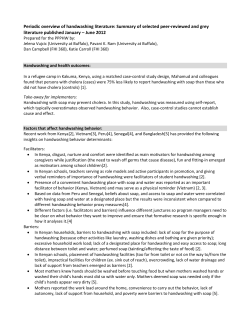

Handwashing behavior in Humanitarian Emergencies: The Experts