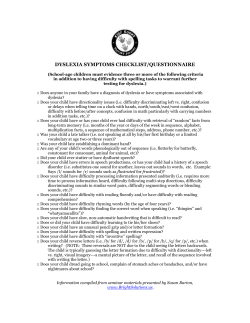

Living with Dyslexia Information for Adults with Dyslexia