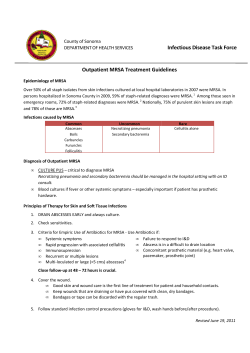

clinic e th Cellulitis and

in the clinic ® in the clinic Cellulitis and Soft-Tissue Infections Physician Writers Lawrence J. Eron, MD Section Editors Christine Laine, MD, MPH David R. Goldmann, MD Harold C. Sox, MD Prevention page ITC1-2 Diagnosis page ITC1-4 Treatment page ITC1-7 Practice Improvement page ITC1-14 CME Questions page ITC1-16 The content of In the Clinic is drawn from the clinical information and education resources of the American College of Physicians (ACP), including PIER (Physicians’ Information and Education Resource) and MKSAP (Medical Knowledge and Self-Assessment Program). Annals of Internal Medicine editors develop In the Clinic from these primary sources in collaboration with the ACP’s Medical Education and Publishing Division and with the assistance of science writers and physician writers. Editorial consultants from PIER and MKSAP provide expert review of the content. Readers who are interested in these primary resources for more detail can consult http://pier.acponline.org and other resources referenced in each issue of In the Clinic. The information contained herein should never be used as a substitute for clinical judgment. © 2008 American College of Physicians ellulitis is an infection of the skin and underlying tissues. It may follow a break in the skin or a surgical wound but may also occur without an obvious inciting event. The microorganisms most frequently involved include group A streptococci (Streptococcus pyogenes); groups B, C, and G β-hemolytic streptococci; and Staphylococcus aureus. Over recent decades, cellulitis has challenged clinicians in several ways. First, physician visits for cellulitis and soft-tissue infections have increased from 32 to 48 visits per 1000 population from 1997 to 2005 (1). Second, necrotizing fasciitis due to group A streptococci is now endemic in the United States. Third, S. aureus, the predominant cause of cellulitis accompanied by abscesses or wound drainage, has become increasingly resistant to methicillin, requiring vancomycin and other, newer antimicrobial agents. A particular communityacquired methicillin-resistant S. aureus (CA-MRSA) strain, USA 300, is replacing nosocomial strains of MRSA in hospitals (2). C Prevention 1. Hersh AL, Chambers HF, Maselli JH, et al. National trends in ambulatory visits and antibiotic prescribing for skin and soft-tissue infections. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1585-91. [PMID: 18663172] 2. King MD, Humphrey BJ, Wang YF, et al. Emergence of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus USA 300 clone as the predominant cause of skin and soft-tissue infections. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:30917. [PMID: 16520471] 3. Semel JD, Goldin H. Association of athlete’s foot with cellulitis of the lower extremities: diagnostic value of bacterial cultures of ipsilateral interdigital space samples. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;23:1162-4. [PMID: 8922818] 4. Parish LC, Jorizzo JL, Breton JJ, et al. Topical retapamulin ointment (1%, wt/wt) twice daily for 5 days versus oral cephalexin twice daily for 10 days in the treatment of secondarily infected dermatitis: results of a randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:1003-13. [PMID: 17097398] © 2008 American College of Physicians What factors increase the risk for cellulitis and soft-tissue infections? Any injury to the skin may lead to cellulitis or soft-tissue infections. Human or animal bites have an especially high risk for subsequent infection. Crush injuries and open fractures, particularly those with vascular injury or gross contamination with soil, are likely to become infected. Patients with comorbid conditions that predispose them to infection (see Box) are also at increased risk for cellulitis. A past episode of streptococcal cellulitis puts patients at risk for recurrences, especially if tinea pedis is present (3). Recurrent cellulitis is also common in patients with chronic venous insufficiency, radical mastectomy with axillary lymph node dissection, or a coronary artery bypass graft with saphenous vein harvesting. How can patients decrease their chances of developing cellulitis and soft-tissue infections? Wounds due to minor traumatic injuries should be meticulously cleaned with antibacterial soap. Application of neomycin (or mupirocin ointment when MRSA is suspected) may be helpful in patients with comorbid conditions that predispose them to infection. ITC1-2 In the Clinic Although it is not an approved indication, retapamulin ointment is an option when mupirocin-resistant MRSA is suspected or proven (4). Major traumatic wounds, including crush injuries and open fractures, should be cleansed with copious saline irrigation and, if necessary, surgical debridement with repair of injured vessels. Wounds should be left open to heal by secondary intention. Antimicrobial prophylaxis should be administered according to recommendations for the type of injury (5). Patients with recurrent lowerextremity cellulitis should be inspected for tinea pedis, which should be treated if present. Risk Factors for Cellulitis and Soft-Tissue Infection • Trauma (lacerations, burns, abrasions, crush injuries, open fractures) • Intravenous drug use • Human or animal bites • Conditions that predispose to infection (diabetes, arterial insufficiency, chronic venous insufficiency, lymphedema, chronic renal disease, cirrhosis, neutropenia, and hypogammaglobulinemia) • Past streptococcal cellulitis (especially if tinea pedis is present) • Radical mastectomy with axillary dissection • Saphenous vein harvesting Annals of Internal Medicine 6 January 2009 Which strategies reduce the risk for cellulitis and soft-tissue infections in patients with diabetes? Patients with diabetes should receive education about proper foot care and should regularly inspect their feet to promptly recognize problem areas. Treatment of superficial plantar ulcers with aggressive cleansing and off-weighting of the ulcerated area may prevent subsequent infection. Plantar calluses should be shaved down. Multidisciplinary foot-care teams may be helpful (6). Which strategies decrease cellulitis and soft-tissue infections after mammalian bites? Bite wounds should be thoroughly cleansed. Clinicians should administer amoxicillin and clavulanate for prophylaxis of closed-fist injuries and cat bites and should consider doing so for other bites when there is extensive injury to soft tissue or when the bite site is near a joint or bone. For patients allergic to penicillin, use moxifloxacin plus clindamycin. Doxycycline may also be used for prophylaxis of cat bites. A 2001 review of 8 randomized, controlled trials compared antibiotics with placebo or no treatment to prevent infection following mammalian bites. Overall, the use of antibiotics was associated with a statistically significant reduction in infection following human bites but not cat or dog bites. In addition, in analyses of any mammalian bite to the hand, prophylactic antibiotics reduced the rate of infection (odds ratio, 0.20 [95% CI, 0.01 to 0.86]) (7). Avoid suturing bite wounds closed except if the wounds are on the face. Wound edges may be approximated with sterile adhesive strips or closed by delayed primary closure. If sutures are necessary, then antimicrobial prophylaxis and close follow-up are indicated. 6 January 2009 Annals of Internal Medicine Which interventions decrease the risk for cellulitis and soft-tissue infections associated with surgical wounds? Surgical site infections develop in 2% to 5% of all surgical procedures. To prevent them, health care providers must practice good hand hygiene, proper preparation of the patient’s skin, and good surgical technique (see Box). Proper perioperative antimicrobial prophylaxis, administered within 1 hour before surgical incision, also prevents surgical wound infection. Recommendations are for singledose administration or multiple doses to end within 24 hours following the end of surgery (see Box) (8). What is the role of surveillance to identify patients with MRSA colonization or infection? Although MRSA can occur in anyone, athletes, men who have sex with men, incarcerated individuals, and people living in public housing are at greater risk for MRSA infection than are other populations (9). In the United States, 126 000 hospitalized patients are infected by MRSA each year, and 5000 die as a result. To reduce these staggering numbers, it would seem that clinicians should identify and isolate patients who are colonized or infected with MRSA. However, the connection between colonization and infection and the effectiveness of decolonization in reducing infection are unclear. The cost-efficacy of active surveillance cultures to identify MRSA carriers is also controversial (10). A study of 812 U.S. soldiers evaluated changes over time in communityacquired MRSA colonization by collecting nasal swabs for S. aureus cultures at baseline and 8 to 10 weeks later while observing for soft-tissue infections. At baseline, 24 (3%) participants were colonized with CA-MRSA and 229 (28%) with methicillinsensitive S. aureus (MSSA). Of those with CA-MRSA, 9 (38%) developed soft-tissue infection compared with 8 (3%) with MSSA (relative risk, 10.7 [CI, 4.6 to 25.2]). At In the Clinic ITC1-3 Surgical Techniques that Reduce the Postoperative Infection Rate • Proper skin preparation • Gentle traction during surgery • Effective hemostasis • Removal of devitalized tissues • Obliteration of dead space • Irrigation of tissues • Fine, nonabsorbable monofilament suture material • Closed-suction drains • Wound closure without tension Antimicrobial Prophylaxis in Surgery • Cefazolin or cefuroxime for clean surgical procedures (Clindamycin or vancomycin for patients with penicillin allergy) • Cefoxitin, ampicillin/ sulbactam, or metronidazole/cefazolin for gastrointestinal surgery (Clindamycin or vancomycin plus aztreonam or ciprofloxacin for patients with penicillin allergy) 5. Holtom PD. Antibiotic prophylaxis: current recommendations. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2006;14:S98S100. [PMID: 17003220] 6. Lipsky BA, Berendt AR, Deery HG, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America. Diagnosis and treatment of diabetic foot infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:885-910. [PMID: 15472838] 7. Medeiros I, Saconato H. Antibiotic prophylaxis for mammalian bites. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001:CD001738. [PMID: 11406003] 8. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. Antibiotic prophylaxis in surgery. Guideline No 104; 2008. Accessed at www.sign.ac.uk/guid elines/fulltext/104/in dex.html on 11 November 2008. © 2008 American College of Physicians follow-up, CA-MRSA colonization had decreased to 1.6% without eradication efforts (11). 9. Diep BA, Chambers HF, Graber CJ, et al. Emergence of multidrugresistant, communityassociated, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clone USA300 in men who have sex with men. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:249-57. [PMID: 18283202] 10. Webster J, Osborne S. Preoperative bathing or showering with skin antiseptics to prevent surgical site infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007:CD004985. [PMID: 17443562] 11. Ellis MW, Hospenthal DR, Dooley DP, et al. Natural history of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus colonization and infection in soldiers. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:971-9. [PMID: 15472848] 12. Harbarth S, Fankhauser C, Schrenzel J, et al. Universal screening for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus at hospital admission and nosocomial infection in surgical patients. JAMA. 2008;299:1149-57. [PMID: 18334690] 13. Karchmer TB, Durbin LJ, Simonton BM, et al. Cost-effectiveness of active surveillance cultures and contact/droplet precautions for ` control of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Hosp Infect. 2002;51:126-32. [PMID: 12090800] 14. Simor AE, Phillips E, McGeer A, et al. Randomized controlled trial of chlorhexidine gluconate for washing, intranasal mupirocin, and rifampin and doxycycline versus no treatment for the eradication of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus colonization. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:178-85. [PMID: 17173213] In a prospective crossover study in which patients were assigned to either polymerase chain reaction testing of specimens from their nares or no polymerase chain reaction testing, the incidence of nosocomial MRSA infection was 1.11 per 1000 patient-days compared with 1.20 in control participants, a nonsignificant difference (12). A study examining the cost-effectiveness of active surveillance cultures and barrier precautions for controlling MRSA in neonatal intensive care units of 2 hospitals found that identifying colonized patients and implementing preventive measures was cost-effective (13). Although there is evidence that MRSA carriers can be decolonized, the net benefit of decolonization is uncertain and decolonization through the use of topical antimicrobials applied to the nares is not always successful (14). A review addressing eradication strategies for MRSA found insufficient evidence to support the use of topical or systemic antimicrobial therapy or combinations of these agents for eradicating nasal or extranasal MRSA and identified the potential for serious adverse events and the development of antimicrobial resistance (15). Prevention... Prevention of cellulitis and soft-tissue infection is best accomplished by thorough cleansing of wounds and, when indicated, antimicrobial prophylaxis. In patients with diabetes, examination of the plantar surface of the foot and proper early management of lesions prevents the development of infection. Central principles in the prevention of surgical site infections are good hand hygiene, good surgical technique, and appropriate use of perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis. The jury is still out on the net benefits of active surveillance of MRSA carriers with identification and decolonization. CLINICAL BOTTOM LINE Diagnosis © 2008 American College of Physicians What is the role of the history and physical examination in the diagnosis of cellulitis and softtissue infections? A careful history is important in determining the potential cause of the infection. See Box for microorganisms associated with specific clinical situations. Skin infection has many causes, and other conditions may mimic infection (Table 1). The physical examination helps to differentiate cellulitis from other diagnoses and to determine the potential causes if cellulitis is present. The absence of drainage or abscess formation makes streptococci a likely cause, as do lymphangitis, a raised indurated border, and a peau d’orange appearance of the skin. S. aureus is more likely when abscess, draining ITC1-4 In the Clinic wounds, or penetrating trauma are present (16). Crepitus suggests Pathogens Associated With Clinical Scenarios • Diabetes: Staphylococcus aureus, group B streptococci, anaerobes, gram-negative bacilli • Cirrhosis: Campylobacter fetus, coliforms, Vibrio vulnificus, Capnocytophaga canimorsus • Neutropenia: Pseudomonas aeruginosa • Human bite: Eikenella corrodens • Cat bite: Pasteurella multocida • Dog bite: P. multocida, C. canimorsus • Rat bite: Streptobacillus moniliformis • Hot tub exposure: P. aeruginosa • Fresh water laceration: Aeromonas hydrophila • Fish tank exposure: Mycobacterium marinum • IV drug use: MRSA, P. aeruginosa Annals of Internal Medicine 6 January 2009 infection by gas-producing organisms, such as an anaerobic bacteria or a gram-negative bacillus. A foul odor may indicate infection by anaerobic microorganisms, whereas a sweet odor may indicate the presence of Pseudomonas or clostridial species. Impetigo is characterized by blisters and sores on the face or extremities, is due to streptococci or staphylococci (S. aureus has become predominant in recent years), and usually occurs in children. Necrotizing fasciitis involves deeper tissue planes (fascia and muscle), whereas less-severe forms involve subcutaneous tissue (cellulitis) or epidermis and dermis (erysipelas) (Figure). Clinicians must differentiate limbthreatening infection, such as necrotizing fasciitis, from non–limb-threatening superficial cellulitis, because the former requires hospitalization whereas outpatient treatment is usually sufficient for the latter (17). See Box Table 1. Other Conditions to Consider in the Differential Diagnosis of Cellulitis and Soft-Tissue Infection Disease Characteristics Myositis due to viruses or parasites Mild-to-moderate fever. Severe, diffuse pain and little to no localized pain. Mild systemic toxicity. No gas in tissues. No obvious portal of entry. Deep venous thrombophlebitis Deep pain, usually in the calf. Not usually associated with fever, chills, or reddened skin. Hemodynamic instability with pulmonary embolism. Septic arthritis Fever. Exquisitely painful range of motion. Olecranon bursa infection Redness, tenderness, fluctuance, nonpainful range of motion. Toxic epidermal necrolysis Mucous membrane and diffuse cutaneous involvement. Bullae and sloughing of skin. History of drug exposure. Hypersensitivity reaction Usually localized. Insect bite might be present. Contact dermatitis Look for unusual patterns of distribution. There is no fever, but pruritis is present. Exposure to irritant. Pyoderma gangrenosum Usually on the anterior shin. Frequently acute bluishblack discoloration. Ragged ulcers with undermined edges. Often underlying inflammatory bowel disease. Herpetic whitlow Vesicles on digits with associated pain, redness, and swelling; frequently accompanied by lymphangitic streaking. Sometimes occupational (for example, dental hygienist, anesthesiologist). Erythema migrans (Lyme disease) Resembles erysipelas, but is not painful and progresses slowly, and fever is less marked. Early herpes zoster (before Pain and erythematous papules precede vesicle formation. vesicles appear) Hair follicle Crust Sebaceous gland Bullae Vesicle Stratum corneum Erysipelas Stratum germinativum Dermal papillae Cellulitis Post capillary venule Subcutaneous fat Deep fascia Lymphatic channel Vein Necrotizing fasciitis Artery Myositis Bone Muscle Figure. Anatomy of Skin and Soft Tissues and Different Types of Skin and Soft-Tissue Infections. 6 January 2009 Annals of Internal Medicine In the Clinic ITC1-5 15. Loeb M, Main C, Walker-Dilks C, et al. Antimicrobial drugs for treating methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus colonization. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003:CD003340. [PMID: 14583969] 16. Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft-tissue infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:1373-406. [PMID: 16231249] 17. Bisno AL, Cockerill FR 3rd, Bermudez CT. The initial outpatient-physician encounter in group A streptococcal necrotizing fasciitis. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:607-8. [PMID: 10987730] 18. Anaya DA, Dellinger EP. Necrotizing softtissue infection: diagnosis and management. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:705-10. [PMID: 17278065] © 2008 American College of Physicians Physical Examination Findings that Suggest Necrotizing Fasciitis • Rapid increase in size of the infected area • Evolution of violaceous bullae • A reddish-purple discoloration of the skin • Woody induration of the infected area • A pale appearance of the infected area rather than erythema • Pain or severe tenderness out of proportion to the appearance of the cellulitis • Severe systemic toxicity • Sepsis syndrome Table 2. Laboratory and Other Studies for Evaluating Cellulitis and Soft-Tissue Infection Test Notes CBC, differential, and platelet count Elevated leukocyte count with marked left shift suggests deep-seated or systemic infection. Decreased platelet count suggests bacteremia, the toxic shock syndrome, or gas gangrene. Leukemoid reaction (>50 000) and hemoconcentration (rising hematocrit, frequently >60) suggests Clostridium sordellii infection. Low hematocrit, increased LDH, and intravascular hemolysis suggest C. perfringens infection. Elevated creatinine concentration suggests group A streptococcal or clostridial myonecrosis or the toxic shock syndrome. Elevated glucose level suggests underlying diabetes mellitus. Elevated CPK concentration suggests rhabdomyolysis, clostridial or streptococcal myonecrosis, or necrotizing fasciitis. Low serum bicarbonate concentration suggests metabolic acidosis and septic shock. Alternatively, in a patient with diabetes, metabolic acidosis associated with any soft-tissue infection suggests an aggressive process. A low or decreasing albumin level suggests a diffuse capillary leak syndrome. Subsequent soft-tissue swelling, third spacing, and pulmonary edema may result. A low serum calcium level suggests staphylococcal or streptococcal toxic shock syndrome or necrotizing fasciitis. Useful to detect gas in tissue and may also show underlying fracture, osteomyelitis, or foreign body. May be useful to localize the site, discern the extent of disease, and provide for early diagnosis of necrotizing infections. With necrotizing fasciitis caused by group A streptococcus, distortion or thickening of the fascia with fluid accumulation can occur in children. In adults, CT is better than ultrasonography at defining the extent of disease. The definitive test for identification of the cause of infection. Serum creatinine Serum glucose Serum CPK Serum bicarbonate Serum albumin Serum calcium Radiography CT or MRI Ultrasonography Culture and sensitivity testing CBC = complete blood count; CPK = creatine phosphokinase; CT = computed tomography; LDH = lactic dehydrogenase; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging. for physical examination clues to necrotizing fasciitis. 19. Arslan A, PierreJerome C, Borthne A. Necrotizing fasciitis: unreliable MRI findings in the preoperative diagnosis. Eur J Radiol. 2000;36:139-43. [PMID: 11091013] 20. Eron LJ, Lipsky BA. Use of cultures in cellulitis: when, how, and why? [Editorial]. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2006;25:615-7. [PMID: 16896821] 21. Zahar JR, Goveia J, Lesprit P, et al. Severe soft tissue infections of the extremities in patients admitted to an intensive care unit. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2005;11:79-82. [PMID: 15649312] © 2008 American College of Physicians What is the role of laboratory testing in the diagnosis of cellulitis and soft-tissue infections? Laboratory testing is useful to judge the severity of infection and to guide therapy (Table 2). Appropriate laboratory tests include blood cultures; complete blood count with differential; and chemistries, including a creatinine, blood urea nitrogen, creatine phosphokinase, glucose, electrolytes (especially the bicarbonate), and calcium. Patients with lower extremity cellulitis should also be evaluated for tinea pedis. tissue. Magnetic resonance imaging is more sensitive than CT for detecting edema but may be less useful in differentiating between cellulitis and necrotizing fasciitis because of their low specificity (18,19). Results of wound and blood cultures may guide antibiotic choices but are positive in less than 5% of cases (16, 20). Aspiration or punch biopsies are reported to yield positive cultures in 2% to 40% of cases (21), with the lower figure being closer to most clinical experience. However, among patients with streptococcal toxic shock syndrome, 60% have positive blood cultures (21). Computed tomography (CT) is more sensitive and specific than plain radiographs in identifying gas in Although bullae and vesicles due to streptococcal toxic shock syndrome may yield positive cultures, those ITC1-6 Annals of Internal Medicine In the Clinic 6 January 2009 Types of Necrotizing Fasciitis due to nonnecrotizing infection by streptococci are sterile. Streptococcal infection, although highly inflammatory, is paucibacterial. In the future, polymerase chain reaction technology may permit rapid identification of pathogens that are difficult to culture. When should clinicians consult an interventional radiologist or surgeon during the evaluation of cellulitis and soft-tissue infection? Patients with necrotizing fasciitis require early surgical inspection of the deep tissues through a small incision that allows evaluation of the condition of the fascia and the viability of underlying musculature. Diagnostic incisions can be extended to perform radical debridement, should necrotizing infection be visible. Other signs suggesting the need for surgical intervention include drainage, thrombosed vessels, and lack of resistance to finger dissection in normally adherent tissues (18). Interventional radiologists can use diagnostic imaging to locate, biopsy, and aspirate deep collections or masses for diagnostic purposes as well as for therapeutic drainage but cannot inspect wounds macroscopically or debride devitalized tissue. • Necrotizing fasciitis type 1: Mildto-moderate fever and systemic toxicity. Little to no diffuse pain and mild-to-moderate localized pain. Mild-to-moderate gas in tissues. Portal of entry usually obvious. Higher risk with diabetes (S. aureus, group B streptococci, anaerobes, and gram-negative bacilli). • Necrotizing fasciitis type 2 (“flesh-eating strep”): Moderateto-severe fever. Little to no diffuse pain and severe localized pain. Severe systemic toxicity. No gas in tissues. Portal of entry not obvious in 50% of cases (commonly streptococci). • Necrotizing fasciitis type 3 (“gas gangrene”): Moderate fever. Little to no diffuse pain and severe localized pain. Severe systemic toxicity. Severe gas in tissues. Portal of entry usually obvious (clostridial species). Diagnosis... Clinicians must use the medical history, physical examination, and laboratory testing to identify probable pathogens. Culture identification of the pathogen should lead to changes from initial broad-spectrum antimicrobial agents to more narrow-spectrum regimens to avoid the emergence of resistance. Unfortunately, positive cultures are infrequent in patients with nonpurulent cellulitis. Rapid expansion of the infected area, violaceous bullae or reddish-purple discoloration of the skin, severe pain, or systemic toxicity suggest necrotizing fasciitis, a condition that requires urgent surgical evaluation. CLINICAL BOTTOM LINE Treatment Which adjuvant measures are helpful in the treatment of patients with cellulitis and softtissue infection? Compression dressings in patients with chronic venous insufficiency or pedal edema promote resolution of cellulitis. Negative pressure dressings for large, exudative wounds reduce proteolytic enzymes and other substances that retard wound healing. Remediation of lymphedema or compromised vascular supply may improve delivery of oxygen and antimicrobials to the site of infection. There is insufficient evidence about the benefits of hyperbaric oxygen for infected diabetic foot ulcers and gas gangrene (23). 6 January 2009 Annals of Internal Medicine When is topical antimicrobial therapy appropriate? Topical mupirocin is an option for impetigo with limited lesions, but it is expensive and some staphylococci are resistant. Oral therapy with penicillinase-resistant penicillins or first-generation cephalosporins is preferred (16). How should clinicians determine whether to prescribe oral or parenteral antimicrobials? High bioavailability makes parenteral administration of antimicrobials largely unnecessary for mild, uncomplicated cellulitis. Parenteral therapy is usually reserved for moderate-to-severe infections that may require hospitalization. However, In the Clinic ITC1-7 22. Stevens DL, Bryant AE, Adams K, et al. Evaluation of therapy with hyperbaric oxygen for experimental infection with Clostridium perfringens. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;17:231-7. [PMID: 8399871] 23. Eron LJ, Lipsky BA, Low DE, et al. Expert panel on managing skin and soft tissue infections. Managing skin and soft tissue infections: expert panel recommendations on key decision points. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003;52 Suppl 1:i317. [PMID: 14662806] © 2008 American College of Physicians Oral Antimicrobials for Mild Infections Caused by Streptococci, MSSA, and MRSA Streptococci only • Phenoxymethyl penicillin • Amoxicillin Streptococci or MSSA • Amoxicillin–clavulanate • Cloxacillin, dicloxacillin, cephalexin • Clindamycin or a macrolide (if allergic to penicillins; and if sensitive) MSSA or MRSA • Clindamycin (if sensitive) • Doxycycline or minocycline • Trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole • Linezolid (very expensive) • Advanced fluoroquinolones– moxifloxacin and levofloxacin 24. Bergkvist PI, Sjöbeck K. Antibiotic and prednisolone therapy of erysipelas: a randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled study. Scand J Infect Dis. 1997;29:377-82. [PMID: 9360253] 25. Bergkvist PI, Sjöbeck K. Relapse of erysipelas following treatment with prednisolone or placebo in addition to antibiotics: a 1year follow-up. Scand J Infect Dis. 1998;30:206-7. [PMID: 9730318] 26. Dall L, Peterson S, Simmons T, et al. Rapid resolution of cellulitis in patients managed with combination antibiotic and anti-inflammatory therapy. Cutis. 2005;75:177-80. [PMID: 15839362] 27. Lee MC, Rios AM, Aten MF, et al. Management and outcome of children with skin and soft tissue abscesses caused by community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004;23:123-7. [PMID: 14872177] 28. Ruhe JJ, Menon A. Tetracyclines as an oral treatment option for patients with community onset skin and soft tissue infections caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:3298-303. [PMID: 17576834] © 2008 American College of Physicians parenteral agents may also be administered to outpatients if the patient is stable and has a social situation that enables out-patient therapy. Classification schemes have been proposed to assist in these treatment decisions (16, 23). In some patients, cutaneous inflammation worsens during the initial 24 hours of antimicrobial treatment. This is not necessarily a sign of treatment failure and may merely represent an inflammatory response to release of bacterial antigens. Anti-inflammatory agents may accelerate the resolution of the clinical signs of inflammation (2426). When patients do not improve when receiving what should be adequate antimicrobials, it could also represent antimicrobial resistance; a deeper, undrained collection; or complicating comorbid conditions. One study suggests that abscesses less than 5 cm in diameter may be effectively treated by incision and drainage without systemic antimicrobial therapy (27), but other studies show no correlation between the size of abscesses and the need for antibiotic therapy (28). treatment of MSSA include cloxacillin; dicloxacillin; cephalexin; and, for penicillin-allergic patients, clindamycin or a macrolide (erythromycin, clarithromycin, or azithromycin). However, patients treated with cephalexin should be observed for treatment failure, as some studies have reported high failure rates in adults (29), possibly due to poor absorption (30). Appropriate orally administered choices for the treatment of MRSA include trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole, doxycycline, minocycline, or linezolid. Linezolid is one of the few orally administered antimicrobials adequately tested in comparative trials with parenteral vancomycin. Clindamycin may be a very good alternative, if the S. aureus (MRSA or MSSA) is susceptible. However, resistance is becoming increasingly prevalent among S. aureus. Advanced fluoroquinolones, such as moxifloxacin and levofloxacin, may also be used, but only if patients cannot tolerate any other choices. Purulence is more often present in staphylococcal cellulitis. Specimens from wounds, carbuncles, or furuncles may reveal gram-positive cocci in clusters, consistent with S. aureus. Clinicians must judge whether MRSA or MSSA is likely. Appropriate choices for the oral Trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole is a reasonable initial choice for the treatment of mild, uncomplicated cellulitis. However, some experts feel that trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole should not be used for cellulitis without purulence because these drugs have relatively poor activity against streptococci (31). In one comparative trial, cures were obtained in 37 of 42 patients treated with orally administered trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole and 57 of 58 patients treated with vancomycin, suggesting equivalence between these 2 drugs in the treatment of mild cellulitis (32). A study comparing trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole with doxycycline suggested no statistically significant difference between these 2 antimicrobials in the treatment of cellulitis and soft-tissue infections caused by MRSA (33). The use of clindamycin and tetracyclines to treat ITC1-8 Annals of Internal Medicine In patients for whom oral therapy is appropriate, how should clinicians choose a specific antimicrobial agent? Generally, streptococci usually cause cellulitis without purulence. Phenoxymethyl penicillin, amoxicillin, or (for penicillin-allergic patients) clindamycin are all appropriate antibiotic choices (Box). However, a small number (<10%) of group A streptococci are resistant to clindamycin. In the Clinic 6 January 2009 MRSA is supported only by observational studies (34, 35). In patients for whom parenteral therapy is appropriate, how should clinicians choose a specific antimicrobial regimen? The choices for parenteral antibiotics for cellulitis probably caused by streptococci, as well as soft-tissue infection due to MSSA, include semisynthetic penicillins (nafcillin and oxacillin), cephalosporins (cefazolin, cefuroxime, or ceftriaxone), clindamycin (for penicillin-allergic patients and if the pathogen is shown to be sensitive). If MRSA is suspected, vancomycin, daptomycin, tigecycline, and linezolid are appropriate choices for moderate-to-severe infections. The newer agents have been shown to be noninferior to vancomycin in comparative trials. Some studies reported more rapid resolution of clinical signs of inflammation in patients receiving daptomycin compared with a matched cohort of patients receiving vancomycin (36, 37). For outpatient parenteral treatment of MRSA, daptomycin has certain advantages when compared with vancomycin. Daptomycin pharmacokinetics allow once-daily administration in patients with healthy renal function. Rapid administration does not cause “red-man syndrome” as Antimicrobials Commonly Used for Outpatient Parenteral Antibiotic Therapy • Ceftriaxone, cefazolin, and cefuroxime (for streptococci and MSSA infections) • Ertapenem, cefepime, ceftazidime (for gram-negative bacillary infection) • Daptomycin and vancomycin (for MRSA infections) • Clindamycin (for streptococci, MSSA, and MRSA infection, if sensitive) • Aminoglycosides (for resistant gram-negative bacillary infection) 6 January 2009 Annals of Internal Medicine happens with vancomycin, and it is not necessary to monitor daptomycin levels. A new antimicrobial agent, dalbavancin, is awaiting approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Its pharmacokinetics allow once-weekly administration, making it attractive for outpatient parenteral treatment. Dalbavancin has been compared with linezolid and shows similar efficacy (38) (Table 3). Other parenteral agents active against MRSA and pending release include telavancin, ceftobiprole, ceftaroline, and iclaprim. What is appropriate antimicrobial therapy for infections associated with human or animal bites? See Box for suggested antimicrobial treatment following bite wounds. The microorganisms involved in human bites are most commonly Eikenella corrodens, anaerobes, and viridans streptococci. Animal bites are commonly caused by a mixture of bacteria, including Pasteurella mutocida, Streptococcus intermedius, anaerobes, and S. aureus. A rare cause of infection following dog bites is Capnocytophaga canimorsus, which causes severe sepsis syndrome with disseminated intravascular coagulation but is susceptible to penicillins. Are there special considerations for antimicrobial selection in immunocompromised patients with cellulitis and soft-tissue infection? The clinical signs of infection in the immunocompromised patient may be subtle or absent due to decreased inflammatory response. Because of the extremely broad range of opportunistic pathogens in this patient population, attempts to definitively identify pathogens with cultures, biopsies, antigen tests, or imaging studies are crucial. Empirical therapy should be quickly initiated and guided by patient-specific clinical parameters and the most likely pathogens. For example, the most likely pathogens during the In the Clinic ITC1-9 Treatment of Human and Animal Bites Oral treatment • Human bite: amoxicillin/clavulanate • Animal bite: amoxicillin/clavulanate Parenteral treatment • Human bite: ampicillin/sulbactram • Animal bite: ampicillin/sulbactam Penicillin allergy • Human bite: moxifloxacin plus clindamycin, trimethoprim/ sulfamethoxazole plus metronidazole • Animal bite: doxycycline or moxifloxacin or trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole with either clindamyciin or metronidazole 29. Madaras-Kelly KJ, Arbogast R, Jue S. Increased therapeutic failure for cephalexin versus comparator antibiotics in the treatment of uncomplicated outpatient cellulitis. Pharmacotherapy. 2000;20:199-205. [PMID: 10678298] 30. Madaras-Kelly KJ, Remington RE, Oliphant CM, et al. Efficacy of oral betalactam versus nonbeta-lactam treatment of uncomplicated cellulitis. Am J Med. 2008;121:419-25. [PMID: 18456038] 31. Daum RS. Clinical practice. Skin and soft-tissue infections caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:38090. [PMID: 17652653] 32. Markowitz N, Quinn EL, Saravolatz LD. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole compared with vancomycin for the treatment of Staphylococcus aureus infection. Ann Intern Med. 1992;117:3908. [PMID: 1503330] 33. Cenizal MJ, Skiest D, Luber S, et al. Prospective randomized trial of empiric therapy with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole or doxycycline for outpatient skin and soft tissue infections in an area of high prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:2628-30. [PMID: 17502411] © 2008 American College of Physicians Table 3. Drug Treatment for Cellulitis and Soft-Tissue Infections Agent Dosage Side Effects Notes Low: 0.6–1.2 million IU/d, IM (benzathine); High: >20 million IU/d, IV (crystalline) Hypersensitivity Nafcillin 1.0–2.0 g, q4h IV or IM Oxacillin 1.0–2.0 g, q4h IV or IM Dicloxacillin 0.125–0.5 g, q6h PO Hypersensitivity; reversible neutropenia; interstitial nephritis; peripheral IV irritating Hypersensitivity; hepatic dysfunction with >12 g/d; interstitial nephritis Hypersensitivity Amoxicillin 0.5 g, q8h PO; 0.875 g, q12h Hypersensitivity Ampicillin 0.25–0.5 g, q6h PO; 150–200 mg/kg•per day, IV 1.0–3.0 g, q6–8h IV Hypersensitivity Benzathine useful only for impetigo due to Staphylococcus pyogenes or syphilis. Crystalline useful for mild-to-moderate streptococcal and clostridial infections and bite wounds Useful for staphylococcal infections except MRSA Useful for staphylococcal infections except MRSA Useful for minor infections with Staphylococcus except MRSA and Streptococcus Useful for Pasteurella and minor streptococcal infections Useful for Pasteurella and minor streptococcal infections Improved spectrum to Staphylococcus aureus and Bacteroides fragilis Excellent gram-negative spectrum, including Pseudomonas species ß-lactams Penicillin G Ampicillin– sulbactam Piperacillin– tazobactam Macrolides Erythromycin Hypersensitivity 2.25–4.5 g, q6h Hypersensitivity, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea; phlebitis when given IV; cholestatic hepatitis (erythromycin estolate) 0.5 g, q12h PO GI intolerance (4%); reversible dose-related hearing loss 0.5 g PO on day 1, then 0.25 GI intolerance (4%); reversible dose-related g/d PO on days 2–5; 0.5 g/d IV hearing loss Erythromycin resistance in S. aureus and group A streptococcus Cephalosporins Cefazolin 1.0–2.0 g, q8h IV or IM Hypersensitivity Cefuroxime 0.75–1.5 g, q6h IV or IM Hypersensitivity Cefoxitin Ceftriaxone Hypersensitivity Hypersensitivity; cholelithiasis Cefpodoxime Ceftobiprole 1.0 g, q8h; 2.0 g, q4h IV 0.5 g, q12h; 2.0 g, qd (total <4 g/d) IV or IM 100–200 mg, q12h PO 500 mg, q8h IV Useful for both staphylococcal and streptococcal infections More stable than cefazolin against Staphylococcus‚ ß-lactamase. Useful for staphylococcal and streptococcal infections. Reasonable activity against anaerobes Useful for outpatient prescription due to once-a-day dosing Ceftaroline 600 mg, q12h IV Clarithromycin Azithromycin Fluoroquinolones Ciprofloxacin 0.25–0.5 g, q6h PO; 15–20 mg/kg per day, IV 500–750 mg, bid PO; 200–400 mg, q12h IV Levofloxacin 500–750 mg, q24h IV or PO Moxifloxacin 400 mg, q24h PO Gatifloxacin 200–400 mg, q24h IV or PO Hypersensitivity Active against MRSA, VISA, VRSA, gramnegative bacilli Active against MRSA, VISA, VRSA, gramnegative bacilli CNS and GI disturbances; avoid caffeine; not for use during pregnancy and if age <18 y; Achilles tendon rupture CNS and GI disturbances; avoid caffeine; not for use during pregnancy and if age <18 y; Achilles tendon rupture CNS and GI disturbances; avoid caffeine; not for use during pregnancy and if age <18 y; Achilles tendon rupture Hypoglycemia; CNS and GI disturbances; avoid caffeine; not for use during pregnancy and if age <18 y; Achilles tendon rupture; rarely used due to toxicity risk Aminoglycosides (rarely used due to toxicity risk) Gentamicin 2 mg/kg load, then 1.5 mg/kg, Ototoxicity and nephrotoxicity q8h; 5.0 mg/kg (if critically ill, 7.0 mg/kg), q24h load © 2008 American College of Physicians ITC1-10 In the Clinic Excellent activity against gram-negative bacteria, including Pseudomonas Improved gram-positive spectrum against Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus species Improved gram-positive spectrum against S. aureus and Streptococcus species Improved gram-positive spectrum against Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus species. Contraindicated in diabetes. Use cautiously in the elderly and if renal insuffi ciency is present Good spectrum of activity against resistant gram-negative bacteria. Follow levels to guide dosing Annals of Internal Medicine 6 January 2009 Table 3. Drug Treatment for Cellulitis and Soft-Tissue Infections (continued) Agent Tobramycin Amikacin Glycopeptides Vancomycin Dalbavancin Lincosamides Clindamycin Tetracyclines Doxycycline Minocycline Tigecycline Dosage Side Effects Notes 2 mg/kg load, then 1.5 mg/kg, Ototoxicity and nephrotoxicity q8h; 5.0 mg/kg (if critically ill, 7.0 mg/kg), q24h load 15 mg/kg per day Good spectrum of activity against resistant gram-negative bacteria. Follow levels to guide dosing 15 mg/kg, q12h IV. Follow serum levels 1 g, IV followed 1 week later by 500 mg, IV Can cause nephrotoxicity and the “red-man” Used primarily against MRSA syndrome with rapid infusion. Active against MRSA, VRE (Van B and Van C strains only). Use for outpatient therapy once weekly 0.15–0.45 g, q6h PO; 1.2 g, IV q12h Pseudomembranous colitis Useful for severe group A streptococcal infections and gas gangrene caused by Clostridium species; inhibits bacterial toxin production; use for oral or dental infections 100 mg, bid Liver toxicity; photosensitivity; tooth discoloration in children 100 mg, qd or bid Dizziness 100 mg, IV load, 50 mg, q12h Nausea and vomiting IV thereafter Penems Imipenem–cilastatin 0.5–1.0 g, q6h IV Option for penicillin-allergic patients Active against MRSA, streptococci, anaerobic organisms, and gram-negative bacilli except Pseudomonas species Meropenem Doripenem 1–2 g, q6h IV 500 mg, q8h IV Superinfection; allergic reactions; phlebitis; hepatotoxicity; seizures; renal failure Diarrhea (5%); nausea, headache Headaches Broadly active against aerobes, anaerobes, gram-positives, and gram-negatives Ertapenem Oxazolidinone Linezolid 1 g, q24h Nausea, diarrhea, rash 2- to 4-fold lower MIC for Pseudomonas aeruginosa Use for outpatient therapy once daily 600 mg, q12h IV or PO Nausea, diarrhea, thrombocytopenia with prolonged treatment (>2 wk), peripheral neuropathy, optic neuritis Active against MRSA and VRE, but also against other gram-positive bacteria; should not be used when alternatives are available Lipopeptides Daptomycin 4–6 mg/kg per day Telavancin 7.5 mg/kg, q24h IV CPK elevation; rhabdomyolysis at high dosage Use for outpatient therapy once daily, use for bacteremia due to MRSA, as it is rapidly bactericidal Taste disturbance, headache Rapidly bactericidal with a long postantibiotic effect. Active against MRSA, GISA, VRSA, VRE (including Van A strains), may have a reduced potential for development of resistance bid = twice daily; CNS = central nervous system; DNA = deoxyribonucleic acid; GI = gastrointestinal; GISA = glycopeptide intermediate-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; IM = intramuscular; IV = intravenous; PO = oral; qd = once daily; MIC = minimal inhibitory concentration; MRSA = methicillinresistant Staphylococcus aureus; VISA = vancomycin intermediate-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; VRE = vancomycin-resistant enterococci; VRSA = vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. first week of postchemotherapy neutropenia are gram-positive organisms, such as staphylococci, viridans streptococci, enterococci, and grampositive bacilli, such as Corynebacterium, Clostridia, and Bacillus species. During the second week of neutropenia, antibiotic-resistant bacteria and fungi (Aspergillus, Candida, and Rhizopus and Mucor species) become prominent. Initial 6 January 2009 Annals of Internal Medicine antimicrobial therapy for cellulitis in immunocompromised patients should include coverage of both gram-positive and gram-negative microorganisms (ceftazidime, cefepime, piperacillin– tazobactam, meropenem, doripenem, or imipenem). Penicillinallergic patients should receive fluoroquinolones (such as ciprofloxacin) or aztreonam. In the Clinic ITC1-11 34. Martínez-Aguilar G, Hammerman WA, Mason EO Jr, et al. Clindamycin treatment of invasive infections caused by communityacquired, methicillinresistant and methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2003;22:593-8. [PMID: 12867833] © 2008 American College of Physicians Risk Factors for MRSA • Recent antibiotic use • Recent hospitalization • Recurrent needle sticks (IV drug use, hemodialysis, or insulinrequiring diabetic patients) • Homelessness, incarceration • Contact sports (football, wrestling) • Previous MRSA infection or colonization Indications for Hospitalization of Patients with Cellulitis and Soft Tissue Infections • Necrotizing fasciitis • Toxic shock syndrome or multiorgan failure • Limb-threatening infection • Need for surgical debridement or drainage • Gas in tissue • Inadequate home situation or patient at risk for nonadherence 35. Ruhe JJ, Monson T, Bradsher RW, et al. Use of long-acting tetracyclines for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections: case series and review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:1429-34. [PMID: 15844065] 36. Davis SL, McKinnon PS, Hall LM, et al. Daptomycin versus vancomycin for complicated skin and skin structure infections: clinical and economic outcomes. Pharmacotherapy. 2007;27:1611-8. [PMID: 18041881] 37. Krige JE, Lindfield K, Friedrich L, et al. Effectiveness and duration of daptomycin therapy in resolving clinical symptoms in the treatment of complicated skin and skin structure infections. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23:2147-56. [PMID: 17669231] © 2008 American College of Physicians Monotherapy of Pseudomonas infections seems at least equal to if not superior to dual therapy, in view of the toxicity associated with the addition of an aminoglycoside (39). Reasons for initiating aminoglycosides for empirical treatment include a high level of antimicrobial resistance within an institution. If patients remain febrile and cultures remain negative, the empirical addition of vancomycin or daptomycin for MRSA coverage and addition of amphotericin or an echinocandin (caspofungin, micafungin, or anidulafungin) or a triazole (voriconazole) are warranted for antifungal coverage. Patients with deficiencies of cell-mediated immunity (such as those with lymphoma, or HIV infection or organ transplant recipients) are beyond the scope of this article (16). When should clinicians consider coverage of MRSA when treating patients with cellulitis and softtissue infections? Although MRSA should be considered in all cases of cellulitis or soft-tissue infection (because of its widespread prevalence), particular populations are at higher risk than others (see Box). MRSA and MSSA should be suspected in patients with purulent cellulitis, although streptococci can also cause purulent cellulitis. When should clinicians hospitalize a patient with cellulitis and softtissue infection? Mild, uncomplicated cellulitis may be treated out of the hospital with oral antibiotics. Although surgical drainage may be required in some cases, this can also be done on an outpatient basis. Moderate-tosevere cellulitis, however, may require hospitalization for observation, control of comorbid conditions, and administration of parenteral antimicrobial agents. ITC1-12 In the Clinic Because necrotizing fasciitis is associated with shock and organ failure, with a mortality rate ranging from 30% to 70% (16), these patients require hospitalization for surgical debridement, prompt antibiotic treatment, and monitoring. When the diagnosis is in doubt, in-hospital observation is appropriate until the clinical course becomes clear. See Box for conditions that may require hospitalization. Generally, hospitalized patients with cellulitis or soft-tissue infection can be discharged when no longer febrile, when the cellulitis is no longer spreading, and when the leukocyte count is trending toward normal. When should clinicians consider consulting infectious disease experts? Involvement of an infectious disease expert may result in more appropriate and cost-effective use of antimicrobial agents and may be helpful when patients are immunocompromised, have severe infection, or do not improve on initial therapy. In one study, more-appropriate treatment was ordered initially by a consulting infectious disease specialist (78%) than without such consultation (54%). Following the availability of culture results, appropriate treatment increased to 97% and 89%, respectively (40). What should clinicians consider in managing patients with necrotizing fasciitis? Type 1 necrotizing fasciitis is usually a polymicrobial infection due to S. aureus, group B streptococci, anaerobic organisms, and gramnegative bacilli. Management includes broad-spectrum antimicrobials, surgical debridement, vascular evaluation, off-weighting of the lower extremity, and normalization of blood glucose levels. Type 2 necrotizing fasciitis is known colloquially as “flesh-eating strep,” because it is caused most frequently Annals of Internal Medicine 6 January 2009 by streptococci. Occasionally, staphylococci and gram-negative bacilli, such as Vibrio vulnificus, are isolated from necrotizing soft-tissue infections. For streptococcal necrotizing fasciitis, the antimicrobial agent of choice is clindamycin combined with penicillin or other β-lactam antibiotic. As 5% of streptococci are resistant to clindamycin, penicillin is added to clindamycin in case of resistance (16). Linezolid is an expensive but appropriate choice for staphylococcal necrotizing fasciitis in penicillinallergic patients (16). However, in cases of intolerance to linezolid, daptomycin is an option. Type 3 necrotizing fasciitis is characterized by severe toxicity and gas in tissues due to infection with clostridial species. Penicillin plus clindamycin with debridement is the therapy of choice (16). What are the indications for surgical debridement of cellulitis and soft-tissue infection? Evidence of gangrenous or necrotizing infection requires immediate and thorough debridement. This is especially true of streptococcal necrotizing fasciitis. Expert consensus favors the use of intravenous immunoglobulin to treat streptococcal necrotizing fasciitis, although studies are conflicting (41-43). Friable fascia and dark muscle that do not bleed or twitch requires debridement, which should be continued until viable tissue is reached. Multiple debridements are often required for patients with necrotizing fasciitis or myonecrosis. Delay of surgical debridement increases mortality. How long should patients remain on antimicrobial therapy for cellulitis and soft-tissue infection? When treating moderate-to-severe cellulitis, it is appropriate to switch from parenteral to oral antibiotics when the infection is stabilized and the patient is able to tolerate oral therapy. Many antimicrobials exhibit complete oral bioavailability and comparative trials have shown the equivalence between parenteral and orally administered antimicrobials in the treatment of soft-tissue infections (44, 45). There may be no advantage in administering parenteral antibiotics in patients who have infections susceptible to oral therapies and no symptoms, such as nausea and vomiting, that would complicate oral therapy. Patients with cellulitis and softtissue infection often receive antimicrobial therapy for 10 to 14 days or until inflammation resolves. This practice assumes that inflammation indicates surviving organisms, but after several days of antimicrobials, inflammation may be due to antigens released from dead bacteria. Clinical trial evidence shows similar outcomes in patients treated for 5 days and 10 days (46). Treatment... Treat cellulitis and soft-tissue infections empirically with antimicrobials that target the suspected pathogen. Topical treatment is an option for mild impetigo. Patients with mild, uncomplicated cellulitis who are not at high risk for MRSA should receive oral antibiotics active against both staphylococci and streptococci. Abscesses require drainage. Oral antibiotics are sufficient to treat mild MRSA infection. Patients unable to tolerate oral antibiotics or those with severe cellulitis and systemic toxicity who are at risk for MRSA should receive parenteral antibiotics active against MRSA and streptococci. Patients at risk for MRSA should receive coverage for MRSA and streptococci. Antimicrobials should be adjusted to focus on culture-identified pathogens. Prompt surgical evaluation is indicated for patients with evidence of necrotizing fasciitis. CLINICAL BOTTOM LINE 6 January 2009 Annals of Internal Medicine In the Clinic ITC1-13 38. Billeter M, Zervos MJ, Chen AY, et al. Dalbavancin: a novel once-weekly lipoglycopeptide antibiotic. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:577-83. [PMID: 18199045] 39. Paul M, Silbiger I, Grozinsky S, et al. Beta lactam antibiotic monotherapy versus beta lactamaminoglycoside antibiotic combination therapy for sepsis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006:CD003344. [PMID: 16437452] 40. Byl B, Clevenbergh P, Jacobs F, et al. Impact of infectious diseases specialists and microbiological data on the appropriateness of antimicrobial therapy for bacteremia. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:60-6; discussion 67-8. [PMID: 10433566] 41. Stevens DL. Dilemmas in the treatment of invasive Streptococcus pyogenes infections [Editorial]. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:341-3. [PMID: 12884157] 42. Kaul R, McGeer A, Norrby-Teglund A, et al. Intravenous immunoglobulin therapy for streptococcal toxic shock syndrome—-a comparative observational study. The Canadian Streptococcal Study Group. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;28:800-7. [PMID: 10825042] 43. Darenberg J, Ihendyane N, Sjölin J, et al. StreptIg Study Group. Intravenous immunoglobulin G therapy in streptococcal toxic shock syndrome: a European randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:333-40. [PMID: 12884156] 44.Gentry LO, RamirezRonda CH, Rodriguez-Noriega E, et al. Oral ciprofloxacin vs parenteral cefotaxime in the treatment of difficult skin and skin structure infections. A multicenter trial. Arch Intern Med. 1989;149:257983. [PMID: 2684078] © 2008 American College of Physicians 45. Weigelt J, Itani K, Stevens D, et.al. Linezolid versus vancomycin in treatment of complicated skin and soft tissue infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:2260-6. [PMID: 15917519] 46. Hepburn MJ. Dooley DP, Skidmore PJ, et. Al Comparison of short course (5 days) and standard (10 days) treatment for uncomplicated cellulitis. Arch Intern Med. 2004; 164:1669-74. [PMID: 15302637]). What factors do U.S. stakeholders use to evaluate the quality of care for soft-tissue infection and cellulitis? The Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has developed measures of quality of care to use in the Physician Quality Reporting Initiative. None of these measures relates to the treatment of cellulitis and soft-tissue infection. However, several measures focus on the antibiotic prophylaxis to prevent surgical wound infections. These measures focus on the appropriate timing and selection of antibiotic prophylaxis (started within 1 hour [2 hours for fluoroquinolone or vancomycin] before surgical incision and discontinued within 24 hours of the end of surgery). What do professional organizations recommend regarding the care of patients with cellulitis and soft-tissue infection? In 2005, the Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA) released guidelines on the management of cellulitis and soft-tissue infection (16). This review largely reflects the IDSA recommendations. See the Toolkit for other guidelines related to the prevention and treatment of soft-tissue infections. PIER Modules in the clinic Tool Kit Cellulitis and Soft-Tissue Infections www.pier.acponline.org Access the following PIER module: Cellulitis and Soft Tissue Infections. PIER modules provide evidence-based, updated information on prevention, diagnosis, and treatment in an electronic format designed for rapid access at the point of care. Patient Education Resources www.annals.org/intheclinic/toolkit-cellulitis.html Access the Patient Information material that appears on the following page for duplication and distribution to patients. www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/cellulitis.html Medline Plus www3.niaid.nih.gov/topics/streptococcal/ National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases www.healthsystem.virginia.edu/uvahealth/adult_derm/cell.cfm Patient information developed at University of Virginia (available in English and Spanish). Guidelines www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/pdf/10.1086/497143 Infectious Diseases Society of America: Practice Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Skin and Soft Tissue Infections www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dhqp/pdf/ar/mdroGuideline2006.pdf Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Guidelines for the Management of Multi-drug Resistant Organisms in Healthcare Settings www.shea-online.org/Assets/files/position_papers/SHEA_hand.pdf Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee and the HICPAC/SHEA/APIC/IDSA Hand Hygiene Task Force: Guideline for Hand Hygiene in Healthcare Settings www.shea-online.org/Assets/files/position_papers/SHEA_MRSA_VRE.pdf Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America © 2008 American College of Physicians ITC1-14 In the Clinic in the clinic Practice Improvement Annals of Internal Medicine 6 January 2009 In the Clinic Annals of Internal Medicine annals.org THINGS PEOPLE SHOULD KNOW ABOUT CELLULITIS AND SOFT-TISSUE INFECTION What is cellultis? • Cellulitis is an infection that involves the skin or the muscles and other body tissues directly under the skin. Symptoms can include redness, pain, and fever. Who gets cellulitis? • Cellulitis can happen after an injury to the skin, an animal bite, or a surgical wound, but sometimes there is no obvious cause. • Conditions that increase the chances of cellulitis include diabetes, circulatory problems, past surgery or radiation treatment of the arms or legs, and chronic athlete’s foot. What is the treatment for cellulitis? • Patients with diabetes should talk to their doctors about proper foot care to prevent infection. • Keep skin moisturized to prevent cracks. • Treatment usually involves cleaning the injury or wound, if present, and antibiotics. • If you have athlete’s foot, treat it. • If the infection is severe, then hospitalization for intravenous antibiotics may be necessary. Cellulitis can be an emergency. See a doctor if you notice: • Sometimes surgery is needed to clean and drain the infected area. • a very large area of red, inflamed skin • Look out for early signs of infection. • Clean any skin injuries very well. • See a doctor if you have an animal bite. • affected area of skin is numb, tingling, or in severe pain • skin seems black, purple, or has blisters • redness or swelling around the eye(s) or behind the ear(s). For More Information Medline Plus www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/cellulitis.html National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases www3.niaid.nih.gov/topics/streptococcal/ University of Virginia (information in English and Spanish) www.healthsystem.virginia.edu/uvahealth/adult_derm/cell.cfm Patient Information Can you prevent cellulitis? • fever CME Questions 1. A 20-year-old college wrestler has a 3. An 83-year-old woman is brought to the emergency department physician prescribed warm packs to the area and a painful lesion on his upper back. He first emergency department with redness and course of dicloxacillin. The patient noted a small painful area 7 days ago, swelling of her right lower leg of several returns to the emergency department 2 and the lesion has since enlarged and days’ duration and a 12-hour history of days later. The patch is larger and more became more red. Other members of his nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. The tender but is still not fluctuant. He is wrestling team have developed similar patient has type 2 diabetes mellitus and slightly ill but does not seem toxic. The lesions. His history is otherwise coronary artery disease. Medications emergency department physician uneventful. Examination of the upper include glyburide, an angiotensin-conchanges the antibiotic to cephalexin, back reveals a 1 × 1 cm2 red, raised pusverting enzyme inhibitor; a β-blocker; a but the patient continues to become statin; and low-dose aspirin. tule that is tender to palpation, with a 4 somewhat worse over the next 2 days. × 4 cm2 area of surrounding erythema. On physical examination, temperature is The remainder of the physical examinaWhich of the following is the most 38.9°C (102°F), pulse rate is 102/min, tion is normal. The lesion is incised, likely cause of this patient’s clinical respiration rate is 20/min, and blood drained, and cultured. deterioration? pressure is 92/64 mm Hg. Profuse crackles are heard at both lung bases. Cardiac Which of the following is the most A. Lyme disease examination discloses a regular rhythm appropriate empiric treatment? B. An abscess and no audible murmurs; there is a A. Levofloxacin C. Fasciitis prominent S3. The right leg is more B. Doxycycline D. A β-lactam–resistant organism swollen than the left and is erythemaC. Dicloxacillin tous with tenderness to the knee. There 5. A 53-year-old man underwent open D. Cephalexin are no open lesions, and no inguinal reduction and internal fixation of a lymphadenopathy is noted. Hemoglobin 2. A 32-year-old man has a 1-week history fractured tibia. The patient has diabetes level is 11.4 g/dL (114 g/L); hematocrit is mellitus and end-stage renal disease of worsening erythema and pruritus 34%; leukocyte count is 19.8 × 109/L and requires hemodialysis by means of of both axillae. He is otherwise with 80% neutrophils, 15% lymphoan arteriovenous graft in the left-upper asymptomatic. cytes, and 5% monocytes; platelet count extremity. Three weeks postoperatively, On physical examination, temperature is is 281 × 109/L; blood urea nitrogen is 34 his surgical incision became inflamed, 37.1ϒC (98.8ϒF), pulse rate is 72/min, mg/dL (12.14 mmol/L); serum creatinine with an open section and drainage of respiration rate is 16/min, and blood level is 2.2 mg/dL (194.52 µmol/L); and cloudy yellow fluid. Culture of the dispressure level is 128/62 mm Hg. Both serum electrolytes and liver chemisty charge grew methicillin-resistant axillae show marked erythema, minimal studies are normal. Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) that was tenderness, and several small nonpusturesistant to erythromycin, clindamycin, The patient is hospitalized. Blood cullar vesicles. There is no erythema adjaand tetracycline but was sensitive to tures obtained on admission show no cent to the axillae and no palpable lymvancomycin and trimethoprim– growth at 2 days. phadenopathy. Hemoglobin level is 15 sulfamethoxazole. The patient was g/dL (150 g/L); hematocrit is 47%; Which of the following organisms is treated intermittently with vancomycin, leukocyte count is 5.3 ↔ 109/L with most likely causing this patient’s current 500 mg intravenously. Two months later, 72% neutrophils, 18% lymphocytes, 2% findings? the surgical incision is unchanged. Culmonocytes, 8% eosinophils; and platelet A. Escherichia coli ture of the discharge now grows Enterocount is 310 × 109/L. Cultures of the B. Clostridium tetani coccus faecalis in addition to MRSA. axillae grow several coagulase-negative C. Staphylococcus aureus Both pathogens are resistant to vanstaphylococci, Propionibacterium acnes, D. Bacillus cereus comycin. Polymerase chain reaction and rare Escherichia coli. shows that the MRSA is vanA ligase– 4. An 18-year-old male basketball player Which diagnosis is most likely? positive. came to the emergency department in A. Streptococcal cellulitis Which of the following is the most February because of a red patch on his B. Staphylococcal cellulitis appropriate antibiotic agent? left forearm. He had been well the day C. Pasteurella multocida cellulitis before, but woke up with a painful area A. Linezolid D. Contact dermatitis 2 measuring about 6 ↔ 9 cm on the B. Trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole E. Hidradenitis suppurativa volar surface of the forearm. The area C. Clindamycin was tender to touch, erythematous, D. Imipenem and raised but was not fluctuant. The E. Quinupristin–dalfopristin Questions are largely from the ACP’s Medical Knowledge Self-Assessment Program (MKSAP). Go to www.annals.org/intheclinic/ to obtain up to 1.5 CME credits, to view explanations for correct answers, or to purchase the complete MKSAP program. © 2008 American College of Physicians ITC1-16 In the Clinic Annals of Internal Medicine 6 January 2009

© Copyright 2026