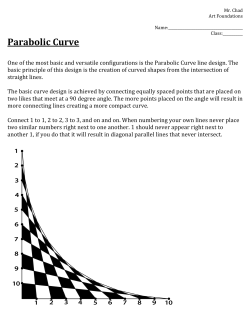

Excel Statistics Dan Remenyi