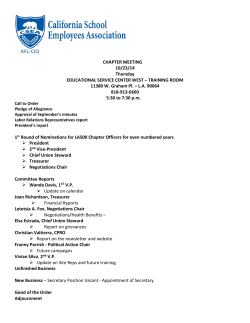

The Bipartisan Congressional Trade Priorities and Accountability Act