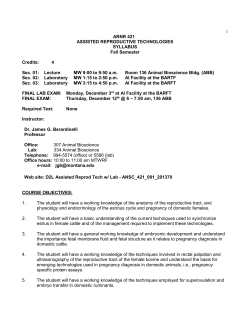

t