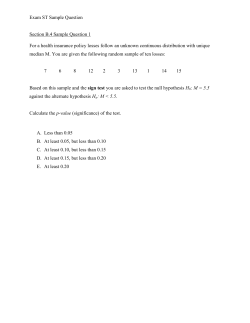

special report on the financial strength of kentucky`s