EDUCATIONAL COSTS AND FINANCIAL ANALYSIS

EDUCATIONAL COSTS AND

FINANCIAL ANALYSIS

J. B. Babalola

Department of Educational

Management, University of Ibadan,

Ibadan, Nigeria

Lecture One: Educational Cost Concepts

• Cost of education is a measure of what is given up in order to be

educated and/or to educate

• Educational costs can be expressed broadly as

– Opportunity cost or sacrifice and

– Money cost or expenditure outlay

• Opportunity cost represents the value of the real sacrifice

that have to be made in the process of receiving education

or in educating people

• Money cost or expenditure is the amount of money

directly spent on educational inputs or resources. Money

cost or expenditure can be classified as (1) capital [durable

inputs such as furniture, equipment and buildings] and (2)

recurrent [less durable inputs that can be used up within a

year such as salary of staff, subsidies to students and other

consumables]

•

•

•

•

Explicit cost versus implicit cost:

explicit cost involves open cash payment and issuance of a receipt; thus can be

expressed in a clear accounting statement.

Implicit cost does not involve open cash payment or issuance of receipt and

therefore, cannot be expressed in clear accounting statement

Incremental cost versus marginal cost:

incremental cost is the change in total cost of education as a result of the total

units of change in the scale of operation may it be expansion or contraction.

Only those costs associated with expansion or contraction is regarded as

incremental.

Marginal cost is the change in total cost associated with one-unit change in the

level of educational output

Sunk cost is fixed expense borne or to be borne as a result of a past mistake

regarding a contractual agreement or a present decision to change the level or the

nature of activity after we have committed some fixed expenses on the formal

plan.

Unit cost versus total cost:

– Unit cost is an average cost in which the total cost is divided by the number of

units benefiting from the total outlay. If students are the beneficiary, then the

total cost is divided by the number of students; if graduates, then divide by the

number of graduates; if staff, then divide by the number of staff; and if schools,

then divide by the number of schools.

– Total cost of education is a measure of the full monetary outlay and sacrifice

foregone in the process of being educated and/or educating people.

•

Depending on how it is measured, total cost is the addition of either:

–

–

–

•

•

•

direct and indirect costs,

fixed and variable costs, or

capital and recurrent costs

Direct cost versus indirect cost: [allocation vs. apportionment]

– direct cost can be easily allocated directly to different cost units in proportion

to the level of benefit accruable to each of the units involved, whereas,

– Indirect or joint cost cannot be easily allocated to different cost units in

proportion to the level of benefit accruable to each of the units involved.

Indirect cost can only be apportioned among various cost units on a pro-rata

basis

Fixed cost or variable cost: [level of change with operational change in short-run]

– fixed cost does not vary irrespective of change in the level of operation in the

short run. However, fixed cost can become variable when the capacity of the

fixed input is exhausted

– variable cost varies with the change in operational level in the short run

Capital cost versus recurrent cost: [based on the level of durability]

– capital cost is the expenditure incurred on durable resources or inputs with

long length of service, usually more than a year

– recurrent cost is the expenditure incurred on less-durable resources or inputs

with short length of service usually not more than a year

• Current price versus constant price:

– current price is the value of a resource as it appears in the book of account without

any adjustment to reflect the purchasing power of money;

– constant price is the unchanging value of a resource after adjustment of the book

value to reflect the purchasing power of money. During inflation, a trend in

expenditure expressed in current prices gives a wrong picture of the actual value of

money devoted to education over the period. Salary increased from N4000 in 1980

to N7000 in 1990. Given that the price index increased from 100 to 150 during the

period, then N7000 [current price] becomes (7000)100/150 = N4,666.67

• Private, institutional and social costs

– Private cost [direct and indirect] is borne by the individual students and their

families through expenditures on tuition fees, earning foregone, accommodation,

books, uniforms and transport

– Institutional cost [capital and recurrent] is borne by the provider through

expenditures on furniture, equipment, buildings, salaries of staff, subsidies to

students and other consumables

– Social cost is borne by the public through the government to cover all items under

private and institutional costs minus subsidies and tuition fees.

• Hidden cost versus transfer payment:

– Hidden cost appears as “free” real resources in form of men[such as voluntary

services] and materials that are usually concealed from analysts since they are not

paid for by any of the major decision makers.

– Transfer payment refers to movement of money [examples include scholarship and

pension] in trust from one pocket to another without any real expenditure from

the pocket to which the money is moved

Historical , standard and marginal costing

1.

Historical costing is a re-active process in which the following data are collected and

analyzed;

1. students (stock and flows),

2. staff strength and salaries,

3. capital and recurrent expenditures and

4. revenue from various sources

• The purpose of historical costing is to find out past cost behaviours regarding

1. item-by-item breakdown of the total cost,

2. cross and longitudinal analyses of unit cost,

3. Reasons or factors for variation in unit cost,

4. Investigation of economies of scale and cost-effectiveness study.

2. Standard costing is a pro-active process in which the expected or standard norms are

compared with actual data on

1. student,

2. staffing mix,

3. proportion of costs devoted to direct and indirect educational activities

4. and income modes.

• The purpose of standard costing is to

1. estimate cost deviations [positive or negative variance] from the norms,

2. Identify the reasons for variances and take corrective actions in form of

regulations.

3. stipulating appropriate measures for action

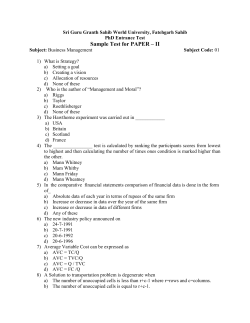

TABLE 1:

HISTORICAL COST STRUCTURE BY TYPE AND PURPOSE OF EXPENDITURE

Table 1: Classification of recurrent costs by type and purpose

Personnel cost

a. Teachers

b. Administrative staff

c. Other staff

Non-Personnel cost

a. Materials and supplies

b. Utilities

c. Miscellaneous

GENERAL

MAINTENANCE

HEALTH AND

SPORT

TRANSPORT

FOOD AND

DORMS

ADMIN

TYPE OR OBJECT

INSTRUCTION

PURPOSE [FUNCTION]

TABLE 2:

HISTORICAL COST STRUCTURE AT THE UNIVERSITY LEVEL

INCOME

GRANTS

1.

2.

3.

4.

Federal

State

Local

Private

INTERNALLY GENERATED REVENUE [IGR]

FEES

INVESTMENT

1.

2.

3.

4.

1.

2.

3.

4.

Undergraduate

Postgraduate

Overseas

Rooms/Board

GIFTS

1. Endowment

2. Donations

3. subscriptions

Rent

Payments

Interest

Profits

EXTERNAL AIDS

1. Loan

2. Grant

3. Technical

Assistance

BURSARY

EXPENDITURE

ON ESSENTIAL EDUCATIONAL FUNCTIONS

1.

2.

3.

4.

Direct teaching [Salary and goods]

Indirect teaching [Library, research]

Central administration

General administration

ON SUPPORTIVE FUNCTIONS

1. Works and maintenance [Salary & goods]

2.

3.

4.

5.

Health services

Estate and security

Student services

Retirement benefits

TABLE 3: AN EXAMPLE OF A STANDARD CAPITAL COST OF A PRIMARY SCHOOL

Standard criteria

Typical no of student places

Cost per student place

Land area (mean average)

Total building area (mean average)

Cost- Land and site survey

Cost- Site improvement and utilities

Cost- Construction materials

Cost- Construction labour

Cost- Construction cost per square meter

Cost- Equipment, furniture, etc.

Cost- total

Costs- Construction as percentage of total

Costs- Architects and other fees as % of Construction

Costs-Equipment and furniture as % of total

Costs: Land and site survey as % of total

Costs: Site improvement and utilities as % of total

Ideal

Actual

Deviation

CONCEPT AND CALCULATION OF MARGINAL COST

• Marginal costing provides information on whether or not to adjust [upward or

downward] educational services and how to adapt to changes over time.

• MC focuses on variable costs that are likely to change “as soon as” changes in

service take place, marginal costing begins by distinguishing between fixed and

variable costs of education. It also focuses on the length of time [short or long]

available for adjustment in service production since the degree of adaptation

will depend on the length of time considered for adjustment.

• The longer the time, the greater the possibility of making cost adjustment,

because most of the items classified as fixed in the short run will become

variable with time. At the institutional level, in the short run adjustments can

be made only in labour [salaries to staff and subsidies to students] and

material costs [expenditures on the consumable].

• a department can stop admitting students but cannot fold up business

immediately because time is required for liquidation [dispose off] of its fixed

factors [buildings, equipment and furniture]. Similarly, a contract teacher,

though a labour input, cannot be asked to go before the contract expires.

•

Cost analysts frequently ask: (1) how much of the total educational costs can be

varied immediately? (2) How much of the total costs cannot be varied until several

years later? (3) How soon and how fast will the variable costs change

ANSWERING THE FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS IN MARGINAL COSTING

• Total cost schedule and total cost function or curve are used to answer the

question of how much of the total cost can and cannot be varied immediately

• Average cost schedule and Cost functions or curves are used to answer the

question of how soon and how fast the variable cost will change as well as

how financially wise to change the enrolment level

• The three diagnostic levels are:

1.

2.

3.

Analysis of trend in total costs into fixed and variable elements in tabular and

graphical forms. Using the trend in total unit produced (Q)and the

corresponding total cost (TC], the analyst can then estimate the trend in

marginal cost (MC)using “MC“= {TCn-1 – TC n ]/[Qn-1-Qn]}

From a table showing the total unit produced and the corresponding total cost

broken down into fixed and variable aspects, the analyst can carry out the

analysis of the resultant average costs in tabular and graphical forms showing

the average total cost, average fixed cost and average variable cost. The last

column of the average cost schedule usually shows the marginal cost

The last diagnostic level is to establish the relationship between each of the

average costs on one side and the marginal cost. This analysis usually start

from the evaluation of the marginal cost using the first derivative of total cost

such that MC= δTC/ δQ, given that TC = ƒ{Q}. From this differential equation

the analyst can estimate (a) the optimum enrolment [Q] that will result in (i)

minimum average total cost [ATC] on one side and especially in (ii) average

variable cost [AVC] on the other side; the idea is that MC intercepts AVC and

ATC at their minimum or turning points (b) given Q the analyst can estimate the

MC and the AVC to see the undesirable event in which MC exceeds AVC

LEVELS OF MARGINAL COSTING

Marginal costing involves the following three levels

of analysis:

1. Total cost analysis

2. Average cost analysis

3. Marginal cost analysis

a) Derivation of marginal cost from differentiating the

total cost function with respect to the enrolment

b) Determination of the relationship between marginal

cost on one side and total cost as well as average

variable cost on the other to know the cost

implication of expansion or contraction in the level

of production

Table 1; Analysis of Total Cost by Adding Total Fixed Cost with Total Variable Cost

Enrolment

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

Total Fixed

Total Variable

Cost

Cost

1000

0

1000

200

1000

1000

1000

1000

1000

1000

1000

367

510

677

877

1127

1460

2460

Total Cost

1000

1200

1367

1510

1677

1877

2127

2426

3460

TOTAL COST CURVES

4000

AMOUNT IN NAIRA

3000

2000

1000

0

TFC

TVC

TC

0

1000

0

1000

1

1000

200

1200

2

1000

367

1367

3

1000

510

1510

4

1000

677

1677

5

1000

877

1877

6

1000

1127

2127

7

1000

1460

2460

Table 1; Analysis of Average Costs and Marginal Cost

Enrolment

Average Fixed

Cost

Average

Variable Cost

Average Total

Cost

Marginal Cost

0

-

0

-

-

1

1000

200

1200

200

2

500

184

684

167

3

333

170

503

143

4

250

169

419

167

5

200

175

375

200

6

167

188

355

250

7

143

208

251

333

8

125

307

432

1000

Notes: AFC declines as enrolment increases since same cost is spread over

more and more students (2) AVC declines at the beginning because some

variable costs are fixed initially. Beyond a point, AVC begins to increase as

some fixed variable costs defreeze with time (3) ATC declines at the

beginning and later increases. (4) AVC will reach its turning point earlier

than ATC

Chart Title

1400

1200

Axis Title

1000

800

Average

Variable Cost

600

Average Total

Cost

400

2001.

Notes:

b

the MC curve crosses ATC and AVC curvesMarginal

at their

Cost

a and (b) respectively. 2. When MC

lowest 0or turning points (a)

exceeds the1 AVC,2 the3cost4of adding

student

will

5

6 an extra

7

8

become increasingly more than cost of maintaining each of

the existing student

Mid-Semester Class Assignment 2013

1. Given that TC = 1000 + 10E - 0.9E2 + 0.04E3;

– Given that ΔTC/ΔE = MC ; find the enrolment that

results in minimum AVC

– Note that (a) TC = TFC + TVC, therefore, TVC = TC – TFC ;

(b) AVC = TVC/E then TVC = (AVC)(E); [c] MC = AVC = ATC

where enrolments result in minimum AVC and ATC

respectively

2. Given that:

i. ….MC = 10 – 1.8E + 0.12E2

ii. ….AVC = 10 – 0.9E + 0.04E2; Where E = enrolment rate

– Solve equations i and ii given that: E = 10, 11, 12, 13, 14

– From your results, recommend the optimum enrolment

and give reasons for your recommendation

Factors Influencing Costs of Education

• Cross-sectional vs. longitudinal cost analyses

– Cross-sectional cost analysis deals with observation of

variation in unit cost of education from place to place or

institution to institution at a particular time

– Longitudinal cost analysis deals with observation of

variation in unit cost of education in a particular institution

from one year to another year [2000-2010]

• Internal vs. external factors affecting unit cost

– Internal factors affecting variation in cost per student are

those causes that can be controlled by decision makers

– External factors affecting variation in unit cost of education

are those causes that cannot be controlled by decision

makers in education.

•

•

•

Internal factors affecting capital cost

– Location

– Importation

– Norms on space

– Curriculum design

– Style of building

Internal factors affecting recurrent salary cost [education is a labourintensive enterprise]

– Qualification mix

– Utilization [STR]

– Experience mix

– Enrolment [can be used to examine possibility of economies of scale]

– Number [staff]

Factors affecting recurrent non-salary cost such as maintenance , electricity bills and

other consumables are mainly external

– Aids from abroad

– Government policies

– Inflation

– Prices of goods

– Social demand or general demand

Second Mid Semester’s Test

• Briefly compare and contrast the following pair of

cost concepts as related to education:

1. Opportunity cost and expenditure

2. Explicit and implicit costs

3. Incremental and marginal costs

4. Total and unit costs

5. Direct and indirect costs

6. Fixed and variable costs

7. Capital and recurrent costs

8. Current and constant prizes

9. Private and institutional costs

10. Allocation and apportionment of costs

Each correct answer carries 0.5 [total = 10 marks]

PART TWO: FINANCIAL ANALYSIS

Methods of Financing Education Systems

• Centrally financed system • Locally financed system

– Central government bears

the burden

– Such education will be in

the exclusive legislative list.

Thus not a shared

responsibility

– Local governments only

provide and maintain

education

– Prone to financial pressure

– Can enhance uniformity

and equality of educational

opportunity

– Local government bears

the burden

– Such education will be in

the concurrent legislative

list. Thus a shared

responsibility

– Local governments

provide, finance and

maintain education

– Prone to political pressure

– Difficult to maintain

educational standards and

uniform opportunity

Methods of Financing Education Systems

Publicly financed system

•

•

1.

2.

3.

4.

Publicly financed education system

involves the use of tax revenue, often

supplemented by user charges.

Four conditions for public intervention in

education are as follows:

Joint consumption because such

education does not generate gains or

losses that can be assigned to any

particular individual

Equal consumption because such

education generates the same amount of

gain or loss to various recipients

“Ration-less” supply of such education

since no member of the community can

be denied entrance on the basis of

economic and other disabilities

Market failure exists since the forces of

supply and demand cannot determine

the price. Since those who have not paid

for education can get as much as those

who have paid, no motivation to pay

Privately financed system

Conditions for private involvement

• Income of the nation may reduce thus

necessitating fees, subsidy removal,

• Competition among sectors and within

education. Private sources supplement share

• Equity might lead to subsidy removal if subsidy

transfers resources to children of the rich

• Fiscal constraints on expansion makes it

impracticable to continue subsidization

• Revenue drive might become necessary

especially during budget cuts or introduction of

new programmes at the institutional level

• Incentive to be efficient might force the

government to subject public institutions to

competition by deregulating private education

• Social returns to education is expected to be

greater than private return to justify public

funding of education. When private returns are

higher than social returns, then there might be

need to introduce private contributions to

education.

What funding model is best to adopt?

PUBLIC FUNDING MODEL

PRIVATE FUNDING MODEL

Pure Public

Privatized public

Supported by

government

self financed,

non-profit

for profit

-solely

publicly

financed

[ especially

Teaching &

research]

With increasing

funding shortfall

[cost per student

fell $6300 in 1980

to $1241 in 1995 in

Africa]

Sponsored or

aided by

government

-controlled

tuition fees,

-Donations

-Foundations

contributions

To retain

autonomy,

remains

independent

HE companies

quoted on the

stock market

-withdraw of

subsidies

-IGR mobilized

-Cost sharing

introduced

-Request for public

accountability

-Cost measures

-diversification

-Commoditization

-Loan schemes

-Student s

are

subsidized

[to address

inadequate

high-level

manpower

demand and

inequity in

provision]

introduced to

help households

5/15/2015

Solusi & Anna

Malai

[Zimbabwe]

Daystar

[Kenya]

Foreign

Contributions

Foundation

donations

Tuition fees

Friends

donations

TRUSTAFRICA'S DIALOGUE

Specially, these

invest in the

intellectual

stock by paying

students costs

and mentoring

them for work

and life

allowing them

to pay later.

23

Funding Agencies [Spenders]

Public Agencies:

MOE, Education Authority

Federal/State/Local

Private Agencies:

Individuals/Parents/Relatives/

Companies/Communities

Voluntary Agencies, etc

External Agencies

Users of funds

Public

Educational

Institutions

Private

Educational

Institutions

Foreign

Educational

Institutions

Sources and Users of Educational Funds

Source: Akangbou [1987]

FLOW OF FUNDS FROM SPENDERS TO USERS

• Each of the funding agencies has direct link with each

user of funds. The presence of public agencies are

directed felt in public educational institutions, while the

presence of private agencies [individuals, parents,

relatives, companies, communities and voluntary

organizations are usually felt in private educational

institutions. The presence of foreign agencies are usually

felt in foreign educational institutions.

• Nevertheless, some presence of private and foreign

agencies can be felt in public educational institutions

• However, the presence of the public and foreign agencies

in private educational institutions is likely to be very

small because private institutions depend on fees and

very few scholarships are usually awarded by foreign

agencies to individuals studying in private institutions

BURDEN OF EDUCATIONAL FINANCE

• The burden of financing education amongst the

three groups of financiers may not be equal. The

burden will depend on the philosophy guiding the

provision of education in a particular geographical

region.

• In a free-education nation, the public sector is

expected to bear the largest share of educational

expenditure.

• In a fee-paying nation, the private sector will be

very active.

• External agencies participation usually declines

over time with the achievement of high level of

economic development in a nation

FLOW OF FUNDS FROM SPENDERS TO USERS

• Each of the funding agencies has direct link with each

user of funds. The presence of public agencies are

directed felt in public educational institutions, while the

presence of private agencies [individuals, parents,

relatives, companies, communities and voluntary

organizations are usually felt in private educational

institutions. The presence of foreign agencies are usually

felt in foreign educational institutions.

• Nevertheless, some presence of private and foreign

agencies can be felt in public educational institutions

• However, the presence of the public and foreign agencies

in private educational institutions is likely to be very

small because private institutions depend on fees and

very few scholarships are usually awarded by foreign

agencies to individuals studying in private institutions

BUDGET AND RESOURCE ALLOCATION IN EDUCATION

• An educational budget is a document outlining the systematic

scheme for raising and allocating resources for a given future

period in numerical and monetary terms.

• A budget is usually based on an educational operational plan.

The operational plan is usually for three years and the budget

is expected to cover only the first year of the plan.

• The first step after studying the operational plan is to

estimate the expenditures [recurrent and capital] that will be

made to achieve the desired objectives of the plan

• The last step is to prepared the revenue budget or the

estimate of the domestic resources that will be made

available to education during the budget year. The revenue

budget will take into consideration the amount of resources

that can be generated from public, private and foreign

agencies to education

• The three steps in budget preparation is known as the

triangle of budget [starting from analysis of the educational

plan to estimates of resource required and resource available]

Figure 1: Theory of Public Education Finance

Objectives of public finance

To provide funding to institutions so that all

students can learn effectively

Internal Process

Inputs

1. Instructional

conditions

2. Resource

situation

Fund mobilization

Allocation Mechanisms

Targeting Mechanisms

Expenditure Control

Outputs

Sufficiency

Equity

Efficiency

Outcomes

Quantity

Quality

FUNDING SOURCES AND FINANCING MECHANISMS

Public Stream

1.

2.

3.

4.

International

National

State

Local

Direct:

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

Block grant

Earmarked on specific revenue stream

Marching funds from public/public

Vouchers to providers or families

Subsidy of capital facilities;

Subsidy of curriculum development

Subsidy of quality assurance systems

Indirect:

1.

2.

3.

4.

Private Stream

1.

2.

3.

4.

Families

Community groups

Faith-based groups

Employers

Subsidies to parents

Top-up fee eligibility

Tax credits

Parental leave policies

Direct:

1. Payments of providers

Indirect:

1.

2.

3.

Volunteering or Lower wages

Donations to faith-based organizations

Time

30

How is education transformation funded? [ More Sourcing]

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

Public investment

private foundations

Bilateral aid agencies

multilateral aid agencies [Nelson Mandela Foundation]

Multinational in Africa [Shell Oil]

Philanthropic donations and alumni contributions

private providers [for profit and non-profit],

resource diversification through introduction or increases in tuition fees

[in conjunction with provision of scholarships and grants for the

disadvantaged students who merit higher education], and

research and consultancy incomes

other forms of income generation [investment activities].

loan schemes,

charging user fees,

elimination or reduction of less essential student benefits.

Double track

Entrepreneurialism

Information marketing

Innovation in management of funds to reduce cost

1/27/2011

INCOSHE 2011

31

Emerging Mechanisms for Ensuring Sustainable in HE

Conventional

Emerging

Welfare approach funding

Market approach funding

Public HIs

Mixed and private HIs

Public financing

Private financing and public –private partnership

Private state-financed HIs

Private self-financing HIs

Government recognized private HI

Self-recognized private HI

Degree-awarding private HIs

Non-degree awarding private HIs

Philanthropic /educational private HIs

Commercial/ for profit private HIs

No fees

Introduction of fees

Low levels of fess

High levels of fees

No student loan

High levels of fees

Ineffective not-for-profit loan programmes -no

security and high default rates, based on merit and

economic needs

Effective commercial loans-secured/mortgage with high

recovery rates, based on ability to pay or feasibility

Scholarly/academic curriculum

Self-financing, marketable, profitable curriculum

Formal/full-time HE

Open, distance, part-time HE –reduce building costs

Leader’s choice based on academic Leader’s choice based on funding

expertise

1/27/2011

INCOSHE 2011

32

Source: Sanyal & Martin [2006]

FINANCING FLOW CHART

No

Need

Assessment

Are there

problems

Yes

?

Monitoring &

evaluation

Yes

Implement

planned

programme

Additional

Resources

obtained

Are

resources

sufficient?

Additional

Required

Prepare

Project &

find

donors

No

Evaluate

resources

available

Source: Adapted from Udom [2002:437]

PROJECT CYCLE IN EDUCATION

evaluation

Implementation

and supervision

Negotiation

and approval

identification

preparation

appraisal

1. Identification: search for an idea with a development

potential

2. Preparation: begins with specification of the

objectives, targets to be achieved, the actions to be

performed and the responsible agents

3. Appraisal: sponsors review the proposal and it can be

accepted, modified or rejected

4. Negotiation and board approval: both spenders and

users of funds discuss and agree on the conditions for

success including drafting of the implementation

plans

5. Implementation and supervision: one funds are

available, we need to follow agreed procedures. The

financing bodies are to ensure compliance

6. Evaluation: at completion, the financing body

undertakes an independent evaluation to compare

actual with the expected results.

COST-BENEFIT ANALYSIS AS AN APPRAISALTOOL

• Cost-benefit analysis is an appraisal tool for

evaluating alternative allocations of resources to

different levels and type of education

• It attempts to describe, quantify and compare the

social/private costs and social/private benefits of

investment projects, thus, assisting sponsors to

decide whether or not an educational investing

should be undertaken

• Despite its political, human, identification and

measurement problems, cost-benefit analysis has

been widely used in education

• There is the prospect for continuous use of costbenefit analysis in determining investments choice

in education since efforts are on to eliminate its

glaring deficiencies.

STEPS IN COST-BENEFIT ANALYSIS IN EDUCATION

Identificatio

n of present

and future

effects

Quantificati

on of the

tangible

effects in

physical

term

Monetizatio

n of all

commensur

able effects

Aggregation

: Discounted

Cash Flow,

Rate of

Return,

Payback

Period, Size

of Unit

Sensitivity

analysis

Identification

Effects

[what

difference

will this

project

have?]

Present

Future

Change in

Efficiency

[output]

Change in Equity

[distribution]

Change in

employability

[earning]

Change in

enrolment [social

demand]

-ve

-ve

-ve

-ve

+ve

+ve

+ve

+ve

Quantification [in physical unit]

• Changes in output in goods resulting from a project

may be measured in kilogram per year for each year of

the project. Changes may be measured in number of

houses, kilometers of road constructed, number of

graduates produced, number of dropouts prevented,

number of repetitions prevented

• This quantification does not cover some effects such as

contribution to social harmony, democracy, aesthetic

or culture because these might be difficult to measure.

• Such intangible effects, while meriting description

within the cost-benefit study, necessarily remain

outside the quantitative aspect of economic analysis

Monetization [valuation]

• For an increase in output of so many kilograms of some

goods, a monetary value for the change in output is

developed.

• The economic rule governing the determination of

monetary values is the willingness to pay [WTP], which

refers to what society, if perfectly informed, will be willing

to pay to gain a benefit or to avoid a cost.

• Under perfect competition conditions, WTP reflects the

market prices. Under public goods and externalities

conditions, monetary values used are shadow prices

• Incommensurable effects [that are amenable to physical

quantification but not translatable to money] are often

left out at this stage

Aggregation

•

•

This is to reduce costs and benefits over the span [economic life] of the project to a

single summative number that captures the overall worth or desirability of an

investment project.

The most popular quantitative aggregation techniques are

– Discounted cash-flow

– Rate of Return

•

•

•

Internal rate of return

Benefit-cost ratio

Net present value

– Payback Period

– Proportional to Size of Unit

•

The qualitative methods include

– Necessity degree

– Executive judgment and experience

– Squeaky wheel principle

•

•

All quantitative aggregation schemes require discounting future costs and benefits,

that is, placing less weight on an effect the further into the future it is expected to

occur. The following discounting formula used

PVt = 1/(1 + d)1 →0; t →∞; current time is t = 0 so its weight [PV] is 1

The weight during the first year of project is 1 and all future years have weights less

than 1. For example, the weight for effects expected 20 years from now using a

discount rate of 10 percent is roughly 0.15. This means a N100 benefit 20 years from

now would be 0.15 multiplied by N100 or N15 this year

© Copyright 2026