Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa: An institutional analysis of 21 cases

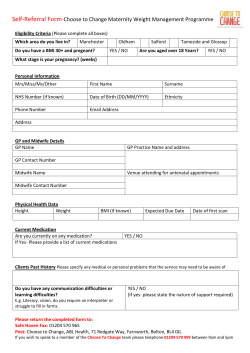

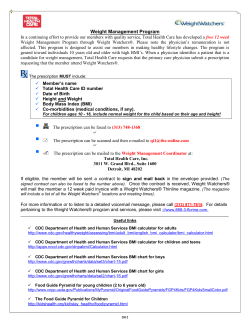

Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa: An institutional analysis of 21 cases Steven M. Dean, DO, FACP,a Matthew J. Zirwas, MD,b and Anthony Vander Horst, BA, BS, MAc Columbus, Ohio Background: Previous reports regarding elephantiasis nostras verrucosa (ENV) have been typically limited to 3 or fewer patients. Objectives: We sought to statistically ascertain what demographic features and clinical variables are associated with ENV. Methods: A retrospective chart review of 21 patients with ENV from 2006 to 2008 was performed and statistically analyzed. Results: All 21 patients were obese (morbid obesity in 91%) with a mean body mass index of 55.8. The average maximal calf circumference was 63.7 cm. Concurrent chronic venous insufficiency was identified in 15 patients (71%). ENV was predominantly bilateral (86%) and typically involved the calves (81%). Proximal cutaneous involvement (thighs 19%/abdomen 9.5%) was less common. Eighteen (86%) related a history of lower extremity cellulitis/lymphangitis and/or manifested soft-tissue infection upon presentation. Multisegmental ENV was statistically more likely in setting of a higher body mass index (P = .02), larger calf circumference (P = .01), multiple lymphedema risk factors (P = .05), ulcerations (P \ .001), and nodules (P \ .001). Calf circumference was significantly and proportionally linked to developing lower extremity ulcerations (P = .02). Ulcerations and nodules were significantly prone to occur concomitantly (P = .05). Nodules appeared more likely to exist in the presence of a higher body mass index (P = .06) and multiple lymphedema risk factors (P = .06). Limitations: The statistical conclusions were potentially inhibited by the relatively small cohort. The study was retrospective. Conclusions: Our data confirm the association among obesity, soft-tissue infection, and ENV. Chronic venous insufficiency may be an underappreciated risk factor in the genesis of ENV. ( J Am Acad Dermatol 2011;64:1104-10.) Key words: edema; elephantiasis; elephantiasis nostras verrucosa; lymphedema. E lephantiasis nostras verrucosa (ENV) is an uncommon and singular array of dermatologic manifestations that can complicate chronic lymphedema. Characteristic cutaneous signs include profound hyperkeratosis, dermal fibrosis, and lichenification, and a verrucous and papillomatous eruption with a cobblestone-like appearance From the Departments of Cardiovascular Medicinea and Dermatology,b Ohio State University College of Medicine; and Quantitative Research, Evaluation, and Measurement, Ohio State University School of Educational Policy and Leadership.c Funding sources: None. Conflicts of interest: None declared. Accepted for publication April 29, 2010. Reprint requests: Steven M. Dean, DO, FACP, Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Ohio State University College of 1104 Abbreviations used: BMI: body mass index CVI: chronic venous insufficiency ENV: elephantiasis nostras verrucosa Medicine, 200 Davis Heart and Lung Research Institute, 473 W 12 Ave, Columbus, OH 43210. E-mail: steven.dean@osumc. edu. Published online March 28, 2011. 0190-9622/$36.00 ª 2010 by the American Academy of Dermatology, Inc. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.04.047 Dean, Zirwas, and Horst 1105 J AM ACAD DERMATOL VOLUME 64, NUMBER 6 (Fig 1). The aforementioned array of dermatologic assess for both acute and chronic recanalized deep findings usually occurs in the presence of severe, venous thrombosis and venous incompetence. fibrotic edema that resists pitting. Recurrent cellulitis, Routinely obtained laboratory studies included: tumors, previous surgery or trauma, obesity, congescomprehensive chemistry profile, complete blood tive heart failure, and radiation are purported risk cell count, thyroid-stimulating hormone, free factors for ENV. However, concrete data regarding thyroxine-4, and urinalysis. When clinically approprithe epidemiology of this disorder are limited to ate, a transthoracic echocardiogram was obtained information attained from with attention to the right isolated case reports typically ventricular and pulmonary arCAPSULE SUMMARY involving 3 or fewer patients. tery systolic pressures. In an attempt to further Morbid obesity and soft-tissue infection elucidate the potential unRESULTS are the predominant risk factors for derlying risk factors for The sample of 21 patients elephantiasis nostras verrucosa (ENV). this disfiguring condition, an identified with ENV was ENV is principally bilateral and typically analysis of 21 affected pacomposed of 14 men and 7 involves the calves. Proximal cutaneous tients was undertaken from women. The mean age of involvement (thighs/abdomen) is less a university outpatient vascustudy participants and avercommon. lar medicine clinic. age duration of lymphedema was 54 years (range: 26-77 Chronic venous insufficiency was present METHODS years) and 11 years, respecin 71% of cases of ENV and often An assessment of 21 patively. All patients had bilatmanifested as concurrent stasis tients clinically given the dieral lymphedema. Although dermatitis, lipodermatosclerosis, agnosis of lower extremity one individual underwent a ulcerations, or a combination of these. ENV (2006-2008) was underbelow-knee amputation Venous hypertension may be an taken at a university vascular 1 year before presentation, underappreciated risk factor for ENV. medicine clinic. The diagnohe described a long-standing sis of ENV was made by recpresurgical history of bilatognizing the cutaneous characteristics in the setting eral ENV. of stage III lymphedema. All patients were examined The mean BMI was 55.8 (range: 34.6-79.1). All by a vascular medicine specialist certified by the study patients met criteria for obesity (BMI $ 30 American Board of Vascular Medicine. Cutaneous kg/m2) with 19 of the 21 patients (91%) fulfilling the criteria for morbid obesity (BMI $ 40). The average biopsy specimens were not routinely obtained. maximal calf circumference was 63.7 cm (range: Demographic data (age, gender, body mass index 43.2-106.7 cm). [BMI]) were acquired. Lymphedema-related clinical Characteristic ENV skin manifestations were revariables reviewed included: etiology, limb involvecorded in 18 of the 21 patients (86%) in a bilateral ment (unilateral/bilateral), maximal calf circumferfashion. In the 3 patients (14%) with unilateral ENV, ence (centimeters), and duration of swelling. the more swollen extremity was affected. All patients Patients were queried regarding a history of cellulitis manifested cobblestone-like plaques and papules and carefully inspected for evidence of acute softwith associated hyperkeratosis. Eleven patients tissue infection. (52%) with ENV had associated nodules as well. Recorded ENV-associated clinical findings reThe distribution of ENV cutaneous pathology is corded included: lesion distribution (toes, feet, outlined in Fig 2. Acute (n = 3) or previous (n = 8) calves, thighs, abdomen, or a combination of these) lower extremity venous stasis/lymphostatic ulceraand lesion type (papules, plaques, nodules). tions were identified in 11 patients (52%). Eighteen A papule was defined as an elevated solid lesion of the patients (86%) related a history of cellulitis up to 0.5 cm in diameter. A plaque was defined as a and/or manifested skin infection at the time of their circumscribed, plateaulike elevation above the skin examination. surface, often formed by the confluence of papules. Fifteen patients (71%) manifested concurrent A nodule was defined as a circumscribed, elevated, CVI according to the ClinicaleEtiologiceAnatomice solid lesion greater than 0.5 cm in diameter. Pathophysiologic classification criteria (Fig 3). Seven The ClinicaleEtiologiceAnatomicePathophysiologic of the 15 cases of clinically overt venous hypertension classification criteria were used to grade any associwere corroborated by ultrasonographically docuated physical findings of chronic venous insufficiency mented reflux. Superficial reflux within the bilateral (CVI).1 Bilateral lower extremity venous duplex ultrasonography was performed on all patients to above- and below-knee great saphenous vein was d d d 1106 Dean, Zirwas, and Horst J AM ACAD DERMATOL JUNE 2011 Fig 1. A 58-year-old obese man with classic skin findings of bilateral lower extremity elephantiasis nostras verrucosa including an admixture of plaques, papules, and nodules with a cobblestoned and mossy appearance in a multisegmental distribution (toes/feet/calves). identified in 7 cases with associated bilateral distal medial calf perforating vein reflux in two patients. No evidence of acute or chronic deep venous thrombosis was identified. Echocardiography documented mild to moderate pulmonary hypertension (right ventricular systolic pressure = 50-60 mm Hg) with normal left ventricular systolic function in 3 patients (14%). Statistical analysis Two types of correlations were reported. Pearson correlations for the continuous by continuous variables (age, BMI, average maximal calf circumference, lymphedema duration). The Pearson correlation was reported when both the column and row variables had a (P) identifier. The remaining data were assessed via Spearman correlations for the categorical by categorical variables. Significant results were defined at a level of significance of .05. Table I illustrates the statistical analyses of the aforementioned variables. Not surprisingly, there was a statistically significant (R = 0.79, P \ .001) relationship between the BMI and maximal (mean) calf circumference, with the calf circumference increasing roughly in proportion to BMI. Nearing statistical significance (R = 0.42, P = .06), a moderately positive relationship between BMI and the presence of nodules existed, suggesting a correlation between degree of obesity and risk for developing nodules. Finally, a significant correlation (R = 0.51, P = .02) between the BMI and anatomic distribution of ENV was identified. With increasing BMI, more areas of the lower extremity were affected by the cutaneous changes of ENV (henceforth referred to as multisegmental cutaneous involvement). As maximal calf circumference increased, patients were significantly more likely to incur both skin ulcerations (R = 0.52, P = .02) and multisegmental cutaneous involvement (R = 0.54, P = .01). The duration of lymphedema did not significantly correlate with complications of ENV such as nodules, ulcerations, or distribution. Men with ENV were more likely than women to have associated CVI (R = e0.67, P \.001). As the number of underlying risk factors (cellulitis, obesity, and pulmonary hypertension) for ENV increased, patients were significantly more likely to develop multisegmental cutaneous pathology (R = 0.44, P = .05). In addition, patients with multiple risk factors were probably more likely to develop nodules (R = 0.42, P = .06) although this relationship did not meet statistical significance. Lower extremity ulcerations (R = 0.62, P \ .001) and nodules (R = 0.77, P \ .001) were statistically more likely to exist in the presence of multisegmental cutaneous involvement. In addition, nodules and ulcerations were significantly prone to occur concurrently (R = 0.43, P = .05). A significant inverse correlation was identified between age and the two variables BMI and maximal calf circumference. For instance, younger patients had both larger calves (R = e0.525, P \ .015) and higher BMIs (R = e0.43, P = .051) than older patients. None of the patients had severe hypoalbuminemia, chronic liver disease, or end-stage renal disease. Patients with a history of hypothyroidism were euthyroid via thyroid-stimulating hormone and free thyroxine-4 testing at the time of their assessment. No cases of Graves disease were identified. DISCUSSION ENV is an uncommon, potentially disfiguring, and sometimes grotesque constellation of dermatologic sequelae of chronic lymphatic obstruction. Alternative terms for this disorder include ‘‘lymphostatic verrucosa,’’ ‘‘lymphostatic papillomatosis cutis,’’ ‘‘elephantiasis crurum papillaris et verrucosa,’’ and ‘‘mossy foot and/or leg.’’ Although morphologically comparable with classic filarial elephantiasis (eg, Wuchereria or Brugia species), ENV is a separate, nonparasitic mediated disorder. Semantically, the adjective ‘‘nostras’’ indicates ‘‘from our region’’ (temperate zone); consequently, nonfilarial elephantiasis or ENV is nosologically differentiated from classic tropical helminthic elephantiasis. In his seminal 1934 work, Castellani2 classified elephantiasis into 4 subtypes: (1) elephantiasis tropica, J AM ACAD DERMATOL Dean, Zirwas, and Horst 1107 VOLUME 64, NUMBER 6 Fig 2. Distribution of elephantiasis nostras verrucosa (ENV) cutaneous pathology. Fig 3. Chronic venous insufficiency subtypes in setting of elephantiasis nostras verrucosa according to ClinicaleEtiologiceAnatomicePathophysiologic classification criteria. caused by filariasis (eg, Wuchereria species); (2) elephantiasis nostras, secondary to recurrent bacterial cellulitis/lymphangitis; (3) elephantiasis symptomatica, caused by diverse conditions such as tuberculosis, syphilis, fungi, neoplasms, and surgery; and (4) elephantiasis congenita, in association with Milroy and Meige disease. However, more recent literature includes the aforementioned causes of elephantiasis symptomatica within the definition of ENV.3,4 Similarly, an argument could also be constructed for including patients with elephantiasis congenita and lymphostatic verrucosis within the ENV definition. 1108 Dean, Zirwas, and Horst J AM ACAD DERMATOL JUNE 2011 Table I. Statistical analysis of variables associated with elephantiasis nostras verrucosa BMI (P) BMI (P) Corr sig Calf (P) Corr sig Duration (P) Corr sig Gender Corr sig Etiology Corr sig Age (P) Corr sig Nodule Corr sig Ulcers Corr sig CVI Corr sig Dist Corr sig Calf (P) Duration (P) Gender Etiology Age (P) Nodule Ulcers CVI Dist 1 0.76 .00 1 0.07 .78 0.08 .72 1 0.18 .43 0.11 .64 0.15 .51 1 0.27 .23 0.30 .19 0.21 .36 0.06 .80 1 0.60 .00 0.58 .01 0.31 .17 0.16 .49 0.00 1.00 1 0.42 .06 0.29 .20 0.29 .20 0.07 .77 0.42 .06 0.00 1.00 1 0.24 .29 0.52 .02 0.21 .37 0.13 .56 0.25 .26 0.05 .84 0.43 .05 1 0.19 .41 0.04 .85 0.22 .34 0.67 .00 0.31 .17 0.01 .97 0.03 .90 0.24 .29 1 0.51 .02 0.54 .01 0.06 .80 0.01 .97 0.44 .05 0.20 .38 0.77 .00 0.62 .00 0.14 .54 1 BMI, Body mass index; Corr, correlation; CVI, chronic venous insufficiency; Dist, distribution; sig, significance. Two types of correlations were reported. Pearson correlation (P) was used for continuous by continuous variables (BMI, maximal calf circumference, lymphedema duration, and age). Remaining results were reported via Spearman correlations for categorical by categorical variables. For results that show significance at 95% confidence level, both correlation coefficient (r) and P value (sig) are bolded. Regardless of the aforementioned subtype, the theory of Castellani5 suggests that all forms of elephantiasis share a common pathogenic mechanism. Specifically, recurrent streptococcal (less often staphylococcal) lymphangitis is the ultimate precipitant of elephantiasis. Even in the setting of filariasis, Castellani5 proposed that parasitic burden traumatizes the lymphatic vessels, thereby allowing secondary bacterial lymphangitis to provoke elephantiasis. The precipitating events in ENV are speculative but are probably a result of occult or clinically manifest disruption of the skin barrier from cutaneous fissures, erosions, ulcerations, and/or tinea-associated interdigital fissures. Consequently, a nidus for bacterial infection is created. With each bacterial infection, increasing lymphatic stasis ensues with progressive accumulation of proteins, lymphocytes, and cellular metabolites. Fibroblasts proliferate and collagen is deposited with subsequent epidermal, dermal, and subcutaneous thickening. Consequently, the limb becomes progressively swollen and increasingly susceptible to additional bouts of soft-tissue infection. Attendant local immune dysfunction further increases susceptibility to cellulitis. Because of this vicious cycle of swelling and infection, classic ENV eventuates. Our data support the role of recurrent soft-tissue infection in the genesis of ENV, as 86% of the patients presented with either acute lower extremity cellulitis or described a history of soft-tissue infection. However, the association between recurrent cellulitis and ENV does not appear absolute because 14% of the patients had no history of infection. Case reports of ENV evolving in the absence of cellulitis or lymphangitis exist.6 Our study highlights the importance of two lesser appreciated factors in the setting of ENV, specifically obesity and CVI. All 21 patients were obese with 91% J AM ACAD DERMATOL Dean, Zirwas, and Horst 1109 VOLUME 64, NUMBER 6 of them meeting criteria for morbid obesity (BMI $ 40). The mean BMI was an astounding 55.8 with an average maximal calf circumference of a remarkable 63.7 cm (25 in). Although several studies have illustrated that obesity enhances the risk of postmastectomy lymphedema,7,8 an explicit association between obesity and lower extremity lymphedema has not been well documented in the medical literature. In a 2008 article, deidentified data from 17 wound care centers within the United States (approximately 15,000 patients) documented a 74% prevalence of lower extremity lymphedema in morbidly obese patients.9 The pathophysiological mechanisms that link obesity and lymphedema are speculative but may involve structural lymphatic changes in the interstitium, impaired diaphragmatic movement, increased abdominal pressure, and/or arteriovenous proliferation within oxygen-demanding fat tissue without proportional lymphatic proliferation. A definite answer as to what provokes ENV to develop in the setting of obesity and lymphedema is cryptic, although our data support the theory of Castellani5 that superimposed soft-tissue infection may be causative. Multiple small case reports (n = # 2 patients) of patients with ENV have documented the potentially culpable combination of obesity and recurrent cellulitis, lymphangitis, or both.3,10-12 Obesity is often implicated as a risk factor for CVI; consequently, it is not surprising that 15 of our patients (71%) manifested clinical (and often ultrasonographic) signs of venous hypertension. Many patients displayed more advanced ClinicaleEtiologiceAnatomicePathophysiologic features, as evidenced by stasis pigmentation (IVa) in 14 (67%) and chronic stasis-associated sclerosing panniculitis/lipodermatosclerosis (IVb) in 9 (43%). The relationship between lymphedema and CVI has been noted by other authors via various objective tests13-16 or clinical observation.17,18 CVI may be an underrecognized factor in the pathogenesis of ENV. Curiously, we uncovered a significant inverse relationship between age and the variables BMI and maximal calf circumference. Younger patients were more obese with larger calves. This converse association may simply reflect the recent increasing mean BMI in the United States. For example, the percentage of male subjects with a BMI greater than or equal to 30 kg/m2 in the original (1948-1953), offspring (1971-1975), and third-generation (2002-2005) cohorts of the Framingham Heart Study was 12%, 15%, and 26%, respectively.19 Because of the paucity of reported cases, no evidence-based medicine exists to guide therapy of ENV. Management is based on limited data from case reports. Treatment includes traditional modalities used in lymphedema, including skin hygiene, limb elevation, manual lymphatic drainage/complete decongestive therapy, compression bandages, graduated support stockings, and sequential intermittent lymphatic pumping. Two case reports documented attenuation in both leg swelling and skin changes with the use of sequential lymphatic pumping.17,20 Considering that obesity and cellulitis appear closely linked to ENV, weight loss and infection control are paramount clinical goals. Both topical and systemic retinoids have been successfully used to mitigate the cutaneous manifestations of ENV.6,21 Two case reports illustrated favorable results with the use of scalpel debridement.22,23 In one of these surgical reports, adjunctive dermabrasion with a motorpowered grinder was used.22 A lymphaticovenular anastomosis effectively reduced limb swelling and skin lesions in one patient with ENV.24 As a last resort, amputation is sometimes required.12,25 Conclusion We have reported the largest series to date on the combined cutaneous and vascular malady ENV. In a statistical fashion, our data illustrate how many pathophysiological variables interact in this disfiguring disorder. ENV was predominantly a distal disorder (81%) that affected the calves (either in isolation or in combination with the feet and toes) and was typically bilateral (86%). Proximal involvement of the thigh and abdominal wall occurred in only 19% and 10% of the patients, respectively. Multisegmental cutaneous pathology was statistically more likely to occur in the presence of a higher BMI, larger calf circumference, multiple risk factors (eg, cellulitis, obesity, pulmonary hypertension, or a combination of these), ulcerations, and nodules. Calf circumference was significantly and proportionally linked to developing lower extremity ulcerations. Nodules and ulcerations were significantly prone to occur simultaneously. An elevated BMI and multiple risk factors appeared to increase the chance of manifesting nodules but these relationships fell short of being statistically significant (P = .06), probably because of an inadequate sample size. Although severe obesity and soft-tissue infection appeared inexorably linked in the genesis of ENV, associated CVI may have been an underappreciated participant in causation as well. As the proportion of obese patients in the United States increases, the probability of developing both lymphedema and its disfiguring sequel, ENV, is expected to increase as well. Our facility will continue to enroll patients in an ENV database in an effort to obtain more information on this distinct and unfortunate condition. 1110 Dean, Zirwas, and Horst J AM ACAD DERMATOL JUNE 2011 REFERENCES 1. Porter JM, Moneta GL, International Consensus Committee on Chronic Venous Disease. Reporting standards in venous disease: an update. J Vasc Surg 1995;21:635-45. 2. Castellani A. Elephantiasis nostras. J Trop Med Hyg 1934;37: 257-64. 3. Schissel D, Hivnor C, Elston DM. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa. Cutis 1998;62:77-80. 4. Routh HB. Elephantiasis. Int J Dermatol 1992;31:845-52. 5. Castellani A. Researches on elephantiasis nostras and elephantiasis tropica with regard to their initial stage of recurring lymphangitis (lymphangitis recurrens elephantogenica). J Trop Med Hyg 1969;72:89-96. 6. Zouboulis CC, Biczo S, Gollnick H, Reupke HJ, Rinck G, Szabo M, et al. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa: beneficial effect of oral etretinate therapy. Br J Dermatol 1992;127:411-6. 7. Petrek JA, Senie RT, Peters M, Rosen PP. Lymphedema in a cohort of breast carcinoma survivors 20 years after diagnosis. Cancer 2001;92:1368-77. 8. McLaughlin SA, Wright MJ, Morris KT, Giron GL, Sampson MR, Brockway JP, et al. Prevalence of lymphedema in women with breast cancer 5 years after sentinel lymph node biopsy or axillary dissection: objective measurements. J Clin Oncol 2008; 10(26):5213-9. 9. Fife CE, Carter MJ. Lymphedema in the morbidly obese patient: unique challenges in a unique population. Ostomy Wound Manage 2008;54:44-56. 10. Dean SM. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa. Vasc Med 2000;5: 261. 11. Fife CE, Benavides S, Carter MJ. A patient-centered approach to treatment of morbid obesity and lower extremity complications: an overview and case studies. Ostomy Wound Manage 2008;54:20-2, 24-32. 12. Schiff BL, Kern AB. Elephantiasis nostras. Cutis 1980;25:88-9. 13. Collins PS, Villaviecencio JL, Abreu SH, Gomez ER, Coffey JA, Connaway C, et al. Abnormalities of lymphatic drainage in lower extremities: a lymphoscintigraphic study. J Vasc Surg 1989;9:145-52. 14. Weissleder H, Weissleder R. Lymphedema: evaluation of qualitative and quantitative lymphoscintigraphy in 238 patients. Radiology 1988;167:729-35. 15. Kim DI, Huh S, Hwang JH, Lee BB. Venous dynamics in leg lymphedema. Lymphology 1999;32:11-4. 16. Saito T, Hosoi Y, Onozuka A, Komiyama T, Miyata T, Shigematsu H, et al. Impaired ambulatory venous function in lymphedema assessed by near-infrared spectroscopy. Int Angiol 2005;24:336-9. 17. Rowley MJ, Rapini RP. Elephantiasis nostras. Cutis 1992;49: 91-6. 18. Alexander JW, Rowan L, Cafiero M, Sujeta N, Conroy S, Tyler RD, et al. Roundtable discussion: does skin care for the obese patient require a different approach? Bariatr Nurs Surg Patient Care 2006;1:157-65. 19. Splansky GL, Corey D, Yang Q, Atwood LD, Cupples LA, Benjamin EJ, et al. The third generation cohort of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s Framingham heart study: design, recruitment, and initial examination. Am J Epidemiol 2007;165:1328-35. 20. Beninson J, Redmond MJ. Mossy legean unusual therapeutic success. Angiology 1986;37:642-6. 21. Boyd J, Sloan S, Meffert J. Elephantiasis nostrum verrucosa of the abdomen: clinical results with tazarotene. J Drugs Dermatol 2004;3:446-8. 22. Iwao F, Sato-Matsumura KC, Sawamura D, Shimizu H. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa successfully treated by surgical debridement. Dermatol Surg 2004;30:939-41. 23. Ferrandiz L, Moreno-Ramirez D, Perez-Bernal A, Camacho F. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa treated with surgical debridement. Dermatol Surg 2005;31:731. 24. Motegi S, Tamura A, Okada E, Nagai Y, Ishikawa O. Successful treatment with lymphaticovenular anastomosis for secondary skin lesion of chronic lymphedema. Dermatology 2007;215: 147-51. 25. Turhan E, Ege A, Kese S, Bayar A. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa complicated with chronic tibial osteomyelitis. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2008;128:1183-6.

© Copyright 2026