetite, accordingto

press reports.The execution of the four men had not only been the most humane

executionof all times but also the least gruesome.The new method, stressedthe physician Alphonse Rockwell,one of the most knowledgeableexpertson electricityand

its effectson the human body, "meetsall the requirementsfor killing decently,a man

sentencedto death."In the contemporaryperception,the fourfoldexecution in Sing

Sing marked a great step forwardin the history of mankind, and it illustratedthe

progress"in the art of killing by electricity,"as stated by Rockwell'scolleague,Alfred

Southwick.39

"Electricexecutionhas come to stay"was a majorprophecyof the following days. In

October 1891 the official reporton the executionsin Sing Sing indicated that in at

least two of the four cases signs of life had been registeredafter the first electric

shocks had been applied, but no generaldoubts about the complete success of the

project were raised. The immediate unconsciousnessof the four electrocutedmen

was naturallyassumed. Furthermore,electrocutionwas not at all discreditedin the

state of New Yorkwhen in December 1891 "scenesof horror"occurredduring the