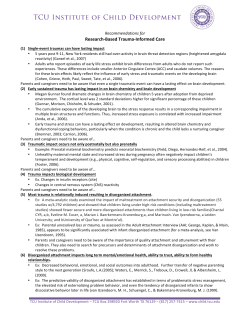

THE EXPERIENCE OF ANXIOUSLY ATTACHED HETEROSEXUAL ADULT PHENOMENOLOGICAL STUDY