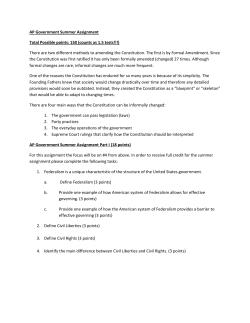

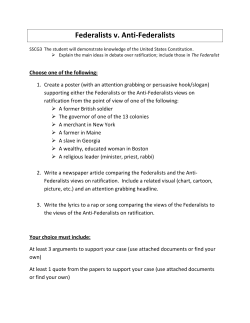

interim report