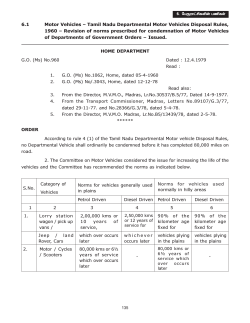

The Uses of Norms