pdf click - International Journal of Migration Research and

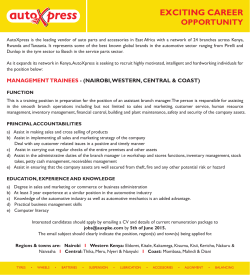

International Journal of Migration Research and Development (IJMRD) www.ijmrd.info, Volume 01, Issue 01, Summer 2015 Rural-Urban migration: An empirical study of socio-cultural situation on slum dwellers of Nairobi in Kenya Salim Neema1 Abstract Rural-urban migration and poverty is the most common phenomena for the developing countries. The research was longitudinal research platform, set up in Korogocho and Viwandani slum settlements in Nairobi city, Kenya. Findings provide migration status interacts with health issues over the life course. Contrary to popular opinions and beliefs that see slums as homogenous residential entities, while slum migrants especially women and children are recordable mobile, about majority of the community comprises relatively well doing long-term dwellers that have lived in slum settlements for over 15 years. The poor migrants women and children outcomes that slum residents exhibit at all stages of the life course are rooted in five key characteristics of slum settlements: poor environmental conditions and infrastructure; limited access to services due to lack of income to pay for treatment, lack of limited, healthy and unhygienic food consumption, lack of cleanliness and hygienic practice and knowledge and mostly informal and unregulated services that are not well suited to fullfill the unique realities and basic needs of slum dwellers Keywords: Rural-urban Migration, Poverty, Slum, Women and children 1 Department of Sociology and Social Work, University of Nairobi, Email: [email protected] SALIM NEEMA 105 International Journal of Migration Research and Development (IJMRD) www.ijmrd.info, Volume 01, Issue 01, Summer 2015 Introduction Migration is the demographic process that links rural to urban areas, generating or spurring the growth of cities. The resultant urbanization is linked to a variety of policy issues, spanning demographic, economic, and environmental concerns. Growing cities are often seen as the agents of environmental degradation (White, 1999. Migration is a relevant phenomenon with important implications at three different levels: local, regional and international. On the wider level, migration is tightly related with globalization and with the workflow of human resources towards the host countries; on a local level, rural to urban migration is one of the most important aspects of the economy of the state. Migration is an important aspect of globalization and has implications on local, regional and international development. Women and children are vulnerable segments of population almost in every part of the world. It is also true for Bangladesh because of its social inequality, un favourable economic condition, political climate, joblessness etc. The large-scale migration of women and children to urban areas is not entirely a recent phenomenon, nor is it equally common in all parts of the world. In Asian context women have many outstanding characteristics, such as their industrious, dutiful, conscientious and intelligent personalities, but most of all their roles in keeping the society in stable development (Farhana, 2011). High rates of urban growth that have unfolded in the context of stagnating economies and poor planning and governance have created a new face of abject poverty concentrated in informal settlements, commonly referred to as slum settlements or slums, in Africa’s major cities. Recent estimates by UN-Habitat show that sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) is the only region where no tangible progress has been made in improving the lives of slum dwellers in line with the targets set under the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) framework. While the proportion of urban residents living in slum settlements has declined from 70% to 62% between 1990 and 2010, the actual number of slum dwellers has doubled from 103 million to 200 million over this period.1 Slum settlements are characterized by poor housing conditions, poor social services, poor basic amenities, poor health outcomes, insecurity, and unstable incomes and livelihoods. If these patterns and trends continue unchecked, the region’s socioeconomic prospects will increasingly be determined by the lives of the urban poor since urban areas will continue to grow faster than rural areas in SSA (Zulu et al 2011) According to Dweks (2004) as quoted by Mowforth (2008), people are living in an increasingly urbanized world and this is likely to accelerate rather than reverse the growth of slums. In 2006 a report by the United Nation’s city agency (UN-HABITAT) confirmed that the global urban transition is only at mid-point with projections showing that over the next 25 years the world’s urban population is set to increase to 4.9 billion people by 2030, roughly 60% of the world’s total population (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs 2006). Moreover, the most significant growth is projected to occur in less developed regions with sustained and rapid increases culminating in 3.9 million urban dwellers in these regions by 2030 (United Nations Department of Economics and Social Affairs, 2006). In Kenya, nearly 60% of Nairobi's population live in slums. In the Mukuru slum, in the East of Nairobi, an EU funded project is helping to improve the health status of residents through the provision of water and sanitation facilities. It is said that "water is life and sanitation is dignity". However, this dignity is missing throughout most of the Mukuru slums. With a staggering population of over 600 000 people, the sanitation conditions in the Mukuru slums almost constitute a humanitarian crisis. Basic sanitation SALIM NEEMA 106 International Journal of Migration Research and Development (IJMRD) www.ijmrd.info, Volume 01, Issue 01, Summer 2015 facilities such as: basic drainage, waste disposal facilities and clean water supply are almost nonexistent. Also Kibera is the biggest slum in Kenya. Most of the residents are casual labourers who earn 100 shillings or less per day. They engage in low income economic activities such as art, dance, drama, sports projects, self-help About 60% of the youths below 21 years are illiterate or semi-literate, majority have primary education only, Lack of jobs is the main problem and has led to social ills such as alcoholism, drug abuse and crime. About 80% of the population is either infected or affected by the AIDS scourge (Funke, 2008). Slums lack clean drinking water, proper plumbing, and access to health care facilities, poor electrification and other public services such as schools. groups and small scale businesses (CSG Kibera, 2007).According to Mowforth (2008), the intention was to eradicate the slums in Kenya as a long term procedure to reducing poverty by engaging the poor to participate more effectively in development sector in Kenya and by increasing the net level of living and environmental condition as a short term measure to the slum community. Methodology The study adopted descriptive survey research design. It entailed a description of the state of affairs based on information collected after administering questionnaires. This information was useful in highlighting the characteristics of poor migrants in Nirobi city participating in this form of migration, so that it can guide decision on the kind of market segment to be targeted in the process of participate obseving slum dwellers . It was also useful in identifying the product characteristics whose combined effect is the overall experience on the health-hygien environment of slum dwellers. The data collected from this research was basically qualitative and quantitative both methods used. The qualitative data focused on such areas as response on the people’s attitudes and opinion on issues and quantitative data focused on the economic, occupational and socio-demographic information. Around 200 (etch slum 100 family) sample data were collected through the observation and survey methods. The program’s overarching research aim was to examine the dynamic inter-linkages between migration, poverty, and ill-health in the slum setting. Additionally, the program sought to investigate whether these linkages vary at different stages of the life course namely, childhood, adolescence, adulthood, and old age. In particular, the study sought to investigate whether the people who move to slum areas are responding to life crises that have had deleterious impacts on their health or whether it is slum residence itself that has adverse consequences on the health and well-being of the residents. The program validated the relevance of various measures of poverty in informal urban settlements and sought to identify the most appropriate indices for understanding the inter-linkages between poverty and health outcomes over time and across the life course. SALIM NEEMA 107 International Journal of Migration Research and Development (IJMRD) www.ijmrd.info, Volume 01, Issue 01, Summer 2015 Discussion According to World Bank (2006, p.23), the poverty in urban areas by various socio-economic characteristics, the 2005/2006 KIHBS shows that the prevalence of poverty (34% total) among male headed households is significantly lower (30%) than female-headed households (46%). In turn, marriedfemale headed households in urban areas have a lower incidence of poverty compared with femaleother households (‘female-other’ signifying single, separated, divorced, or living together women). These latter households are among the most vulnerable in urban Kenya and suffer disproportionately from inadequate housing. In relation to age, 48% of households with the head aged 56+ years are poor, as compared with just around 23% in cases where the age group of the household head is 16-30 years. In Nairobi itself, comparative indicators on the population living in the city’s informal settlements can be drawn from a World Bank study based on a household sample survey of 1,746 households from 77 informal settlement enumeration areas. As shown in Table 1, there are more males than females, the ratio being 54:46, with a greater proportion of both school-age children (6-15) and adults (defined as 15 years or more) being male (50% and 57% respectively). The ethnic composition of Nairobi’s slum population can be quite diverse, though two or three tribes generally dominate in each settlement. Depending on a particular settlement’s location within the city, the main tribes are Luo, Luhya, Kikuyu, and Kamba. Ethnic allegiances can provide a source of cohesion within the community amongst those of the same tribe. However, such diversity of traditions and cultures can lead to conflict, particularly in situations when people are competing for limited resources or have to deal with contentious issues. The consequences can be dire, as the response to the contested presidential election results in December 2007 demonstrated: violence took on an ethnic character and led to large numbers of fatalities, as well as the displacement and destruction of property and livelihoods. Kibera, Mathare and Dandora informal settlements were the conflict ‘hot spots’ on this occasion. Feelings of insecurity have considerably heightened since that time and, while there is not yet adequate research into the present situation, anecdotal evidence suggests that slums have become increasingly ethnically polarised. With mobility being a facet of urban life, the tendency for ethnicity to denote one’s identity or status appears to have increased. An informal settlement tends to be dominated by one or two ethnic groups, usually reflecting its historical development and the ethnicity of the original inhabitants. Ethnic allegiances can provide a source of cohesion within the community amongst those of the same group. However, as was evident in the post-election violence in urban areas, ethnic identity – while capable of providing valuable social networks and reinforcing solidarity – can be used destructively and divisively. Associations and ceremonial cults based on ethnic membership drawn from urban society as a whole and often, in turn, connected with competition for employment or trade, are particularly evident in urban Kenya. These cults are manifested as Mungiki (Kikuyu cult), Talibans (Luo cult), and Jeshi la Mzee (Kalenjin cult) among others. It is groups such as these that wreaked havoc and destruction in a number of the informal settlements of Nairobi. SALIM NEEMA 108 International Journal of Migration Research and Development (IJMRD) www.ijmrd.info, Volume 01, Issue 01, Summer 2015 Figure 1: Age of Kebira and Muku slum dwellers 36 36 Kebira Mukuru 7 6 25 22 21 16 11 10 7 3 >20 years old 20-29 years old 30-39 years old 40-49 years old 50-59 years old 60-above years old It is anticipated that the bulk of jobs to be created in the foreseeable future will continue to be in the informal sector. Informal sector activities, which dominate in urban areas, are classified into the following categories (which broadly reflect the categories used in the formal sector): wholesale trade, retail trade, hotels and restaurants; manufacturing, industry; community, social and personal services; transport and communication; and construction. Nairobi itself is an international, regional, national and local hub for commerce, transport, regional cooperation and economic development. It connects eastern, central and southern African countries. It is likely that the majority of households rely on only one wage earner. Although female-headed households are significantly less likely to have a member with a wage-paying job than male-headed ones, a much higher proportion of them operate household micro-enterprises. The most common microenterprises found in the informal settlements fall into the following broad categories: (i) Retailing and food services including trading/hawking/kiosks and food preparation and sales; (ii) Small manufacturing/production, construction, and repair of goods (popularly known as jua kali);34 (iii) General services such as hairdressers, laundry, transport, medicine, photo studios; (iv) Entertainment services, including bars, brewing and pool tables. SALIM NEEMA 109 International Journal of Migration Research and Development (IJMRD) www.ijmrd.info, Volume 01, Issue 01, Summer 2015 Figure 2: Work Pattern or occupational sector of slum dwellers in Nirobi 9% 6% 33% retailing and food services including trading/hawking/kiosks and food small manufacturing/production, construction, and repair of goods 10% general services such as hairdressers, laundry, transport, medicine, photo entertainment services, including bars, brewing and pool tables 16% Prostutution 26% Others Diseases of Slum dwellers The poor environmental factors highlighted above predispose slum inhabitants to particularly poor health, and consequently they suffer from a high incidence of communicable diseases such as tuberculosis, diarrhoea, malaria and other waterborne diseases, as well as malnutrition. These factors in turn result in very high infant and child mortality rates. Such problems are exacerbated by the fact that the urban poor also find it difficult to access drugs from health clinics or chemists to treat preventable diseases, leading to high levels of inadequately treated morbidity. Child health is perhaps one of the most poignant indicators of vulnerability amongst the urban poor. The same study found that less than half the children in slums had been fully vaccinated against diseases such as Polio, malaria, diarreah, malnutrition etc is the common fiture of slum livelihoods. The HIV/AIDS prevalence rates also massively increase susceptibility in TB. In Nairobi, TB cases have increased sevenfold in the last decade and according to one report ‘today, there are more TB cases in Nairobi, with a population of 3 million, than in the entire United States. SALIM NEEMA 110 International Journal of Migration Research and Development (IJMRD) www.ijmrd.info, Volume 01, Issue 01, Summer 2015 Figure 3: Major diseases of both slum dwellers others HIV/AIDs 6% 3% coughf and feaver 29% TB 7% Dihirriea 10% Malnutision 22% Sckin allaergy 23% HIV/AIDs TB Dihirriea Sckin allaergy coughf and feaver others Malnutision Access to water In the informal settlements where the majority live, only 32% of households have water connections serviced by the Nairobi City Water & Sewerage Company (NCW&SC) and rest of the majority (68%) do not have legal access of water pipe line. They using water illegal pipe line or some time from road side or local NCW&SC’s general water supply through big raw for collecting water. Some of drinking water purchasing water from water kiosks or other water delivery services, as figure 08 shows the indicates. There found that only few of slum dwellers in Nairobi have piped water supplies, and majority of households complained of water shortages and pipes often running dry season. The public taps service are not sufficient for whole slum dwellers. Private entrepreneurs, who often operate as cartels charging high prices for water, usually run water kiosks. In Kibera, the price of water in 2005 was Ksh. 2 per cubic metre, which was eight times the lowest block of the tariff for domestic connections via NCW&SC and four times higher the average tariff in Kenya at that time.40 Illegal connections to the piped water supply are common, posing a major health challenge to the residents due to the compromised water safety. SALIM NEEMA 111 International Journal of Migration Research and Development (IJMRD) www.ijmrd.info, Volume 01, Issue 01, Summer 2015 Figure 4: Access of drinking water Access of drnking water 32% Do not have sufficient access of drinking water 68% Access to sanitation Approximately half the city’s total population have access to a flush toilet, and the vast majority of these are in the city’s wealthy and middle-income areas. By contrast, in the slums the majority of the residents use pit latrines that are over-used and inadequately maintained. In most cases, the latrines are not ‘on plot’ facilities but communal ones that serve a large number of people from the surrounding area. Individual pit latrines commonly serve 180 people per day. In some case usage is even heavier; during the study of Mukuru in Nairobi found that on average, there were about 300 people to each toilet. Where there is a high volume of users, the latrines become full very fast. Slum dwellers often have to resort to manual extraction of the effluent since exhaust services are limited, with the effluent then being emptied into the rivers passing through the settlements. Where cartels have taken over the management of latrines, user charges are high and unaffordable. As a result of such poor sanitation facilities, many slum-dwellers resort to the use of plastic (UN Habitat, 2003a 40 World Bank, 2005 41 UN-HABITAT, 2006 42 WSUP Scoping Study Report, Gatwekera, 2007 43 UN-HABITAT 2003a) carrier bags as toilets, which are then randomly discarded (usually referred to as ‘flying toilets’). Respondents in the both slums 77% of said that they do not have toilet facilities and only 23% have toilet facilities in the slum of Nirobi. SALIM NEEMA 112 International Journal of Migration Research and Development (IJMRD) www.ijmrd.info, Volume 01, Issue 01, Summer 2015 Figurer 5: Availability of toilet facilities in both slum Access to electricity The same study also shows that only few slum households have access to an electricity supply, which is generally used for lighting purposes. Some of these households access electricity through illegal connections. Among those households just 32% of them said that they have legal connection of electricity but majority of them said due to lacking access of electricity approximately 53% of respondent have access electricity through illegal connection, and 15% of them using through others sources such as kerosene is the primary source of Iighting as well as serving as the primary cooking fuel for most of the slum households overall. Charcoal is the next most commonly used fuel, with the attendant adverse impact on their health and the environment. SALIM NEEMA 113 International Journal of Migration Research and Development (IJMRD) www.ijmrd.info, Volume 01, Issue 01, Summer 2015 Figure 6: Access of Electric lighting facilities 15% 32% have legal elictric cunnection have illegal elictric cunnection 53% Do not have elictric cunnection Drainage system of slum areas In Kabira and Mukuru slums, proper drainage systems are rare; instead inadequate, hand-dug channels carrying untreated wastewater often blocked with rubbish are commonplace. the wealthy neighbourhoods and the central business district), refuse disposal and management is a city-wide problem – but it is of particular concern in the informal settlements. In the study slums, 73% respondent mansion they do not have any sewerage or drainage system through their household. Only 27% of respondent said they have access of drainage but due to clean and maintenance those are also overloaded and flourished bad smile and populate the slum environment. Figure 7: Drainage facilities through the both slum areas Have good dranage system for sowarage 27% Do not have proper drainage and sowarage system 73% SALIM NEEMA 114 International Journal of Migration Research and Development (IJMRD) www.ijmrd.info, Volume 01, Issue 01, Summer 2015 Crime and human insecurity The housing conditions of the urban poor are often deplorable. The informal settlements, of which it is varying considerably in terms of their population size and area, occupy few percent of the total residential land of the city despite housing over half of the population. In these a high percentage of the dwellings are constructed of semi-permanent materials, and many of them are severely dilapidated and over-crowded. In Kibera population density has been recorded as 826 persons per hectare. When slums are disaggregated even further the figures can become even more shocking: in Huruma slum, one area (Kambi Moto) recorded densities of 1,347 people per hectare and another (Ghetto) a remarkable 2,309.59 Proper accessibility, to allow for the free flow of goods and services into and out of the slums, is also lacking. When it rains in Kibera, residents are often forced to walk through mud and sewage for up to 3 kilometres before they can even get a bus to work. Meanwhile the lack of roads means the police are reluctant to enter, making the environment even more conducive to crime. Moreover, as tenants, households have no titles over the land on which the structures are built, and live under the threat of eviction either by the government or by private developers. This limits them from enjoying their rights as urban citizens. This fear of eviction and/or demolition of their structures by authorities or by their landlords is pervasive in low-income areas. Here with our study we find bellow listed threats and criminal records of slum dwellers livelihoods in Nirobi. Hijacking Crime and incequrity Robbery Kidnapping Rape / women abusing Killing, fighting others SALIM NEEMA 115 International Journal of Migration Research and Development (IJMRD) www.ijmrd.info, Volume 01, Issue 01, Summer 2015 Threats of Eviction from the slum By Government By Developer By Mafia Conclusion There is now evidence to suggest that the quality of life for the poor in some urban areas of developing countries is even worse than in rural areas. While the realities of the informal economy mean that it is hard to establish reliable figures about exact income levels in cities, there can be little doubt that poor urban-dwellers are subject to a particularly wide range of vulnerabilities. One over-riding conclusion has been reached: that poor urban governance in respect of planning and managing the affairs of the Nairobi city is a major driving factor of urban poverty and vulnerability. This therefore constitutes the core problem to be addressed. As the key actor in planning and managing the affairs of Nairobi, the performance of the City Council of Nairobi has been severely constrained. The above main conclusions point to a number of opportunities that are available through which support to urban poverty reduction could be provided. These points to a number of recommendations that are presented below together with some of the avenues through which each opportunity could be pursued. There is ample evidence globally to demonstrate that the practice of good urban governance can contribute towards reducing poverty. Given the inter-related dimensions of poor governance in Nairobi outlined above, the promotion of good urban governance in the city could be pursued through various avenues SALIM NEEMA 116 International Journal of Migration Research and Development (IJMRD) www.ijmrd.info, Volume 01, Issue 01, Summer 2015 References Batten L, Baschieri A, Zulu E. Female and male migration patterns into the urban slums of Nairobi, 1996–2006: evidence of feminisation of migration? XXVI IUSSP International Population Conference; October 2009; Marrakech, Morocco. Baker J, Schuler N. Analyzing urban poverty: a summary of methods and approaches. World Bank Policy Research Paper 2004 (3399); 2004. Beguy D, Bocquier P, Zulu E. Circular migration patterns and determinants in Nairobi slum settlements. Demogr Res. 2010;23(20):549–586. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2010.23.20. Brockerhoff M, Brennan E. The poverty of cities in developing regions. Popul Dev Rev. 1998;24(1):75– 114. doi: 10.2307/2808123. Carael M, Ali M, Cleland J. Nuptuality and risk behaviour in Lusaka and Kampala. Afr J Reprod Health. 2001;5(1):83–89. doi: 10.2307/3583201 Chen N, Valente P, Zlotnik H. What do we know about recent trends in urbanization? In: Bilsborrow RE, editor. Migration, urbanization, and development: new directions and issues. Norwell: UNFPA–Kluwer Academic; 1998. pp. 59–88. Chepngeno G, Ezeh A. Between a rock and a hard place: perception of older people living in Nairobi City on return migration to rural areas. Glob Ageing Issues Action. 2007;4(3):67–78. Cardiovascular Diseases Risk Factors among the Urban Poor. APHRC Fact sheet. Nairobi, Kenya: African Population and Health Research Center; 2010. Cleland J, Bernstein S, Ezeh A, Faundes A, Glasier A, Innis J. Family planning: the unfinished agenda. Lancet. 2006;368(9549):1810–1827. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69480-4. Falkingham J. Measuring household welfare: problems and pitfalls with household surveys in central Asia. MOCT MOST Econ Policy Transitional Economies. 1999;9(4):379–393. doi: 10.1023/A:1009548324395. Fotso JC, Ezeh A, Madise N, Ziraba A, Ogollah R. What does access to maternal care mean among the urban poor? Factors associated with use of appropriate maternal health services in the slum settlements of Nairobi, Kenya. Matern Child Health J. 2009;13(1):130–137. doi: 10.1007/s10995-008-0326-4Government of Uttaranchal; 2003. Fotso JC, Ezeh A, Oronje R. Provision and use of maternal health services among urban poor women in Kenya: what do we know and what can we do? J Urban Health. 2008;85(3):428–442. doi: 10.1007/s11524-008-9263-1 Fotso JC. Urban-rural differentials in child malnutrition: trends and socioeconomic correlates in subSaharan Africa. Health Place. 2007;13(1):205–223. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2006.01.004. Kyobutungi C, Ziraba A, Ezeh AC, Yé Y. The burden of disease profile of residents of Nairobi’s slums: results from a demographic surveillance system. Popul Health Metr. 2008, 6: 1. SALIM NEEMA 117 International Journal of Migration Research and Development (IJMRD) www.ijmrd.info, Volume 01, Issue 01, Summer 2015 Madise NJ, Banda EM, Benaya KW. Infant mortality in Zambia: socioeconomic and demographic correlates. Biodemography Soc Biology. 2003;50(1 & 2):148–166. doi: 10.1080/19485565.2003.9989069 Zulu EM, Dodoo FN-A, Ezeh AC. Sexual risk-taking in the slums of Nairobi, Kenya, 1993–98. Popul Stud. 2002;56(3):311–323. doi: 10.1080/00324720215933 Madise NJ, Diamond ID. Determinants of infant mortality in Malawi: an analysis to control for death clustering within families. J Biosoc Sci. 1995;27(1):95–106. doi: 10.1017/S0021932000007033. Montgomery M, Gragnolati M, Burke K, Paredes E. Measuring living standards with proxy variables. Demography. 2000;37(2):155–174. doi: 10.2307/2648118. Mutua M, Kimani-Murage E. Childhood vaccination in informal urban settlements in Nairobi, Kenya: who gets vaccinated? BMC Public Health. 2011; 11(1): 6. Ndugwa RP, Zulu EM. Child morbidity and care-seeking in Nairobi slum settlements: the role of environmental and Socio-economic factors. J Child Health Care. 2008;12(4):314–328. doi: 10.1177/1367493508096206. Population and Health Dynamics in Nairobi’s Informal Settlements: Report of the Nairobi Crosssectional Slums Survey (NCSS) 2000. Nairobi, Kenya: African Population and Health Research Center; 2002. Report of the Nairobi Cross-sectional Slums Survey (NCSS) 2000. Nairobi, Kenya: African Population and Health Research Center; 2002. Second Report on Poverty in Kenya—Incidence and Depth of Poverty. Nairobi: Central Bureau of Statistics, Ministry of Planning and National Development; 2000. The state of African cities 2008—a framework for addressing urban challenges in Africa. Nairobi: UNHABITAT; 2008. Taffa N, Chepngeno G, Amuyunzu-Nyamongo M. Child morbidity and healthcare utilization in the slums of Nairobi, Kenya. J Trop Pediatr. 2005;51(5):279–284. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmi012, Taffa N, Chepngeno G. Determinants of health care seeking for childhood illnesses in Nairobi slums. Trop Med Int Health. 2005;10(3):240–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2004.01381.x. Taffa N, Sundby J, Bjune G. Reproductive health perceptions, beliefs and sexual risk-taking among youth in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Patient Educ Couns. 2003;49(2):165–169. doi: 10.1016/S0738-3991(02)00090-3. UN-Habitat. State of African cities 2010. Governance, Inequalities and Urban Land Markets. Nairobi, Kenya: UN-Habitat; 2010. World urbanization prospects: the 2009 revision. http://esa.un.org/unpd/wup/index.htm. Published 2009. Accessed April 08, 2011. SALIM NEEMA 118 International Journal of Migration Research and Development (IJMRD) www.ijmrd.info, Volume 01, Issue 01, Summer 2015 White R, Cleland J, Carael M. Links between premarital sexual behaviour and extramarital intercourse: a multi-site analysis. AIDS. 2000;14(15):2323–2331. doi: 10.1097/00002030-20001020000013. World Bank. Kenya poverty and inequality assessment. volume 1: synthesis report—draft report 2008. Washington, DC: 44190-KE. Zaba B, Pisani E, Slaymaker E, Boerma JT. Age at first sex: understanding recent trends in African demographic surveys. Sex Transm Infect. 2004;80(Suppl II):ii28–ii35. doi: 10.1136/sti.2004.012674. Ziraba AK, Mills S, Madise N, Saliku T, Fotso JC. The state of emergency obstetric care services in Nairobi informal settlements and environs: results from a maternity health facility survey. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9:46. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-9-46 Ziraba AK, Kyobutungi C, Zulu EM. Fatal injuries in the slums of Nairobi and their risk factors. J Urban Health. 2011. doi:10.1007/s11524-011-9580-7. Ziraba AK, Madise N, Mills S, Kyobutungi C, Ezeh A. Maternal mortality in the informal settlements of Nairobi city: what do we know? Reprod Health. 2009;6:6. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-6-6. Ziraba AK, Madise N, Mills S, Kyobutungi C, Ezeh A. Maternal mortality in the informal settlements of Nairobi city: what do we know? Reprod Health. 2009, 6: 6. Ziraba AK, Mills S, Madise J, Saliku T, Fotso JC. The state of emergency obstetric care services in Nairobi informal settlements and environs. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009; 9: 46. Zulu EM, Dodoo FN-A, Ezeh AC. Sexual risk-taking in the slums of Nairobi, Kenya, 1993– 98. Popul Stud. 2002;56(3):311–323. SALIM NEEMA 119

© Copyright 2026