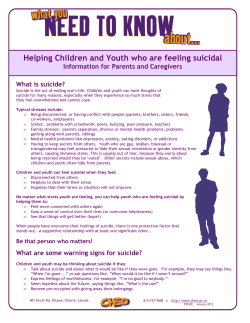

Document 144943