Lionheart: The True Story of England`s Crusader

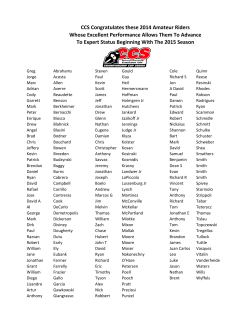

1 Lionheart: The True Story of England’s Crusader King (review by Garry Victor Hill) Douglas Boyd, Lionheart: The True Story of England’s Crusader King Stroud, Gloustershire; The History Press, 2014. At last a biography of Richard the Lionheart that the man deserves! That is not meant as a compliment. In Douglas Boyd’s Lionheart: The True Story of England’s Crusader King we get just what the title promises, but the truth emerges as distasteful. In the Western world Richard has had a generally good image. With the Richard the Lionheart of popular legend, culture and some biographies the virtues pile up on each other. Depictions usually focus on qualities. The most commonly applied adjectives are handsome, manly, steadfast, courageous, magnanimous, chivalrous, cultured, generous, honourable and courteous. He is presented as a brilliant military leader and wise administrator much concerned with his duty to the kingdom of England. His effigy and contemporary descriptions show that his admirers got handsome right, even if most of the other listed virtues were more celebrated than real. 2 There have been some exceptions to this hero worship. In James Goldman’s play The Lion in Winter (1966) and the subsequent film version Richard appears as a neurotic, mother dominated homosexual, up to his neck in the Plantagenet family’s web of treachery and ruthless scheming for power. At the start of Robin and Marion (1976) also written by James Goldman, Richard Harris gives a brilliant cameo of a petulant, tyrannical, self-pitying megalomaniac who gets himself killed through his greed. Arab culture presents Richard the way the West presents Attila the Hun or Genghis Khan. Although Richard worked on a smaller scale, the comparisons are essentially justified. Going by this biography, James Goldman got it right. Although he was born near Oxford in 1157, Richard spent little of his life In England. Almost all of the time he did spend there as king was concerned with raising finance and appointing people to carry out his wishes while he went elsewhere. Little of the money raised from England benefitted England: the taxes levied there paid for his problems overseas. The best known of these special taxes was the Third Crusade, preparations for that began as soon as he became king in 1189. The largest of the levies was for his ransom in 1193/1194. Even after that was paid he hit England again for another massive levy that gains little attention from historians. This last tax was to subdue with rebellious vassals in his French dominions and to continue his conflict with their sometime supporter and ultimately, his great rival, Phillip Augustus of France. It could be argued that Richard’s levies were necessary to maintain power, but he loved costly things, warfare, pageantry, banquets, celebrations and building castles. He was also extremely domineering, vain, greedy and warlike. Those four characteristics embodied in one man should come as no surprise, for what are wars but a way to dominate and by doing so, gain wealth and self-aggrandisement? What appears as unusual is that these characteristics were so intensely and obviously embodied in one man. This type usually have a sacred cause to justify their behaviour. Richard would eventually fall into this pattern with the crusade, but before and after the Third crusade he did much to reveal his true character. He continually rampaged across the lands of his father, his brothers, his neighbour’s or those of his vassals, killing and plundering on the slightest excuse. In Boyd’s account Richard died in one such adventure because one of his vassals found an ancient treasure on his property and when the vassal offered an even split of that find, an enraged Richard, wanting the lot and seeing the vassal’s refusal as 3 treason, besieged the vassal’s castle. There may have been mutinous aspects behind this as Plantagenet France was seething with intrigues, betrayals and conflict – as usual. Whatever the cause, Richard ended up slowly dying from an arrow wound. The incident that says it all about his greed and brutal murderousness was the murder of the hostages of Acre. He kept alive 300 of the most valuable hostages who had surrendered as part of a glorified extortion racket. He had 2,700 others murdered as negotiations over the requested ransom were stalling. Batches of men, women and children were systematically stabbed and bashed to death in front of Saladin’s people. Although Douglas Boyd does not explicitly say it, his description of this savage display was apparently so the more valuable would be ransomed. Hearing rumours that some of the dead had swallowed gold and jewels, Richard had their bodies cut open and searched. Even his executioners physically tired of the slaughter and asked for a respite. His involvement in this crusade shows not only his greed and brutality but his foolishness. Even though he was obviously heir to the kingdom of Henry II he had pledged to go on crusade a year before when his father was in good health, but was this wise? The Muslims had almost won a war against the Christian kingdom of Outremer, based around much of what is now Israel, Lebanon, Jordan and western Syria. Only a few sections along the Levant coast still held out. To regain that kingdom and recapture Jerusalem obviously meant a long conflict far away from his own restless kingdom - which assorted intriguers were already trying to usurp. There was also the track record of previous crusades. The First Crusade eventually won Jerusalem, but after four years of costly effort that devoured money, time and lives on a massive scale. The second crusade did the same, but for a disastrous outcome for the Christians, as Richard’s mother Eleanor of Aquitaine, one of the main participants, could have told him. A shrewder man would have sent his ambitious, treacherous and troublesome brother John to represent England on the crusade and stayed home, but Richard was a warrior. Richard loved warfare, but does that make him a great military leader? Despite his many victories in France his record in the crusade suggests not. Despite his courage, his high level of skill in organisational matters, his ability to inspire others and his high levels of skill and personal strength and energy, his track record in the crusade suggests he was over rated. He won the siege of Acre, but that had 4 been going on for years before his arrival in the Levant and he crushed an already weakened, starving and much reduced foe. There were also military defeats and long marches and counter marches, sieges for small advantage and inability to capture Jerusalem. He spent much time and energy feuding with other Crusaders. All these factors saw his army demoralised. His forces were whittled away by disease, heat and raids. He did win the battle of Asurf against Saladin, second only to Genghis Khan as the best military commander active at that time. There were also other victories, but the famous quote about Hannibal, that he knew how to win victories but he did not know what to do with them, applies to Richard. At one stage after defeating the Muslims, a quick dash to the still under defended Jerusalem could probably have taken the city, but Richard did not try that, even though from the initial planning onward the most important purpose of the Third Crusade was to capture Jerusalem. An inspiring figure on the battlefield with his personal courage and sedulous strength and energy, Richard worked against his own battlefield achievements in war councils. Always out for the money and prestige and control, he seems to have spent as much time arguing about such matters with the other Crusader commanders as he did fighting the Moslems. In one of his most foolish actions that had far reaching consequences he would not allow Leopold of Austria to hang his banners from the walls of captured Acre, fearing that this would give him credit and a right to some of the city’s booty. Leopold got his own back when Richard was forced to cross his lands and Leopold took him prisoner. Those who praise his military abilities seem to forget that the Third Crusade was a disaster for the Christians and as Richard had become its supreme commander he bears some responsibility. He did inherit a losing war, but he made his own unwise choices. Ultimately all he could do was prolong the conflict and get some concessions to go away. After heavy costs, massive losses and years of time all the Crusaders had for it was the retention of a few coastal cities, the right to go on pilgrimages to holy sites and a truce that was meant to last for three years. Richard even had his reputation for being a stalwart Christian Crusader tarnished. A Moslem assassin of the fanatical Hashashin sect claimed under torture that he had been paid by Richard to murder Conrad of Montferrat. Conrad had been the ally of Phillip Augustus and had the French king’s support to be the most powerful ruler of Outremer, while Guy de Lusigan, Conrad’s rival and enemy was 5 Richard’s candidate, despite having little capacity for leadership, respect among the Crusader lords or financial or military assets. Richard made mistake after mistake after mistake in the overall execution of the Third Crusade, starting with going on it. From the start of that war, two years before, it was evident that the Christians in the Holy Land lacked the unity, the numbers, the ability and the acumen to win the struggle by themselves. They would be weak allies to align with and their feuds would embroil all those who came into contact with them. The Crusade would need a trusted, strong, respected and wise leader to hold together the disparate Christian leaders if they were to succeed against a powerful, respected and successful enemy. Richard was obviously lacking in all those qualities: Saladin had all three qualities in abundance. Even before becoming king he had earned a reputation as a man to distrust. Some historians and writers say that his nickname ‘Richard yea or nay’ was because of his bluff, clear and direct answers and his expectation of responses in the same spirit. This nickname signified the honesty of the hearty warrior above Machiavellian politics. As Douglas Boyd shows, almost the opposite is the truth. He was nicknamed ‘Richard yea or nay’ because in diplomacy and governance he would give contradictory answers on the same day, break oaths almost soon as he had made them and almost immediately replace new appointees with others. Even by Medieval standards he was renowned for treachery, betrayal and greed. He had gone to war twice against his father, fought with his brothers in a bewildering series of alliances and double crosses and aligned himself with Phillip Augustus, perhaps in a homosexual relationship and then made him a lifelong enemy, before they made an uneasy alliance to go on crusade. These problems were all evident even before the Crusaders sailed. Even before reaching Outremer he became embroiled in feuds with other Christians, first in Sicily then in Cyprus. He could not even land for supplies without starting wars which left him richer but dissipated his military strength, created Christian enemies on his supply lines and made him a late arrival. It was also evident that leaving his kingdom to go on crusade would leave it open to being taken over. Even admiring historians criticize his decision to leave his brother John with as much power as he did, even allowing for power sharing with others. Douglas Boyd deals with a lesser known choice who was even more unwise. Chancellor Longchamp plundered England for whatever he could get and 6 how much acumen is needed not to put a known pederast like Longchamp in charge of aristocratic boys being held hostage? Or did Richard want to aggravate their parents into declaring war on him for some reason? In Douglas Boyd’s, Lionheart: The True Story of England’s Crusader King we are given a long chronicle of regal mistakes, foolish behaviour, arrogance, betrayals and atrocities. Others have also done that, but what differs in this account is that they are all put together in one work. The writer also does something different by going outside regal and noble circles to show how the ordinary people suffered and endured for this royal behaviour. Boyd shows us what living as a Medieval peasant really meant. They were starved so that the rich could eat abundantly. Boyd also shows what it was like to be a seafaring crusader taking months to reach the Holy Land living on putrid rations, and how women were used in a warrior’s world. With animals he shows how horses were treated while voyaging in cramped boats, and their fate in wartime. Even in peacetime it was a repressive world. At times he points out how are glamorised images of the medieval world are wrong. It was a horrible world and although in the long term the Crusades brought some benefits, particularly in trade, agriculture and knowledge, at the time they made the Medieval world much worse. The full extent of the disaster of the Third Crusade becomes evident when asking the question of how many other Crusaders ever returned home? The answer comes in comparing the start and the end. In March 1190 Richard went to the crusade with a massive and powerful army and a fleet of around two hundred vessels. In October 1192 he left the Outremer lands in a lone galley with a begged bodyguard of Templars. Within weeks he was trying to avoid capture from onetime fellow crusaders by a futile disguise as a scullion. That disguise does not rate highly as the deed of one named Lionheart: many of his other deeds also do not go with the popular image. Lionheart: The True Story of England’s Crusader King records many similar or worse instances. There are too many accounts of his battlefield courage to doubt it, but there was another side to this epitome of the warrior. Off the battlefield Richard’s behaviour goes directly against the warrior hero image. Richard the Lionheart, usually arrogance incarnate, indulged in weeping and self-abasement and was to a large extent, controlled by his mother. He seems to have had a masochistic streak to match his sadistic one, for he frequently wept in public when performing acts of repentance, acts of fealty, confessions of wrongdoing and assorted ceremonial acts. When 7 performing public fealty to the Holy Roman Emperor Richard apparently knelt and kissed the emperor’s feet while begging pardon. On two occasions religious hermits brought this mighty king to public penance, once in Sicily for sodomy and then in France in 1195 for general sinfulness. His mother decided when and who he should marry and perhaps was behind his wiser promotions and appointments. The most obvious were William Marshal, Walter Hubert and his nephew Otto. His defenders point to the reality that he was not a killing machine, he was much more than just a hearty warrior, he was a cultured patron of the arts, who enjoyed music, poetry and literature, true enough. John Gillingham in his Richard the Lionheart (1978) makes the point that Richard committed to go on the crusade before he was king and when his father was in good health; he did not abandon his kingdom for a crusader’s role. Once again this is true enough, but how much foresight was needed at that time to see the obvious way crusades unfolded? Gillingham also makes other points in Richard’s favour. Militarily he led from the front to inspire his troops, courageously sharing their risks. His military skills went far beyond being a just a front line fighting man. When in total charge in France his allocation of finance and resources, his military organisation, strategies and tactics were effective. If he did not resolve the succession issue a divorce of his childless wife would have cost him an alliance and he died unexpectedly. Gillingham points out that statements about Richard’s homosexuality rest on a few contemporary statements which are open to interpretation. If he did not govern England well he saw it as a lesser province in the Plantagenet Empire: the French provinces were his main focus. They had to be as they were almost continually under attack or the target of French intrigues. After his return in 1194 he not only stopped the military advances of the French who had been devouring the Plantagenet possessions, (and would do so again soon after his death) he added more French territory to the empire than had existed before his father’s death. He was wisely magnanimous upon his return to England, avoiding civil strife. In Gillingham’s account based on primary sources the 1199 conflict that led to his death, the refusal to obey him and to hand over the treasure was more than disobedience. This was treason and several of his French vassals were apparently already aligning with Phillip Augustus or secretly intriguing to do so and this could not be tolerated. He was putting down a rebellion, not just going on a looting spree. Richard’s continuance of his father’s wise legislation concerning laws and legal rights after his return from the crusade improves his image. They were 8 certainly fair and beneficial laws, but that is giving Richard the credit for what Walter Hubert did and administered. Richard deserves credit for not blocking those changes. This example leads to a question about how we construct history. To what extent are regal figures responsible for the events that unfold in their reigns? Are they almost godlike creatures directing their lands as they wish, either wisely or foolishly? Or are they more like modern politicians, continually doing a balancing act between forces they cannot really tame or even control for very long but must placate to stay in power? Richard as the epitome of knightly courage in this heroic image. Here he defends the British Parliament. One of England’s worst rulers got one of its best statues in the best possible locales. Douglas Boyd’s book suggests that the legendary Richard is still seen as being in the first category and that this image of the warrior hero is his strength. It is also the source for his continuing popularity in culture. Reality can only be another matter: he was in the second category and was disastrous in the role. 9 We are not so different from the mentality of the medieval crusaders. They bought holy relics from hucksters; our post offices sell us phials containing sand from the beaches of Gallipoli. They went on crusade to save the Christians of Outremer; we fly to the Middle East to save the ethnic minorities, some like the peoples of Outremer are Christians under threat from Moslems. The belief in good guys verses bad guys in the East continues, perhaps that remains a reason why we need the image of the earlier Western hero in the Middle East. If there are any heroes there they may be among the medical staffs of the Red Cross, the Green Crescent and Medicines Sans Frontiers. Victims do need saviours, but saviours equipped with needles, not knives. We judge Richard’s embroilments in Eastern conflicts as foolishness, but in the eight hundred years since his death more examples of the West going to war in the East have piled up and most have been disasters. Even when they are victories such as the victory against the Ottomans in 1918, they lead to problems that fuel future disasters. * The effigy of Richard I on his tomb at Fontevraud Abbey

© Copyright 2026