Hemophagoctic Lymphohistiocytosis – Recent Concept Maitreyee Bhattacharyya*, MK Ghosh** Abstract

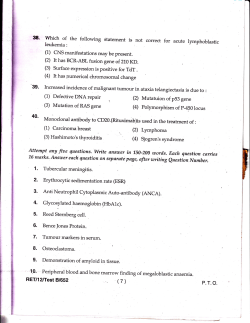

Review Article Hemophagoctic Lymphohistiocytosis – Recent Concept Maitreyee Bhattacharyya*, MK Ghosh** Abstract Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis is a rare condition characterized by highly stimulated but inactive immune response. The disease may be inherited or acquired due to infections, collagen vascular diseases and malignancies. The pathological hallmark of the syndrome is aggressive proliferation of macrophages and histiocytes. Decreased NK cell activity results in increased T cell activation resulting production of large quantities of interferon γ (IFNγ), tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) and granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF). This causes sustained macrophage activation and tissue infiltration as well as production of interleukin 1 (IL1) and interleukin 6 (IL6).The resulting inflammatory reaction causes extensive damage and associated symptoms. Patients with HLH commonly present with high fever, anemia and splenomegaly. Minimal diagnostic parameters are a complete hemogram, liver function test, serum triglycerides and ferritin, coagulation profile including fibrinogen and bone marrow aspiration. Two highly sensitive diagnostic marker are an increased plasma concentration of the α chain of soluble IL2 receptor (CD25) and impaired NK cell activity. Hyperinflammation can be treated with steroid, Cyclosporine prevents T lymphocytes and immunoglobulin infusion helps to control the infection. Etoposide may be life saving specially in case of HLH with Ebstein Barr Viruses infection. The Histiocyte Society in 1994 developed a common treatment protocol (HLH-94). In January 2004 a revised HLH treatment protocol was opened entitled HLH-2004, which is based on HLH-94 with minor modifications. There is a high remission rate on the HLH-94 and HLH-2004 treatment protocols. © H INTRODUCTION - emophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH ) is a rare but potentially life threatening condition characterized by uncontrolled activation of macrophages and lymphocytes. Pediatric age group is most commonly affected but it can occur at any age. It is not a single disease and can be encountered in association with a variety of underlying diseases that leads to highly stimulated but inactive immune response. Classification : 1. Inherited HLH Familial HLH (Farquhar disease) - Known genetic defects (perforin, munc 13-4, syntaxin 11) - Unknown genetic defects. Immune deficiency syndrome - Chediak Higashi syndrome - Griscelli syndrome - X- linked lymphoproliferative syndrome 2. Acquired HLH Exogenous agents (infectious organisms, toxins) *Associate Professor, **Professor and Head, Department of Hematology, N.R.S. Medical College, Kolkata, India. © JAPI • VOL. 56 • JUNE 2008 Infection – associated hemophagocytic syndrome (IAHS) Endogenous products (tissue damage, metabolic products) - Rheumatic diseases - Macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) Malignant disease The syndrome, which has also been referred to as histiocytic medullary reticulosis, was first described in 1939.1 HLH was initially thought to be a sporadic disease caused by neoplastic proliferation of histiocytes. Subsequently, a familial form of the disease2 (now referred to as familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (FHLH)3 was described. Familial HLH is an inherited autosomal recessive disorder first described by Farquhar and Claireaux in 1952,2 estimated to occur in a frequency of 1 in 50,000 births. The diagnosis of FHLH is made based on the presence of clinical criteria and is confirmed by molecular genetic testing. Four disease subtypes (FHL1, FHL2, FHL3, and FHL4) are described; three genes have been identified and characterized: PRF1 (FHL2), UNC13D (FHL3), and STX11 (FHL4). Molecular genetic testing of the PRF1 (FHL2), UNC13D (FHL3), and STX11 (FHL4) genes is available on a clinical basis (Table 1). Secondary HLH (ie acquired HLH) occurs after www.japi.org 453 strong immunologic activation such as that occur with a variety of viral, bacterial, fungal, and parasitic infections, as well as collagen-vascular diseases10-13 and malignancies, particularly T-cell lymphomas.14-17 The association between HLH and infection is important because 1) both sporadic and familial cases of HLH are often precipitated by acute infections; 2) HLH may mimic infectious illnesses, such as overwhelming bacterial sepsis and leptospirosis;18 3) HLH may obscure the diagnosis of a precipitating, treatable infectious illness (as reported for visceral leishmaniasis;19 and 4) a better understanding of the pathophysiology of HLH may clarify the interactions between the immune system and infections The clinical picture of HLH can be induced by a variety of infectious organisms. The patient in the original report by Risdull and colleagues were mostly associated with viral infection following organ transplantation.20 Subsequently it was clear that it may be associated with viruses as well as a no of bacteria, fungi, mycobacteria and parasite and the term Viral Associated Hemophagocytic Syndrome (VAHS) was redesigned as Infection Associated Hemophagocytic Syndrome (IAHS). A review of published cases in children diagnosed with IAHS before 1996 reported that more than half of them were from Far East. Ebstein Barr Virus (EBV) was the triggering virus in 74% of the children in whom an infectious agent could be identified.21 Fardet et al reported Human Herpesvirus 8 associated HLH in Human immunodeficiency virus infected patients.22 HLH in association with malignant disease is well known entity in adults but rare in children. Most common malignancy associated with HLH is Lymphoma. In a recent review of patient with lymphoma associated hemophagocytic syndrome (LAHS) from Japan EBV genome was detected from more than 80% of T/NK cell lymphoma but rarely from B cell lymphoma.23 HLH has also been described in association with inborn error of metabolism like Lysinuric Protein Intolerence (LPI).24 Pathophysiology The pathological hallmark of the syndrome is aggressive proliferation of macrophages and histiocytes which phagocytose other blood cells leading to the clinical symptoms. This uncontrolled growth is nonmalignant and does not appear clonal in contrast to the lineage of cells in Langerhans cells histiocytosis. The spleen, lymph nodes, bone marrow, liver, skin and membranes that surrounds the spinal cord are preferential site of involvement.25 Over the past 2 decades, the underlying pathophysiology of HLH has been characterized, although the processes are not entirely understood. A current accepted theory involves an inappropriate immune reaction caused by activated T cells associated with macrophage activation and inadequate apoptosis of immunogenic cells.26 Although the precise mechanism is unclear many research team propose convincing pictures for the role of perforin or NK cells in the HLH subtypes.2729 NK and cytotoxic T cells kill their targets through cytolytic granules containing perforins and granzyme. When activated by challenges NK cells release granules containing granzymes and perforins which forms pores in the target cell membrane and causes osmotic lysis and protein degradation respectively. Patients with HLH have severe impairment of the cytotoxic function of NK cells and cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Decreased NK cell activity results in increased T cell activation and expansion with resulting production of large quantities of cytokines, including interferon γ (IFNγ), tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) and granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF). This causes sustained macrophage activation and tissue infiltration as well as production of interleukine1 (IL1) and interleukine 6 (IL6). The resulting inflammatory reaction causes extensive damage and associated symptoms30 (Fig. 1). Inflammatory cytokines are responsible for the characteristic disease markers such as cytopenias, coagulopathy and high triglycerides. Upon contact between the effector killer cell and the target cell, an immunological synapses is formed and cytolytic granules have to traffic the contact site, dock and fuse with the plasma membrane and release their content. All known defects in HLH seems to be involved in this processes. LYST mutations impair granule secretion, RAB 27α deficiency leads to impaired docking at the membrane, mutations in UNC13 causes defective granule priming at the immunologic synapses. Finally lack of PRF1 leads to loss of cytolytic activity. In XLP, granule mediated cytotoxicity is defective through impaired lymphocyte activation. Factors leading to cytolytic defects in acquired HLH is less clear. Viruses may interfere with T cell activity Table 1 : Locus name and genes associated with familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis Locus Name % of FHLH FHL1 4 inbred Pakistani Families4 FHL2 20-30% worldwide, 50% in African American families5-7 FHL3 20-30% world wide6,8 FHL4 ~ 20% of Turkish/Kurdish families8,9 454 Mutations Chromosomal Locus N/A 9q21.3-q22 >50 distinctive mutations throughout 10q22 the entire coding region >10 mutations throughout the entire 17q25.1 coding region and splicing sites 3 recurrent mutations 6q24 www.japi.org Protein name Unknown Perforin-1 Unc-13 homolog D Syntaxin-11 © JAPI • VOL. 56 • JUNE 2008 Table 2 : Clinical signs and laboratory abnormalities associated with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis Clinical sign Fever* Splenomegaly* Hepatomegaly Lymphadenopathy Rash Neurologic signs Laboratory abnormality Anemia* Thrombocytopenia* Neutropenia* Hypertriglyceridemia* Hypofibrinogenemia* Hyperbilirubinemia Fig. 1 : Schematic representation of possible immunopathologic mechanisms in infection-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH). TNF-α = tumor necrosis factor-α ; IFN-γ = interferon-gamma; IL-1 = interleukin-1; IL-2 = interleukin-2; IL-6 = interleukin-6; IL-18 = interleukin-18; sFasL = soluble Fas ligand; T = T-lymphocyte; M = macrophage; EBV = Epstein-Barr virus. Fig. 2 : Overview of the treatment protocol HLH-94. Dexa = dexamethasone daily [pulses are 10 mg/m2 for 3 days]; VP16 = etoposide 150 mg/m2 intravenously; CSA = cyclosporin A; I.T. therapy = intrathecal methotrexate [if progressive neurological symptoms or if an abnormal CSF has not improved].) by specific proteins or cytokines.31,32 Macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) occurs in children and adults with autoimmune diseases most commonly seen in association with systemic onset juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (sJRA) or adult onset Still,s disease but also occur rarely with systemic lupus erythematosus or other entities. 33,34 Clinical picture and laboratory findings are similar to HLH. Patients of sJRA was found to have low NK cell function and perforin expression compared to other form of rheumatoid arthritis.35 MAS is a grave disorder with a mortality of about 10-20%. It has been suggested by some rheumatologists that MAS be classified as a form of secondary HLH.36,37 Clinical Features Patients with HLH commonly present with high fever, anemia and splenomegaly. The fever often fluctuates with complete remission and recurrences. Severe fulminant liver failure with coagulopathy or neurological symptoms may dominate the clinical © JAPI • VOL. 56 • JUNE 2008 % of patients affected 60-100 35-100 39-97 17-52 3-65 7-47 % of patients affected 89-100 82-100 58-87 59-100 19-85 74 Reference 3,46 3, 46 3,46 3,46 3,46 3,46 Reference 3,44,45 3,44, 45 3,44,46 3,44,46 3,44,46 44 * Proposed diagnostic criterion for HLH2 picture and thereby delay the diagnosis of HLH. Nearly 75% of patients will show some form of CNS involvement – including seizures, ataxia, hemiplegia, altered sensorium. Patient may have even only neurological manifestations.38,39 About 65% of patients will have skin rashes40 (Table 2). The diagnostic criteria set forth by the Histiocytic Society for inclusion in the international registry41 for HLH is as follow – I) Fever as high as 38.5°C for 7 days or more. II) Splenomegaly – 3 cm below left costal margin III) Cytopenias – - Absolute Neutrophils < 1000/µL - Platelets less than100,000/µL - Hemoglobin < 9 g/dL IV) Fibrinogen < 1.5 g/L or fasting triglyceride >3 mmol/L V) Hemophagocytosis in spleen, lymph node or Bone Marrow. VI) Serum Ferritin > 500 µg/L VII) sCD25 > 2400 U/L VIII)Decreased or altered NK cell activity. Laboratory investigations In every patient with prolonged fever, hepatosplenomegaly and pancytopenia, the diagnosis of HLH should be considered. Minimal diagnostic parameters are a complete hemogram, liver function test, serum triglycerides and ferritin, coagulation profile including fibrinogen. Ferritin has been observed as a marker of HLH with the serum level paralleling the course of the disease.26 Altered hepatic function including hyperbilirubinemia, increased hepatic enzymes and low albumin has also been reported.42 All patients should undergo bone marrow aspiration, however, hemophagocytosis may not be present in the initial bone marrow smears, only increased monocytes and monohistiocytic cells may be present. In about 50% patients there may be elevated cell count, protein or both in the CSF even in the absence of clinical www.japi.org 455 features. Two highly sensitive diagnostic marker are an increased plasma concentration of the α chain of soluble IL2 receptor (CD25) and impaired NK cell activity.43 In October 2002, the Arico group proposed an approach to the diagnostic work up of a patient with suspected HLH. The laboratory work-up should involve perforin expression by NK cell by using flow cytometry. Patients lacking perforin expression should be analyzed for the PRFI gene mutation, NK cell activity helps to differentiate between reactive form of HLH from familial type. Normal activity is suggestive of the reactive form rather than familial type. 25 Search for a triggering infectious agent is important, however it should be emphasized that with the possible exception of leishmaniasis, anti-infectious therapy alone is not sufficient to control HLH (Table 2). Therapy The aim of treatment of HLH is to suppress the severe hyperinflammation and also to control the infection which has triggered the syndrome. In familial HLH the ultimate aim should be stem cell transplantation to replace the defective immune system with normal functioning immune system. Hyperinflammation can be treated with steroid, which is cytotoxic for lymphocytes and inhibit secretion of various cytokines. Dexamethasone is the drug of choice since its CSF penetration is better than prednisolone. Cyclosporine prevents T lymphocytes and immunoglobulin infusion helps to control the infection . Emmenegger and others have evidence that IVIG is effective in the treatment of HLH.47,48 A key finding of their analysis is the efficacy of IVIG if it is administered at the beginning (within hours) of the macrophage activation process and its failure in later stages of the disease. Etoposide has high activity in monocyte and histiocytic diseases. Patients who are at low risk may be treated with only cyclosporine, corticosteroid or IVIG, only high risk group required etoposide.26 Etoposide may be life saving specially in case of HLH with Ebstein Barr Viruses infection.17 CNS reactivation may occur during treatment, intrathecal Methotrexate plus Corticosteroid has been found to be beneficial in some cases. Serum ferritin seems to be a useful emergency marker for monitoring macrophage activation. Although symptoms and laboratory features improve within 2 to 3 weeks in some cases cytopenia may persist. In these cases bone marrow examination should be repeated to differentiate between non-response and myelosuppression due to etoposide. If there is no response, unlikely to have benefit with treatment. There is no established salvage regimen. Isolated patient has responded to Daclizumab, Alemtuzumab or to stem cell transplantation. Hasegawa et al reported remission of HLH after syngenic bone marrow transplantation.49 A recent study has found favorable long –term disease control in patients who received a reduced-intensity 456 conditioning regimen instead of conventional stem cell transplant.50 The Histiocyte Society in 1994 developed a common treatment protocol (HLH-94), primarily designed for the primary, inherited disease FHL. In January 2004 a revised HLH treatment protocol was opened entitled HLH-2004, which is based on HLH-94 with minor modifications. Cyclosporin A, that in HLH-94 was introduced at week 9, is instead initiated upfront, and corticosteroids is now combined with methotrexate in the intrathecal therapy. The aim is first to achieve a clinically stable resolution and ultimately to cure by BMT. The protocols have been widely accepted internationally and used in more than 25 countries and on all continents. There is a high remission rate on the HLH-94 and HLH-2004 treatment protocols, during which time a BMT donor usually can be identified. The overall prognosis with regard to survival improved dramatically during the last decade. One major problem is that many children still are diagnosed late, at a stage when they may have severe and irreversible brain damage. With regard to long-term survival, the prognosis will be dependent upon the results of BMT, which also are increasingly rewarding. REFERENCES 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. www.japi.org Scott R, Robb-Smith A. Histiocytic medullary reticulosis. Lancet 1939;2:194-8. Farquhar J, Claireaux A. Familial hemophagocytic reticulosis. Arch Dis Child 1952;27:519-25. Janka G. Familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Eur J Pediatr 1983;140:221-30. Ohadi M, Lalloz MR, Sham P, Zhao J, Dearlove AM, Shiach C, Kinsey S, Rhodes M, Layton DM Localization of a gene for familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis at chromosome 9q21.3-22 by homozygosity mapping. Am J Hum Genet 1999;64:165-71. Voskoboinik I, Thia MC, Trapani JA. A functional analysis of the putative polymorphisms A91V and N252S and 22 missense perforin mutations associated with familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Blood 2005;105: 4700-6. Ishii E, Ueda I, Shirakawa R, Yamamoto K, Horiuchi H, Ohga S, Furuno K, Morimoto A, Imayoshi M, Ogata Y, Zaitsu M, Sako M, Koike K, Sakata A, Takada H, Hara T, Imashuku S, Sasazuki T, Yasukawa M. Genetic subtypes of familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: correlations with clinical features and cytotoxic T lymphocyte/natural killer cell functions. Blood 2005;105:3442-8. Molleran Lee S, Villanueva J, Sumegi J, Zhang K, Kogawa K, Davis J, Filipovich AH. Characterisation of diverse PRF1 mutations leading to decreased natural killer cell activity in North American families with haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. J Med Genet 2004;41:137-44. Zur Stadt U, Beutel K, Kolberg S, Schneppenheim R, Kabisch H, Janka G, Hennies HC. Mutation spectrum in children with primary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: molecular and functional analyses of PRF1, UNC13D, STX11, and RAB27A. Hum Mutat 2006;27:62-8. Zur Stadt U, Schmidt S, Kasper B, Beutel K, Diler AS, Henter JI, Kabisch H, Schneppenheim R, Nurnberg P, Janka G, Hennies HC. Linkage of familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (FHL) type-4 to chromosome 6q24 and identification of mutations in © JAPI • VOL. 56 • JUNE 2008 syntaxin 11. Hum Mol Genet 2005;14:827-34. 10. Wong KF, Hui PK, Chan JK, Chan YW, Ha SY. The acute lupus hemophagocytic syndrome. Ann Intern Med 1991;114:387-90. 11. Kumakura S, Ishikura H, Munemasa S, Adachi T, Murakawa Y, Kobayashi S. Adult onset Still’s disease associated hemophagocytosis. J Rheumatol 1997;24:1645-8. 12. Morris JA, Adamson AR, Holt PJ, Davson J. Still’s disease and the virus-associated haemophagocytic syndrome. Ann Rheumatol Dis 1985;44:349-53. 13. Yasuda S, Tsutsumi A, Nakabayashi T, Horita T, Ichikawa K, Ieko M, et al. Haemophagocytic syndrome in a patient with dermatomyositis. Br J Rheumatol 1998;37:1357-8. 14. C h a n g C S , W a n g C H , S u I J , C h e n Y C , S h e n M C . Hematophagic histiocytosis: a clinicopathologic analysis of 23 cases with special reference to the association with peripheral T-cell lymphoma. J Formos Med Assoc 1994;93: 421-8. 15. Kadin ME, Kamoun M, Lamberg J. Erythrophagocytic T gamma lymphoma: a clinicopathologic entity resembling malignant histiocytosis. N Engl J Med 1981;304:648-53. 16. Yao M, Cheng A, Su I. Clinicopathological spectrum of haemophagocytic syndrome in Epstein-Barr virus-associated peripheral T-cell lymphoma. Br J Haematol 1994;87:535-43. 17. Gutiérrez A, Solano C, Ferrández A, Marugán I, Terol MJ, Benet I, Tormo M, Bea MD, Rodríguez J. Peripheral T-cell lymphoma associated consecutively with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis and hypereosinophilic syndrome. Eur J Haematol 2003;71:303–6. 18. Yang CW, Pan MJ, Wu MS, Chen YM, Tsen YT, Lin CL, et al. Leptospirosis: an ignored cause of acute renal failure in Taiwan. Am J Kidney Dis 1997;30:840-5. 19. Matzner Y, Behar A, Beeri E, Gunders A, Hershko C. Systemic leishmaniasis mimicking malignant histiocytosis. Cancer 1979;43:398-402. 20. Risdall RJ, McKenna RW, Nesbit ME, et al. Virus associated hemophagocytic syndrome: a benign histiocytic proliferation distinct from malignant histiocytosis. Cancer 1979;44: 993-1002. 21. Janka G, Imashuku S, Elinder G, SchneidernM Henter JL. Infection and malignancy associated hemophagocytic syndrome. Secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 1998;12:435-444. 22. L. Fardet, L Blum,, D. Kerob, F. Agbalika, L. Galicier, A. Dupuy et al. Human Herpesvirus 8 associated Hemophagocytic Lympho Histiocytosis in Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infected patients. Clinical Infectious Disease 2003;37:285-91. 23. Takahashi N, Chubachi A, Miura I, Nakamura S, Miura AB. Lymphoma associated hemophagocytic syndroms in Japan. Rinsho Ketsueki 1999;40:542-9. 24. Duval M, Fenneteau O, Doireau V, Faye A, Emilie D, Yotnda P, Drapier JC, et al. Intermittent hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis is a regular feature of lysinuric protein intolerance. J Pediatr 1999;134:236-9. 25. Arico M, Allen m, Brusa S, et al. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: proposal of a diagnostic algorithm based on perforin expression. Br J Haematol 2002;119:180-8. 26. Imashuku S, Teramura T, Morimoto A, Hibi S. Recent developments in the management of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2001;2: 1437-48. 27. Risma KA, Frayer RW, Fillipovich AH, Sumegi J. Aberrant maturation of mutant perforin underlies the clinical diversity of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. J Clin Invest 2006; 116:18292. 28. Katano H, Cohen JI. Perforin and lymphohistiocytic proliferative disorders. Br j Haematol 2005;128:739-50. 29. Rieux-Laucat F, Le deist F, De Saint Basile G. Autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome and perforin. N Engl J Med 2005;352:306-7. © JAPI • VOL. 56 • JUNE 2008 30. Arico M, Danesino C, Pende D, Moretta L. Pathogenesis of haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Br J Haematol 2001;114:761-9. 31. Jerome KR, Tait JF, Koelle DM, Corey L. Herpes simplex virus type 1 renders infected cells resistant to cytotoxic T cell induced apoptosis. J Virol 1998;72:436-41. 32. Poggi A, Costa p, Tomassaello E, Moretta L. IL-12 induced up regulation of NKRPIA expression in human NK cells and consequent NKRPIA mediated downregulation ofNK cell activation. Eur J Immunol 1998;28:1611-16. 33. Stephan Jl, Kone-Paut I, Galambrun C, Mouy R, Bader-Meunier B, Prieur AM. Reactive haemophagocytic syndrome in children with inflammatory disorders. A retrospective study of 24 patients. Rheumatology 2001;40:1285-92. 34. Ravelli A. Macrophage activation syndrome. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2002;14:548-52. 35. Villanueva J, Lee S, Giannini EH, et al. Natural killer cell dysfunction is adistinguishing feature of systemic onset juvenile rheumatoid arthritis and macrophage activation syndrome. Arthritis Res Ther 2005;7:R30-37. 36. Ramanan AV, Schneider R. Macrophage activation syndrome – whats in a name! J Rheumatol 2003;30:2513-6. 37. Athreya BH. Is macrophage activation syndrome a new entity? Clin Exp Rheumatol 2002;20:121-3. 38. Henter JI, Elinder G. Cerebromeningeal haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Lancet 1992;339:104-7. 39. Kieslich M, Vecchi M, Driever Ph, Laverda AM, Schwabe D, Jacobi G. Acute encephalopathy as aprimary manifestation of haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Dev Med Child Neurol 2001;43:555-8. 40. Morrell DS, Pepping MA, Scott JP, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Arch Dermatol 2002;138:1208-12. 41. Henter JI, Elinder G, Ost A. Diagnostic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. The FHL Study Group of the Histiocytic Society. Semin Oncol 1991;18:29-33. 42. Hafsteinsdottir S, Jonmundsson GK, Kristinsson Jr, et al. Findings in familial haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis prior to symptomatic presentation. Acta Paediatr 2002;91: 974-7. 43. Schneider EM, Lorenz I, Muller-Rosenberg M, Steinbach G, Kron M, Janka-Schaub GE. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis is associated with deficiencies of cellular cytolysis but normal expression og transcripts relevant to killer cell induced apoptosis. Blood 2002;100:2891-98. 44. Henter JI, Elinder G, Soder O, Ost A. Incidence in Sweden and clinical features of familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Acta Paediatr Scand 1991;80:428-35. 45. Reiner A, Spivak J. Hemophagocytic histiocytosis: a report of 23 new patients and a review of the literature. Medicine 1988;67:36988. 46. Sailler L, Duchayne E, Marchou B, Brousset P, Pris J, Massip P, et al. Aspects etiologiques des hemophagocytoses reactionnelles: etude retrospective chez 99 patients. Rev Med Interne 1997;18:855864. 47. Emmenegger U, Frey U, Reimers A, et al. Hyperferritinemia as indicator for intravenous immunoglobulin treatment in reactive macrophage activation syndromes. Am J Hematol 2001;68:4-10. 48. Larroche C, Bruneel F, André MH, et al. Intravenously administered gamma-globulins in reactive hemaphagocytic syndrome: Multicenter study to assess their importance, by the immunoglobulins group of experts of CEDIT of the AP-HP. Ann Med Interne 2000;151:533-9. 49. Hasegawa D, Sano K, KosakaY, Hayakawa A, Nakamura H. A case of haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis with prolonged remission after syngenic bone marrow transplantation, Bone Marrow Transplantation. 1999;24: 425-7. 50. Cooper N, Rao K, Gilmour K, et al. Stem cell transplantation with reduced-intensity conditioning for haemophagocytic www.japi.org 457

© Copyright 2026