Methamphetamine Abuse

Methamphetamine Abuse

This course has been awarded

one (1.0) contact hour.

This course expires on January 24, 2015.

Copyright © 2006 by RN.com.

All Rights Reserved. Reproduction and distribution

of these materials are prohibited without the

express written authorization of RN.com.

First Published: January 10, 2006

Revised: January 10, 2009

Revised: January 24, 2012

Material protected by Copyright ©AMN Healthcare

Acknowledgements

RN.com acknowledges the valuable contributions of…

...Nadine Salmon, RN, BSN, IBCLC is the Clinical content Specialist for RN.com. Nadine earned her

BSN from the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa. She worked as a midwife

in Labor and Delivery, an RN in Postpartum units and Antenatal units, before moving to the United

Kingdom, where she worked as a Medical Surgical Nurse. After coming to the US in 1997, Nadine

worked in obstetrics and became a Board Certified Lactation Consultant. Nadine was the Clinical Pre

Placement Manager for the International Nurse Staffing division before joining RN.com. When not

writing courses and other educational materials, Nadine is currently pursuing her master’s degree in

Nursing Leadership.

…Susan Herzberger, RN, MSN, original course author.

Disclaimer

RN.com strives to keep its content fair and unbiased.

The author(s), planning committee, and reviewers have no conflicts of interest in relation to this

course. Conflict of Interest is defined as circumstances a conflict of interest that an individual may

have, which could possibly affect Education content about products or services of a commercial

interest with which he/she has a financial relationship.

There is no commercial support being used for this course. Participants are advised that the

accredited status of RN.com does not imply endorsement by the provider or ANCC of any commercial

products mentioned in this course.

There is no "off label" usage of drugs or products discussed in this course.

You may find that both generic and trade names are used in courses produced by RN.com. The use

of trade names does not indicate any preference of one trade named agent or company over another.

Trade names are provided to enhance recognition of agents described in the course.

Note: All dosages given are for adults unless otherwise stated. The information on medications

contained in this course is not meant to be prescriptive or all-encompassing. You are encouraged to

consult with physicians and pharmacists about all medication issues for your patients.

Purpose and Objectives

The purpose of Methamphetamine Abuse is to inform healthcare professionals about the acute and

chronic problems associated with methamphetamine abuse and to prepare them to intervene with

patients using methamphetamine.

After successful completion of this continuing education course, participants will be able to:

1. Describe the effects of methamphetamine.

2. Identify the populations most vulnerable to methamphetamine (meth) abuse.

3. List the hazards associated with clandestine meth labs.

4. Prepare a strategy to minimize the risk of meth-related violence.

5. Match interventions with meth-related medical emergencies.

6. State the prognosis for meth addicts in recovery.

Material protected by Copyright ©AMN Healthcare

Introduction

The expression “speed kills” comes from the 1960s and reflects the dangerous reputation of

methamphetamine at that time. Unfortunately, the majority of meth addicts did not live through that

time, so public awareness of the inherent dangers of this illicit drug requires persistent attention. In

this course, you will learn about the methamphetamine problem from several different perspectives.

You are likely to encounter patients with meth-related problems in all healthcare environments:

Emergency departments

Hospital wards

Primary care facilities

School health services

Pediatric clinics

Long-term facilities

Your “meth” patients may not be methamphetamine users, though. They may be first-responders to a

crisis, casualties of domestic exposure to meth, or meth laboratory clean-up crew members. Please

click on the glossary icon for a full list of slang words for methamphetamine.

Statistics

According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse [NIDA], (2011), approximately 13 million people 12

years and older have abused methamphetamine in their lifetimes. In 2010, approximately 353,000

were current users (NIDA, 2011).

A survey conducted in 2010 by the NIDA found that the abuse rate among 8th, 10th, and 12th

graders has declined significantly between 1999 and 2007, and remains unchanged since then.

Retrieved from NIDA, 2012

http://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/topics-in-brief/methamphetamine-addiction-progress-need-to-remain-vigilant

Abuse remains noteworthy in certain areas of the country with indicators suggesting particular

problems in Hawaii, the West Coast, and the Midwest.

After marijuana, methamphetamine and other amphetamine-type stimulants are the most widely used

Material protected by Copyright ©AMN Healthcare

illicit drugs worldwide (Urbina & Jones in Clark, 2008).

The potent addiction liability and destructive health and social consequences make the abuse

of methamphetamines particularly dangerous.

Methamphetamine Abuse

Methamphetamine is a psychostimulant used to treat attention-deficit disorder, narcolepsy, and

morbid obesity (Clark, 2008). It's also a Schedule II drug, meaning that it has a high potential for

abuse.

For many drug addicts, methamphetamine is the street drug of choice because it's less expensive

and has longer-lasting effects than crack cocaine (Clark, 2008). While cocaine is metabolized rapidly,

methamphetamine has a longer duration of action, producing extended euphoria.

Test Yourself:

Q: Substance abuse and __________ are strongly linked.

A: Mental Illness

Sources of Methamphetamine

Meth is easily available and affordable, compared to other illicit drugs. One hit of meth is about a

quarter of a gram and will cost a user about $25 (Frontline, 2012). However, the price of meth is

volatile, and depends on the drug's purity, the amount and where it is sold.

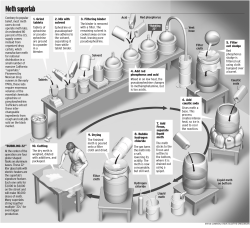

Illicit users of meth obtain the drug from imported sources or local clandestine labs. Local “mom &

pop” laboratories sprung up throughout the country when recipes for making meth out of OTC

ingredients became available over the Internet.

An epidemic began in the Midwest states and law enforcement systems became overburdened with

locating and seizing clandestine labs that increased tenfold in numbers over a decade (Markovich,

2005; ONDCP, 2004; NIDA, 2004b). People discovered that manufacturing meth is a lucrative

business that turns over a profit five to twenty times that of initial start-up costs. State legislative

efforts to control meth precursors such as pseudoephedrine and anhydrous ammonia are starting to

have a good effect now.

Law enforcers are now able to redirect their efforts to curb the Mexico-based drug trafficking

that provides the major supply of meth (ONDCP, 2005).

Test Yourself:

Q: Methamphetamine is manufactured using over the counter (OTC) medications such as:

A: A) Natamycin

B) Acetaminophen C) Pseudoephedrine D) Anhydrous chlorine

Material protected by Copyright ©AMN Healthcare

How Methamphetamine Is Used

Methamphetamine is a Schedule II narcotic that comes in 3 major forms:

Powder

Tablets

Chunks:Can be heated in a glass pipe and their fumes inhaled

Methamphetamine Powder.

Methamphetamine tablets.

Ice Meth chunks and pipe.

Images provided courtesy of the US DEA(Drug Enforcement Agency), 2012.

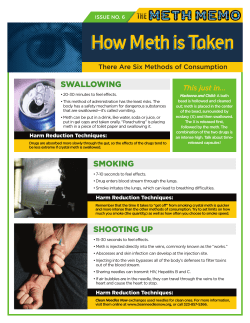

Meth can be smoked, snorted, injected, or ingested. Smoking is the most popular route among users

now (SAMHSA, 2005a).

Did You Know?

When methamphetamine is injected, the effects are usually felt within 3 to 5 minutes.

Action of Meth On The Brain

Methamphetamine acts by increasing the release of dopamine in the brain, which leads to feelings of

euphoria. However, this surge of pleasure is followed by a “crash” that often leads to repeated use of

the drug and eventually to difficulty feeling any pleasure at all, especially from natural rewards.

Long-term methamphetamine abuse also results in many damaging physical and psychiatric effects,

such as:

Addiction

Violent Behavior

Anxiety

Confusion

Insomnia

Psychotic symptoms (e.g. paranoia, hallucinations, delusions)

Cardiovascular problems (e.g. rapid heart rate, irregular heartbeat, increased blood pressure,

stroke)

(NIDA, 2012)

Patterns of Use

People take meth to feel euphoria and well-being, to increase their energy and stamina, to stay

awake, to be empowered, to lose weight, and to demonstrate assertiveness.

The onset of effect varies according to the route. The effects are felt within three to five minutes when

Material protected by Copyright ©AMN Healthcare

the meth is smoked, injected, or snorted. The effects from ingestion take 15 to 20 minutes. The

effects of meth last over twelve hours, compared to the effects of cocaine that last about half an hour.

Patterns of use among meth users vary widely. Some may use meth on occasion without becoming

dependent, and may still function normally within society. However, tolerance to meth builds quickly

and the extreme addictive potential of this drug makes almost all users vulnerable to its dangers.

Many meth users try to prevent a crash by taking just enough meth to stay functional. Others try to

recapture the initial euphoric rush they experienced the first time by bingeing on meth over several

days. The most intolerable time comes at the end of a binge, in a state called “tweaking.” Addicts feel

irritable, paranoid, and volatile (Markovich, 2005). This poses a danger for anyone attempting to

confront or curtail their actions.

Signs & Symptoms of Meth Abuse

These are some of the clinical signs and symptoms of methamphetamine abuse that you can assess:

Immediate Effects

↑ Heart rate and BP

↑ Body temperature

Hyper-vigilance

↑ Respirations

↓ Appetite

Poor impulse control

↑ Wakefulness

Tremors

Impaired judgment

↑ Physical activity

Egocentricity

Effects of Intoxication or Overdose

Dyspnea

Cardiac arrhythmias

Stroke

Tachycardia

Convulsions

Paranoia

Hyperthermia

Cardiovascular collapse

Aggressive behavior

Signs & Symptoms of Meth Intoxication

Since methamphetamines primarily affect the cardiovascular and central nervous

systems, the following signs and symptoms of meth intoxication can be observed below:

Insomnia

Tremors

Increased alertness

Loss of appetite

Hyperthermia

Increased body

movement / physical

Paranoia

Euphoria

activity

Tachycardia

Hallucinations

Restlessness

Hyperreflexia

(Clark 2008)

Presentation of a Meth High

Individuals who abuse methampetamines may not have outward physical signs, but those who do

can present with hypertension, tachycardia, tremors, and

Material protected by Copyright ©AMN Healthcare

weight loss (Gettig, Grady & Nowosadzka, 2006).

Individuals who chronically abuse meth usually have poor school and job performance, as well as

difficulties with interpersonal relationships.

Users may also experience:

Tremors

Agitation

Restlessness

Insomnia

Feelings of power, increased energy, aggression and alertness

(Gettig et al., 2006)

Excitement

Decreased appetite

Since methamphetamines have a very lengthy half-live, highs are generally intense and

lengthy (Gettig et al., 2006).

Presentation of a Meth Crash

Following a high, the user ultimately experiences an unpleasant "crash," which may last for a few

weeks (Gettig et al., 2006).

The withdrawal symptoms are essentially the opposite of what is experienced during the euphoric

stages of meth abuse.

Symptoms during the crash usually include:

Depression

Fatigue

Lack of energy

Hunger

Cravings for the drug

The combination of the high experience with the desire to avoid withdrawal

symptoms places addicts at risk for using the drug repeatedly, creating a vicious cycle of destruction

(Gettig et al., 2006).

Withdrawal Effects & Effects of Chronic Usage

Withdrawal Effects

Anxiety

Extreme frustration

Nightmares

Suicidal depression

Cognitive impairment

Insomnia followed by

hypersomnia

Agitated paranoia

Perceptual dullness

Dehydration + chills

Anhedonia (inability to

experience pleasure)

Fatigue

Effects of Chronic Usage

Weight loss

Rhabdomyolysis

Weakened immunity

Acute lead poisoning

Material protected by Copyright ©AMN Healthcare

Repetitive motor

activity

Violent speech and

behavior

Skin disorders + hair loss

Restlessness + irritability

Dental deterioration

Insomnia

Psychotic delusions

Long-Term Effects of Meth Abuse

As addiction to methamphetamine worsens, users develop tolerance to the drug. To achieve the

desired "high," depending on their personal sensitivity, they may need to increase the amount of meth

used or change the route of administration, and often embark on a "binge and crash" cycle (Gettig et

al., 2006). The lack of sleep and nourishment that accompanies such episodes can lead to paranoia,

psychosis, and unpredictable, violent, or risk-taking behavior.

Chronic meth abuse can also permanently alter brain chemistry, with resultant developement of

chronic psychiatric illnesses such as depression and schizophrenia is increased (Gettig et al., 2006).

Long-term abusers of meth may also develop insomnia and movement disorders Gulien, in Gettig et

al., 2006).

The most common complication of meth abuse is addiction, which has grave emotional, physical, and

financial complications (Hardman &t Limbird, in Gettig et al., 2006).

Methamphetamine-induced paranoia and hallucinations can lead to rage, domestic violence,

child abuse, murder, and suicide.

Neurological Damage

Methamphetamine targets the central nervous system (CNS) by stimulating the

release of dopamine and, in lesser amounts, norepinephrine and serotonin, and inhibits their reuptake

(Clark, 2008).

Dopamine is a neurotransmitter that causes CNS excitation. It elevates mood, creates feelings of

euphoria, and enhances body movement and reflexes. However, high doses of methamphetamine

damage nerve terminals in areas of the brain (Clark, 2008).

Life-threatening medical complications can occur with a dose of any size. Tachycardia, hypertension,

and increased metabolism commonly occur, but more serious effects, such as hyperthermia,

seizures, MI, stroke, and even death, are possible (Clark, 2008).

Brain abnormalities will show up on MRIs and PET scans that resemble those seen in dementia and

schizophrenia (Thompson, 2004).

Did You Know?

Even with meth abstinence, only partial reversal of the neurotoxic damage is expected, although

some symptoms may slowly resolve as the brain adapts and compensates for permanent deficits

(Wang, et al., 2004).

Material protected by Copyright ©AMN Healthcare

Changes In Body Image

Chronic methamphetamine abuse can have devastating physical as well as psychosocial

consequences.

Changes in body image occur not only from malnutrition and poor hygiene, but also from selfdestructive urges to purge the body of imagined "meth bugs". Methampphetamine abusers develop a

crawling sensation on their skin, as if a bug is tunneling under the skin. In response to this sensation,

user pick incessantly at the skin, causing skin wounds, infections, scabs, and scars (Clark, 2008).

Even though users may be aware that there is nothing on the skin, they will continue to scratch and

pick at the skin, and sometimes use needles, glass, or other sharp objects to "dig out," or get rid of,

the sensation (Clark, 2008). This practice may reduce the distress, but puts the user at risk for

disease, infection, and altered body image.

Chronic methamphetamine use also damages the teeth and gums, resulting in a condition commonly

referred to as "meth mouth." This is often caused by dental caries and periodontal disease that occur

as a result of poor oral hygiene, poor nutrition and xerostomia (dry mouth), caused by chronic

exposure to the chemicals that make up methamphetamines (Clark, 2008).

Meth abusers are also at increased risk for blast-related trauma, chemical and thermal burns, and

inhalation injury from exposure to the chemicals used in meth labs (Clark, 2008).

Image of a person with dermatillomania (also known as

pathologic skin picking), that results in skin sores due to

self-inflicted skin picking on arms, shoulders and chest.

Image provided by Wikipedia (2012) in the Public Domain.

This is a case of suspected meth mouth with a close-up

shot of the lower right posterior teeth. This patient was

treated at the University of Tennessee Health Science

Center: College of Dentistry in Memphis, TN. Image

provided by GNU Free Documentation License, 2012.

Intoxication & Overdose

Emergency department care for meth intoxication focuses on managing life-threatening

symptoms and/or psychotic behavior.

There is no antidote available for methamphetamine intoxication.

Supportive measures include:

Treat hyperthermia with cooling measures, such as an ice bath.

Take standard measures to control convulsions and cardiovascular events. Benzodiazepines

are sometimes used for extreme anxiety.

Short- term neuroleptics (anti-psychotics) and admission to a psychiatric department may be

needed for toxic psychosis.

Material protected by Copyright ©AMN Healthcare

This individual has the potential to become violent; do you observe any

potential weapons?

Yes. Her cell phone and the chair.

Management For Potential For Violence

The potential for violence to erupt in a meth-intoxicated, binging, or tweaking patient is something to

think about before you are in the midst of danger.

These are some ways to lower your risk of harm (DHHS, 2011):

Orient the patient by identifying yourself and your purpose

Call the patient by name

Take the patient to a quiet, spacious place with minimal stimuli

Remain non-confrontational

Acknowledge the patient’s agitation and distress

Remove potential weapons

Have a back-up plan for a team approach to managing any violence that may occur, if

necessary

Toxic Exposures

People exposed to toxic chemicals from a clandestine meth lab have symptoms of respiratory and

eye irritation, headache, dizziness, nausea and vomiting, and shortness of breath (ONDCP, 2005;

Markovich, 2005). A variety of chemicals may be used in the manufacturing of meth, including

corrosives, solvents, and respiratory irritants (Colorado Drug Endangered Children Organization,

2005). Ammonia or hydrogen chloride is a standard ingredient that presents a significant danger and

risk of fatality.

Possible damaging effects of ammonia & hydrogen chloride:

(Source: Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, 2004)

Material protected by Copyright ©AMN Healthcare

There is no antidote for these chemical exposures. Inducing emesis is not advised if the chemicals

have been ingested, but diluting stomach contents with water or milk may be helpful.

Once the patients have been decontaminated with a total body and hair washing and the eyes

irrigated, treatment is supporting of basic respiratory and cardiovascular functions.

Thermal Burns

The chemicals used to make meth are highly volatile, and patients arriving from a meth lab may also

have thermal burns from an explosion.

Whether the burns are caused by flames or chemicals or a combination of these, you will need to

evaluate what percentage of the body is burned and identify the depth or degree of the burns.

Document your findings on a body map. If over 30% of the total body surface area is burned, expect a

systemic inflammatory response.

Test Yourself:

Q: If over _____ of the total body surface area is burned, expect a systemic inflammatory response.

A: 30%

Children Removed From Meth Lab Sites

Adults without symptoms who are involved in a meth lab seizure will not show up for medical care but

all children removed from the situation will require a complete medical evaluation within 24 hours

(CDEC, 2005). Children are at greater risk for toxicity than adults because of a proportionately larger

lung surface area and closer proximity to the ground where vapors tend to collect (ATSDR, 2004).

You might think that a pungent, disagreeable odor would naturally keep children from wandering into

a dangerous environment, but olfactory fatigue occurs when the chemical exposure is prolonged,

dismantling the natural protective sense.

Evaluate children for effects of recent chemical exposure as well as for CNS depression due to

chronic exposure to chemicals. Some may have a strong odor resembling cat urine, associated with

meth production (Markovich, 2005). Note any signs and symptoms of child abuse, such as

emaciation, lack of grooming and hygiene, noticeable fatigue, bruises or injuries, and odd behavior.

Some studies show that over half of the children removed from meth labs test positive for meth

(CDEC, 2005). In some states you will be asked to collect a urine drug specimen for the purpose of

assisting with prosecution.

Treatment

Currently, the most effective treatments for methamphetamine addiction are comprehensive

cognitive-behavioral interventions. An example of such an intervention is the use of the Matrix Model,

which is a behavioral treatment approach that combines behavioral therapy, family education,

individual counseling, 12-step support, drug testing, and encouragement for non drug-related

activities.

Contingency management interventions, which provide tangible incentives in exchange for engaging

in treatment and maintaining abstinence, have also been shown to be effective (NIDA, 2010).

Material protected by Copyright ©AMN Healthcare

There are no medications at this time approved to treat methamphetamine addiction; however, this is

an active area of research for NIDA (NIDA, 2010).

The combination of predictable relapses and harsh setbacks in achieving treatment goals

explains the resistance meth addicts have to entering treatment.

Prevention & Screening

Some ways you can work preventatively to reduce the methamphetamine problem are:

Routinely screening your patients for substance use

Enhancing your awareness of vulnerable populations

Educating patients and the public about meth

Supporting those legislative efforts proven to work

Screening for substance abuse should be as routine as asking about prescription medications. It can

be as direct and simple as an adapted version of the CAGE questionnaire (See Appendix One):

Have you ever felt the need to cut down on your alcohol or drug habits?

Are you annoyed by criticism from others over these habits?

Have you ever felt bad about this issue?

Have you ever had to have an alcohol or drug fix in the morning?

Prevention & Screening

Screening for substance use should not be done when patients are obviously under the influence of

alcohol or drugs. If the patient is “under the influence” expect poly-drug use, asking about specific

daily amounts being used and the last time they were used.

Using street terms and expressing a nonjudgmental attitude may increase the patient’s willingness to

disclose information. Tests for screening of specific substances may be useful for planning treatment

but if blood alcohol levels and urine drug screens are done, obtain the patient consent first (National

Guidelines Clearinghouse, 2005).

Vulnerable People

People who fall into a high-risk category for meth abuse are identified by demographic statistics and

constitutional vulnerability. Demographic groups at risk are:

Young adults between 20 and 30

People whose occupations require physical stamina

People trying to lose weight

People wanting to enhance their physical, mental, or sexual performance

Those with a constitutional vulnerability suffer from chronic depression, low energy, and low

self-esteem. For them, the first experience of what they consider well-being may have come with their

first use of meth. They cannot recapture that experience because repeated usage is less and less

satisfying, but the addiction to trying is extremely powerful.

Material protected by Copyright ©AMN Healthcare

Test Yourself:

Q: People who fall into a high-risk category for meth abuse are sometimes identified by:

A: A) Class B) Income C) Ethnicity D) Demographic statistics

Patient Education

Your efforts to teach patients and the public about meth can make a measurable difference. Since

1999, public education campaigns actively confronting the meth problem have produced a decline in

meth use among youth (University of Michigan, 2004).

Parents today tend to underestimate the presence and influence of drugs in their adolescents’ lives

though (Partnership for a Drug-Free America, 2005). This points to a need for more parental

education.

Research shows that decreasing usage of a particular drug is directly connected to how widely that

drug is perceived to be dangerous (NIDA, 2004a). Research also shows that public memory of a

drug’s dangers fades over the decades. As a nurse, you can be alert to the public’s need for

information.

Test Yourself:

Q:What are the warning signs of a Clandestine Meth Lab?

A: A strong, pungent odor of solvents, ammonia, or ether; a residence with blacked-out windows; a lot

of night activity; excessive trash (Source: Division of Narcotics Enforcement, Iowa Department of

Public Safety, 2005.)

Conclusion

Among the many illicit drugs in circulation, methamphetamine is especially threatening to health. This

is because of meth’s powerful addictive potential and the extreme neurological consequences.

Meth addiction not only blocks enjoyment of life but tragically steals years of normal productivity from

many people in their first decade of adulthood.

Having studied the problem, you will be ready to intervene against these odds as you work with

patients who have abused methamphetamines.

Appendix One: The CAGE Questionnaire

The CAGE questionnaire, the name of which is an acronym of its four questions, is a widely used

method of screening for alcoholism.

It is not valid for diagnosis of other substance use disorders, although somewhat modified versions of

the CAGE are frequently implemented for such a purpose.

Two or more “yes” responses indicate that further evaluation is needed.

Material protected by Copyright ©AMN Healthcare

Scoring: Responses on the CAGE are scored 0 for "no" and 1 for "yes," with a higher score an

indication of alcohol problems. A total score of 2 or greater is considered clinically significant.

Source: Ewing, J. A. (1984). Detecting alcoholism: The CAGE Questionnaire. Journal of the American Medical Association, 252,

1905–1907.

Glossary of Terms

Bathtub crank: poor quality methamphetamine; methamphetamine produced in bathtubs

Beannies: methamphetamine

Bikers coffee: methamphetamine and coffee

Black beauty: methamphetamine

Blade: crystal methamphetamine

Blue devils: methamphetamine

Box labs: small, mobile, clandestine labs used to produce methamphetamine

Brown: marijuana; heroin; methamphetamine

Chalk: Crack Cocaine; amphetamine; methamphetamine

Christmas tree meth: green methamphetamine produced using Drano crystals

Chrome: crystal methamphetamine

Cinnamon: methamphetamine

Cook: drug manufacturer; mix heroin with water; heating heroin to prepare it for injection

Cooker: to inject a drug; person who manufactures methamphetamine

CR: methamphetamine

Crank: Crack Cocaine; heroin; amphetamine; methamphetamine; methcathinone

Crankster: someone who uses or manufactures methamphetamine

Crink: Methamphetamine

Cristina (Spanish): methamphetamine

Material protected by Copyright ©AMN Healthcare

Croak: crack mixed with methamphetamine; methamphetamine

Crossles: methamphetamine

Crush and rush: method of methamphetamine production in which starch is not filtered out of the ephedrine

or pseudoephedrine tablets.

Crypto: methamphetamine

Crystal glass: crystal shards of methamphetamine

Crystal meth: methamphetamine

Crystal: Cocaine; amphetamine; methamphetamine; PCP

Desogtion: methamphetamine

Dropping: wrapping methamphetamine in bread and then consuming it

Elbows: one pound of methamphetamine

Fast: methamphetamine

Fire: Crack and methamphetamine; to inject a drug

Five-way: combines snorting of heroin, cocaine, methamphetamine, ground up flunitrazepam pills, and

drinking alcohol

Geep: methamphetamine

Geeter: methamphetamine

Getgo: methamphetamine

Getting glassed: to snort methamphetamine

Glass: heroin; amphetamine; hypodermic needle; methamphetamine

Go-fast: methcathinone; crank; methamphetamine

Half elbows: pound of methamphetamine

Hiropon: smokable methamphetamine

Holiday meth: green methamphetamine produced using Drano crystals

Hot Ice: smokable methamphetamine

Hot rolling: liquefying methamphetamine in an eye dropper and then inhaling it

Hotrailing: to heat methamphetamine and inhale the vapor through nose using a plastic tube

Hugs and Kisses: combination of methamphetamine and methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA)

Ice: cocaine; crack cocaine; smokable methamphetamine; methamphetamine;

methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA); phencyclidine (PCP)

Jet fuel: PCP; methamphetamine; methamphetamine combined with PCP (phencyclidine)

L.A. glass: smokable methamphetamine

L.A. ice: smokable methamphetamine

Lemon drop: methamphetamine with a dull yellow tint

Load of Laundry: Methamphetamine

Maui-wowie: marijuana; methamphetamine

Meth head: methamphetamine regular user

Meth monster: one who has a violent reaction to methamphetamine

Meth speed ball: methamphetamine combined with heroin

Meth: Methamphetamine

Mexican crack: methamphetamine with the appearance of crack; methamphetamine

Mexican speedballs: crack and methamphetamine

Nazimeth: methamphetamine

OZs: methamphetamine

P and P: methamphetamine used in combination with MDMA (methylenedioxymethamphetamine) and Viagra

Material protected by Copyright ©AMN Healthcare

Paper: a dosage unit of heroin; one-tenth of a gram or less of the drug ice or methamphetamine

Party and play: methamphetamine used in combination with MDMA (methylenedioxymethamphetamine) and

Viagra

Pink elephants: methamphetamine

Pink hearts: amphetamine; methamphetamine

Pink: methamphetamine

Po coke: methamphetamine

Poor man's coke: methamphetamine

Quill: cocaine; heroin; methamphetamine

Red: under the influence of drugs; methamphetamine

Redneck cocaine: methamphetamine

Rock: methamphetamine

Shabu: combination of powder cocaine and methamphetamine; crack cocaine; methamphetamine;

methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA)

Sketch: methamphetamine

Soap dope: methamphetamine with a pinkish tint

Spackle: methamphetamine

Sparkle: methamphetamine that has a somewhat shiny appearance

Speed freak: habitual user of methamphetamine

Speed: Crack Cocaine; amphetamine; methamphetamine

Speedballing: to shoot up or smoke a mixture of cocaine and heroin; ecstasy mixed with ketamine; the

simultaneous use of a stimulant with a depressant

Spoosh: methamphetamine

Stove top: crystal methamphetamine; methamphetamine

Super ice: smokable methamphetamine

The five way: heroin plus cocaine plus methamphetamine plus Rohypnol (flunitrazepam) plus alcohol

Tic: PCP in powder form; methamphetamine

Tina: methamphetamine; crystal methamphetamine; methamphetamine used with Viagra

Trash: methamphetamine

Tweek: methamphetamine-like substance

Twisters: Crack and methamphetamine

Wash: methamphetamine

Water: blunts; methamphetamine; PCP; a mixture of marijuana and other substances within a cigar; Gamma

hydroxybutyrate (GHB)

Wet: blunts mixed with marijuana and PCP; methamphetamine; marijuana cigarettes soaked in PCP

("embalming fluid") and dried

White Cross: amphetamine; methamphetamine

Working man's cocaine: methamphetamine

Ya Ba: a pure and powerful form of methamphetamine from Thailand; "crazy drug"

Yellow bam: methamphetamine

Yellow jackets: depressants; methamphetamine

References

Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR). (2004). Medical management guidelines. Retrieved

10/08/05, from http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/

Material protected by Copyright ©AMN Healthcare

Clark, J. (2008). The Danger Next Door: Methamphetamine. RN Web.com.

Colorado Drug Endangered Children (CDEC) Organization (2005). Clandestine methamphetamine labs frequently asked

questions. Retrieved 10/08/05, from http://www.colodec.org.

Department of Health & Human Services (DHHS), (2011). Treatment of stimulant use disorders. Quick guide for clinicians.

Based on TIP 33. Publication SMA 01-3598.

Division of Narcotics Enforcement. Iowa Department of Public Safety. (2005). Clandestine laboratories. Retrieved

10/06/05, from http://www.dps.state.ia.us/DNE/clanlab.shtml

Frontline (2012). The Meth Epidemic: Frequently Asked Questions. Retrieved January 4, 2012

from:http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/meth/faqs/#12

Gettig, J., Grady, S. & Nowasadzka, I. (2006). Methamphetamines: Putting The Brakes On Speed. The Journal of School

Nursing, 22(2), p. 66-73.

Herzberger, S. (2005). Meth addiction. Advance for Nurses. Retrieved 10/05/05, from http://www.advanceweb.com.

Markovich, K. (2005). Methamphetamine abuse. Advance for Nurse Practitioners. Retrieved 4/03/05, from

http://nurse-practitioners.advanceweb.com.

National Guidelines Clearinghouse. (2005). Screening and ongoing assessment for substance use. Retrieved 10/06/05,

from http://www.hivguidelines.org.

National Institute on Drug Abuse [NIDA], 2010. Info Facts: Methamphetamine Abuse.Retrieved January 4, 2012 from:

http://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/infofacts/methamphetamine

NIDA. (2004a). Monitoring the Future: National results on adolescent drug use. Retrieved 7/12/05, from

http://www.monitoringthefuture.org.

NIDA. (2004b). NIDA InfoFacts: Methamphetamine. Retrieved 7/23/05, from http://www.nida.nih.gov.

Partnership for a Drug-Free America. (2005). Partnership Attitude Tracking Study 2004. Retrieved 7/12/05, from

http://www.drugfree.org.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], (2005a). Smoked

methamphetamine/amphetamines: 1992-2002. The DASIS Report, January 7. 2005.

SAMHSA. (2005b). Youth drug use continues to decline. Retrieved 9/14/05, from http://www.samhsa.gov.

Thompson, P. (2004). Structural abnormalities in the brains of human subjects who use methamphetamine. The Journal

of Neuroscience, 24(26): 6028-6036.

United States Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), 2012. Methamphetamine Images. Retrieved January 4, 2012

from: http://www.justice.gov/dea/images_methamphetamine.html

University of Michigan. (2004). Overall teen drug use continues gradual decline; but use of inhalants rises. Retrieved

7/12/05, from http://www.monitoringthefuture.org.

Wang, G. et al. (2004). Partial recovery of brain metabolism in methamphetamine abusers after protracted abstinence.

American Journal of Psychiatry, 161(2): 242-248.

At the time this course was constructed all URL's in the reference list were current and accessible. RN.com is

committed to providing healthcare professionals with the most up to date information available.

© Copyright 2006, AMN Healthcare, Inc.

Please Read:

This publication is intended solely for the use of healthcare professionals taking this course, for credit, from RN.com. It is

Material protected by Copyright ©AMN Healthcare

designed to assist healthcare professionals, including nurses, in addressing many issues associated with healthcare. The

guidance provided in this publication is general in nature, and is not designed to address any specific situation. This

publication in no way absolves facilities of their responsibility for the appropriate orientation of healthcare professionals.

Hospitals or other organizations using this publication as a part of their own orientation processes should review the

contents of this publication to ensure accuracy and compliance before using this publication. Hospitals and facilities that

use this publication agree to defend and indemnify, and shall hold RN.com, including its parent(s), subsidiaries, affiliates,

officers/directors, and employees from liability resulting from the use of this publication. The contents of this publication

may not be reproduced without written permission from RN.com.

Material protected by Copyright ©AMN Healthcare

© Copyright 2026