Vanina Dal Bello-Haas, Anne D Kloos and Hiroshi Mitsumoto 1998; 78:1312-1324.

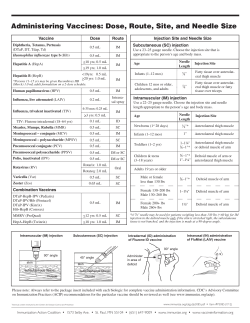

Physical Therapy for a Patient Through Six Stages of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Vanina Dal Bello-Haas, Anne D Kloos and Hiroshi Mitsumoto PHYS THER. 1998; 78:1312-1324. The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, can be found online at: http://ptjournal.apta.org/content/78/12/1312 Collections This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in the following collection(s): Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Case Reports Clinical Decision Making e-Letters To submit an e-Letter on this article, click here or click on "Submit a response" in the right-hand menu under "Responses" in the online version of this article. E-mail alerts Sign up here to receive free e-mail alerts Downloaded from http://ptjournal.apta.org/ by guest on September 9, 2014 Physical Therapy for a Patient Through Six Stages of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Background and Purpose. This case report describes the use of Sinaki and Mulder's approach to staging amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and functional outcome measures in designing a treatment program for a 59-year-old woman with ALS. Case Description and Outcomes. As the patient progressed from stage I through stage VI, over 12 months, the physical therapy goals changed from optimizing remaining function, to maintaining functional mobility, and finally to maximizing quality of life. Discussion. Disease staging and the use of functional outcome measures provide a framework for physical therapy evaluation and treatment of patients with ALS throughout the disease process. Physical therapists can assist patients with ALS through the provision of education, psychological support, rehabilitation programs, and recommendations for appropriate equipment and community resources. [Dal Bello-Haas V, Kloos AD, Mitsumoto H. Physical therapy for a patient through six stages of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Phys Ther. 1998;78:1312-1324.1 Key Words: Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Physical therapy, Staging of disease. Vaninu Dal Bellc+Haas I Anne D Kloos Hiroshi Mitsumoto Physical Therapy. Volume 78 . Number 12 . December 1998 Downloaded from http://ptjournal.apta.org/ by guest on September 9, 2014 Identification of stage of amyotrophic lateral myotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is the most common motoneuron disease among adults.' The incidence of ALS is 0.4 to 2.4 cases per 100,000 people worldwide, with a prevalence of 2.5 to 7 cases per 100,000 Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis is slightly more common in men than in women, and the average age of onset is the mid 50s. In 5% to 10% of people with ALS, the disease is inherited as an autosomal dominant trait and is referred to asfanzilial amyotrophic lateral ~clerosis.'-~ In 90% to 95% of people with ALS, there is no family history of the disease, and these people are said to have sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. In people with ALS, motoneurons in the spinal cord, brain stem, and cerebral motor cortex degenerate and result in a variety of signs and symptoms (Tab. 1).lr2The most frequent initial symptom, which occurs in more than 705%of patients, is focal weakness beginning in the leg, arm, or bulbar musc1es.l Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis is characterized by the absence of sensory symptoms and findings, although pathological conditions have been found in the sensory systems of some patients with ALS.1 Cognition, extraocular eye movements, and autonornic, bowel, bladder, and sexual functions usually remain intact. Muscle weakness progresses over time, and the pattern and rate of physical deterioration vary widely among individuals. Patients must cope with continual, multiple functional losses of speech, swallowing, mobility, and sclerosis can assist physical thetwpists in designing appropriate intervention. activities of daily living (ADL). Death from from respiratory failure, with 50% of patients surviving only 3 to 4 years after the onset of symptoms unless mechanical ventilation is used to sustain breathing.l.4 A major breakthrough in ALS research was made in 1993 with the discovery that some forms of familial ALS are caused by a mutation in the superoxide dismutase-1 (SOD-1) gene located on chromosome 21.5 Superoxide dismutase eliminates free radicals, which-although products of normal cell metabolism-are damaging to ~ - ~ suggested that cells. The results of some s t u d i e ~ have free-radical injury is also involved in cases of sporadic ALS. In addition, an unusual accumulation of neurofilaments, which are proteins that usually serve as a supporting structure in neurons, were found in motoneuron a~ons.~ Other J ~ researchers have found that levels of glutamate, an excitatory neurotransmitter, were elevated in cerebrospinal fluid1' and that glutamate uptake was decreased in the brain tissues of people with ALS.'2 Neuroscientists speculate that overstimulation of nerve cells by excessive amounts of glutamate could lead to cell death.' The immune system may also be involved in ALS because the serum of individuals with ALS has been V Dal BelleHaas, PT, is Assistant Professor, Department of Health Sciences, Cleveland State University, Health Science Bldg, Room 122, 2501 Euclid Ave, Cleveland, OH 441 15 (USA) ([email protected]). Address all correspondence to Ms Dal BelleHaas. AD Kloos, PT, is Research Physical Therapist, Department of Neurology, The Cleveland Clinic Foundation, Cleveland, Ohio. H Mitsumoto, MD, DSc, is Director of the Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Association Center, Department of Neurology, The Cleveland Clinic Foundation. This article was submitted Februaq 28, 1997, and was accepted August 6, 1998, Physical Therapy . Volume 78 . Number 12 . December 1998 Downloaded from http://ptjournal.apta.org/ by guest on September 9, 2014 Dal BelleHaas et al . 13 13 Table 1. Clinical Signs and Symptoms of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Upper Motoncuron Signs Lower Motoneuron Signs Spasticity Hyperreflexia Pathological reflexes Muscle weakness Muscle atrophy Fasciculations Hyporeflexia Hypotonicity Muscle cramps Bulbar Signs Respiratory Signs and Symptoms Other Signs and Symptoms Dysarthria Dysphagia Sialorrhea Pseudobulbar palsy Nocturnal respiratory difficulty Exertional dyspnea Accessory muscle use Paradoxical breathing Fatigue Weight loss Cachexia Tendon shortening Joint contractures shown to contain antibodies to motoneurons.13 Although these potential mechanisms are related to ALS, the pathogenesis of ALS is complex and remains unknown. No cure exists for ALS, but medications have beneficial effects. Riluzol (Rilutec) inhibits glutamate release and antagonizes the glutamate receptor, which prolongs survival.14 Myotrophin (insulin-like growth factor-I [IGF-I]) moderately lessens motor dysfunction, promoting the survival of motoneurons and regeneration of motor nerves.15 Riluzol is now available by prescription, and the US Food and Drug Administration has approved the use of IGF-I as an investigational new drug. Staging of Patients With ALS Sinaki and Mulder16J7 described the natural course of ALS as consisting of 6 stages. The stages are based on the progressive loss of function in the trunk and extremity muscles. Identification of a patient's stage can assist physical therapists in designing intervention throughout the disease process. Stage 1 The patient is in the early stages of the disease and is independent in mobility and ADL. A specific group of muscles are mildly weak, which may be manifested as limitations in performance or endurance, or both.16 Therapy consists of patient and caregiver education, energy conservation training, modification of the home and workplace, and psychological support. The patient is advised to continue normal physical activities. General active range of motion (AROM) and stretching of affected joints, resistive strengthening exercises of unaffected muscles with low to moderate weights, and aerobic activities (eg, swimming, walking, bicycling) at s u b maximal levels may be prescribed. Stage I1 The patient has moderate weakness in groups of muscles. The patient, for example, may have a foot drop on one or both sides or may have intrinsic muscle weakness in one hand that interferes with fine motor activities.16 Assessing the need for and providing appropriate equip13 14 . Dal BelleHaas et a1 ment and assistive devices to support weak muscles is the primary goal of intervention. The patient is encouraged to continue stretching and AROM exercises, strengthening exercises of unaffected muscles, and aerobic activities, as he or she is able. In addition, the patient and caregivers are instructed in performing active-assistedrange-of-motion (AAROM) and passive-range-of-motion (PROM) exercises of affected joints to prevent contractures. When designing a strengthening exercise program for a patient in ALS stages I and 11, the therapist should consider prevention of overuse fatiguela and disuse atrophy. Evidence from patients with some other neuromuscular diseases indicates that highly repetitive or heavy resistance exercise can cause permanent loss of force in weakened, denervated m u s ~ l e . ~ A " ~marked ~ reduction in activity level secondary to ALS, however, can lead to cardiovascular deconditioning and disuse weakness beyond the amount caused by the disease.22 Sinaki did not advocate any vigorous exercise for individuals with ALS, stating that "in most patients, no exercise other than that inherent in everyday ambulatory activities is indicated."l7(p170,Other authors, however, have reported beneficial effects of specific muscle strengthening and endurance exercise programs on patients with ALSZ3jz4 and other neuromuscular disea~es.Z~-~O Although functional gains as a result of exercise have not yet been determined, these st~dies,Z~-~O along with reports from our patients, suggest that exercise programs may be physiologically and psychologically beneficial for patients with ALS, especially when implemented before there is a great deal of muscle atrophy. Therefore, we have modified Sinaki and Mulder's framework to include muscle strengthening and endurance exercises when tolerated, particularly during the early stages of the disease. We continuously adjust the intensity of exercise to prevent excessive fatigue, while at the same time promoting use of intact muscle groups to perform functional activities. Patients are advised not to carry out any activities to the point of extreme fatigue (ie, inability to perform daily activities following exercise Physical Therapy . Volume 78 . Number 12 . December 1998 Downloaded from http://ptjournal.apta.org/ by guest on September 9, 2014 due to exhaustion, pain, fasciculations, or muscle cramping). Some individuals have cramping or fasciculations because of ALS; an increase in these lower motoneuron (LMN) symptoms may indicate overuse. Patients are also advised to exercise for several brief periods throughout the day, with sufficient rest between exercise sessions. The total daily exercise time is 30 to 45 minutes. This total daily exercise time would be divided into 2 or 3 sessions depending on the patient's tolerance, response to exercise, and daily schedule. The exercises may include resistive exercises, active exercises, and aerobic conditioning exercises (eg, cycling, walking, swimming). Stage 111 The patient remains ambulatory but has severe weakness in certain muscle groups that may result in severe foot drop or a markedly weak hand. The patient may be unable to stand up from a chair without help. Overall, the patient may exhibit mild to moderate limitation of function.16In this stage, as with all other stages, the goal is to keep the patient physically independent. Adaptive equipment (eg, ankle-foot orthoses [AFOs], splints, electrically powered height-adjustable chairs) may be needed to support weak muscles, decrease energy expenditure, and improve the patient's safety and mobility. Patients may begin to report heaviness and fatigue while holding their head up in this stage, and they may benefit from a soft collar. In addition, to avoid exhaustion, a wheelchair may become necessary when traveling long distances. Stage IV The patient in this stage has severe weakness of the legs and mild involvement of the arms. Thus, the patient uses a wheelchair and may be able to perform ADL.16 PROM and AAROM exercises are recommended to prevent contraclures. Strengthening exercises and AROM of any noninvolved muscles should be continued. As general mobility decreases, the need for instruction to inspect the skin for pressure areas increases, and sleeping and sitting systems that allow position changes and pressurerelief surfaces (eg, egg-crate bed cushion, alternatingpressure bed pad) may be recommended. Stage V This stage is characterized by progressive weakness and deterioration of mobility and endurance. The patient uses a wheelchair when out of bed, and arm muscles may exhibit moderate or severe weakness. Transferring the patient to and from a wheelchair becomes a major effort, and a lift may be necessary.I6 Patients become unable to move themselves in bed; thus, frequent repositioning and skin care by the caregiver are necessary. Pain may become a major problem in immobilized joints and needs to be addressed in the overall treatment plan. Pain is addressed according to the pathophysiology of the Physical Therapy . Volume 78 problem causing the pain. For example, pain due to spasticity or muscle cramping may be addressed by stretching and massage; pain due to contractures may be addressed by the use of thermal modalities, stretching, splinting, and soft tissue mobilization; pain to due joint hypomobility or acute injuries (eg, trauma to a shoulder resulting from a fall) may be addressed by joint mobilization, the use of thermal modalities, and electrical stimulation; pain due to joint instability may be addressed by the use of assistive devices, orthoses, slings, and positioning; and so on. Patients may be unable to hold their head up for extended periods. Thus, a semirigid collar (eg, Philadelphia collar,* Newport collart) is appropriate in this stage of the disease. If the patient has a tracheostomy, a Miamij c o ~ l a ror , ~a similar collar that allows for anterior neck access, is prescribed. By maintaining the head in a neutral position, breathing, eating, and seeing may be facilitated.' Stage VI The patient must remain in bed and requires maximal assistance with ADL. A hospital bed should be prescribed. Frequent repositioning of the body, padding to prevent uneven pressure, and prevention of venous stasis in the legs are crucial. Pain management continues to be important. "Head drop" from weak neck extensor muscles may become a major problem. Progressive respiratory distress develops in this stage, and a suction machine should be available.16 Cardiopulmonary physical therapy techniques may be required, such as body positioning to optimize ventilation-perfusion matching and prevent atelectasis; modified postural drainage positioning to decrease retention of secretions and aid in mobilization of secretions; self-assisted (if the patient is able) or manually assisted coughing techniques to compensate for a weak, ineffective cough and to aid in mobilization of secretions; and airway clearance techniques (ie, vibrations, shaking, percussions) to mobilize secreti~ns.~ Goals l in this stage are similar to those of hospice care: to address the patient's and caregivers' needs and to maximize the quality of each day. Nurses, aides, and caregivers are instructed in home programs depending on the patient's problems and needs (eg, PROM, stretching, transfers, massage, airway clearance techniques). In any stage of the disease, the patient may have respiratory problems or pain, or both. Deep breathing exercises, assisted coughing techniques, and airway clearance techniques may be recommended to address acute or chronic respiratory problems. Pain may occur as a result of previous musculoskeletal impairments (eg, patient ' Armstrong Medical Industries Inc, 575 Knightsbridge Pkwy, I.incolnshire, IL 60069. 'California Medical Products Inc, I901 Obispo Ave, Long Beach, CA 90804. 'Jerome C e ~ c a Spine l System, 305 Harper Dr, Moorestown, NJ 08057-3239. . Number 12 . December 1998 Downloaded from http://ptjournal.apta.org/ by guest on September 9, 2014 Dal BelleHaas et al . 1 3 15 may have concurrent osteoarthritis), spasticity, muscle cramping, weakness or atrophy, and joint instability caused by muscle imbalances and should be addressed accordingly. Examination and Evaluation for Patients With ALS Physical therapist examination and evaluation for patients with ALS throughout the stages of the disease is necessary to plan appropriate treatment programs. The tests we include in our assessment are used, along with general observation and patient report information, to determine the stage and rate of progression of the disease, to uniformly communicate patient status to other health care professionals, and to evaluate the effects of medical and physical therapy treatments. The Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Functional Rating Scale (ALSFRS)32is used to assess functional status and changes in patients (Appendix 1). The evaluator asks the patient (or the caregiver if the patient cannot speak) to rate his or her function for each of the 10 items of the ALSFRS on a scale ranging from 0 (unable to attempt the task) to 4 (normal function). The evaluator questions the patient by asking "How are you doing at..." and prompts the patient by using one of the available choices. Each scale item has criteria related to patient functioning, and the evaluator must have a thorough understanding of each item's criteria. In a study of 75 patients," the ALSFRS was found to correlate positikely with measures of upper-extremity and lower-extremity muscle force ( r = .88 and 3 6 , respectively) and demonstrated good internal consistency (Cronbach a= .815), test-retest reliability ( r = .88), and sensitivity to change. The Schwab and England Rating Scale (SERS) is an 1l-point global measure of function that asks the patient (or caregiver) to report ADL function from 0% (vegetative functions only) to 100% (normal) by circling the number that best corresponds to the phrase that describes the patient at the moment (Appendix 2).33 The ALS Ciliary Neurotrophic Factor Treatment Phase 1-11 Study Group found that the test-retest reliability of the SERS was excellent ( r =.94) and that SERS scores correlated well with qualitative and quantitative changes in patients' function.32 Assessment of motor function in individuals with ALS should include impairment and disability measures that can detect both upper motoneuron (UMN) and LMN loss. Quantitative muscle testing for these patients consists of measuring maximal voluntary isometric contractions (MVICs) of the shoulder extensors, elbow flexors, ankle dorsiflexors, knee extensors, and hip flexors using a strain gauge tensiometer system.34This method eliminates muscle length and contraction speed as factors in testing."-" Measurement of MVlCs is currently considered by some experts to be the most direct technique for investigating motor unit loss.34 Timed 4.6m (15-ft) walking tests assess the impact of physical impairments, such as reflex abnormalities, lower-extremity muscle weakness, and diminished motor control, on ambulation speed." The "PaTa" test, a test of bulbar function (oral-labial dexterity), requires the patient to repeat the syllables "PaTa" as many times as possible for 5 seco n d ~In. ~ patients ~ with ALS, the ability to perform a task may not change until a critical level of motoneuron loss is reached. Thus, the timing of motor tasks may be a less sensitive measure of disease progression than isometric muscle force testing using a t e n ~ i o m e t e r . ~ ~ , ~ ~ The modified Ashworth Spasticity Scale is a clinical measure of resistance to passive stretch that has been shown to produce reliable data.40,41Scores range from 0 (no increase in muscle tone) to 4 (affected parts rigid in flexion or extension) .40,41The Purdue Pegboard Test4' involves placing pins in a pegboard to assess right-hand and left-hand prehension, manual dexterity, and gross movement of the hands, fingers, and arms. Normative values are available, and the test has been used in various patient population^.^^ Pulmonary function has a marked impact on an individual's comfort, ability to communicate, and quality of life. Thus, forced vital capacity (FVC) and maximum inspiratory pressure (MIP), which are sensitive measures of respiratory f u n c t i ~ nare , ~ evalu~~~~ ated using a desktop spirometer.# Case Description Patient The patient was a 59-year-old woman who was referred to the multidisciplinary neuromuscular clinic at The Cleveland Clinic Foundation (Cleveland, Ohio). She reported that, 1 year prior to the initial clinic visit, she experienced cramping in her right hand and, later, slowly progressive hand weakness, especially with pinching maneuvers. One to 2 months before the initial visit, she noted that her feet "slapped" occasionally during walking, and she had painless twitching of the muscles in her right hand, forearm, and upper arm. She reported no respiratory or bulbar symptoms. The patient had been treated for ulcerative colitis for 20 years, and she had bilateral carpal tunnel releases in the year prior to experiencing cramping in her right hand. She lived with her husband in a house with 10 stairs to the basement with a railing on the right. She was not using any assistive devices at the time of the initial assessment. The patient and her husband had 4 grown "uritan-Bennett Corp, Boston Division, 265 Ballardvalle St, Wilmington. MA 01887. 13 16 . Dal Bello-Haas et al Physical Therapy . Volume 78 . Number 12 . December 1998 Downloaded from http://ptjournal.apta.org/ by guest on September 9, 2014 children, 2 of whom lived in the area. She described her family as very supportive. She was a homemaker who enjoyed knitting and golfing. She was right-handed. Neurological Examination A clinic:al examination revealed that the patient had a clonic jaw reflex; a positive nasolabial reflex; weakness, wasting, resistance to PROM, and pathological reflexes in both arms (positive Hoffman's sign); weakness and pathological reflexes in both legs (positive Babinski sign); and a positive Babinski reflex on the right side. Based on these findings, "definite ALS" was diagnosed by the neurologist because, according to the El Escorial riter ria,"^ the patient had "LMN signs [weakness, wasting] in at least 2 body regions and UMN signs [pathological reflexes, spasticity] in at least 1 body region, with UMN signs present above the level of LMN signs, and historical evidence of progressive disease" and all other disease processes were excluded. Electrornyographic studies showed (1) low compound motor action potentials in all extremities, (2) normal sensory nerve conduction, (3) fibrillations and fasciculations in all extremities, and (4) widespread neurogenic changes in motor unit action potentials, abnormal recruitment patterns in the arms, and mild to moderate changes in the distal leg musculature. These findings were consistent with an electrodiagnosis of motoneuron disease.'+(5 The pa~.ientand her family were informed about the diagnosis and the progressive nature of the disease. We believe it is important that the patient and family be given as much information as possible about the disease process, so that informed decisions about care can be made. At every stage of the disease, the patient participated in goal setting and treatment planning. Neurontin, a drug that is used in the treatment of epilepsy and that is thought to have antiglutamate properties, was prescribed for the patient. In addition, she was instructed to take antioxidative vitamins with all meals. Physical Therapy Examination The patient stated that she could perform all functional activities independently, but she noticed that she ascended and descended stairs more slowly than usual. Cutting meat was difficult, and she needed to rock fo~wardto stand up from a seated position. She also reported cramping in her calves in the evening. She had marked wasting of the interosseous muscles bilaterally. Range of motion (ROM) was normal for all joints, except the thumbs. She was only able to oppose her thumbs to the third digits. Bilateral lower-extremity strength was assessed as 5/5 on the Medical Research Council Scale,47except for the hip flexor group (right side=4/5, left side=4+/5). Shoulder muscle strength was assessed as 4-/5 (right side) and 4/5 (left side), and elbow muscle strength was assessed as 4/4 (right side) and 4+/5 (left side). Ashworth Spasticity Scale scores were 1+ for both arms and 1 for both legs. Grip strength was assessed using a Jamar adjustable hydraulic handheld dynamometerli (right hand=6 kg, left hand=12 kg). Balance was assessed by timing the duration of holding a unilateral stance (right side=l second, left side=2 seconds). Gait was independent of assistive devices and was negative for foot drop. Normal range for thumb opposition is considered the ability to touch the thumb to the top of the fifth finger. Some surgeons consider normal opposition as the ability to touch the base of the fifth digit with the tip of the t h ~ m b . ~ T hreliability e of ROM measurements varies among different j~ints.~"eliability testing of thumb ROM-has not been conducted. Using the Medical Research Council Scale, a grade of 5/5 is considered normal. The reliability of manual muscle test grades is low and varies depending on the strength of the musA grade of 0 on the modified Ashworth Spasticity Scale indicates "no increase in muscle tone" and would be considered "normal." Intrarater agreement has been reported as 86.7% agreement among raters, but testing was performed with the elbow flexors only.41 Normal values for grip strength using the Jamar dynamometer for a woman aged 60 years were reported as follows: right side=24.9?4.5 kg (55+ 10 Ib) , left side=20.9?4.5 kg (46k 10 Ib) ." Interrater reliability using the Jamar dynamometer was found to be 2.99, and test-retest reliability (1 week) was found to be 2.88.5"he duration that an individual can maintain single-leg stance is related to age. In individuals aged 50 to 59 years, Bohannon et a154 found that the mean time for one-legged timed balance was 29.4 seconds (SD= 2.9). Reliability testing results have not been published. The patient rated herself as 80% on the SERS." The FVC and MIP results indicated normal respiratory capacity. Walking speed was 3.4 seconds for the 4.6-m [15-ft] walk test, which was below the normal value of 5 2 seconds. Bulbar function was considered normal (ie, 15 times or more in 5 seconds)94;she repeated the "PaTa" test 15 times in 5 seconds. Hand function was severely impaired, as shown by the Purdue Pegboard Test where only 3 peg holes were filled in 30 seconds with the right hand and 2 peg holes were filled in 30 seconds with the left hand. The quantitative muscle testing and ALSFRS results are shown in Figure 1 and Table 2, respectively. We concluded that her arms were more affected than her legs, with distal muscle groups having greater weak"Therapeutic Equipment Corp. 60 Page Rd,Clifton, NJ 07012. Physical Therapy . Volume 78 . Number 12 . December 1998 Downloaded from http://ptjournal.apta.org/ by guest on September 9, 2014 Dol Bello-Haas et al . 1317 the shoulder and hip flexor muscles in sitting; self-stretching of thumb muscles; and aerobic exercise, using a stationary bicycle, at 65% of maximum heart rate for 10 minutes, 2 times per day. She was told about the effects of overwork fatigue on muscles, and she was told to avoid activities that required lifting greater than 6.8 kg (15 lb). The exercises were written up as a home program. Exercise sessions were limited to 20-minute sessions twice per day and to 10 repetitions of each AROM and resistive exercise. The use of AFOs and the purchase of a cane (for future use) were also Figure 1. discussed. She was given energy conMuscle force of a 56-year-old woman with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) at the time of servation information (eg, how to diagnosis. Distal muscles tended to be weaker than proximal muscles. Asterisk (*) indicates subject carry her laundry basket from the data from The National Isometric Muscle Strength Database Consortium. Muscular weakness assessment: use of normal isometric strength data. Arch Phys Med Rehobil. 1 9 9 6 ; 7 7 : 1 251 - 1 2 5 5 . basement), and home modifications to ease mobility were suggested (eg, sitting in raised chairs, using a raised Table 2. toilet seat). To relieve calf cramping, she was instructed Initial Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Functional Rating Scale 3 2 Scores in gastrocnemius muscle massage and stretching. of a 56-Year-Old W o m a n With Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Stretching was to be performed in a standing position, with the stretch held for 20 seconds, and repeated at Possible least 5 times in the morning and evening, or as required 1 Function Score Score when cramping occurred. She was referred for occupa1 Speech 4 3 tional therapy for a right wrist-thumb splint to be worn 1 Salivation 4 4 during activities, a resting hand splint to prevent claw1 Swallowing 4 4 ing, cylindrical foam for utensils to increase gripping 1 Handwriting (pre-ALS dominant hand) 4 3 ability, and instruction in dressing and bathing. The 1 Cutting food and handling utensils (patients patient and her husband were provided with informa4 or NA without gastrostomy) 3 Cutting food and handling utensils (patients tion about the local ALS support group. with gastrostomy) 1 Turning in bed; adjusting bed clothes Walking Climbing stairs Breathing Total score NA° 3 3 3 4 30 NA or 4 4 4 4 4 40 " NA=not applicable. ness than proximal muscle groups. Overall, these impairments appeared to have a mild impact on her ability to function. We determined that the patient was in stage I or II of ALS, because of the mild weakness in several muscle groups; marked weakness in the intrinsic muscles that interfered with handwriting, cutting foods, and handling utensils; and full independence in mobility and ADL. Thus, treatment included instruction in a general exercise program, which included resistive exercises of the lower-extremity muscles in lying with a 0.97-kg (2-lb) weight; AROM of hip flexor muscles; AROM exercises of 1318 . Dal Bello-Haas et al Three months after the initial evaluation (Figs. 2-4), the patient reported a mild, general increase in muscle weakness, especially in her right arm. Her speech was slower and slightly nasal, and she now needed to use the railing to ascend and descend stairs. She reported that the ROM exercises relieved the "stiffness" and pain in her right shoulder. She had fallen 1 week before this visit. Manual muscle test results and ROM of her arms and legs were unchanged from the previous visit, but quantitative muscle testing indicated decreased force in all muscle groups tested. The percentages of decrease in muscle force over the 3-month period between the initial assessment and reassessment were as follows: left shoulder extension = 21.9%, right shoulder extension = 4.8%, left elbow flexion = 15.2%, right elbow flexion = 19.7%, left grip force = 33.3%, right grip force = 25.0%, left hip flexion = 8.6%, right hip flexion = 31.7%, left knee extension =26.3%, right knee extension = 27.4%, left dorsiflexion = 21.4%, and right dorsiflexion = 25.0%. Bulbar func- Physical Therapy . Volume 7 8 . Number 12 . December 1998 Downloaded from http://ptjournal.apta.org/ by guest on September 9, 2014 J tion and overall general function had decreased from the previous visit. During walking, dorsiflexion was slightly decreased during heelstrike on both sides, although it was more pronounced on the right side. On the basis of the moderate weakness in the muscle groups and the m a signs of impending foot drop, we concluded that she was in stage I1 of M S . We advised her to continue her .> B exercises and to emphasize ROM $ 20 exercises in her right shoulder and 9 0 bilateral gastrocnemius muscle LL 0 I I I I I I I I I stretching exercises. Using clasped hands, she was to raise both arms 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 overhead in a lying position and use Months After Initial Evaluation the left arm to provide a pain-free stretch to the right shoulder at the Figure 2Changes in forced vital capacity during the course of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. The patient end of range, holding the stretch for reported shortness of b reath ~ on exertion when forced vital capacity was about 70% of normal. a count of 15. She was instructed in the use of a straight cane, and she and adult children were taught PROM and AAROM was givtsn a prescription for a right AFO. exercises for the affected muscle groups (10 repetitions done 2 to 3 times per day), slow stretching (hold-relax) Six months after the initial evaluation (Figs. 2-4), the patient reported increased right shoulder pain and techniques for the right shoulder, and transfer techincreasing muscle weakness of all extremities, especially niques using a gait belt to prevent pulling on her on the right side. Her speech was slurred, and she shoulders during transfers and further aggravate the right should pain. A left AFO was provided. occasioilally choked on spicy food and on her saliva. Left shoulder ROM was normal, but active right shoulder abduction and flexion were decreased by 20 and 80 Seven months after the initial evaluation (Figs. 2-4), the degrees, respectively. Ashworth scores were 1 for the legs patient enrolled in a clinical drug trial of brain-derived neurotrophic factor, which she said improved her and 2 for the arms. The decreased ROM and shoulder morale. She was still able to ambulate with a wheeled pain were attributed to increased spasticity about the walker, but she required more assistance with ADL. A shoulder. She could oppose her thumbs to the index finger only. Quantitative muscle testing showed totally electric hospital bed with a gel/foam overlay and decreases in force in all muscle groups. In addition, her a power reclining lift chair were ordered in anticipation 2.4m timed walk test result increased to 10.1 seconds. of future problems. The patient's husband reported that he was glad that he could assist her with her exercises There was no change in the "PaTa" test, although FVC because he felt like he was doing something to help her. decreased by approximately 22%. There appears to be a tendency for bulbar and respiratory function to decline concurrently, although this tendency has not been Nine months after the initial evaluation (Figs. 2-4), the proven. Motoneuron dysfunction is thought to spread patient stated that she was finding it more and more from one contiguous region to another. Because the difficult to think about the future and that she was cervical spinal cord segment innervating the diaphragm extremely saddened that she could not carry out her is the closest region of the spinal cord to the brain stem, traditional homemaking role, but had to rely on her it is expected that loss of bulbar function and loss of family to perforni ADL. She was extremely weepy and upper cervical motoneuron function would parallel each despondent at this visit. The physician was informed and other. The SERS and ALSFRS scores indicated a moderreferred her to a psychiatrist, who diagnosed her as ate decrease in overall function. having clinical depression and prescribed antidepressants. Her husband expressed difficulty in dealing with her disabilities; thus, a referral to a home care agency Because of severe weakness in several muscle groups and was made. A home health aide was provided, and a moderate limitation of overall function, she was deterniined to be in stage I11 of ALS. She started to use a referral to a home care physical therapist was made for wheeled walker for ambulation and a manual wheelchair PROM exercises and caregiver instruction on patient transferring and bed positioning techniques. The home for traveling long distances because of the muscle weakness and decreased respiratory function. Her husband care physical therapist initially performed the PROM C C Physical Therapy . Volume 78 . Number 12 . December 1998 Downloaded from http://ptjournal.apta.org/ by guest on September 9, 2014 Dal Bello-Haas et al . 13 19 a b 12 100 .- -m .- Pi7 ,"---------------------------- B 0 3 I 4 I 5 I 6 I 7 I 8 I I I , 9 1 0 1 1 1 2 1 3 0 3 I 4 Months After Initial Evaluation -E , 5 I 6 l 7 I 8 I , I ' I 9 1 0 1 1 1 2 1 3 Months After Initial Evaluation c d 40 7i 100 Stages V and VI In ':g 35 : ,--------------------- - ------ $4 4 A i 4 Stage III 0 1'01'1 11213 Months After Initial Evaluation I 3 4 I 5 I 6 I 7 I 8 I 9 10 I I 11 12 I 13 14 Months After Initial Evaluation Figure 3. (a) Changes in "PaTa" test scores during the course of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS]. Six months after the initial evaluation, the patient first reported that her speech was becoming slurred. (b) Changes in global functional ability (Schwab and England Rating Scale33 scores) during the course of ALS. Her scores declined almost 70% in 10 months. (c) Changes in the 6.8-m ( 1 5 4 ) timed-walk test scores during the course of ALS. Six months after the initiol evaluation, she began using a wheelchair when traveling long distances (30 m). Four months later, she became wheelchair-bound. (dl Changes in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Functional Rating Scale32 scores during the courseof ALS. Between the 8th and 14th months after the initial evaluation, her scores declined by almost 80%. exercises with the patient's husband observing and instructed the husband in performing the PROM exercises to ensure the correct technique. Ten months after the initial evaluation (Figs. 2-4), a wheelchair was the patient's primary means of mobility. She had shortness of breath on exertion, especially after moving short distances, but not when lying supine. In patients with ALS, in a seated or standing position, gravity assists the weakened diaphragm in depressing the abdominal contents during respiration. In a supine position, however, the abdominal contents are elevated, and the weakened diaphragm may be unable to depress the contents to allow for maximum inspiration, leading to shortness of breath. This was not the case for this patient. Her W C was 50% of predicted capacity, and she was now in stage IV of the disease. Because her W C had decreased to this level, she and her husband were shown assisted coughing techniques to compensate for the decreased force available for effective coughing. We have found that patients with an FVC of 50% or less of predicted capacity tend to decline rapidly. Thus, she was 1320 . Dal BelleHaas et al referred to a pulmonologist, who found her to be hypoxic. She declined noninvasive ventilation. Noninvasive ventilation (as opposed to tracheostomy) provides ventilatory support through oral or nasal masks and interfaces using portable ventilators.' Her main problem at this time was marked weight loss caused by eating difficulties secondary to spasticity in the jaw. We discussed inserting a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube if weight loss continued. She had discontinued using antidepressants because she was unable to tolerate the side effects and rehsed to try a different type. One year after the initial evaluation (Figs. 2-4), she could ambulate only 4.5 to 6.8 m (10-15 ft) before becoming fatigued. Although the patient's primary means of mobility was a wheelchair, she continued to ambulate short distances about the house. Her caregivers stated that transfers were now difficult because her knees would buckle and her legs became twisted. They continued the PROM program and assisted her in performing all of her self-care activities and ADL. She continued to lose weight, but declined a PEG tube. She Physical Therapy . Volume 78 Downloaded from http://ptjournal.apta.org/ by guest on September 9, 2014 . Number 12 . December 1998 Figure 4. Changes in muscle force of the legs and arms during the course of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. The increase in force of some muscles between the sixth and ninth months after the initial evaluation may be related to the increased spasticity noted at that time. DF=dorsiflexion. was referred for hospice care, and physical therapy recommendations (ie, caregiver instruction regarding Hoyer lift and sit-pivot transfers and positioning the patient in the wheelchair with a lap tray) were arranged with the coordinator. A Hoyer lift with a commode sling was ordered. A lap tray was recommended for her wheelchair to provide arm and trunk support. Her caregivers were instructed in sit-pivot transfers. By 14 months after the initial evaluation (Figs. 2-4), no new problems requiring physical therapy had emerged. She continued to decline noninvasive ventilation and a feeding tube. Fifteen months after the initial evaluation, she accepted noninvasive ventilation. Sixteen months after the initial evaluation, her family informed us of her death. Discussion Despite the poor prognosis of ALS, we believe that physical therapy is an important component of the overall care of patients with this disease. We believe that patients with ALS may exhibit a variety of emotions related to the changes and functional losses that they experience. Depression, hostility, anger, denial, and despair are responses with which they may need to dea1.l~ Through ~~ active participation in goal setting and treatment planning, patients may gain some sense of control over what is happening to their bodies, enabling them to better cope with functional losses. Throughout all stages of the disease, therapists must assess the patients' coping mechanisms, watch for signs of depression, refer the patients to other health care professionals as necessary, assist them in making life choices, and provide psychological support to the patients and caregivers. The patient and her husband, for example, often told us how beneficial physical therapy was to them, especially the exercise prescription and the information about mobility and assistive devices. Physical therapists call assist patients with ALS throughout all stages of the disease through the provision of education, psychological support, rehabilitation programs, and recommendations for appropriate equipment and community resources. Research is needed to determine whether physical therapy beginning during the early stages of ALS can reduce the incidence of falls and the development of severe contractures, painful joints, and skin breakdown. Avoidance of these complications might maintain the patient's mobility and function for a longer duration, thereby decreasing the patient's need for assistance with ADL and transfers from caregivers. More research on exercise and rehabilitation programs is also needed if therapists are to make evidence-based decisions regarding other therapeutic intelventions. Randomized studies that compare the effects of different exercise programs in terms of type, frequency, duration, and intensity of exercises, for example, are needed. Outcome measures should include not only force measurements but, more importantly, functional and quality-of-life measures. As new medications that slow the progression of the disease become available, studies are needed to assess the combined effects of medications and exercise on the functional abilities and quality of life of patients. We believe that our expanded version of Sinaki and Mulder's approach to staging patients with ALS and the use of functional outcome measures aid in planning appropriate treatment programs that not only address the patient's current physical and psychological problems, but also take into account the patient's future needs. We also believe that physical therapists' care and compassion can have an impact on the well-being of people living with this disease. References 1 Mitsumoto H, Chad DA, Pioro EK. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Philadelphia, Pa: FA Davis Co; 1998. Physical Therapy . Volume 7 8 . Number 12 . December 1998 Downloaded from http://ptjournal.apta.org/ by guest on September 9, 2014 Dal BelleHaas et al . 1321 2 Juergens SM, Kurland KT. Epidemiology. In: Mulder D, ed. The Diagnosis and Treatment of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclmosis. Boston, Mass: Houghton Mimin Co; 1980:35-46. 3 Tandan R, Bradley WG. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, part 1: clinical features, pathology, and ethical issues in management. Ann Neurol. 1985;18:271-180. 4 Dworkin JP, Hartman DE. Progressive speech deterioration and dysphagia in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: case report. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1979;60:423-425. 5 Rosen DR, Siddique T, Patterson D, et al. Mutations in Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase gene are associated with familial arnyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nature. 1993;362:59-62. 6 Bredesen DE, Ellerby LM, Hart PJ, et al. Do posttranslational modifications of CuZnSOD lead to sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis? Ann Neurol. 1997;42:135-137. 7 Bowling AC, Schulz JB, Brown RH Jr, Beal MF. Superoxide dismutase activity, oxidative damage, and mitochondria1 energy metabolism in familial and sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J ~eurochem.1993; 61:2322-2325. 8 Kawamata J, Shimohama S, Takano S, et al. Novel G16S (GGC-AGC) mutation in the SOD-1 gene in a patient with apparently sporadic young-onset amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Hum Mutat. 1997;9:356-358. 9 Hirano .4. Cytopathology in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Adv Neurol. 1991;56:91-101. 10 Collard JF, Cote F, Julien JP. Defective axonal transport in a transgenic mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nature. 1995;375:61-64. 11 Rothstein JD, Tsai GT, Kuncl RW, et al. Abnormal excitatory amino acid metabolism in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 1990;28: 18-25. 12 Rothstein JD, Martin LJ, Kuncl RW. Decreased glutamate transport by the brain and spinal cord in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. N Engl JMed. 1992;236:1464-1468. 13 Appel SH, Stockton-Appel V, Stewart SS, Kerman RH. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: associated clinical disorders and immunological evaluations. Arch Neurol. 1986;43:234-238. 14 Bensimon G, Lacomblez L, Meininger V. A controlled trial of riluzole in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis:- ALS/Riluzole Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:585-591. 15 Lange DJ, Felice KJ, Festoff BW, et al. Recombinant human insulinlike growth factor-I in ALS: description of a double-blind, placebocontrolled study-North American ALS/IGF-I Study Group. Neurology. 1996;47(4 suppl 2):S93494; discussion S94-S95. 16 Sinaki M, Mulder DW. Rehabilitation techniques for patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Mayo Clin Proc. 1978;53:173-178. 17 Sinaki M. Rehabilitation. In: Mulder DW, ed. The Diagnosis and Treatment of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Boston, Mass: Houghton Mifflin Co; 1980:171-193. 18 Bennett RL, Knowlton GC. Overwork weakness in partially denervated skeletal muscle. Clin Orthop. 1958;12:22-29. 19 Smith RA, Norris FH Jr. Symptomatic care of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J M . 1975;234:715-717. 20 Wagner MB, Vignos PJ Jr, Fonow DC. Serial isokinetic evaluations used for a patient with scapuloperoneal muscular dystrophy: a case report. Phys Ther. 1986;66:1110-1113. 21 Peach PE. Overwork weakness with evidence of muscle damage in a patient with residual paralysis from polio. Arch Phjs Med Rehabil. 1990;71:248-250. 1322 . Dal Bello-Haas et al 22 Norris FH. Exercise for patients with neuromuscular diseases. West JMed. 1985;142:261. 23 Bohannon RW. Results of resistance exercise on a patient with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a case report. Phys Ther. 1983;63:965-968. 24 Sanjak M, Paulson D, Sufit R, et al. Physiologic and metabolic response to progressive and prolonged exercise in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurology. 1987;37:1217-1220. 25 Kilmer DD, McCrory MA, Wright NC, et al. The effect of a highresistance exercise program in slowly progressive neuromuscular disease. Arch Phys ~ e d R e h a b i 1 1994;75:560-563. . 26 Lindeman E, Leffers P, Spaans F, et al. Strength training in patients with myotonic dystrophy and hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy: a randomized clinical trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1995;76: 612-620. 27Aitkens SG, McCrory MA, Kilmer DD, Bemauer EM. Moderate resistance exercise program: its effect in slowly progressive neuromuscular disease. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1993;74:711-715. 28 Milner-Brown HS, Miller RG. Muscle strengthening through electric stimulation combined with low-resistance weights in patient? with neuromuscular disorders. Arch Phys iMed Rehabil. 1988;69:20-24. 29 Wright NC, Kilmer DD, McCrory MA, et al. Aerobic walking in slowly progressive neuromuscular disease: effect of a 12-week program. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1996;77:64-69. 3OFlorence JM, Hagberg JM. Effect of training on the exercise responses of neuromuscular disease patients. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1984;16:460-465. 31 Frownfelter D, Dean E. Principb and Practice of Cardwpulmonaq Physical Therapy. 3rd ed. St Louis, Mo: CV Mosby Co; 1996. 32 The ALS Ciliary Neurotrophic Factor Treatment Study (ACTS) Phase 1-11 Study Group. The amyotrophic lateral sclerosis functional rating scale: assessment of activities of daily living in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Arch Neural. 1996;53:141-147. 33 Schwab R, England A. Projection technique for evaluating surgery in Parkinson's disease. In: Gillingham J, Donaldson I, eds. Third Symposium on Parkinson's Disease. Edinburgh, Scotland: Churchill Livingstone; 1969:152-157. 34 Andres PL, Hedlund W, Finison L, et al. Quantitative motor assessment in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurology. 1986;36:937-941. 35 de Boer A, Boukes RJ, Sterk JC. Reliability of dynamometry in patients with a neuromuscular disorder. N Lngl J Med. 1982;11:169174. 36 Scott OM, Hyde SA, Goddard C, Dubowitz V. Quantitation of muscle function in children: a prospective study in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Muscle N m e . 1982;5:291-301. 37 Wiles CM, KarniY. The measurement of muscle strength in patients with peripheral neuromuscular disorders. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatq. 1983;46:1006-1013. 38 Wade DT. Measurem~nt in Neurological Rehabilitation. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 1992. 39 Fletcher SG. Time-by-count measurement of diadochokinetic syllable rate. JSpeech Hear Res. 1972;15:763-770. 40 Ashworth B. Preliminary trial of carisoprodol in multiple sclerosis. Practitioner. 1964;192:540-544. 41 Bohannon RW, Smith MB. Interrater reliability of a modified Ashworth scale of muscle spasticity. Phys Ther. 1987;67:206-207. 42 Smith HD. Assessment and evaluation: an overview. In: Hopkins HL, Smith HD, eds. Willard and Spackman's Occupational Therapy. 7th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: JB Lippincott Co; 1993:227. . Physical Therapy Volume 78 Downloaded from http://ptjournal.apta.org/ by guest on September 9, 2014 . Number 12 . December 1998 43 Griggs RC, Donohoe KM, Utell MJ, et al. Evaluation of pulmonary function in neuromuscular disease. Arch Neurol. 1981;38:9-12. 44 Fallat RJ, Jewitt B, Bass M, et al. Spirometry in amyotrophic lateral 50 Wadsworth CT, Krishnan R, Sear M, et al. Intrarater reliability of manual muscle testing and hand-held dynametric muscle testing. Phys Ther. 1987;67:1342-1 347. sclerosis. .4rch Neurol. 1979;36:74-80. 51 Frese E, Brown M, Norton BJ. Clinical reliability of manual muscle 45 The World Federation of Neurology Research Group on Neuromus- testing: middle trapezius and gluteus medius muscles. Phys Ther. 1987;67:1072-1076. cular Diseases, Subcommittee on Motor Neuron Disease. El Escorial World Federation of Neurology criteria for the diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol Sci. 1994;124(suppl):96-107. 46 Bannister R. Brain's Clinical Neurology. 6th ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press Inc; 1985. 47 Medical Research Council. Aids lo the Examination of the Pm9heral 52 Mathiowetz V, Kashman N, Volland G, et a]. Grip and pinch strength: normative data for adults. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1985;66:69-74. 53 Mathiowetz V, Weber K, Volland G, Kashman N. Reliability and validity of grip and pinch strength evaluations. J Hand Surg Atn. 1984;9:222-226. Nervous System. London, England: Her Majesty's Stationary Ofice; 19%. 54 Bohannon RW, Larkin PA, Cook AC, et al. Decrease in timed balance test scores with aging. Phys Ther. 1984;64:1067-1070. of 55 McDonald E. Psychosocial-spiritual o v e ~ e w .In: Mitsumoto H, 48 American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Joint Motion: Method Measuring and &cording. 11th ed. New York, NY: Churchill Livingstone Inc; 1983. Norris FH Jr, eds. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: A Comprehensive Guide to Management. New York, NY: Demos Publications; 1994:205-227. 49 Rothstein JM, Miller PJ, Roettger RF. Goniometric reliability in the clinical setting: elbow and knee measurements. Phys Ther. 1983;63: 161 1-161.5. Appendix 1. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Functional Rating Scale32 1. Speech 4 Normal speech processes 3 2 1 0 Detectable speech disturbance Intelligible with repeating Speech combined with nonvocal communication Loss of useful speech 2. Salivation 4 Normal 3 2 1 0 2 1 0 Slight but definite excess of saliva in mouth; may have nighttime drooling Moderately excessive saliva; may have minimal drooling Marked excess of saliva with some drooling Marked drooling; requires constant tissue or handkerchief Normal eating habits Early eating problems; occasional choking Dietary consistency changes Needs supplemental tube feeding Nothing by mouth (exclusively parenteral or enteral feeding] 0 Slow or sloppy; all words are legible Not all words are legible Able to grip pen, but unable to write Unable to grip pen 2 1 0 3 2 1 0 1 0 0 5b.Cutting food and handling utensils (alternate scale for patients with gastrostomy) 4 Normal Early ambulation difficulties Walks with assistance Nonambulatory functional movement only N o purposeful leg movement 9. Climbing stairs 4 Normal 3 2 0 Somewhat slow and clumsy, but no help needed Can turn alone or adjust sheets, but with great difficulty Can initiate, but not turn or adjust, sheets alone Helpless 8. Walking 4 Normal 3 1 lnde endent and complete selfcare with effort or decreased ePciency lntermittent assistance or substitute methods Needs attendant for selfcare Total dependence 7. Turning in bed and adjusting bed clothes 4 Normal 5a.Cutting food and handling utensils (patients without gastrostomy) 4 Normal Somewhat slow and clumsy, but no help needed Can cut most foods, although clumsy and slow; some help needed Food must be cut by someone, but can still feed self slowly Needs to be fed Clumsy, but able to perform all manipulations independently Some help needed with closures and fasteners Provides minimal assistance to caregiver Unable to perform any aspect of task 6. Dressing and hygiene 4 Normal function 3 2 4. Handwriting 4 Normal 3 2 1 0 3 3. Swallowing 4 3 3 2 1 2 1 Slow Mild unsteadiness or fatigue Needs assistance Cannot do 10. Breathing 4 Normal 3 2 1 0 Shortness of breath with minimal exertion (eg, walking, talking) Shortness of breath at rest lntermittent (eg, nocturnal) ventilatory assistance Ventilatordeoendent - Physical Therapy . Volume 78 . Number 12 . December 1998 Downloaded from http://ptjournal.apta.org/ by guest on September 9, 2014 Dal Bello-Haas et al . 1323 A pendix 2. Scffwab and England Rating Scale33 1OO%=Completely independent; able to do all chores without slowness, difficulty, or impairment; essentially normal; unaware of any difficulty 90%=Completely independent; able to do all chores with some degree of slowness, difficulty, and impairment; may take twice as long as usual; beginning to be aware of difficulty 80%=Completely independent in most chores; takes twice as long as normal; conscious of difficulty and slowness 70%=Not completely independent; more difficulty with some chores; takes 3-4 times as long as normal in some chores, must spend a large part of the day with some chores 60%=Some dependency; can do most chores, but exceedingly slowly and with considerable effort and errors; some chores impossible 50%=More dependent; needs help with half the chores, slower, and so on; difficulty with everything 40%=Very dependent; can assist with all chores, but does few alone 30%=With effort, now and then does a few chores alone or begins chores alone; much help needed 20%=Does nothing alone; can be a slight help with some chores; severe invalidity 1 O%=Totally dependent and helpless; complete invalidity O%=Vegetative functions such as swallowing, bladder, and bowels are not functioning; bedridden Physical Therapy is going online! Beginning January 1999 the information you value most will be available to you within seconds. Don't be the last to know the latest on patient and practice management, physical therapy research, and education. Physical Therapy online will be available only to APTA members and Journal subscribers. Become an APTA member today at www.apta.org to gain access to this valuable tool. 1324 . Dal BelleHaas et al Physical Therapy . Volume 78 Downloaded from http://ptjournal.apta.org/ by guest on September 9, 2014 . Number 12 . December 1998 Physical Therapy for a Patient Through Six Stages of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Vanina Dal Bello-Haas, Anne D Kloos and Hiroshi Mitsumoto PHYS THER. 1998; 78:1312-1324. This article has been cited by 3 HighWire-hosted articles: Cited by http://ptjournal.apta.org/content/78/12/1312#otherarticles http://ptjournal.apta.org/subscriptions/ Subscription Information Permissions and Reprints http://ptjournal.apta.org/site/misc/terms.xhtml Information for Authors http://ptjournal.apta.org/site/misc/ifora.xhtml Downloaded from http://ptjournal.apta.org/ by guest on September 9, 2014

© Copyright 2026