The Casino of Crime Films

!

!

!

!

The Casino of Crime Films: Glamor and Demonization

!

!

!

!

!

!

!

!

!

!

!

!

!

!

!

!

!

!

!

!

!

!

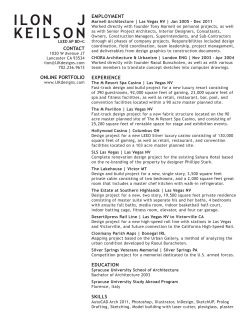

Selected Topics in Film Studies: Crime Genres

Dan Babineau

!

!

Matthew Dessner

!

!

!

!

November 25, 2014

The Casino of Crime Films: Glamor and Demonization

“I hate Disneyland. It primes our kids for Las Vegas.”

- Tom Waits (“Tom Waits Biography” - IMDB)

Since childhood, we have been commodified into dream-seekers. Companies like Disney

profit in producing aspiring superheroes and princesses, promoting dreams as attainable

commodities to every boy and girl; their slogan, “where dreams come true” perfectly

encapsulates this notion ("Disney Parks | Where Dreams Come True."). Las Vegas is no different;

Robert De Niro illustrates how “running a casino… is like selling people’s dreams for cash” in

his opening monologue as Ace Rothstein in Scorcese’s 1995 masterpiece, Casino. The city of

lights turns its guests into commodified dogs on a leash, gnawing at an unattainable dream of

winning big, of being big and of living big; these dream seekers, try as they might, will never be

free of the leash which restricts them from doing so and thusly, Ace clarifies, “the truth about Las

Vegas… we’re the only winners [and] the players don't stand a chance”. While gambling has

been around for millennia, the casino’s commodification into a space where dreams are bought

and sold is but a constructed capitalist mentality propagated by the media’s portrayal. Frankfurt

school theorists, Adorno & Horkheimer, expand upon a Marxist critique explaining how in the

culture industry products are judged upon their extrinsic economic value; thus the “triumph of

invested capital” is of utmost importance, while the superficial elements are worthless, existing

only to keep a society entertained (99). After removing the glitter, the luxurious venues, the welldressed croupiers, the scantily-clad women, thus de-fetishizing the conspicuous elements of the

casino commodity, what remains is a space designed to collect an unprecedented amount of

profit. Any discussion regarding the media’s representation of the casino must then focus upon

1

the epicentre of the gambling world and its superficialities, Las Vegas. Films undoubtably

contribute to the unending refinement of the ideological discourses which provide meaning to the

casino and the world-wide gambling mecca. Moreover, the crime genre in particular has a

uniquely thought-provoking narrative potential, because it proposes a socio-cultural questioning

of the ethics behind gambling and casino culture. Many addicts will admit that while they simply

enjoy gambling, their goal is always to outplay the house; therefore, in perceiving the casino as

an adversarial force, we are fascinated by the crime film which tells the story of a person or

group successfully “beating” the casino or winning a large sum of money. It thus becomes a

battle between the unlawful casinos, often backed by mafia related groups who will go to any

and every means to make sure they don't lose capital, and the players who will often use

unlawful methods or tricks that have been frowned upon to gain an upper hand. To summarize,

this analysis will consider a select group of crime films which best develop an ideological

discourse characterizing casino culture in order to better understand the intrinsic allure of Las

Vegas, the casino, of gambling and of the gamblers; furthermore, I hypothesize that while the

discourses perpetuated by these films create a false consciousness wherein our wildest dreams

come true, they concurrently demonize the forces which would prevent these dreams from being

realized in actuality.

In order to develop my analysis I looked at several films including: Casino, The Good

Thief, Ocean’s Eleven (2001), Casino Royale (2006), Rounders, 21, God of Gamblers, Bob le

Flambeur, Hard Eight, Tazza: The High Rollers and The Cooler. The films had all been released

in theatres and received above 6.5 on IMDB. Numerous films were made outside of the United

States which adds a limited but relevant international significance to my analysis. Finally, I

2

tended to gravitate towards Martin Scorcese’s Casino because it best epitomizes many of the

discourses present in all of the considered films.

Even if one has never gotten the chance to attend a casino, they would likely already hold

a certain set of expectations due to its portrayal in the media: neon lights are flashing, people are

dressed up and looking beautiful while money is being thrown around like candy. Aesthetically,

every casino in the world seems to look up to the big casinos which dominate a part of Las Vegas

that has been nicknamed The Strip. Many of the films I analyzed either perpetuated this ideal

casino aesthetic or alluded to it, glorifying the high-stakes world of gambling and making it seem

ever so attractive. In Scorcese’s Casino, the Tangiers is aesthetically beautiful, however, its

glamour is not achieved so much in flashy looks but in the film’s narrative. Ace Rothstein will

only accept the best at his Casino; for instance, when a croupier doesn't stack his chips properly,

Ace threatens to fire him, and when a certain dancer doesn’t meet her weight requirement he

forces the choreographer to get rid of her. In other films, the ideal casino aesthetic is displayed

visually; for example, in Robert Luketic’s 21, Steven Soderbergh’s Ocean’s Eleven, and Neil

Jordan’s The Good Thief, the casinos are all grandiose, beautiful and flashy - just as the spectator

expects them to be. Grand staircases, million dollar paintings and arched ceilings are just

examples of what might be found within the Monte Carlo casino displayed in The Good Thief. In

21, we are introduced to Las Vegas and casino culture with an aesthetically gripping sequence

that tours down The Strip and bombards the spectator with the lights and sounds of the city of

sin. Towards the end of Ocean’s Eleven the glory of the casino is so strongly symbolized when a

boisterous audience is attending the establishment’s boxing match; its presence becomes dually

important because it also displays a symbolic onlooking of the $160 million dollar heist which is

3

simultaneously taking place. As it boils down, the situation is akin to some sort of gladiatorial

combat with Ocean’s beloved gang of thieves representing the challengers and Terry Benedict,

the billionaire owner as the champion who will be dethroned while a barbaric audience is

watching.

The idealized image of the casino is further promoted by its underbelly - a somewhat

dark and grimy divergent space often depicted as a training area of sorts. It should be noted that

this place differs in narrative objective across any certain set of casino-related films, however, it

always provides a stark contrast when placed beside the idealized casino. In Ocean’s Eleven,

Daniel Ocean’s adept cunning is displayed early on in the film when he out bluffs a group of

friends and wins a large sum from a poker hand. This scene takes place in a suspicious space

within the back room of a club where the only things illuminated are the actors faces at the poker

table and the erotic dancers in the background. This is then contrasted against the golden interior

of the casino depicted towards the end of the film. This effect provides a symbolic rags to riches

and the heist narrative further supports that suggestion. In John Dahl’s Rounders, Mike

McDermott and Worm are obsessive gamblers who spend much of their time in shady bars and

private spaces playing high stakes poker against some threatening opponents. Up until the final

scene it seems as if the biggest stage for McDermott is in the basement of a Russian mob boss;

however, as the film’s conclusion suggests, the whole movie was just a preparation for his

hopeful attendance at the televised world series games - the biggest stage in poker. In Casino, the

mob bosses which immorally govern Las Vegas from their hideout in Kansas City are often seen

dining, conversing and playing cards behind closed doors at a local Italian grocery. In their book,

Casino State, James F. Cosgrave and Thomas R. Klassen discuss this “back room’ phenomenon

4

stating that “informal card games with money stakes taking place in back rooms of commercial

premises, attracting local businessmen, municipal officials, and farmers, were seen as innocuous

by some and embarrassments by others” (33). For governments, there is a desire to regulate back

room gambling, bringing all high-stakes action to the casinos where it can be properly taxed.

Cosgrave and Klassen continue, mentioning how over the last 80 years, “the move into casinos,

video lottery terminals, and sports betting is a response to developments and competition where

ongoing liberalization creates market pressures, and where jurisdictions are in competition for

gambling dollars” (49). These political developments have clearly become accepted socially and

throughout the media. The glamorous, fast-paced casino has been depicted in films, which in

turn, causes its antithesis - the back room gambling space, to carry negative connotations.

Therefore, a circle is created wherein earlier media representations of the idealized casino

contributed to the development of a discourse with a certain set of ideologies; sequentially,

newer films will follow and develop upon said discourse. Thus, the casino and, particularly, the

major Las Vegas establishments have become and will likely remain the biggest stages for the

characters in crime films to occupy - professional gamblers, heist crews, mafiosos, businessmen their lives will eventually lead them to Vegas or to somewhere relatively comparable.

To conduct an analysis of this type, one would be foolish to not acknowledge the

personalities of the characters at play. The animated opening sequence of Martin Campbell’s

2006 Bond film, Casino Royale, beautifully illustrates and typifies many tropes and character

tendencies of the style. Set to Chris Cornell and David Arnold’s “You Know My Name”, the

sequence exhibits endless imagery affiliated with a deck of playing cards. For instance,

characters are shot with bullets in the shape of spades, they bleed diamonds, jacks fire at the

5

Bond silhouette, while the queen is watching over the action. Everything becomes afflicted with

gambling-related symbolism; throughout the film this grows in meaning and fully represents the

characteristics of greed and fame. The imagery continues as enemy silhouettes are being killed

by Bond, exploding in to hearts and spilled across the screen. Meanwhile, Cornell sings “the

coldest blood runs through my veins, you know my name” - a line that would fit quite well

within the scripts of any casino-related crime film. Ocean’s Eleven intriguingly concludes with

the words, “liar” and “thief”; while the words are directed towards the main characters, it

provides further understanding to symbolically attribute them to the casino management as well.

Throughout the film the spectator is unfailingly supportive of the heist, hoping that Ocean’s

eleven men get away with the crime. As collective dream seekers, with an adversarial view

towards the casino we see the management as criminals themselves, lying and stealing money

from citizens while making the whole operation seem legal. Casino management, security,

gamblers and thieves alike must all be cold blooded to some extent when working in an

inherently unethical field. For this reason, many protagonists expressed a particular reluctancy

upon entering the gambling business. For instance, in Casino, Ace is persuaded after a long

discussion with one of the mob bosses, while in 21, card counter Ben is convinced into the artful

operation by his teacher and love interest. There is a symbolic innocence that is lost when

characters go from an honest career path to a lifestyle of gambling and money-driven work. The

radical of which is impeccably alluded to in Rounders, where we see McDermott transform from

a model law student into a marked man, gambling for his life.

There are other tropes which seem to be often associated with casino-related crime films.

Apart from the characteristics of greed and fame, characters frequently struggle with the ability

6

to trust another person. Indeed, trust is hard to come by in films where the amassing of capital

takes centre stage. In Casino, Ace rightfully struggles to trust his troubled wife as she

continuously acts disloyal to him. Likewise, he and his psychopathic childhood friend, Nicky

share an unwavering trust despite their growing annoyance towards each other - and even at the

climax of the film Nicky refuses to kill Ace when given the opportunity. In Ocean’s Eleven and

21 the characters are forced to display an immeasurable amount of trust in one another because

their respective heist operations and card counting assignments require all members to be on the

same page. At a certain point in Ocean’s Eleven when Daniel is holding a secret, members of the

group survey him to assess if he is trustworthy. Trust, or, the lack thereof is a notion fully linked

to the casino. When at a poker table, even with friends, one must, as instructed by Daniel’s best

friend Rusty, “leave emotion at the door”. The importance of trust is addressed in quite the

forthright manner by a crooked stockbroker in Casino Royale who before killing his business

partner declares that “money isn’t as valuable to our organization as knowing who to trust”.

Surveillance and security often play a major role. In nearly every film, security was an

oppressive force; as such, it tended to take an adversarial role much like the casino itself,

becoming a major obstacle to the happy ending of the narrative. In a heist film like Ocean’s

Eleven or The Good Thief, it is a primary obstacle to the thieves’ end goal. In both films, tactics

were put in motion to bypass security systems and guards. One tactic used in both stories

required a certain technologically adept character to hack the casino surveillance systems,

allowing the thieves to broadcast a fake signal while the vault was being broken into. We

sympathize with the thieves because casino security is often seen as greedy, using unlawful

methods to ensure that owners never lose significant amounts of capital; this fully goes against

7

the spectators desired dream seeking narrative. This can manifest in violent action; for instance,

in Casino, and 21 security beats its casino-goers to a pulp if they so dare to try anything

suspicious. In Paul Thomas Anderson’s Hard Eight, Jimmy, a casino security guard becomes the

primary threat to the calm and composed Sydney who struggles to deal with his shameful past.

Moreover, the surveillance cameras take a life of their own. In Ace’s opening monologue of

Casino, he mentions that while everybody involved in the casino hierarchy is observing the

actions of those below themselves, making sure that nobody steps out of line, Ace states that “the

eye in the sky is watching us all”. No one is free from surveillance.

Such an oppressive system often requires a touch of fantastical intervention for one to be

triumphant. There’s a reason that the narrative of Ocean’s Eleven would never happen in real life

- its essentially impossible. The unbelievably impeccable timing of the heist down to the last

second, the fact that the heist team stole and set off a pinch (electromagnetic bomb that was used

to disrupt the city’s power supply) from the back of a van without being caught or having the

amount of power that would be necessary to do so - this supernatural intervention of sorts is

obviously geared towards the spectators entertainment. However, some of the films made these

supernatural occurrences quite conspicuous. For instance, in Wong Jing’s God of Gamblers, Ko

Chun discovers his superhuman gambling abilities which allow him to win every single bet he

makes. Similarly, at the end of The Good Thief, Bob Montagnet, a gambler who had been

afflicted with quite the losing streak has his fortunes reversed in quite the supernatural fashion.

After already having won numerous hands, on a bet worth millions of dollars, Bob is dealt a 10 ace straight, forcing the casino to cut his night short. The fantastical narrative of the film is also

symbolized by the films imaginative editing which uses freeze-frames among other editorial

8

techniques to make the viewer aware that they are indeed watching a film and the narrative is not

equal to reality.

By the end of Rounders, Mike McDermott is convinced that the only place on earth

where he feels alive is at the poker table. Rightfully, the film ends with him beginning his

journey to Vegas. Similarly, in God of Gamblers, Ko Chun plans to leave Hong Kong and use his

supernatural powers in Vegas. Indeed, all roads lead to Las Vegas. In 21 Ben’s love interest tells

him that “the best thing about Vegas is you can become anyone you want”. This mentality is

obviously shared by many characters. In Casino Nicky describes the city as “untouched”. In this

way, Las Vegas becomes like the wild west - an interesting comparison when one contemplates

the history of American Colonialism. At a certain point in the same film the county

commissioner warns Ace that “your people will never understand the way it works out here you’re all just our guests but you act like you’re at home”. This statement holds a great amount

of meaning; while professional gamblers, heist crews, mafiosos and businessmen all flock to

Vegas, the locals - people who actually live in the state of Nevada are somewhat forgotten and

pushed aside. These individuals often work in the casino as dealers, cooks, maids and janitors but

their stories are completely forgotten or simply ignored by the media (Miller 7). If we further

contextualize this statement, we can dig deep into the history of American Colonialism and see

that even those who settled in and around Las Vegas further displaced the Indians upon their

arrival in the mid-1800s (Warren and Mooney). In this way, Casino becomes imbued with

meaning, motivating us to question the capitalist nature of society at its roots.

Ultimately, in considering the casino as symbolized discourse of capitalism, many aspects of

casino and gambling culture identify with this comparison. The average citizen is always looking

9

out for themselves; they’ll do anything to make an extra buck. They work honest, alienating jobs

and dream of winning big money so they can escape the “forces of production” (Borchert 732).

Meanwhile, the leaders of society set rules into place - or casino games; the games do not have

fair odds and the leaders ensure that they stay profitable. However, in reality, the leaders are just

figureheads of sorts, and they are being told what to do by another certain set of insanely wealthy

people - in Marxist terms, the “relations of production” (Borchert 732). Furthermore, we are

constantly being surveyed to make sure that we don’t step out of line. Evidently, everything

revolves around money. Capitalism is so engrained in our minds that we negotiate with it in our

dreams, perceiving a city like Las Vegas as the place where dreams are made. The casino of

crime films is so attractive because the we hunger to believe in chance and luck, because only

with good fortune might we be able to escape the monotony of the work day. Adorno and

Horkheimer describe chance in a capitalist society distinguishing that it “itself is planned, not

because it affects any particular individual but precisely because it is believed to play a vital part.

It serves the planners as an alibi, and makes it seem that the complex of transactions and

measures into which life has been transformed leaves scope for spontaneous and direct relations

between man” (117). The average winner at a casino will not threaten the owner, and in fact, a

winner is necessary for citizens to continue going to the casino. The odd winner will not escape

capitalism, because they cannot escape its circular embrace; even after winning a big hand, said

individual might buy everyone a round of drinks, throwing the money back into the system

which confines them so.

Characterizing Las Vegas as a city where dreams come true is thusly a false

consciousness fully supported by the films in this analysis; however, we are fully aware of the

10

casino’s magnetic appeal which is why we further demonize it and doubt the ethical practices of

those who are in charge. Either way, there is a definitive aura surrounding the Vegas portrayed in

these films. A thought-provoking conclusion to Scorcese’s Casino documents how after Ace left

the business, many of the older casino establishments with mafia affiliations were being

demolished and replaced with commercialized, mass-produced nonsense. In these brand new

casinos customer service disappeared; Ace discusses how today, a visit to Vegas is “like checking

into an airport, and if you order room service, you’re lucky if you get it by Thursday”. This

assessment directly coincides with Adorno & Horkheimer’s concept of a culture industry

wherein the superficialities of the casino are completely unimportant; mass production has taken

every product and made it identical (95), and in consequence, the discourses which embody the

Vegas casino lose some of their prior meaning. Therefore I ask, will this city still be as relevant

in the future? Furthermore, will the casino heist or the gamblers narrative continue to arouse the

film viewer? - I wouldn’t bet on it.

!

!

!

!

!

!

!

!

!

11

Works Cited

!

21. Dir. Robert Luketic. Columbia Pictures, 2008.

Bob Le Flambeur. Dir. Jean-Pierre Melville. 1956.

Borchert, Donald M. "Karl Marx." Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Detroit, MI: Thomson Gale/

Macmillan Reference USA, 2006. 730-35. Print.

Casino. Dir. Martin Scorsese. Universal Pictures, 1995.

Casino Royale. Dir. Martin Campbell. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer / Columbia Pictures, 2006.

The Cooler. Dir. Wayne Kramer. Lionsgate, 2003.

Cosgrave, James F., and Thomas R. Klassen. Casino State: Legalized Gambling in Canada.

Toronto: U of Toronto, 2009. Print.

"Disney Parks | Where Dreams Come True." Disney Parks | Where Dreams Come True. Disney,

n.d. Web. 22 Nov. 2014.

God of Gamblers. Dir. Wong Jing. Win's Movie Production & I/E Co. Ltd., 1989.

The Good Thief. Dir. Neil Jordan. Fox Searchlight, 2002.

Hard Eight. Dir. Paul Thomas Anderson. Goldwyn Films, 1996.

Horkheimer, Max, and Theodor W. Adorno. Dialectic of Enlightenment: Philosophical

Fragments. Ed. Gunzelin Schmid Noerr. Stanford, CA: Stanford UP, 2002. Print.

Miller, Kit. Inside the Glitter, Lives of Casino Workers: Photographs and Interviews. Carson

City, NV: Great Basin Pub., 2000. Print.

Ocean's Eleven. Dir. Steven Soderbergh. Warner Bros. Pictures, 2001.

Rounders. Dir. John. Dahl. Miramax Films, 1998.

12

Tazza: The High Rollers. Dir. Choi Choi Dong-hoon. CJ Entertainment, 2006.

"Tom Waits - Biography." IMDb. IMDb.com, n.d. Web. 24 Nov. 2014.

Warren, Liz, and Mooney, Courtney. "Pioneer Trail." (2011): n. pag.

LASVEGASNEVADA.GOV. City of Las Vegas Arts Commission / Historic Preservation

Commission. Web. 22 Nov. 2014.

!

!

13

© Copyright 2026