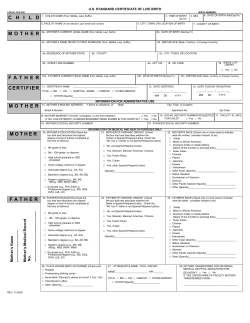

KNOWLEDGE, PERCEPTIONS AND PRACTICES IN PREGNANCY AND