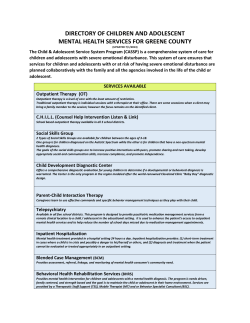

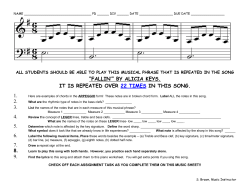

Action Research: Improving my music therapy practice with