2015 Issue 1

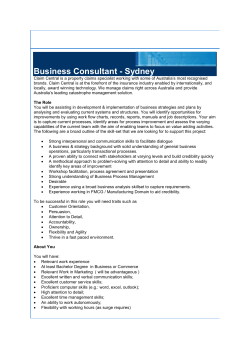

Ltd 2015 Issue 01 Newsletter Second quoll translocation to follow successful trail The trial reintroduction of Western Quoll to the Flinders Ranges National Park in South Australia has been judged a success on all counts. This means permission to bring in a second batch of western quolls has been granted. The Western Quoll Reintroduction Team is now planning for that exciting event, and a date in early May has been identified as ‘Q Day’. Forty-one Western Quoll were released around Wilpena Pound last April, the first of the species seen in the area in over 120 years. Until the relocation program, western quolls could only be found in the wild in the southwest corner of Western Australia, even though they once lived in every mainland state. The Foundation for Australia’s Most Endangered Species is raising $1.7 million to roll out one of the most important – and controversial – wildlife recovery plans in Australia today. Important because quolls are keystone predators and their presence contributes to the health of arid ecosystems. Controversial because bringing back locally extinct species to wild habitat is extremely rare, especially where feral predators are present. CEO Cheryl Hill said FAME was relieved and excited: “Even though we knew, based on 18 years’ work by the Western Australian Department of Parks and Wildlife supporting Australia’s last Western Quolls, that quolls can survive where cats are present, we did not know exactly what would happen in SA.” “As it turns out we’ve done better than we thought we would and now we have an effective action plan that can be shared with others who want to bring back the quoll to other parts of its former range. After 250 years of losing one species after another we’re turning the tide and I dare to hope that the future for wildlife is a little brighter, especially if our search to find an effective cat control device is successful.” The first quolls to arrive in the Flinders Ranges were electronically tracked both on the ground and from the air. Their radio collars were been progressively removed but the next batch will also be fitted with radio collars and tracked to monitor survival and health and to determine their behaviour when interacting with the established territories of earlier arrivals. The next batch of quolls will be chosen for youth and fitness, and will arrive just in time for mating season when last year’s young should be ready to join in. Western Quoll live around 3 years in the wild. They breed best in their first year, although many of last year’s females could also be capable of breeding again. Based on these results, and provided that survival rates continue to be good, the population of Western quoll in the Flinders Ranges could double or even triple very quickly. The program to restore the Western Quoll to the Flinders Ranges of South Australia will continue until 2018. Thanks to many generous donors we have funded the planning phase and the trial phase but we still have $1m to find to ensure that the project can go the distance and reach a successful conclusion. PLEASE send your generous contribution to FAME, PO Box 482 MITCHAM SA 5062 or online: www.fame.org.au/donate. If you know of others who are passionate about Australian wildlife and would be interested in supporting this important project please ask them to contact FAME CEO Cheryl Hill via [email protected] or phone 08 8374 1744. Photo courtesy Ecological Horizons. Photo courtesy Ecological Horizons. Photo courtesy Hannah Bannister. Top: Collaring a quoll is no easy task. Centre: Western Quolls use speed, teeth and escape routes in rugged terrain to survive predators. Bottom: These 2014 babies will be ready to breed when the next shipment of Western Quolls arrives in May. What’s Inside… •Children rally to support FAME •Farewell to the Mallee Emu-wren •Bramble Cay Melomys •Mahogany Glider •Feral Feature •KI leads the way Milla’s Story Milla has been learning about endangered species in primary school and she cares about keeping animals safe, especially endangered Australian animals like the Tasmanian Devil, the Mountain Pygmy Possum and the Western Quoll. Above: Nilla selling cards at her local Post Office. Inset: Nilla’s cards. Milla decided that just feeling sorry for these animals wasn’t enough. She wanted to do something to help. With the support of her parents Milla thought of a plan - and then she put her plan into action. The first step was to make some cards to sell. The second step was to find a place to sell the cards. It turned out that the local Australia Post office was also happy to help. They allowed Milla to set up a display of her cards right in the shop, and to stand there to talk to the customers about why they should help too. Milla attracted a lot of attention and many people were happy to buy her cards. Afterwards, she sent the money she raised to FAME and we are using it in support of our endangered species projects. Thank you Milla! Thanks to Australia Post, too. I’m sure there are now more people in your town who are interested in endangered wildlife because of your efforts and your kindness. South Australian schools fundraising to help restore the Western Quoll There are many children like Milla and Marshall who worry about endangered animals and want to do something but don’t know how. To help all those children, this year FAME has developed a school fundraising program that can be used for both primary and secondary students and will be of great benefit to both the students and the Western Quoll. Our program will provide information, learning activities and teacher’s notes for three age groups, and give-aways like badges and stickers. In return, we ask that the class or the school raise funds to help bring back the Western Quoll to its original territory, starting in the Flinders Ranges of South Australia. We plan to roll the program out right across the country, but this year we’re starting in South Australia. It’s important to remember that the Western Quoll once lived right across Australia, in every mainland state, but is now reduced to the south west of Western Australia. The first step in restoring the quoll to its original territory is being taken in South Australia, in the Flinders Ranges. The recent successful Page 2 trail reintroduction in 2014 means we can bring more quolls from WA in 2015 and 2016, provided we have the funds. The project in SA concludes in 2018, when we hope that a thriving population of quolls has been established in the Flinders Ranges and is beginning to spread out. If this happens we will know that the future of the Western Quoll is much more secure and we can turn our attention to other places and other states where this wonderful little animal once lived. And that exciting achievement will be thanks to every person, every organisation and every child, including Milla and Marshall and their parents, who cared enough to make the effort to help. HAVE YOU MADE A CONTRIBUTION TO THE FUTURE OF THE WESTERN QUOLL? Please join us by sending your donation for the Western Quoll Reintroduction Project to FAME via our website www.fame.org.au/support or post your donation to FAME at PO Box 432 MITCHAM SA 5062 Marshall’s Story Marshall is a 9-year-old student at Southern Montessori School in O’Sullivan Beach, South Australia. Marshall may be only 9, but he already understands that Australia’s wildlife is special and needs help. This is Marshall’s story: “One day in class last year the teachers handed out some flyers about FAME for the children to read and take home. The flyers had information about some of my favourite animals, like the Tasmanian Devils. I like helping animals and I wanted to help FAME. “I decided to start collecting bottles and cans so I could take them to a recycling centre for money and then send that to FAME. At school I did a presentation about the Tasmanian Devils and Devil Ark so other children would want to help too. I was really proud to read that the Tasmanian Devils got a giant freezer for food storage from everyone’s donations. “I’m looking forward to helping FAME and the animals with more recycling and donations this year.” We’re glad to have you as part of the team Marshall! Thanks for helping. Above: Marshall raising funds by recycling bottles and cans. Inset: Marshall is very proud of his FAME sticker. Editor’s Note: FAME helped found Devil Ark, and we have been contributing to the Ark and it’s precious population of devils ever since. In winter 2014 the freezer we funded (with Marshall’s help) once again proved its life-saving importance when heavy snow locked down the Ark. Roads were impassable, and staff had to rely not only on food stored in the freezer, but also on the cool room. Icy conditions at the Ark mean that the temperature is lower outside than inside, and when that happens the FAME cool room is the only place where food can be defrosted. Western Quoll and Brush-tailed Possum Re-introduction Timeline Quolls collected from south-western Western Australia Flown directly from WA to Wilpena Pound, wild-to-wild release program The Western Quolls are fitted with electronic collars. 40 Western Quolls to be released in May 2015 and again in 2016 Western Quoll breeding in June/July 2014 – at least 60 babies born 50-100 Brush-tailed Possums to be released into Wilpena Pound in July 2015 2018 OBJECTIVE: Western Quolls and Brush-tailed Possums established; feral predator control in place; natural systems begin to recover Page 3 April 2014 – 18 female Western Quolls released into Wilpena Pound April 2014 – 20 male Western Quolls released into Wilpena Pound Staff and PhD students are undertaking an extensive monitoring program, tracking quolls on foot and by planes through rugged terrain. WILDLIFE ROUNDUP Farewell to the mallee emu-wren Wildfires in two South Australian conservation parks in 2014 have resulted in the loss of the last 60 breeding pairs of the Mallee emu-wren (Stipiturus mallee). The species is now extinct in SA. This tragic event has two harsh reminders for conservation managers: • A single population of an endangered species is not enough to provide certainty for the future. One or more insurance populations are the minimum strategy to support survival of small populations. Reduction of population size, and reduction of available territory has resulted in an increased risk of extinction for as many as 50 Australian mammal and 50 Australian bird species. • Inappropriate fire regimes threaten the existence of many endangered species across the country. Fire has always been part of the Australian environment, but it is the changing pattern of fire, such as the increase or decrease in its frequency, patchiness and intensity that is having the greatest impact on some of our most threatened wildlife. In 2009 the Black Saturday bushfires almost wiped out an entire population of Leadbeater’s possum in Victoria and burnt EDITOR’S NOTE: At last! Recognition of the role of digging and burrowing Australian animals in providing natural fire breaks and reducing fuel loads has begun to appear. Fires where wildlife is present are ‘cooler’ than the wild fires now so prevalent in our bushlands. The loss of wildlife such as bilbies, bandicoots, bettongs, numbats and even the lyrebird and malleefowl means a build-up of leaf litter on the soil, and the absence of browsers such as Photo courtesy Daryl Dickson. Photo courtesy Marcus Pickett. through 43 per cent of the species’ protected habitat, taking out many important nesting trees. The situation was made more critical by years of logging that reduced the number of suitable trees. With the assistance of the Friends of Leadbeater’s Possum and FAME, replacement nest boxes supported the remaining possums while their environment slowly recovered. Historically, fire was used by indigenous Australians to manage the bush. Patch or mosaic burning meant only small areas were burnt at one time, leaving safe areas for wildlife and ensuring a cool burn. The decline of traditional burning has coincided with the collapse of vegetation structures and mammal populations in many areas. Fires nowadays are so hot that they destroy all life, down to and including the ants that once were the first species to become active after a fire. With no place to shelter, animals that once waited out a fire before coming back to their territory are now either killed outright or become vulnerable to feral predators due to a loss of ground cover and shelter sites. It is clear that Australia needs some sensible strategies to manage the bush in the absence of wildlife and traditional indigenous fire regimes. small to medium wallabies means more undergrowth. These conditions, along with a greater frequency of severe weather events, promote hotter and more frequent fires. Research is now validating observations, usually at large-scale sanctuaries where such wildlife is present, that the reintroduction of digging and burrowing animals in some areas could play a role in fire management and possibly increase fire safety in the future. Anyone for bandicoots in the backyard? The endangered mahogany gliders of far north Queensland need connecting up. As one of Australia’s most threatened mammals and Queensland’s only listed endangered glider species, with a heavily restricted and drastically habitat where access to vital resources is disrupted every day (and every night), the mahogany glider is very familiar with disconnectivity. Sadly, 50% of the glider’s habitat has been cleared for agriculture, roads and residential development. On top of that, it is here that cyclone Yasi made landfall in 2011, impacting the entire range of the mahogany glider and devastating much of its already limited habitat. Page 4 Heroic efforts to provide emergency shelter sites and otherwise help the Mahogany Glider recover from the impact of cyclone Yasi were supported by FAME and were very effective, but destruction and fragmentation of habitat disrupts access to vital resources and places WILDLIFE ROUNDUP Bramble Cay Melomys gone forever The Bramble Cay Melomys, a small rodent that was only ever found on one small sand cay (island) in the Torres Straight off the tip of northern Australia, is the latest Australian mammal to go extinct. As we know, government funding of wildlife projects is dwindling despite the best efforts of wildlife departments around the country. Some are managing better than others, and some, such as the South Australian Department of Environment Water and Natural Resources, are working in partnership with organisations like FAME to obtain funds for species preservation. © The State of Queensland (Department of Environment and Heritage Protection). Discovered in 1845 and not seen since 2007, the Bramble Cay Melomys has been living life on the brink for many years. With a total of around 100 animals and a tiny territory (5ha - of which they occupied less than half) subject to erosion by wind and water, its very existence was a small miracle. Sadly, following a recent survey which failed to find even one of these lovely little animals, the Bramble Cay Melomys now seems to have gone forever. This latest extinction is of great concern to FAME, even though it is highly unlikely that we could have prevented it. There were no introduced predators, no loss of critical vegetation and no other visible reason. Short of a very expensive study, we will probably never know what caused the disappearance of the Bramble Cay Melomys. Since European colonisation 30 mammals (more than 10% of Australia’s mammal species) have shared this fate. Today the task of preventing any of the more than 1,850 animals and plants listed as threatened under Commonwealth legislation is overwhelming, and well beyond the resources of any one organisation. Although recovery plans for more than 800 species are in place, the vast majority are sitting on the shelf. the glider’s gene pool under threat. Wildlife Queensland’s Cassowary Coast Hinchinbrook Branch recovery team works tirelessly to identify key corridors of habitat and to reconnect, repair and restore them. Research conducted by leading Australian universities and wildlife services confirms fauna crossings to be an effective method of reconnecting target species with resources such as food, shelter and mates, significantly improving their reproductive and survival rates. Gliding poles, canopy bridges and vegetated medians enable target species to migrate across landscape barriers (roads, Page 5 HOW TO CHOOSE WHICH SPECIES TO SAVE? The recent appointment of a Threatened Species Commissioner by the federal government signals recognition of an urgent situation for Australian wildlife but we are all – government, non-profit, philanthropic organisations and donors – favouring some species over others every time we choose a project to support. Commissioner Gregory Andrews, who has been a veritable whirlwind since his appointment, recognises that his role is one of strategy, influence and facilitation rather than the allocation of funding. Australia desperately needs a national framework for action to guide decision making about the future of threatened Australian species. Commissioner Andrews is ideally placed to facilitate the development of such a framework. Ideally, this will include how to make decisions in the best interests of Australia’s vast landscape. Given that there simply isn’t the money to save everything, perhaps we should favour those species that help keep our soil, air, water and vegetation functioning to support life? Lovely as it was, the Bramble Cay Melomys did not (to our knowledge) rate highly against this criteria. power, rail), reducing the impact of the human-wildlife conflict and the threat of extinction. In the next step toward saving the endangered mahogany glider, the Wildlife Queensland team is now installing a 25m pole crossing and specialised camera monitoring system between two key remnants of mahogany glider habitat. They are also continuing a program of revegetation in the area by planting melaleuca and eucalypt saplings and juvenile grasstrees in key mahogany glider corridor and habitat sites. For more information about Wildlife Queensland’s Mahogany Glider recovery program visit: www.wildlife.org.au/v3/news/2011/mahoganyglider.html WESTERN QUOLL RESTORATION A GOOD INVESTMENT IN SCARCE RESOURCES Triage is a process used to determine where to place effort and resources when forced to choose between multiple casualties. Triage dictates that in extreme situations the best strategy is to help the victim with some hope of survival. In ecological terms, saving a key-stone species (one that has a positive influence on an entire ecosystem) has more value than saving one living in isolation. The project to restore the Western Quoll to arid Australia is a good example. Not only are we restoring a single species and strengthening its chances of survival, we are also restoring a key-stone species that will have a beneficial effect on an entire ecosystem. HOW DOES FAME CHOOSE WHICH PROJECTS TO SUPPORT? When it comes to choosing which project and which species to support, FAME uses some simple criteria: • any project FAME supports must benefit at least one endangered Australian species • project outcomes must increase the likelihood of long-term survival for the species involved. • species must be supported where possible in their natural habitat or as part of a project that will lead to their restoration to natural habitat • Vulnerable species must be protected from the influence of feral predators and competitors to the extent that the likelihood of survival is increased • Where research is the principle activity, that research must have the outcome of providing information to increase the chances of survival of one or more endangered species Photo courtesy Daryl Dickson. The number one threat to the survival of the Mahogany Glider remains habitat loss and lack of connectivity. FERAL FEATURE Latest toad control strategy – fence off that dam! It’s not realistic to think that they can be kept away from all Australian waterways, but University of NSW researchers now think that keeping cane toads away from outback dams may help in the long-term control of the pest in arid Australia It’s important to remember that while the toads have taken to semi-tropical and tropical areas where rainfall is high, most of their journey overland is through areas where water is scarce. These areas are also used by pastoralists for sheep and cattle and dams are a critical water source for livestock. UNSW scientists used tracking devices to analyse the movements and habits of the cane toad in its so-far unstoppable invasion of the continent and discovered that cane toads use these dams as refuges to survive Australia’s long hot dry seasons, moving on when rain falls. Observation showed that any single one of these dams might support a thousand toads. By building shade cloth fences around three dams on the edge of the Tanami Desert, scientists showed that after three days of trying to get through the fence during the dry season, cane toads died in large numbers. The fences were left in place through a full wet season and at the commencement of the next dry period toad numbers were ten to 100 times lower than around dams that were not fenced. The downside of this strategy is the cost and effort of maintenance of fences. Fences are not the only answer to the problem, but can help to control toads on a local scale and keep them at low numbers in areas where there is no other source of fresh water. Exclusion fences will now be one of a range of strategies being slowly developed by both scientists – and the community -in the ongoing battle to slow or halt the progress of Photo courtesy Brian Gratwicke the cane toad across Australia. There are still wild places in Australia, including massive lake systems in central Australia, which are really important for biodiversity conservation and could be destroyed by an invasion of toads. It will be critical to find the best combination of strategies before these precious places are reached and taken over by these poisonous pests. Visit http://www.canetoadsinoz.com/ to read about the work being done at the University of Sydney by Prof Rick Shine and colleagues (supported by FAME) to stop the toad. Rock wallaby rebounds in WA wheatbelt An increase in the numbers of a critically endangered Black-flanked Rock Wallaby population in WA is the result of predator-proof fencing to exclude the foxes and cats that reduced the population to less than five, including just one female. Nangeen Hill Nature Reserve, near Kellerberrin, was home to this tiny group. The area has been baited continually for many years to control feral predators, but the wallaby population continued to decline and wildlife workers believed they would disappear completely without help. For some animals, the presence of a predator produces a reaction that is so strong it overcomes even the instinct for food. The Nangeen wallabies were too frightened to go beyond the safety of their rock shelters to graze, and were clearly suffering from starvation and a failure to thrive. To protect the population and give it a chance to survive, a five-kilometre long electric fence was built in 2013 around the Black-flanked Rock Wallabies in their nature reserve, and 22 wallabies (some from other remnant populations) were introduced into this protected area. Since then, according to Department of Parks and Wildlife flora and fauna conservation officer Natasha Moore, the wallaby population has jumped to 39. The plan is to allow the wallaby colony to grow within the reserve and use some of the animals to repopulate other Page 6 struggling colonies elsewhere in the state. For most wildlife projects fencing is not a long term solution although feral free natural habitat, protected by a predator-proof fence, is without doubt the most effective strategy Photo courtesy Mt Rothwell. for vulnerable wildlife. Unfortunately it is also the most expensive and for this reason is not likely to be used without significant public or philanthropic support. Even then long term costs are daunting. Most of Australia’s threatened mammals are at risk because of foxes and cats. Fenced areas are an important tool for wildlife protection. At this time so is shooting, baiting and trapping of feral predators and competitors. The ‘holy grail’ of wildlife protection is permanent removal of feral predators from the bush – not likely in the short term. There are, however, wildlife experts dedicated to finding that grail. One such is Dr John Read, whose feral cat ‘grooming trap’ continues to show great promise and will be trialled on Kangaroo Island this year (see the article about Kangaroo Island’s cat control program in this newsletter). If successful, this trap could replace other less humane and more labour-intensive methods of cat control. The trap is not intended to be a money-maker. In fact, the intent is to produce a device that can be mass-produced at a modest cost and made available to all comers. We expect demand to be enormous. FERAL FEATURE Photo courtesy Andrew Cook, Invasive Animals CRC. Kangaroo Island leads the way with its Feral Cat Reduction Program. The 4400 square kilometres of SA’s Kangaroo Island are some of the most fortunate in Australia as they are free of the introduced pests the fox and the rabbit. The effect this has on the Island is some amazing wildlife abundance and diversity. Unfortunately the island is not free of feral cats. The Island’s feral cat population is estimated at around 5000 and more than 90% of Island residents are in favour of controlling un-owned cats. (Surveys, 1993 & 2005) Since the early 2000’s the Island has had a Cat Control Committee which served to raise awareness of the impact the Island’s feral cat population had on biodiversity and on the fat lamb industry through transmission of the disease Sarcocystis. Sarcocystis is a disease that infects the meat of the sheep and, if present, downgrades the value of the meat. The presence of Sarcocystis may have a serious effect on annual farm income. More recently, in 2010 the Kangaroo Island Council introduced By-laws that called for annual registration, micro-chipping and desexing of all domestic cats. In addition, the by-law limits the number of cats to one in a small dwelling, and two in any other dwelling. The owner of the cat must effectively confine Page 7 the cat to their own property. The current KI Council is putting together a strategy for the reduction of feral cat numbers and further management of domestic cats. The long term aim of this strategy is to achieve a cat free island. These strategies will require the participation and cooperation of the Island’s ratepayers, the Natural Resource Management (NRM) Board and the Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources (DEWNR). In February this year Threatened Species Commissioner Gregory Andrews visited the Island and encouraged the KI NRM and the KI Council to move beyond policies and the begin work on the project. (The Islander, 12/2/2015). FAME has recently resolved to support the development and trial of an innovative cat trap that recognises the target is a cat and delivers a poison in spray form that the cat ingests while grooming. The developer of the Grooming Trap is hopeful that a trial of traps on Kangaroo Island will begin in the near future. If successful, the new traps will be used in conjunction with other methods to seriously reduce the Island’s feral cat population over the next few years. Both wildlife and the Island’s important sheep industry will benefit. EDITOR’S NOTE: FAME congratulates the KI Council for taking this step. Cats are widely recognised as a massive problem for Australian wildlife, but not many realise the dangers that cats pose to the pastoral industry. FAME has been working away at this issue for some time, including funding a research project into the effect of feline toxoplasmosis (a disease spread through cat droppings) on wildlife – quolls and bandicoots in particular – and sheep. It was discovered that the presence of toxoplasmosis can cause ewes to abort lambs, and that toxoplasmosis was implicated in the decline of (among other native wildlife species) the now critically endangered Eastern Barred Bandicoot and the Eastern Quoll. FERAL FEATURE Canberra Indian Myna Action Group gains national recognition Congratulations to the Canberra Indian Myna Action Group (CIMAG) and to President and Founder Bill Handke, who is also a long-time FAME member. In 2013 the Keep Australia Beautiful National Environmental Innovation and Protection Award recognised CIMAG’s efforts to protect the local environment from the threats posed by Indian Mynas. This recognition was supplemented with an Award by the Conservation Council of the ACT Region to CIMAG President, Bill Handke, in 2014 – the “2014 ACT Environment Award” - for protecting the environment as Founder, President and driving force of the CIMAG myna control program. CIMAG has done the impossible: making sightings of native birds more common in Canberra backyards than those of the invasive Indian Myna. Myna numbers in the Canberra region continue to decline. They are now the 18th most common bird – compared to the 20th most common bird in the previous survey year. CIMAG now has an impressive list of achievements, including 50,550 known removals of Indian Mynas since the group was established in 2006! In addition there are now at least 43 Indian Myna Action Groups operating in eastern Australia, including Victoria, Queensland and NSW. Sadly, where Indian Mynas are being reduced in some areas, the Myna invasion is expanding on other fronts. News that the Indian Myna is spreading westward have been confirmed by sightings in Parkes and other outback NSW centres. Although the Indian Myna is a resilient bird, it is a pest whose attributes make it highly suited for wide-scale community trapping: it is sedentary; commensal – ie lives around people; conspicuous – always around; social - so it flocks; unpopular; and readily enters traps for food. The community-action approach is highly desirable as it enables high numbers of traps to be deployed by the community at little or no cost to government, and with the prospect of significant captures and thus impact on myna numbers.* *Information drawn from “Myna Matters”, the newsletter of the Canberra Indian Myna Action Group. From the editor’s desk Australian predators – mammals that prey on other species - have been demonised since colonisation. Our largest natural predator, the Tasmanian Tiger, was driven to extinction in 1936. Others, such as the Tasmanian Devil and four species of quoll, have been reduced in number and range. All are at risk of extinction. Despite a growing body of evidence that dingos suppress cat and fox density and enable the survival of vulnerable wildlife, and even demonstrations that semi-arid cattle ventures are more profitable when a healthy dingo population is present (because they keep kangaroo numbers down), it is unlikely that the dingo will be accepted for widespread re-introduction anytime soon. Attention is now on remaining, less hated natural predators such as devils and quolls. International research shows that top predators are an essential part of healthy ecosystems. Dingos, devils and quolls are keystone species – according to Wikipedia ‘a keystone species is a species that has a disproportionately large effect on its environment relative to its abundance.’ Such species play a critical role in maintaining the structure of an ecological community, affecting many other organisms and helping to determine the types and numbers of various other species in the community. Think of a keystone species as being similar to a keystone in an arch. While the keystone is under the least pressure of any of the stones in an arch, the arch still collapses without it. In nature, an ecosystem may experience a dramatic shift if a keystone species is removed, even though that species was a small part of the ecosystem. Before humans began to dominate and change the natural world keystone predators maintained a healthy balance between species. But remove the top predator and grazing animals can breed out of control until their behaviour becomes destructive: remove wolves (in the US) and elk over-graze willows until stream banks erode; remove the dingo in Australia and kangaroos breed up until they become a serious problem for pastoralists. Reduction of Tasmanian Devil numbers by up to 90% is ringing alarm bells for conservationists. Just as rabbit numbers on the mainland only exploded after quolls began to disappear, there are fears that feral animals will boom on the island without the devil to keep them under control. If this happens, a range of unique species that now survive only on Tasmania could disappear completely. On the Australian mainland the fox and the cat have taken over where the dingo once dominated. However, in those few wild places where dingos still exist foxes and cats take a back seat and wildlife benefits. ‘Re-wilding’ is the latest buzz word in conservation circles. This means bringing back natural conditions to the Australian bush, starting with natural predators. Top of the list is the Tasmanian Devil, but thanks to FAME’s early success in restoring the Western Quoll to its original territory widespread reintroduction of the quoll - a much less threatening candidate - is also on the horizon. Our project is being watched closely and – if it goes the distance and results in the reestablishment of the Western Quoll in the Flinders Ranges – will provide a template for other such projects in the future. Go the quoll! Cheryl Hill, Editor and CEO FAME NEWSLETTER is published by the Foundation for Australia’s Most Endangered Species Ltd ABN 79 154 823 579 PO Box 482 MITCHAM South Australia 5062 Tel: 08 8374 1744 Email: [email protected] Web: www.fame.org.au Articles in this publication can be reproduced with acknowledgement. Your support can help FAME restore the balance to arid Australia, beginning in the Flinders Ranges of South Australia. Visit www.fame.org.au Page 8 Produced by sarahbennettdesign.com.au I’m pleased to report that the concept of returning top predators to the Australian bush is gaining momentum.

© Copyright 2026