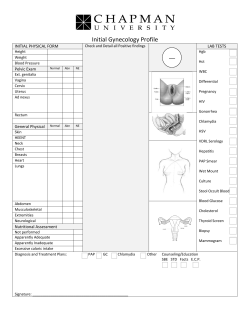

109 SIGN Chlamydia infection