Online Synonym Materials and Concordancing for EFL College Writing

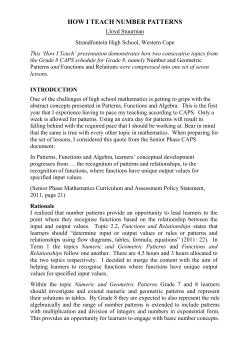

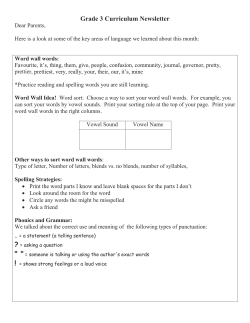

Computer Assisted Language Learning Vol. 20, No. 2, April 2007, pp. 131 – 152 Online Synonym Materials and Concordancing for EFL College Writing Yuli Yeh, Hsien-Chin Liou* and Yi-Hsin Li National Tsing Hua University, Taiwan The phenomenon of overused adjectives by non-native speaking learners (NNS) has been pinpointed by recent research. This study designed five online units for increasing students’ awareness of underused specific adjectives for EFL college writing. Five units were developed for five identified overused adjectives: important, beautiful, hard, deep, and big. In each unit, data-driven learning materials, incorporating a bilingual collocation concordancer TANGO, first had learners engaged in distinguishing synonymous adjectives from concordance lines as their first task. Then three exercises for practise followed as a second task. Nineteen English majors in a college freshman writing class participated in the study. The assessment measures included three tests, two in-class writing tasks, and questionnaires. The findings indicate that, in addition to improvement in the immediate posttest, students’ word knowledge for synonym use was still retained as measured two months later in the delayed posttest. Moreover, in the post-instruction writing task, students avoided using general adjectives, tried to apply more specific items, and thus improved their overall writing quality. As for students’ attitude toward the learning units, over half reported that inductive learning was beneficial although they still found it difficult to verbalize differences among semantically similar words. TANGO was also considered a useful tool for learning synonyms and their collocates. For effective and successful communication in writing, second language learners are instructed to use specific words and to avoid using general terms or overused modifiers. A case study by Granger and Tribble (1998) comparing the corpora of French learners of English as a foreign language (EFL) and of native speakers (NS) explicitly pointed out the prominent phenomenon of overused adjectives by nonnative learners (NNS). The EFL learners were found to be very dependent on superordinates such as real, important, and different throughout their text, an *Corresponding author. ROC Department of Foreign Languages and Literature, National Tsing Hua University, Taiwan. Email: [email protected] ISSN 0958-8221 (print)/ISSN 1744-3210 (online)/07/020131–22 Ó 2007 Taylor & Francis DOI: 10.1080/09588220701331451 132 Y. Yeh et al. indication of lexical poverty in most of the learner output. The adjectives learners overuse is what Ham and Rundell (1994, p. 178) address as default terms, a factor which makes a writing task ineffective. The finding provides pedagogical implications for EFL teaching and learning—that learners should be encouraged to employ words with a higher degree of specificity for successful communication. To solve the above-mentioned problem, the use of concordancing for data-driven learning (DDL) could be an alternative to help learners. DDL presents abundant examples to expose learners to authentic language and to let them discover rules from contextual clues in corpus evidence (Johns & King, 1991). Furthermore, presenting concordance data to learners can help learners successfully discriminate among semantically similar items and attend to the collocation patterns and semantic features (Partington, 1998). The purpose of the present study, therefore, is to develop and evaluate online DDL learning units for helping learners apply more specific synonymous alternatives, instead of overused adjectives, for better writing. Vocabulary and Writing The importance of word selection for writing has been recognized by scholars such as Johnson (2000), who stresses that a writer has to use precise diction to express the intended messages. Studies have shown that vocabulary improvement and lexical selection in writing tasks are also emphasized by evaluators of student writing (e.g. Engber, 1995; Santos, 1988). To illustrate, Engber (1995) found that the diversity of lexical choices and the correctness of lexical forms had a significant effect on reader judgment of the overall quality of essays written by L2 writers of intermediate to highintermediate proficiency. Likewise, Santos (1988) reported a study investigating the reaction of 178 professors to two compositions written by a Chinese student and a Korean student. One of the major findings of research is that lexical errors are considered the most serious problem in learner output. Taking into consideration the frustration that learners experience when they spend so much time searching for appropriate lexical items but still have difficulty expressing themselves precisely, Santos (1988) suggested that lessons on vocabulary building and lexical selection be incorporated into ESL writing courses. These vocabulary lessons should be designed with emphasis on the importance of lexical choice and elicitation or presentation of synonymous expressions. Researchers also advocate applying the results of corpus analyses to pedagogy. Flowerdew (2001) has suggested that the findings from these comparative studies of native and non-native corpora be utilized in designing materials to address students’ needs and deficiencies, as in the case of the compilation of dictionaries for NNS. Instead of giving form-focused instruction based on language teachers’ intuition, Granger and Tribble (1998) propose the utilization of NNS learner data for a more systematic account of learner difficulties. Tschichold (2003) has also explicitly recommended that computer assisted language learning (CALL) activities be adapted to help learners actively practice alternative words or expressions for Synonym Units and Concordance for Writing 133 overused items. Such vocabulary enhancement activities would better serve to strengthen learners’ knowledge of the target adjectives when the presentation of the teaching materials is based on analyses of actual learner corpora, instead of on teacher intuition. Learner Corpus Evidence about Word Use Problems The corpora stored in a computer allow researchers, teachers and students to exploit a huge amount of authentic data in their study of language, instead of simply depending on their intuitions (e.g. Chambers, 2005; Horst, Cobb, & Nicolae, 2005). Among various types of corpora, learner corpus research may provide more insights into learners’ weaknesses. Quite a few studies have been carried out to probe into the differences between learner corpora and native English-speaker corpora so as to offer insights to EFL teachers. For instance, Ringbom (1998) found that the verb ‘‘think’’ occurred more frequently in the non-native learner corpora than in the nativespeaker corpora. Learners were also found to use certain other vocabulary items of high generality, such as people and things, with a higher frequency than native speakers did. The use of adjectives, in particular, was investigated by Granger and Tribble (1998) through a comparison between the Louvain corpus (227,964 words, writing by French learners of English) and a core subset of the British National Corpus (1,080,072 words). The study showed that advanced French learners of English used such adjectives as real, different, important, longer and true more frequently than proficient NS writers. It revealed that learners tended to be over-reliant on superordinate adjectives such as important in their academic writing, while excluding words with higher degrees of specificity, such as critical/crucial/major/serious/significant/ vital. Another contrastive study specifically focusing on Chinese learners of English was conducted by Gui and Yang (2002). They developed a Chinese Learner English Corpus (CLEC), which comprised 1,185,977 words from compositions of intermediate to advanced learners, and compared CLEC with other corpora of English speakers. The comparison of big, great, and large used in CLEC and the Freiburg Lancaster – Oslo/Bergen Corpus (the Freiburg update of the Lancaster – Oslo/Bergen Corpusand with one million words of edited written British English) revealed that Chinese learners used great more frequently. Gui and Yang (2002) point out that Chinese learners regarded great as a general intensifier applicable to any situation. Moreover, the misuse of big and large indicated that learners were still not familiar with their collocates. Corpus-based Approaches for Vocabulary Learning Traditional approaches to using a print dictionary, glosses, or lists of synonyms may not provide adequate help to L2 learners. The study by Harvey and Yuill (1997) gives a detailed account of the role Collins COBUILD English Language Dictionary (CCELD) (1987) played in the completion of written tasks by EFL learners. 134 Y. Yeh et al. The learners were required to identify and distinguish various types of information about a word they could look up in the dictionary. Of the look-ups, synonym searching was among the most frequent activities. However, 36.1% of synonym searches were reported to be unsuccessful. In almost all these unsuccessful cases, the users indicated that the dictionary entry did not give them the information they needed in order to use the synonyms. Although CCELD offers an extra column for main source synonyms, it fails to present explicitly with the synonyms their register, connotation, difference of nuance, or collocations, and contextual clues that will make learners confidently choose an appropriate synonym for use from the list. Harvey and Yuill conclude that providing synonyms in conjunction with their collocational patterns and semantic features, and providing stylistic guidance rather than implied equivalence alone, is essential. Corpus data with such information, therefore, is a powerful alternative for vocabulary learning and teaching. Martin (1984) examined vocabulary errors in university-level expository writing and concluded that the teaching of vocabulary via glosses or lists of synonyms in the target language could possibly lead to improper lexical choices, as learners might take two synonyms as exactly interchangeable alternatives and ignore their subtle differences. Therefore, learners should be guided to notice whether synonyms behave identically in all contexts and to recognize the fine distinctions among semantically related words. Teaching materials should offer learners chances to compare and contrast new words so as to identify the nearest collocates and the different situations in which each one occurs. Concordance-derived materials provide such classroom opportunities to overcome students’ difficulties in vocabulary use. A concordance shows the context of a keyword or key phrase for user query, a process called concordancing. Hunston (2002) modified a concordance-based activity to focus on the problem of the underuse and overuse of vocabulary items in the target language. Learners were first provided with concordance lines from a native-speaker corpus presenting adjectives with higher specificity, such as serious, major or critical. Then, the general word, in this case important, was removed and learners were asked to replace it with one of the suggested alternatives. The vocabulary enhancement exercises aimed to help learners increase their awareness of the words they tended to underuse. Other studies have examined the effects of concordancing (learning through computer key word search programs within a corpus) on various aspects of language learning (e.g. Chambers, 2005; Chan & Liou, 2005; Horst et al., 2005). For instance, Horst et al. combined the use of a concordance, a dictionary, a cloze-builder, a hypertext, and a database with interactive self-quizzing features in several ESL courses for academic English and evaluated the effects of those tools and activities on 150 students. Statistic analyses evidenced the learning gains from the tools, and the contextual sentences provided support for vocabulary learning. To pinpoint how corpus consultation can assist language learning, Chambers (2005) examined the process of students’ consultation of corpora, including choice of search word(s), analytical skills, problems encountered, and their evaluation of the activity. Although she found that corpora consultation could complement foreign language learning in Synonym Units and Concordance for Writing 135 various educational contexts, limitations such as the small size of corpora and the lack of learner training were also found. Two studies specifically focusing on Taiwan EFL learners were undertaken by Lee and Liou (2003), Yeh (2003), Sun and Wang (2003), and Chan and Liou (2005), who investigated the feasibility of incorporating a web-based monolingual English concordancer as an electronic referencing tool into traditional senior high or college English classes for vocabulary learning. Forty-six second-year senior high school students in an intact class were involved in the study of Lee and Liou (2003) and were categorized into three groups of high, intermediate and low vocabulary levels. The findings first indicate that students with lower vocabulary proficiency seemed to catch up with students at the high vocabulary level after concordance learning. In other words, concordancing has the potential for scaffolding weak learners to accelerate their vocabulary acquisition. Moreover, students with inductive learning styles benefited most from the concordancing learning experiences. Students’ attitudes toward the use of concordancing was positive and they were willing to use the tool for vocabulary learning in the future. Similar findings were reported in Yeh’s (2003) study on 23 college learners focusing on the effects of self-selected concordances and individual learning styles. The results indicate that concordancing-based vocabulary learning does help with learners’ word use, particularly for learners who show an inclination toward inductive learning. Further, Sun and Wang (2003) and Chan and Liou (2005) explored the effects of online interactive collocation exercises, with concordancers incorporated, in EFL settings, since mastery of collocations (word combinations) has been claimed to be an important aspect of learners’ vocabulary competence (e.g. Wray, 2002). Sun and Wang (2003) randomly divided 81 senior high students into two groups. The two groups used corresponding online exercise versions designed with either a deductive or an inductive approach. Posttest results indicated that the overall the inductive group showed significantly more improvement than the deductive group. Easier collocations were learned more effectively when the inductive approach was incorporated into concordancing. Chan and Liou (2005) investigated the use of five web-based practice units, with an online Chinese – English bilingual concordancer incorporated, for learning English verb – noun collocations. Thirtytwo college EFL students participated in the study. Results indicate that learners made significant improvement on collocations immediately after the online practice but regressed later. Yet, the final performance was still better than students’ entry performance. Different verb – noun collocation types resulted in different practice effects. Learners with different prior collocation knowledge were also found to perform differently as far as the practice effects were concerned. Both the online instructional units and the concordancer were acceptable to most participants. It seems that concordancing-based CALL exercises could be beneficial for English learning, particularly when aspects of vocabulary or collocations are included. Yet few previous studies have examined the impact of concordancing on the learning of synonymous adjectives, despite the fact that, according to learner 136 Y. Yeh et al. corpus analysis, some adjectives tend to be overused and thus weaken students writing. The Current Study Research on concordancing suggests that learning synonyms, through a learner’s active analysis of corpus data, may help learners clarify differences in meaning and thus enhance vocabulary competence. Furthermore, words with apparent similarity in L1 meaning should be taught with their typical collocates in context (Harvey & Yuill, 1997; Partington, 1998). Therefore, it may be beneficial to design concordance-based materials with the aim of increasing learners’ awareness of collocations of nearsynonyms for appropriate word use. Following principles for designing concordancebased exercises (Hunston, 2002), our study has analyzed NNS learner data in identifying learning difficulties and developed online materials focusing on five overused adjectives by EFL learners. The current study seeks to address four research questions: 1. Are the designed online learning units effective for students’ learning of synonymous adjectives in a controlled test? 2. Can the online materials improve students’ use of synonymous adjectives in writing? 3. How do students perform in inducing patterns or finding out the differences among synonymous words when they use a bilingual concordancer? 4. What is students’ feedback on the online materials? A one-group pretest – posttest design was adopted to address the issue under investigation. An intact class of 19 college freshman English majors from a public university in Taiwan participated in the study. The participants took freshman writing as a required course, having two 50-minute class periods per week. Most of the students had received formal instruction about English for six years during their junior and senior high school years. Due to the more authoritative roles of teachers in Chinese culture and the time constraints placed upon the students because of the college entrance exam, most participants were more accustomed to deductive learning in which teachers presented rules in order to save time. Most learners would be challenged in an environment which required the cognitive skill of induction. Two types of instruments, tests and questionnaires, were used in the study to collect data for the research questions. A test with 15 translation and 15 gap-filling items, equally distributed to five sets of synonyms—important, beautiful, hard, deep, and big was designed. The 30 items in the pretest, posttest, and delayed posttest were identical but sequenced differently in each of the tests. A background questionnaire (with 25 items) was designed to obtain information about students’ background and their preference for learning at the outset of the study. An evaluation questionnaire of 21 items examined students’ perception of the online practice after the experiment period. Synonym Units and Concordance for Writing 137 Development of the Online Synonym Materials for the Study Since insights derived from the analysis of learner corpora can provide a basis for reducing learners’ overuse of adjectives (Granger & Tribble, 1998), the present study initiated a comparison between a non-native speaker (NNS) corpus of EFL learners in Taiwan and a native speaker (NS) corpus before designing the online units. The NNS learner corpus contains, with a total of 114,045 words, descriptive and argumentative essays by freshman English-major students in a public university. The NS data for contrastive analysis is LOCNESS (Louvain corpus of Native English essays, part of the International Corpus of Learner English, http://www.fltr.ucl.ac.be/fltr/germ/etan/ cecl/cecl.html) corpus, consisting of 66,598 words of argumentative writing by British students. In analyzing the NNS corpus, a self-developed error-coding scheme was used to tag errors in the corpus, and word choice was found to be the most frequent type of error. Further analysis was then carried out by comparing word frequencies in the two corpora so as to identify overused adjectives by EFL students. The results yielded from the comparison showed that learners tended to use five relatively general words—important, beautiful, big, hard, and deep—with a frequency 20 times greater than native speakers did. These words were thus chosen as the main focus of the online synonym units to help reduce the phenomenon of overuse. Further steps were taken in selecting the synonymous adjectives to be included as the content of the units. First, we selected synonymous words for the five general adjectives from WordNet because it provided detailed information for distinguishing semantically similar words. WordNet (http://wordnet.princeton.edu/), an English lexical database, is an online reference system developed by a group of linguists, psycholinguists, and computer experts at Princeton University (Miller, Beckwith, Fellbaum, Gross, & Miller, 1993). Next, we selected from the list of words we identified from WordNet only those words with higher frequency in the British National Corpus (BNC, a balanced synchronic text corpus containing 100 million words with morphosyntactic annotation, http://www.natcorp.ox.ac.uk/) to serve as the target words for learning, since Tschichold (2003) stressed that learners needed to be offered comprehensible alternative words or expressions for practice. Finally, to facilitate successful learning with induction from concordance lines in TANGO, only synonyms with sufficient instances provided by the Sinorama parallel corpus (from which the concordancer, TANGO, was derived) were selected. Table 1 illustrates one Table 1. An example of a general word with its synonyms in the online unit Overused adjectives Alternative words (synonyms) Unit 1 important Crucial Influential Significant Serious Vital 138 Y. Yeh et al. example of one overused adjective important and its synonyms selected for the exercises. In total, 25 words, five synonyms for each of the five overused terms, formed the target word list to be covered in the online materials. An Online Collocation Aid, TANGO As mentioned above, encouraging learners to study collocational patterns of semantically similar words should be effective for the teaching of synonyms. Therefore, a collocation aid (Jian et al., 2004) was incorporated into the online materials. This online aid, named TANGO, is a summarized version of a Chinese – English bilingual concordancer with its output display focusing on specific collocates for the query word a user types in (Wu et al., 2003). As shown in Figure 1, TANGO is a web-based electronic referencing tool that can retrieve adjective – noun (AN), verb – noun (VN), verb – preposition – noun (VPN) collocations from the Sinorama Chinese-English parallel corpus, English Voice of America corpus, and British National Corpus (for TANGO, see http://candle.cs.nthu.edu.tw, under the NLP tools). Sinorama is a 40-million-word encyclopedic and bilingual electronic textual database about facts of Taiwan; it was originally a collection of articles from an official monthly magazine published in print over three decades, 1975 – 2002 (now available online at: http://www.sinorama.com.tw/en). When a user types in a word, TANGO can display relevant citations from the bilingual corpus Sinorama or the monolingual corpus of VOA or BNC. The information presented will include (a) clustered citations according to their collocates, (b) occurrence counts, Figure 1. TANGO with the display of AN collocates Synonym Units and Concordance for Writing 139 (c) highlighted words and collocates, and (d) sorted citations listed according to the frequency of the collocation. Therefore, when a user submits a query for the adjective ‘‘critical’’ from the Sinorama corpus, possible AN collocates are displayed as Figure 1 illustrates. One distinguishing advantage of the bilingual collocation aid from Sinorama is that the highlighted collocates are shown with translated equivalents in context. With Chinese counterparts available, users can view and examine easily relevant instances that they need. Therefore, the collocation concordancer could be beneficial to EFL learners by allowing them to induce rules or patterns by themselves. In the practice units designed for synonyms, there were in total five learning units, one for each of the five overused words identified, developed in the online environment CANDLE (http://candle.cs.nthu.edu.tw, use candle/candle to login, choose synonyms under WriteBetter of the ‘Writing’ component). Each unit contained an introduction page, a list of synonymous words with links to examples in TANGO, and two tasks for induction and practice. To begin the induction task, learners read the example sentences of each target synonym and made notes, on a notepad online, of patterns they induced from the sentences. A summary page of the patterns a student induced on how the synonyms can be appropriately used was then filled in (see Appendix B for an example of a student summary). After the induction task, three types of exercises were provided to reinforce the learning of synonymous adjectives: substitution, gap-filling and translation (see Appendix A for an illustration). In the substitution exercise, sentences with an overused adjective were presented for students to replace the adjectives with more specific words. Gap-filling exercises required learners to fill in acceptable alternative target words. Finally, learners’ input for sentence-level Chinese – English translation items was checked by the program to see if target adjective words appeared in the answers. The system provided feedback on whether learners used the right word and presented an acceptable corresponding English sentence for reinforcement. An online tracker program kept records of all student responses to the exercises in the practice task, in addition to the notes they took in the notepad and summary pages of patterns induced in the first induction task. The research procedures of the study included three stages. First, the background questionnaire and the pretest were administered to all the participants. In addition, they were asked to write with pen and paper an essay on the topic, ‘‘Why I chose to study at Tsing Hua University’’ in about 30 minutes in class. For orientation, they were also instructed on how to use the online learning units in a demonstration provided by the researcher. Next, in the four-week treatment stage, students were required to do the two tasks in class for 20 minutes and complete the rest after class each week. The five units were completed within four weeks, one unit in each of the first three weeks and two in the fourth week. Last, in the posttest stage, students took the immediate posttest and filled out the evaluation questionnaire. The researcher followed-up the evaluation questionnaire by interviewing students for general comments about the units or for further clarification of their responses to the evaluation questionnaire. Students took the delayed posttest eight weeks after the immediate posttest. They also wrote a second composition about describing to an 140 Y. Yeh et al. international student their college life at Tsing Hua University. In both of the composition writing assignments, students were writing in class without access to TANGO or other reference tools. Results and Discussion To answer the aforementioned research questions, the results of the tests, students’ use of adjectives in writing, their performance in induction, and their feedback on the online units are presented below with discussion. Learners’ Performance and Retention as Measured in Controlled Tests First, how learners performed in the three controlled tests was investigated. Due to the small sample size of the subjects (N ¼ 19), the statistic nonparametric method, the Wilcoxon Signed Rank Sum (Keller & Warrack, 2002), was employed to analyze the test results. Comparisons were made to see if there were significant differences between (1) total scores of the pretest and the posttest (see Table 2) and (2) total scores of the posttest and the delayed posttest. The total scores of the posttest (each item worth 3 points, 90 in total for each test) was significantly higher than the pretest (p ¼ 0.000 5 0.05), and no significant difference was found in the comparison of the posttest and the delayed posttest (z ¼ 72.14, p 4 0.05). Hence, the positive results indicate that students’ knowledge of synonyms had increased significantly in the controlled tests. Additionally, students generally did not show much regression in the delayed posttest, as indicated by the comparison with those of the posttest scores. The answer to research question one, therefore, is that the online units did enhance students’ learning of synonymous words and the effects can last over a period of eight weeks, when learners were measured by test items. Since the test was composed of questions equally distributed to the five sets of adjectives, further analysis was conducted to examine how well students performed with regard to each set of adjectives and which synonymous adjectives were more effectively learned by the participants with the online design. Figure 2 shows the mean scores for the five sets of synonyms at the time points of the pretest, the immediate Table 2. Comparison of test scores between the pretest and the immediate posttest N Immediate Post – Pre Negative ranks Positive ranks Ties Total 0a 19b 0c 19 Mean rank Sum of ranks 0.00 10.00 0.00 190.00 Z score Asymp. sig. (one-tailed) 70.318a 0.000* *p 5 0.05 a. Immediate post5pre; b. immediate post4pre; c. immediate post ¼ pre. Synonym Units and Concordance for Writing 141 Figure 2. Changes in the mean scores for the five sets of synonyms across three time points posttest, and the delayed posttest. The results reveal that the mean score of hard was the lowest in the pretest. In the immediate posttest, important had the highest mean while the mean score of hard was still the lowest. Yet students obtained the lowest scores for big in the delayed posttest. Thus, it is inferred that students were able to learn more about the synonyms of important but not as much for the synonyms of hard after the online learning. Compared to synonyms for the other four adjectives, the learning unit for the synonyms of big seems to have been less effective for students. The change in patterns of the mean scores for the five word groups warrants further research as the difference may be attributed to either item difficulty or the association strength of the adjective – noun collocations presented. The findings of improvement shown by the controlled tests echo results in studies by Lee and Liou (2003) as well as Yeh (2003), indicating that positive effects of concordancing on vocabulary learning were found. Similar to the studies of Sun and Wang (2003) and Chan and Liou (2005) in which online concordancing practice had been proven to be effective in the learning of collocations, the results of the present study also indicate that learners’ knowledge of adjective – noun collocation is enhanced as demonstrated by higher test scores. Learners’ Changes of Word Use in Writing In addition to improvement illustrated by test scores, we also investigated whether the online materials designed would have an impact on learners’ writing. To analyze the two student essays completed before and after the online learning, the ESL Composition Profile (Jacobs et al., 1981) with analytic scales for the five components in an essay (content, organization, vocabulary, language use, and mechanic with a total score of 100) was adopted for rating the overall quality. Two raters (graduate students in an MA-TEFL program) were involved in grading the essays and the 142 Y. Yeh et al. scores were averaged with high inter-rater reliability (r ¼ 0.96). It was found that, except for the two scores for language use and mechanics, scores for all the other components, including that for the vocabulary category, and the total scores showed significant differences between performance on the pretest and posttest essays (all p’s in the designated categories were smaller than 0.05, see Table 3). This may suggest that, combined with the teaching in the writing class, the online materials made an impact on both overall writing quality and individual aspects of content, organization, and vocabulary of essays written. The vocabulary aspect of ESL Composition Profile covered the range of words, word/idiom choice and usage, and word form mastery in writing. As this study focused on adjectives, a further step was taken to examine more closely how students actually used the target adjectives in writing. We first calculated both the total number of words and the observed adjectives (the five overused adjectives, important, beautiful, hard, deep, and big, and their specific synonyms, 30 target words) in the two batches of essays, respectively. The first batch had a total of 3336 words with 17 general adjectives, while the second batch had 4578 words in total with 30 general and 21 specific adjectives. Our next step was to normalize the length of essays, that is, total words were divided by 100 to obtain the unit number for each composition. Since not all students used the observed adjectives in both essays, we could only include 10 students, out of the total 19, who employed the target items in both their first and the second essays for our discussion. It seemed that some learners chose to avoid using particular words or structures in their free writing. Another reason might be that the topic constrained students’ use of certain words, for instance, the nonoccurrence of the adjectives of hard and deep. Table 4 shows the general and specific adjectives used by the 10 students. There were four trends of students’ word use of specific or general adjectives in the two batches of essays written at different time points. In the first trend ‘‘no change’’, students S1 and S14 still used only general and overused items with no seeming awareness of employing specific alternatives in their essays, after learning from the online materials. They might either need more time to learn or the online materials were not effective for these students. In the second trend, students S9, S16 and S18 did not improve in using general words but had tried to apply specific adjectives in their writing. With more use of adjectives, more mistakes were found in the posttest essays. We may call this a ‘‘restructuring’’ group whose interlanguage lexicon might Table 3. Comparisons of the pretest and posttest essays regarding total scores and component scores Z Asymp. Sig. (one-tailed) *p 5 0.05 Total Content Organization Vocabulary Language use Mechanics 73.826 0.000* 73.836 0.000* 73.269 0.000* 71.832 0.034* 71.350 0.089 71.292 0.098 Synonym Units and Concordance for Writing 143 Table 4. Students’ adjective use in their pretest and posttest essays Essays written in the pretest stage Trend General/Unit Specific/Unit Essays written in the posttest stage General/Unit 1 S1 S14 1/1.44* 1/1.6 3/2.61 3/2.21 2 S9 S16 S18 1/1.66 3/1.68 1/1.99 2/2.06 6/2.13 1/1.57 3 S6 S8 2/1.83 1/1.09 1/1.37 2/2.38 4 S12 S15 S17 1/2.03 1/1.55 2/1.49 1/2.66 1/2.53 Specific/Unit 1/2.06 3/2.13 1/1.57 1/2.66 2/2.53 1/2.59 Note*: 1/1.44 means the Subject used one general adjective in his/her 144-word essays in the pretest stage. have been pushed up but have not yet reached the native-speaker’s norm (Bialystok & Sharwood-Smith, 1985). During the restructuring process, more mistakes surface in order to re-package what is learned into linguistic structures of a higher level. S6 and S8, in the third category, had reduced the number of overused items, given the consideration of word use frequencies and changes in essay length. They avoided the use of general words in writing, but chose not to take risks in using specific words which they might not have acquired yet. Finally, there were students who not only avoided general adjectives but also learned to use words with a higher degree of specificity, as S12, S15 and S17. This group might evidence the most obvious learning effects of our online materials. Generally speaking, except for the ‘‘no change’’ group in category 1, students made improvement in reducing their use of general words and/or using more specific alternatives quantitatively. That is, in addition to higher scores in controlled tests, all the participants wrote essays of better quality after learning from the online materials. Since more target words surfaced in the posttest essays in our analyses, we could say that the participants were pushing up their diction use, though at idiosyncratic routes towards improvement. We can postulate that, compared with their word use on the controlled tests, in a free writing situation students paid much less attention to how words, particularly adjectives, should be used appropriately. When they were engaged in a writing task, they had to pay attention to many other aspects, such as generating ideas in a short time and organizing the ideas coherently, in addition to word use. Next, the actual use of target items in the two writing tasks completed in the pretest and posttest periods were compared and are shown in Tables 4 and 5. In the first batch, no specific adjective items had been used by students (see Table 5). Three general words—important, beautiful and big—were used frequently in student pretest 144 Y. Yeh et al. Table 5. E Students’ adjective use in the pretest essays General adjective use Word Instance Occurrence Important (3) It’s important to . . . . Stage 2 1 Beautiful(11) university/Tsing Hua Campus scene/scenery Place Landscape 4 3 2 1 1 big(3) Place Tree Tsing Hua 1 1 1 and posttest essays. Among these three general words used in the pretest essay, beautiful, which was used to describe the campus or the view in the university, had the most frequent occurrences. In the posttest essay, some students had tried to employ alternatives such as lovely, instead of beautiful, to describe ‘‘campus’’ and ‘‘scene’’. Another noteworthy instance was that students learned to use crucial as in the sentence, ‘‘it is crucial for a school to have the quality of humanity’’. The comparison evidenced that students used more specific adjectives such as crucial, significant, lovely, and pretty after learning through the online units. From the list in Table 6, it could also be inferred that the online units raised students’ awareness of avoiding overused and general items and trying out other specific words not taught in the online materials. To illustrate, with the concept of beautiful, we found that students were able to employ more specific adjectives which were not included in the online unit, for example, splendid/enchanting scene, picturesque environment/view and wonderful campus. After the completion of the learning units, students themselves were aware of looking for an appropriate substitute to express their ideas. In sum, students’ increased knowledge of synonyms and their appropriate use of target words was demonstrated in their free production. The comparison of the two essays revealed that the phenomenon of overuse was reduced. It was also found that the online synonym learning had raised learners’ awareness in avoiding overused items when they attempted to use not only the target words learned through the online units but also other specific adjectives not presented in the units. Learners’ Induction during the Instructional Process To examine what led to students’ improvement or non-improvement, process data recorded in the online tracker program while the participants were working on the exercises were examined. Students’ induction on the online summary page was 145 Synonym Units and Concordance for Writing Table 6. Students’ adjective use in the posttest essays General Word Specific Collocates Important (4) V-ing is important Quality Thing Reason Beautiful (21) Campus Scenery/scene Place Forest Surroundings Environment Lake Harmony Occurrence Word Tsing Hua Field Campus Building Occurrence 1 1 1 1 Crucial (3)* Role Decision it is crucial to . . . Significant (1)* Mark 1 1 1 1 10 4 2 1 1 1 1 1 Splendid (1) Lovely (2)* Scene Campus Scene Campus Lake Tsing Hua Environment View Scene Scenery 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 Campus Campus Part Size 1 3 2 1 Wonderful (1) Pretty (1)* Picturesque(4) Enchanting (1) Gorgeous (1) Big (5) Collocates 2 1 1 1 Great (1)* Large (5)* Huge (1)* Note: *indicates synonyms included in the online units. checked against the illustrations in WordNet or A modern guide to synonyms (Hayakawa, & The Funk & Wagnalls Dictionary Staff, 1969). Table 7 shows the number of students who successfully induced patterns for each synonym (see an example of students’ induced patterns in Appendix B). Overall, the inducing task was a challenging one for this group, but on average the accuracy rate of all five units reached 0.59, over half of the cases, across the 30 target words for the 19 participants. It was found that in unit 2, there were more successful tries in induction (N ¼ 66, accuracy rate ¼ 0.69) than in the other four units, while unit 3 had fewest (N ¼ 45, accuracy rate ¼ 0.47). The success rate for induction may be common in an educational setting where the deductive approach, instead of data-driven learning, had been the norm for the participants in their six years of high school study in Taiwan. For unit 2, students did quite well in indicating the types of nouns following the synonyms of beautiful. However, the words in unit 3 were of greater difficulty when students were required to find the differences among the synonymous words. This was especially obvious with words such as challenging and rough. Moreover, it was observed from the tracker record that students did not recognize that pretty was synonymous with beautiful and rough with hard. In fact, two of the students simply presented pretty with the meaning of ‘‘rather’’, and rough with the meaning of ‘‘not smooth’’. On average, the accuracy rate of induction throughout the five units for the 19 participants reached 0.59, barely over half. Perhaps due to unfamiliarity with 146 Y. Yeh et al. Table 7. Numbers of appropriate induction about the five units based on participants’ process data Overused adjectives Alternative words Number Sub/total Unit 1 important Critical Crucial Influential Serious Significant Vital 14 13 10 9 11 Unit 2 beautiful Charming Good-looking Handsome Lovely Pretty 12 14 12 17 11 66/95 (0.69) Unit 3 hard Challenging Problematic Rough Tricky Tough 8 11 6 10 10 45/95 (0.47) Unit 4 big Enormous Huge Large Great Vast 12 13 10 14 10 59/95 (0.62) Unit 5 deep Bottomless Heavy Intense Profound Strong 9 11 11 13 10 54/95 (0.57) 57/95 (0.6) inductive data-driven learning or because of the specific educational culture in Taiwan, the participants, similar to those in Yeh (2003) or Chan and Liou (2005), were not good at using data to find patterns or at spending time in testing their own original interlanguage hypothesis. They also showed various success rates of appropriate induction possibly due to either the inherent association strengths of the AN collocations or to the artifact effect of item difficulty. Learners’ Perception of the Five Online Units The data from the background questionnaire, the evaluation questionnaire and interviews were coded and analyzed to reveal students’ feedback on the online units. In the responses to the evaluation questionnaire, around half the students (52.6%) reported that they liked the synonym learning, 36.8% held a neutral attitude and 10.5% of the students responded with a negative attitude. Half of the students (53.1%) found it difficult to make distinctions among semantically similar words. Similar to findings of previous studies (e.g. Chan & Liou, 2005; Yeh, 2003), a great Synonym Units and Concordance for Writing 147 majority of students (72.7%) indicated that it took much time to analyze corpus data. Merely 31.6% of the students reported that the instances of the AN collocates provided by TANGO were sufficient to differentiate the synonyms, while about half of the class (47.4%) held neutral opinions. Student’s feedback on this item was beyond the researchers’ expectations because one of the researchers, having been in a college English program for six years throughout her undergraduate and graduate studies, had examined the AN collocates in TANGO to make sure the instances provided in the online materials were sufficient for the participants to induce patterns. The students who participated in the study, however, were in their first semester of a college English program and therefore may have found it difficult to make successful inductions out of the instances provided in the online materials. This conflicting result seems to hint that adequate English proficiency is one key element for successful induction. How to effectively scaffold weaker learners in their induction process with e-referencing tools such as TANGO or other bilingual concordancers warrants future research. Specifically on the usefulness of TANGO, the participants mostly (73.7%) agreed that mutual translations in the Chinese – English bilingual concordancer helped them learn English synonyms effectively. It seems that TANGO was more effective than other regular print dictionaries. The observation made in the current study that synonym search using traditional print materials was unsatisfactory to the participants was compatible to the study by Harvey and Yuill (1997) in which synonym searches with a dictionary were considered unsuccessful by EFL learners. The researcher also interviewed the participants after the immediate posttest. For the improvement of the online units, students indicated that the system was sometimes unstable and there should be a clear leave-taking message after they completed the exercises. Students also recommended that online units include other types of collocations, such as Adv – Adj, for word search. Conclusion and Implications The current study investigated whether online units could increase EFL learners’ awareness and application of synonymous adjectives. Nineteen college Englishmajors in a freshman writing class participated in the study. The major findings indicate that students made significant improvement in synonym use in the controlled tests and still maintained that knowledge two months after they completed the online learning units. It was also found, from the comparison of the pretest and posttest essays, that the participants improved their overall writing quality and performance in the use of synonymous adjectives. The participants were able to induce some patterns for the target words of 30 synonyms with various degrees of success. On average, the accuracy rate of induction was over 50%. Students’ feedback showed that they did benefit from concordancing learning though it was somewhat difficult and timeconsuming to discover the differences among synonymous words. In light of the findings, some pedagogical implications can be drawn for EFL teachers and researchers. First, the collocation concordancer, TANGO, could be used for facilitating vocabulary learning since it offers appropriate AN collocations 148 Y. Yeh et al. and provides alternative words for writing. In teaching, teachers could present semantically related words and concordance lines from TANGO so students could benefit from comparing and contrasting the synonyms in context. Teachers could also pinpoint the differences between words if induction turns out to be too difficult for most students. For learners’ self-instruction, TANGO could serve as a consulting tool for them to search through possible collocates for a proper alternative adjective for use. Further, students can be encouraged to check specific collocates that go with a certain synonymous adjectives, which they already have in mind for use, so as to serve their purpose in speaking or writing. By so doing, appropriate adjectives with collocates could be found for the appropriate context in speaking or writing. Second, teachers should consider designing other types of in-class activities to enhance vocabulary learning, particularly for the words challenging and rough, when the online materials are not effective enough. The learning units in this study do not seem to be so effective for learning the synonyms of hard and big; that is, the induction task and the practice provided in our online materials seems insufficient for students to acquire the words. Therefore, teachers could provide patterns or hints of word use for hard and big, or ask students to make their own sentences out of the words for further practice and discuss them in class for clarification. Finally, students need thorough training in induction skills before they begin to study corpus data. Some participants made complaints that inductive learning was challenging but they did not know what they should put down for distinguishing the subtle differences on the summary page. As traditional teaching methods in Taiwan emphasize deductive teaching, students lack the experience of discovering patterns or rules from authentic language data. Consequently, more guidance should be offered by teachers if concordancing is to be incorporated into the EFL curriculum. The small number of participants was one major limitation of the study. For future research, more participants could be invited so that the result can be generalized to other populations of English learners with different backgrounds. Also, with regard to the size of the learner corpus collected for analyses, more writing should be collected in the future in order to elicit additional data on students’ adjective use in free production. At this writing, more student essays were being collected in this EFL country; given careful error tagging, useful information can be yielded from a large learner corpus for the future. Moreover, a longitudinal study could be conducted to observe students’ word use over a longer duration since students might need more time before they could acquire semantically similar words and apply them in actual writing. In that case, better vocabulary measurement is needed to gauge students’ productive use of synonyms in writing. Acknowledgement This paper is sponsored by the National Science Council in Taiwan (NSC94-2524S007-001). Thanks go to Jason S. Chang and his graduate students for development of TANGO. Synonym Units and Concordance for Writing 149 References Bialystok, E., & Sharwood-Smith, M. (1985). Interlanguage is not a state of mind: An evaluation of the construct for second language acquisition. Applied Linguistics, 6, 101 – 117. Chambers, A. (2005). Integrating corpus consultation in language studies. Language Learning & Technology, 9(2), 111 – 125. Retrieved 14 August 2005 from http://llt.msu.edu/vol9num2/ chambers/default.html Chan, T. P., & Liou, H. C. (2005). Effects of web-based concordancing instruction on EFL students’ learning of verb – noun collocations. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 18(3), 231 – 250. Engber, C. A. (1995). The relationship of lexical proficiency to the quality of ESL compositions. Journal of Second Language Writing, 4, 139 – 155. Flowerdew, L. (2001). The exploitation of small learner corpora in EAP materials design. In M. Ghadessy, A. Henry, & R. L. Roseberry (Eds.), Small corpus studies and ELT: Theory and practice (pp. 123 – 132). Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Granger, S., & Tribble, C. (1998). Learner corpus data in the foreign language classroom: Formfocused instruction and data-driven learning. In S. Granger (Ed.), Learner English on computer (pp. 199 – 209). London & New York: Addison Wesley Longman. Gui, S., & Yang, H. (2002). Chinese learner English corpus. Shanghai: Shanghai Foreign Language Education Publishing. Ham, N., & Rundell, M. (1994). A new conceptual map of English. In W. Martin, W. J. Meijs, M. Moerland, E. Ten Pas & P. G. J. Van (Eds.), Proceedings of the 6th Euralex International Congress on Lexicography (pp. 172 – 180). Amsterdam: Vrije Universiteit. Harvey, K., & Yuill, D. (1997). A study of the use of a monolingual pedagogical dictionary by learners of English engaged in writing. Applied Linguistics, 18(3), 253 – 278. Hayakawa, S. I., & the Funk and Wagnalls Dictionary Staff (Eds.). (1969). Modern guide to synonyms and related words. New York: Funk & Wagnalls. Horst, M., Cobb, T., & Nicolae, I. (2005). Expanding academic vocabulary with an interactive online database. Language Learning & Technology, 9(2), 90 – 110. Retrieved 14 August 2005 from http://llt.msu.edu/vol9num2/horst/default.html Hunston, S. (2002). Corpora in applied linguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Jacobs, H. L., Zinkgraf, S. A., Wormuth, D. R., Hartfiel, V. F., & Hughey, J. B. (1981). Testing ESL composition: A practical approach. Rowley, MA: Newbury House. Jian, J. Y., Chang, Y. C., & Chang, J. S. (2004). Collocational translation memory extraction based on statistical linguistic information. Paper presented in ROCING 2004, Conference on Computational Linguistics and Speech Processing, Taipei. 11 – 12 September. Johns, T., & King, P. (Eds.) (1991). Classroom concordancing. Special Issue of ELR Journal 4. University of Birmingham: Centre for English Language Studies. Johnson, D. D. (2000). Just the right word: Vocabulary and writing. In R. Indrisano & J. R. Squire (Eds.), Perspectives on writing: Research, theory, and practice. Newark, DE: International Reading Association. Keller, G., & Warrack, B. (2002). Statistics for management and economics. Belmont, CA: Duxbury Press. Lee, C. Y., & Liou, H. C. (2003). A study of using web concordancing for English vocabulary learning in a Taiwanese high school context. English Teaching & Learning, 27(3), 35 – 56. Martin, M. (1984). Advanced vocabulary teaching: The problem of synonyms. The Modern Language Journal, 68(2), 130 – 137. Miller, G., Beckwith, R., Fellbaum, C., Gross, D., & Miller, K. (1993). Introduction to Wordnet: An on-line lexical database. International Journal of Lexicography, 3(4), 235 – 312. Partington, A. (1998). Patterns and meaning: Using corpora for English language research and teaching. Philadelphia, PA: John Benjamins. Ringbom, H. (1998). Vocabulary frequencies in advanced learner English: A cross-linguistic approach. In S. Granger (Ed.), Learner English on computer (pp. 41 – 52). New York: Longman. 150 Y. Yeh et al. Santos, T. (1988). Professors’ reaction to the academic writing of nonnative speaking students. TESOL Quarterly, 22(1), 69 – 90. Sinclair, J., Hanks, P., Fox, G., Moon, R., Stock, P. (Eds.). (1987). Collins COBUILD English Language Dictionary. London: HarperCollins. Sun, Y. C., & Wang, L. Y. (2003). Concordancers in the EFL classroom: Cognitive approaches and collocation difficulty. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 16(1), 83 – 94. Tschichold, C. (2003). Lexically driven error detection and correction. CALICO Journal, 20(3), 549 – 559. Wray, A. (2002). Formulaic language and the lexicon. Cambridge: Cambridge Press. Wu, J. C., Yeh, K. C., Chuang, T. C., Shei, W. C., & Chang, J. C. (2003). The role of natural language processing in computer assisted language. In Tamkang University (Ed.) Proceedings of International Conference on ELT and E-learning in anEelectronicAage. Taipei: Tamkang University, 28 – 29 May. Yeh, Y. L. (2003). Vocabulary learning with a concordancer for EFL college students. In English Teachers’ Association (Ed.), Proceedings of 2003 International Conference on English Teaching and Learning in the Republic of China (pp. 467 – 476). Taipei: The Crane Publishing Company. Appendix A Samples of Exercises in the Online Units A. substitution practice (direction: ‘‘Please fill in a word that could replace ‘important’ In the sentence’’; The button: ‘‘submit my answer’’) B. gap-filling practice (direction: ‘‘Please fill in the required number of synonyms to make the sentence a complete one’’; The button: ‘‘submit my answer(s)’’) Synonym Units and Concordance for Writing 151 C. translation practice (direction: ‘‘Please translate the following sentence into English and use the most specific adjective’’; The button: ‘‘submit my answer(s)’’) Appendix B An Example of Students’ Induction 152 Y. Yeh et al. The summary page The notepad Critical Nouns : moment, juncture, time Usages : a turning point. Crucial Nouns : factor, juncture, point, importance Usages : a decisive point. Influential Nouns : figure, group, member Usages : to describe something is effective and representative. Serious critical Sentences: critical acclaim Comments: : problem, crime, accident, shortage, loss, error : something is important because of possible danger or risk; hard to solve Significant Nouns : change, impact, increase, sum, number Usages : something has a meaning or important and considerable. Vital Nouns : organ, energy, part, function usages : extremely important, especial related to existence or life. crucial Sentences: This also gave rise to a crucial question: Comments: give rise ¼ question: influential crucial Sentences: influential group Comments: serious Sentences: serious study Comments: That’s mean study hard and want to make out something. significant Sentences: significant change Comments: a fast and huge change significant: vital Sentences: vital function Comments: This allows vital functions such as police services, customs, medical services and transportation services to continue to operate year round without a break.

© Copyright 2026