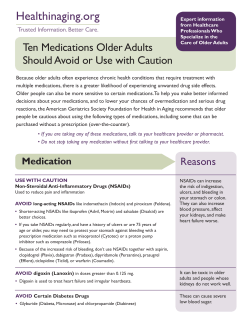

Getting Started with Medication-assisted Treatment With lessons from Advancing Recovery TM