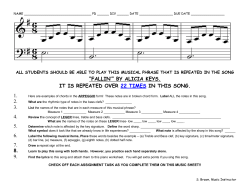

Feel Free to Forward this PdF to your interested Friends...