Miami green bytes - Miami-Dade County Extension Office

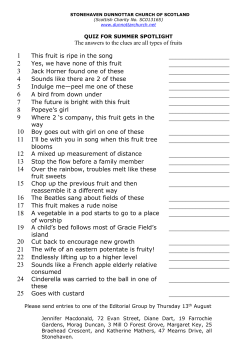

Spring 2015 Miami green bytes . Predictions of a cooler and wetter winter have not materialized so far with conditions having been milder and drier than normal, though not as mild as the previous three winters. An extended period of cool weather during December plus below normal rain fall helped to ensure early flowering of mango trees, and even some lychees. Rainfall has been spotty with conditions over South Florida officially abnormally dry, far interior Miami-Dade (Everglades) suffering a moderate drought. Weak El Nino conditions have developed but are not expected to exert a major influence on climate at present. For the next 90 days both temperatures and rainfall are expected to be above normal. why you need to take precautions when working outdoors. Barbara McAdam reveals a late passion for orchids. no, it isn’t about pesticides but using common household articles. add both eye and nose appeal to your landscape . A Safety when working outdoors, be it a backyard gardener, selection of myrtaceous shrubs and professional arborist, nurseryman or grower, often stops at the obvious small trees with edible fruit. - physical injury from over exertion (e.g., dehydration), and improper use of equipment (such as power saws) and chemicals (such as Plus the regular ‘Pest pesticides). Several calls concerning distress over removing Brazilian Update’ & ‘At this time of pepper acted as a reminder of the potential hazards faced when year…’ working around plants. Specifically skin contact with plants, which can lead to distress in the form of various degrees of skin irritation (contact dermatitis). Contact may involve intact plant surfaces, sap from torn leaves or broken stems, as well as crushed fruit. There are three types of contact dermatitis, Irritant dermatitis results from a toxin or direct two of which produce symptoms within minutes (irritant mechanical and /or chemical damage to the skin dermatitis and immunologic contact urticaria) and (does not involve immune system). delayed contact dermatitis where symptoms appear 24-48 Immunologic contact urticaria is an immediate hours after exposure (see text box for more details. type hypersensitivity reaction which rapidly Irritant dermatitis due to mechanical damage can be due to various out growths of the plant epidermis termed trichomes (various hairs, bristles, scales and prickles) including for instance: Glochids – barbed bristles found on Opuntia spp. (‘prickly pear’, the most widespread genus of cacti). Abrasive bristles - figs and mulberries Burrs and fine hairs – various grasses In addition many plants have more conspicuous prickles (and spines); apart from any skin irritation these may also on occasion transfer microorganisms capable of causing disease (e.g., the fungus Sporothrix schenckii on rose prickles). manifests as intense itching and welts. This reaction is in response to the presence of foreign proteins and is mediated by production of a specific antibody (IgE). This type of allergic response to contact with plants is rare involving people who are atopic (sensitive to a greater range of substances and overproduce IgE), and is far more important in relation to contact with pollen (hay fever). [Antibodies (immunoglobulins, Ig) are proteins that help neutralize what the body perceives as ‘foreign’]. Delayed contact dermatitis develops 24-48 hours after exposure to various low molecular weight compounds (e.g., components in plant sap) to which an individual becomes sensitized, and involves cytotoxic cells (rather than antibodies) of the immune system. Factors released by these cells (stimulated by the compound to which you are sensitized) cause the reddening (erythema), intense itching (pruritis) and numerous small to large fluid filled blisters. The compounds in the plant sap to which you become sensitized act as haptens. After penetrating the skin surface haptens bond with normal body proteins making them appear ‘foreign’ which then elicits the above cellular immune response. Toxins introduced by hollow stinging hairs are found in members of the Urticaceae and Euphorbiaceae. In both instances the toxin is released as the hairs pierce the skin. The Urticaceae includes a variety of plants known collectively as nettles; in Miami-Dade only one species has been reported, Laportea aestuans the West Indian wood nettle, a non-native annual reported to be quite common in the Redlands. Contact with leaves results in burning pain and painful blisters, an effect that is lost once leaves are dried. Fortunately we do not have anything similar to the infamous nettle trees (Dendrocnide spp.) found in Australia’s east coast rain forests where intense pain can last for weeks and deaths have been reported. The bull nettle also known as tread-softly (Cnidoscolus stimulosus) is a euphorb found throughout Florida which thrives in full sun on open waste ground and degraded pasture, particularly where the soil is dry and sandy. Bull nettles certainly sting (likened to fire ants) but they also have quite attractive white flowers; although native they are best removed (carefully!). A related shrub C. acontifolius subsp. acontifolius (chaya also known as tree spinach) is grown for its edible leaves (after cooking); cultivated plants have been chosen that have far fewer stinging hairs. The velvet (or cow-itch) bean Mucuna pruriens is an exotic vine found in the southern-most counties of Florida. In Miami-Dade it occurs along roadsides as well as several conservation areas containing native plant communities. The pods (shown at left) are covered with spicules which, on contact with skin, cause intense pruritis (itching). Symptoms are not due to mechanical irritation, but to a cysteine proteinase (mucunain) that coats the spicules and triggers the itching response. Varieties used as cover crops do not have irritant spicules. Chemical irritant dermatitis involves exposure of skin to chemical compounds of plant origin which cause direct damage (does not involve prior sensitization). Velvet bean Plants of the spurge family Euphorbiaceae contain not only some of the most deadly of all plant toxins (e.g., ricin), but depending on the species the lactiferous sap (latex) can cause severe irritant dermatitis. The irritants involved, diterpene esters (especially phorbol esters), are found in both the latex and seeds of many euphorbs. If taken internally they can cause severe poisoning. Skin contact with latex results in a range of symptoms from mild skin irritation to localized swelling and severe blistering, while contact with the eyes cause intense burning and possible temporary blurred vision. Phorbol esters have been implicated as co-carcinogens (i.e., they are not directly carcinogenic, but may promote cancer in concert with other factors that initiate carcinogenesis). The most common Euphorbia found in local landscapes is crown-ofthorns, Euphorbia milii, especially the many cultivars that have been developed. The latex from crown-of-thorns usually causes a mild to moderate irritant dermatitis compared to the more severe symptoms seen in the large ‘cactus’ euphorbs such as Euphobia tirucalli (pencil cactus shown at left) - note that true cacti do not have milky latex. In local landscapes pencil cactus latex can cause intense inflammation and blistering of skin (which can be slow to heal) and severe eye injury. It is a large plant with many thin brittle branches which break easily releasing a stream of latex making it especially hazardous to prune. Although pencil cactus has become rarer in local landscapes, small plants are sometimes seen in the succulent section of garden shops (intended for windowsill use) including a cultivar sold as ‘Sticks on Fire’ with numerous thin orangey red tipped stems. This and Euphorbia trigona (African milk tree or cathedral cactus shown right)), another potentially large species, should be placed where they are inaccessible to children. This latter euphorb is also available in a striking red form and where used as a potted patio plant eventually becomes too large and unwieldy - easily toppled, especially if the spines catch on clothing. The candelabra cactus (Euphorbia lactea) is another large species with especially toxic latex, though now more usually seen in one of several dwarf cristate forms. Highly ornamental, looking like pieces of coral, they are usually grafted onto Euphorbia neriifolia also with poisonous latex). Aroids (Araceae) make up the bulk of plant species most frequently encountered by poison control centers. Of particular concern are Rhaphides from Epiprenum Dieffenbachia (dumb cane) and to a lesser degree aureum (mag. 600x) Spathiphyllum (peace lily), Anthurium, Aglaonema (Chinese evegreen), Colocasia (taro), Epipremnum (pothos vine), Zantedeschia (calla lilies) and Caladium. They all contain oxalic acid, both free and as microscopic needle-like crystals of calcium oxalate (raphides), located in special mucilage containing cells (idioblasts). When the leaf/stem of an aroid is crushed (or chewed) the idioblast tips break off. The mucilage then swells as it absorb water affecting a rapid mass expulsion of raphides. On contact with sap from broken aroid stems, the released raphides can cause localized irritant dermatitis and eye injury. If a rash develops after trimming trees or cleaning up after a storm, check to see if you removed any vines having succulent stems and large green cordate (heart shaped) or pinnatifid (highly lobed) leaves. If so, this is probably the pothos vine (Epipremnum pinnatum). The cultivar ‘Aureum’ with boldly variegated green and yellow leaves, is more often seen (also listed as a separate species E. aureum. Potentially more serious, biting into an aroid results in vast numbers of raphides piercing the mucosa of the mouth and throat like tiny shards of glass. Due to an almost instantaneous severe burning sensation, it is rare that sufficient plant material is ingested for aroids to cause serious complications – most at risk are young children. Philodendron spp. possess irritant raphides, but in addition also contain Idioblast isolated from Dieffenbachia Caution when handling palms Palm fruits containing more than 8 mg Ca oxalate/g (dry weight) are liable to cause skin irritation. Apart from fishtail palms and dwarf sugar palms other landscape palms with fruit containing high concentrations of oxalate include: Buccaneer palm (Pseudophoenix sargentii), Macarthur palm (Ptychosperma macarthurii) Royal palm (Roystonea regia) Hurricane palm (Dictyospermum album), Spindle palm (Hyophorbe verschaffeltii) and several Chamadorea spp. (especially C. If you collect fruit from these palms for propagation wear long rubber gloves when cleaning flesh from the seeds. costariciana). ©Wunderlin, R.P. & B.F. Hansen alkenyl resorcinols (a type of phenolic 2008 USF Atlas of Vascular Plants lipid – see poison ivy below). These have been associated with a delayed type contact dermatitis that develops in susceptible individuals after repeated contact with philodendrons over months or years. More often found in growers and nursery workers. Apart from aroids, raphides occur widely in many other monocotyledons; in the Arecacae (palms) raphides are found in stems, roots, leaves and even flowers. Especially high concentrations are found in the fruits of several palm species grown in local landscapes as those who have handled fruits of fishtail palms (Caryota spp.) can attest. Fruit of the related dwarf sugar palm Arenga tremula contains 1.5x as much oxalate as fishtail palms. Both palms are hapaxanthic (stems slowly die once they bear fruit at which time they are usually removed). One option is to remove the inflorescence before fruit sets, or to first carefully remove fruit, then cut down the stem. Some individuals are also liable to skin irritation when handling cut fronds and stems, so cover-up (gloves, long sleeved shirt/blouse and pants and work shoes) and wear eye protection. Another family of monocotyledons, Agavaceae (Agave americana, the century plant is most familiar) form six sided raphides and also contain saponins (compounds consisting of a complex triterpenoid, or steroid core, to which one or more sugars are attached). Found in various plant families, a few are highly poisonous when taken internally, while others can cause severe skin irritation. The latter are found in agaves and aggravate the mechanical damage inflicted by raphides. While landscape agaves are only rarely reported as the cause of contact dermatitis, workers in tequila distilleries as well as those tending agave plantations commonly suffer severe skin irritation. The fact that most agaves possess fearsome spines no doubt warns people to be on their guard. If you need to remove a large agave (e.g., after flowering when they die) don protective eye wear, gloves and a long sleeved shirt and use a long handled cactus saw (definitely not a chain saw!). While raphides are mostly found in monocotyledons they also occur, to varying degrees, in 27 dicotyledon families. Among these, the Vitaceae (grape family) contain two locally occurring vines that on occasion cause a mild to moderate irritant dermatitis. The first Virginia creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia) bears a Above Virginia creeper (5 leaflets almost sessile), below poison ivy (3 leaflets, only opposite pair appear sessile. superficial resemblance to poison ivy, which has led to their mis- identification (see photos below for comparison). A local landscape crew clearing vines from an overgrown lot experienced intense localized itching, inflammation and swelling, and suspected poison ivy. Samples of the vine brought to Miami-Dade Extension were identified as Virginia creeper. Unlike poison ivy, which produces a delayed contact dermatitis 24-48 h after exposure (see below), symptoms due to Virginia creeper develop far more rapidly, the result of contact with sap from broken stems and bruised/shredded leaves. The Aerial roots of princess vine possum grape (Cissus verticillata, also known as princess or curtain vine) also causes reddening and irritation of exposed skin, again only if contact is with damaged stems and leaves. In the Solanaceae (potato family) chili peppers (Capsicum spp.) contain capsaicin an alkyl amide responsible for their pungent taste. They can also cause an immediate irritant reddening of the skin (erythema) but no blistering and extremely painful eye discomfort. Rubber gloves are a dvisable when handling chili peppers. Phytophotodermatis is a type of chemical irritant dermatitis in which contact with a class of plant chemicals (furanocoumarins) sensitizes the skin to sunlight. Following contact and subsequent exposure of skin to sunlight, severe erythema and blistering develop over the next 48 hours often followed by a period of prolonged hyperpigmentation of affected skin. Contact with the leaves of Ficus carica (edible fig), which contain furanocoumarins has on various occasions been recorded as the cause of phytophotodermatitis and it may well be under diagnosed. Members of the Rutaceae also possess photosensitizing Dermatitis after handling limes followed by furanocoumarins; bergapten (first found in oil of bergamot subsequent sun exposure from Citrus bergamia) is in large part responsible for the photo- dermatitis that can follow contact with lemons and especialy limes (more so Persian than Key limes). Delayed contact dermatitis Two families, Asteraceae and Anacardiaceae are the principal sources of plants where symptoms of dermatitis are delayed and occur in response to prior sensitization (involves immune system). Members of the Anacardiaceae are responsible for more cases of contact dermatitis in the U.S. than all other plants combined. Of these by far the most important are five species of Toxicodendron - eastern and western poison oak, poison sumac and eastern and western poison ivy. Only eastern poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans) is found in south Florida and in Miami-Dade it is infrequent in residential areas, preferring moist wooded sites. Sap from all these plant contains oily phenolic lipids, urushiols (alkenyl catechols) that readily penetrate the outer layers of skin. They are then susceptible to oxidiation to more reactive quinones which act as haptens and bind to proteins on the surface of white blood cells deeper in the skin. These modified proteins are recognized as ‘foreign’ (antigens) and prime the body’s immune system, sensitizing susceptible individuals to further exposure. While initial contact may elicit a mild skin response up to 2 weeks later, subsequent contact with urushiols causes a far more pronounced delayed type contact dermatitis (after 24 – 48 h, see photo at right). Even though poison ivy is not commonly encountered in Miami-Dade, contact need not only be with the plant, but surfaces contaminated with sap can also elicit a response. This could include items such as clothing, bagged mulch and animal fur (urushiols are only allergenic to humans and other primates). In addition urushiols remain allergenic for many months (or years in cool dry climates). In the absence of treatment, full recovery from poison ivy dermatitis takes about 3 weeks depending on the degree of sensitivity and extent of exposure. Approximately 10 – 15% of the US population is tolerant (do not react) to urushiol exposure, with up to 75 % in a given area sensitized (far fewer in large urban centers where there is less greenery). The degree of sensitivity varies and appears to be genetically determined, with peak sensitivity to exposure occurring in children between the ages of 8 – 14 years. Urushiols and related phenolic lipids are found in other members of the Anacardiaceae. Locally this includes the native poisonwood tree (Metopium toxiferum) which contains highly allergenic alkenyl catechols similar to those found in Toxicodendron spp. This is a hazardous tree that is best limited to serious native plant collectors. Two other related plants of local interest are mango (Mangifera indica) and Brazilian pepper (Schinus terebinthifolius) which contain less allergenic alkenyl resorcinols and alkenyl phenols respectively. Brazilian pepper is one of the more common causes of plant induced dermatitis in Miami-Dade; allergens are concentrated within the bark, berries and new leaves. In mango allergenic alkenyl resorcinols (collectively termed mangol) are found in sap, but more significantly also in the skin of the fruit (trace amounts in flesh). The allergens in all of these members of the Anacardiaceae cross react with one another to varying degrees. For instance, there is good evidence that persons who has been sensitized by prior exposed to poison ivy are also likely to react to the allergens in mango skin. It is believed that those raised in mango growing areas who have consumed mango regularly from an early age develop a tolerance to mango induced allergic dermatitis. There is however no evidence of cross reactivity of the phenolic lipids found in philodendrons (see above) with extracts obtained from Toxicodendron spp. (treating dermatitis). Another fruit tree member of the Anacardiaceae sometimes seen in Miami-Dade is the cashew tree Anacardium occidentale). Great care needs to be exercised in handling the nut. In the interstices of the double-walled shell is an oily liquid containing several highly allergenic phenolic lipids especially anacardic acid as well as cardanol which also acts as vesicant (i.e., causes both an immediate and delayed (immunological response) and and vesicant, anacardic acid, which is structurally related to the alkenyl catechols (urushiols). Within the Asteraceae (sunflower family) delayed contact dermatitis is far less common; more familiar is the immune response elicited in response to the protein antigens of pollen, commonly known as hay fever. Apart from workers who commonly handle plants (e.g., nurseries and florists), it is most often middle age men who are most prone to develop delayed contact dermatitis to members of the Asteraceae. This involves repeated exposure to low molecular weight components, notably sesquiterpene lactones, found in leaves and stems. Many of these compounds are relatively benign (taste bitter to ward-off herbivores), and some have important medicinal properties, e.g., artemisinin from Chinese wormwood an anti-malarial. Only sesquiterpene lactones with a particular chemical configuration are allergenic, (i.e., function as haptens, and chemically bond with proteins so as to make them appear foreign). The landscape /house plants most often found responsible for dermatitis are chrysanthemums (crosses involving Dendranthema grandiflorum). There are other ornamental species to which susceptible individuals can become sensitized including Tagetes spp. (marigolds), Helianthus spp. (sunflowers), Tithonia diversifolia (Mexican sunflower), Pseudogynoxys chenopodioides (syn. Senecio confusus Mexican flame vine) and Gamelopsis chrysanthemoides (African daisy bush). Delayed contact dermatitis due to lettuce (Latuca sativa) has been reported, more often seen in food handlers. The Asteraceae contains familiar highly allergenic weeds such as ragweed (Ambrosia artemisiifolia) that, in addition to being important causes of hay fever, are linked to delayed contact dermatitis. Parthenium hysterophorus (parthenium weed) is a common weed locally in the Redland farming district. In hot dry climates (as occur in India and Australia) it has become a serious health problem and is responsible for widespread airborne dermatitis due to contact with dried wind-blown plant parts. Plants in the Araliaceae contain various polyacetylenes, especially falcarinol, which can cause irritant dermatitis and less often sensitize susceptible individuals to a delayed contact dermatitis. Most reports concern common ivy; however of more potential local relevance Schefflera arboricola (dwarf schefflera) also contains falcarinol and has been linked to delayed contact dermatitis. In Miami-Dade cultivars of this shrub (e.g., ‘Trinette’) are grown commercially and widely used in area landscapes. Symptoms develop following a history of frequent contact with cut stems or bruised leaves (during pruning or taking cuttings) when exposure to sap is more likely. Irritant dermatitis has also been reported after contact with Polyscias spp. (aralias) all parts of which contain saponins, plus polyacetylenes in at least one species, Polyscias fruticosa (ming aralia). For mild skin irritation washing with warm water and mild soap followed by use of hydrocortisone cream should produce some relief. For an extreme rash especially if accompanied by blisters seek advice from a health professional. I have been in awe of nature since I could crawl and I think I may have been born with a garden spade in my hand in lieu of a silver spoon. I have been gardening my entire life. When it comes to landscaping I grow everything cacti to aquatic edge plants, but always remembering the FYN mantra right plant in the right place. However until last year I had very few orchids in my garden collection. This is an opportunity for staff of the Miami-Dade Extension Office to provide a personal view of a plant they love (or hate!), from ornamentals to fruits and vegetables, South Florida natives to exotics. On this occasion Barbara McAdam of Florida Yards and Neighborhoods describes her late but passionate affair with orchids I once quipped that I was saving orchids for my old age, thinking them fussy and difficult to care for, and therefore requiring lot more time than I can afford to devote at present. Perhaps their sheer beauty when in bloom intimidated me. Surely achieving such perfect and intricate flowers required constant attention. Often when visiting friends who grew orchids I would see healthy green plants but few flowers. I seriously thought that it took forever for orchids to bloom, at least several years. I am not that patient! Over the past year a multitude of different orchids have found their way into my life, both here at the Miami-Dade Extension Office and a t home. I began to learn what it takes to keep the beautiful orchid you might receive as a gift, healthy and thriving and have it bloom again and again in your care. It bears repeating but Florida Yards & Neighborhoods Principle # 1, Right Plant, Right Place is again the key to success with orchids as it is for any plant you may wish to grow. I took the time to learn the names of the orchids, what niche they occupied in their native surroundings, and sort advice from both staff at the Miami-Dade Extension and local nationally respected growers. I credit my beginners luck to paying attention to watering needs being careful not to overwater! And locating the orchids where they can receive the sunlight they prefer. Since orchids are highly mobile being planted in pots and hangers etc. they can be positioned for seasonal sunlight. They do grow slower during a South.Florida winter and therefore require less water – over watering at this time can lead to several physiological disorders that mimic diseases.. Orchids are excellent choice to focus on understanding the watering needs of plants, and they thrive on water from my rain barrel. The Miami-Dade Extension Office was fortunate to receive a gift of orchids from Pine Ridge Orchids. Included was the one of the ‘swan orchids’ (Cynoches spp.) shown above at left. A collection of Phalenopsis were donated last August by a local wholesale orchid grower for the ribbon cutting ceremony celebrating the opening of the South Miami Dade Tropical Agriculture Vistors Center here at the Extension Office. These have bloomed again after a brief rest in our shadehouse as can be seen in the photo at right - what a perfect Valentines gift nesteled in a red wicker basket! The shady side of the 4-H/FYN Butterfly Garden provides an excellent location to showcase our donated orchid collection as plants come into bloom. Here the orchids are hanging from a scupted trunk of guava. Want to learn more? Redland/Homestead is truly an orchid collector’s paradise: The East Everglades Orchid Society meets here at the Miami-Dade Extension Office every 4th Tuesday of the month. The Redland International Orchid Show is scheduled for May 15, 16, & 17th at the beautiful Fruit & Spice Park (worth a visit in its own right), and there are several orchid societies and clubs in Miami Dade County including South Florida Orchid Society, North Dade Orchid Club and Orchid Society of Coral Gables . One of the most frustrating aspects of growing fruit trees is discovering that your favorite fruit is full of “worms” or otherwise damaged to the point that it’s inedible. Once damaged, the only option is to remove and dispose of all the infested fruit (both on the ground and still attached to the tree). Prevention is key, but how! Certainly not by using pesticides, which are largely ineffective. One of the most effective ways known to prevent insects from damaging fruit is exclusion using, of all things, paper lunch bags or even panty hose. This is based on methods that have been in used in China and Japan for centuries as a means of protecting tree crops from insect pests. There are several different insect pests that affect fruit trees in Miami-Dade. Guava and loquat are commonly infested with Caribbean fruit flies, papaya with papaya fruit flies, and annonas (sugar apple, custard apple, sour sop, and sweet sop) with a seed boring wasp. These insects look for unripe fruit as host for their progeny. The female has a tube-like appendage called an ovipositor Adult fruit flies are about ½” long. The female appears to be “stinging” the fruit when she’s laying her eggs. A paper lunch bag, laundry wash bag and nylon stocking used to protect fruit from pests. used to pierce the skin of young fruit to lay her eggs. Since the immature insects are inside the fruit that’s why it’s hard to tell if it’s infested. As soon as fruit sets (the flower petals have fallen and the fruit is becoming visible), it will need to be protected. Envelop each fruit in a paper lunch bag or even panty hose (knee high stockings). Commercial growers also bag vulnerable fruit crops – bags designed for the purpose are available. Avoid using plastic bags since moisture will build up which can cause your fruit to rot. If you are using paper bags or nylon stockings, use a twist tie, string or masking tape to close the neck of the bag or stockings around the branch. The bag or hose can stay on the fruit until it approaches mature size. At that point, the protectant can be removed. A papaya fruit fly laying eggs; the white If you are using paper bags or nylon stockings, use a twist substance is the latex-like sap from the fruit. tie, string or masking tape to close the neck of the bag or stockings around the branch. The bag or hose can stay on the fruit until the fruit are about mature size. At that point, the protectant can be removed. To protect papaya from the papaya fruit fly, try using a laundry wash bag. Choose bags that have a fairly tight weave so that the fly can’t get her ovipositor through. I have found laundry wash bags at grocery stores, bedding supply stores, and discount stores like Big Lots. Although not as easy to do, you could use paper grocery bags or even newspaper to envelop each papaya fruit. If you use newspapers to wrap each fruit, you’ll need to seal open seams with masking tape. For clusters of fruit, such as loquat, use a large paper bag or use laundry wash bags to encase multiple fruits. Have you ever wondered why your annona fruit became mummified? Well, it was infested with a small wasp called the annona Using paper grocery bags and newspaper to protect papaya fruit seed boring wasp. This insect can’t sting you but can ruin your annona crop. Once the immature wasp has finished developing inside the seeds, the adult eats its way out of the fruit and you will see a small hole where it emerged. Because of this injury, fruit rotting fungi infect the fruit which will cause the fruit to turn black and dry. If you weren’t able to protect your fruit in time, as soon as you see annona fruits with holes, remove them and dispose in the garbage. Information from the Univesity of Florida-IFAS is available on most common fruit infesting insects: papaya fruit fly; Caribbean fruit fly and Annona seed borer wasp . The above information should help you enjoy a bountiful and insect Mummified sugar apple protein-free harvest! Butterfly gardening can have a therapeutic effect on those who enjoy nature. Therapy gardens are being established around the country to offer a place for renewal and contemplation for those suffering from illness. In South Florida, places such as Butterfly World in Palm Beach County or Fairchild’s Wings of the Tropic’s exhibit or the Key West Nature Conservancy, give visitors a sense of being one with nature. Adding a selection of butterfly plants to a private garden, allows homeowners to enjoy this beauty more frequently and with little maintenance. While observing a caterpillar, finding a chrysalis on a stem or seeing a new species adds interest and satisfaction; digging, weeding and pruning can also provide relaxation to the home gardener. There is another aspect of butterfly gardening that brings pleasure; the fragrances. This article will focus on five lesser known butterfly plants that will bring a new dimension to your garden by adding a variety of aromas. Spurred Butterfly Pea-(Centrosema virginianum) This native twining vine is a host plant for longtailed skipper and cloudy-wing butterflies. The sweet lavender colored flower blooms in the rainy season. This plant thrives in moist sandy soils .Grows to 6 feet or more in length. The fruit is a flattened pod. Spurred butterfly pea Butterfly Ginger-(Hedychium Coronarium) Butterfly gingers are known for their showy floral displays that bloom intermittently in South Florida. Flowers are available in white, pink, orange, and red and appear on flower stalks that rise above the foliage. It is best to cut back old stalks when they die to encourage new growth. This plant is a perennial and will stay green all year in South Florida provided it is irrigated regularly during dry season. They typically grow 4 to 8 feet tall and 2 to 4 feet wide. Once established, these Florida-Friendly plants need little care aside from watering. Bolivian Sunflower-(Tithonia diversifolia) Tithonia, also known as Mexican Sunflower, can grow as high as 20 feet in the South Florida garden. The flower is a bright orange-yellow and has a large brown center full of seeds for birds to enjoy. The bloom has a distinctive honey fragrance that follows the breeze. It can be cut back rigorously to 3-4 feet and will reestablish itself. It attracts birds, butterflies and bees. However, this plant can be intrusive in South Florida, so make sure you keep it Bolivian sunflower under control by trimming as needed. Milky Way Tree, Lecheso -(Stemmadenia litoralis) Milky Way Tree is one of the most beautiful and fragrant tropical species. It is a small tree with a multi-layered canopy, dark green, oval shiny leaves, about 6 inches long. Lecheso produces white, musky scented flowers, throughout most of the year. The flower looks like a small white pinwheel. When in full bloom, perfume fills the area with a soft fragrance. A massive abundance of flowers cover the branches, white against the glossy leaves. The small fruit are pods, golden in color and about 4 inches long. Related to pinwheel jasmine (both in the pocynaceae). Lechoso - note forked branching (inset shows flower) Sweet Almond-(Aloysia virgata) A butterfly nectar plant that attracts monarchs, sweet almond may have the most pleasant fragrance of all. This leggy plant likes lots of sun and unless kept very short, may need a trellis on which to climb. Sweet Almond a waft of fresh vanilla almond perfume to anyone in proximity. The flowers are a delicate white cluster in the shape of a cone and typically bloom on new growth. Please be aware the pollen may allergies. The plants shown above are meant to supplement your garden and should be planted with native host plants, such as milkweed, coontie, wild lime, firebush and wild coffee. Recommended milkweeds for South Florida are butterfly milkweed (Asclepias tuberosa); swamp milkweed (Asclepias incarnata); pinewoods milkweed (Asclepias humistrata); longleaf milkweed (Asclepias longifolia); and aquatic milkweed (Asclepias perennis). Further information related to butterfly gardening is available using the following Sweet almond links: larval and host plants for butterfly gardening in Florida; challenges facing monarch butterflies if Florida; Neighborhood butteflyscaping in Florida and an introduction to therapy horticulture. The Myrtaceaea are found in various tropical and subtropical areas of the world especially tropical Americas (neotropics) and Australia. In the Americas they extend A selection of into southern/central Florida where Myrcianthes fragrans myrtaceous shrubs (Simpson’s stopper) occurs as the furthest north native member of the family. and small trees Most of the colorful myrtaceous plants found in local landscapes are native to Australia and include Callistemon spp. (bottlebrush) and to a lesser extent certain eucalyptids. Those from the Americas that feature in Miami-Dade landscapes are less colorful but have neat, attractive and usually aromatic foliage, white flowers and often colorful peeling bark. Among this latter group are various species native to Miami-Dade, including, in addition to Simpson’s stopper, spicewood (Calyptranthese pallens) and several other stoppers (Eugenia sp). In addition are non-native species with guava and Surinam cherry most frequently encountered, the former principally as a fruit tree the latter having been popular as hedge material (though the fruit is edible). While both of these plants have been judged to be invasive, there are other non-native myrtaceous plants that provide both edible fruit and landscape appeal, and are not known to be invasive. The fruit of several myrtaceous genera have attracted attention since they contain elevated levels of polyphenols, potent antioxidants (help prevent cell damage). Of particular interest are Syzyigium spp. (e.g., mountain apple S. Mountain apple a highly ornamental fruit tree in blossom malaccensis) of Indo-Malayasian and Auastalian origins showing exserted, pollen-tipped, scarlet stamens and Eugenia, Myrciaria and Pimenta from the neotropics. It is this latter group that is the focus of the present article, with Brazil being an especially rich source of species with both palatable fruit and utility as attractive landscape shrubs and small trees. Most frequently seen is the jaboticaba (Myricaria cauliflora), a very slow growing, shrubby tree from Brazil which locally is rarely more than 15’. Jaboticabas have smooth, flaking, reddish brown bark, branch frequently from close to the ground, eventually developing a vase like shape. New leaves are pale red becoming dark green to no more than 4”, but the most outstanding feature is the cauliflorous habit of flowering. Several times a year, fluffy white flowers are borne directly on the multiple trunks and branches. From a distance the tree appears to be covered with patches of fresh snow. The flowers are soon followed by reddish purple to almost black grape like fruit with a thick skin and pleasantly sweet to sub-acid pulp. The false jaboticaba or blue grape Myrciaria vexator is especially ornamental with striking peeling bark and blue fruit, which is of excellent quality (some may find the skins tough). Jaboticabas should be grown with full sun exposure in moist enriched, but free-draining soil – they will not survive flooding. They have very limited tolerance of drought or salt. On Miami-Dade’s limestone soils jaboticabas usually develop nutritional deficiencies, which should be corrected using appropriate soil drenches (iron) and nutritional sprays (manganese, zinc etc.). Periodic applications of fertilizer are necessary, Myrciaria vexator - peeling bark about 2 lb every 3 months when fully grown. Do not allow the soil to (top); blue berries (bottom) become dry, apply water on a regular basis as needed. An organic mulch helps to conserve soil moisture as well as enriching the soil. Vegetative methods of propagation are difficult. Fortunately seeds are polyembryonic, so seed grown jaboticabas are very similar to the parent tree. One slight caveat concerning jaboticabas: you will need patience since it will take about 8 years before you can expect the tree to be fruitful; there is now one report of a selection that is claimed to commence setting fruit after 3 years. The grumichama Eugenia brasiliensis is another slow growing small tree in the Myrtaceae from Brazil. It develops a less shrubby appearance than the jaboticaba, growing into a very attractive narrow upright tree to about 20’. The leaves are larger and thicker (up to 5 x 2½”) than those of the jaboticaba, with recurved edges. During April the tree suddenly bursts into a showy mass of 1” white flowers that form in the leaf axils. This occurs in response to rainfall, and is followed about 4-6 weeks later by a crop of fruit similar in appearance to jaboticaba. However the flavor is less grapelike and closer to that of a cherry – there may be a slightly Grumichama blooming on Miami-Dade resinous taste, though usually not objectionable. In order to limestone obtain good fruit set the tree needs to be in sun, and most importantly irrigated to ensure that the soil remains moist once it has flowered. A second flowering may occur if flowers drop but it is not as heavy. Mulching is especially beneficial to protect the shallow roots from drying out. The grumichama like the jaboticaba is also prone to nutritional deficiencies on local limestone, and for this reason has a reputation as being difficult to grow in Miami-Dade. Trees will look attractive and set heavy crops if soil moisture is maintained and the fertilizer recommendations for jaboticaba are followed. If you can grow gardenias, you are on your way to succeeding with both of these trees. Several Eugenia species from Brazil esteemed for the fruit they produce also enhance the landscape with their neat foliage attractive bark and white flowers. Below are some is a selection of some of those more familiar locally: Cherry of the Rio Grande Eugenia aggregata is slow growing to 15’ with thin peeling bark and very attractive white flowers. After flowering in Late April the deep purple sub-acid fruit (shown at right) is ready for harvesting by June. It is cold hardier than the other eugenias listed below, and can with stand brief exposures to 20⁰F. Pitomba Eugenia luschnathiana is a very slow growing bushy tree to about 15’ with glossy lanceolate leaves. After flowering, which commences in April, yellow to orange 1” obovoid fruits are ready for harvesting late May-June and are sweet to sub-acid somewhat resembling an apricot. On Miami-Dade’s limestone soils pitomba is not as prone to iron deficiency as the other trees reviewed. Brazilian pear Eugenia klotzshiana A medium shrub to about 6’ with densely hairy, oblong to lanceolate, leathery leaves (new stems also hairy). White flowers are followed by up to 4”pyriform fruits with downy yellow skin and highly aromatic, acidic, juicy flesh (used to flavor ice cream, jams and baked goods). Brazilian pear requires a free draining sandy acid (pH 4.0 – 5.5) soil; in Miami-Dade where soil pH> 7.0 it is advisable to grow in a large container (all of these eugenias are amenable to container culture). Arazá Eugenia stipitata is a shrub or small tree which grows up to 2.5 m. with a fair degree of branching from the base. The leaves are simple, opposite, elliptical to slightly oval and measure 6 to 18 x 3.5 to 9.5 cm. The flowers are white in axillary racemes, usually with two to five flowers per inflorescence. The fruit is a subspherical berry, up to 4” in diameter with thin velvety yellow skin, the pulp yellow, fragrant, and acidic with a few 1” oblong seeds. The subspecies stipitata has fewer stamens and an arboreal habit, whereas the subspecies Arazá fruits grown in Miami-Dade (Redlands) sororia has a shrub habit and has more stamens. Arazá has been enjoying some limited popularity in N. America as a health drink. Eugenia pyriformis Uvalha (or uvaia, shown at right) is from the southernmost Brazilian states and is also well suited to Miami-Dade, not as intolerant of local high pH soils and far more tolerant of drought compared to grumichama or jaboticaba. Like these two trees, uvalha is both slow growing and intolerant of salt or flooding. It prefers a light, free- draining soil of moderate fertility, and a full-sun location. The fruit is a 1” pear–shaped berry with yellow to orange skin and soft, aromatic, sweet/tart pulp. These are sometimes consumed out of hand, but more often the juice is extracted for use in drinks and jellies. Cultivars producing acid (azeda) or sweet (doce) fruit are grown in Florida by tropical fruit enthusiasts. The juice is reportedly similar to that from araza. Finally the allspice tree (Pimenta dioica), far more familiar locally and definitely a landscape asset but one where backyard growers will find difficulty in setting fruit. Although flowers appear perfect (male and female parts) some trees are functionally male, producing abundant pollen but rarely any fruit. Other trees have flowers with non-viable pollen and are functionally female (unless pollinated by ‘male’ trees they produce few if any berries). Termed incipient or cryptic dioecy, this means in practice that in order to set fruit both types of tree are required. Irrespective of these constraints on fruit production, allspice is a very attractive, slow growing tree, well adapted to Miami-Dade’s limestone-based soils. A recent UF-EDIS publication on Africanized bees warns about the unnecessary fear of bees encouraged by the sensationalized media reporting. Resources are provided where the public can be become more informed and so act in a more rational manner if confronted with a bee colony on their property. One misconception is that it is possible to identify Africanized bees by their appearance. Only genetic analysis in the laboratory can definitively confirm a bee is indeed ‘Africanized’ – in the field, aggressive behavior by more than a few bees is a strong indication that the colony is at least partly ‘Africanized’. Palm fronds that are still green collapse or are found on the ground with the proximal end of the petiole (the 'stem' that attaches the frond to the palm trunk) appearing to have been chewed. This is a not an uncommon occurrence at this time of year (dry season) and is usually due to roof rats attempting to find a moisture source. For suggestions on controlling roof rats use the linked publication. Mothballs have been recommended in some quarters for controlling nuisance wildlife from snakes to raccoons. Since mothballs are regulated as a pesticide and not labeled for this purpose such use is illegal; other products are available that are labeled for deterring nuisance wildlife. In some cases it may be necessary to resort to trapping but be aware of the strict rules on relocating trapped animals and disposing of them if kill traps are used. Another alternative is to hire a wild life trapper. As winter morphs into spring, temperatures rise and weeds can become an increasing problem in local landscape maintenance. The use of mulch and hand removal of weeds can often suffice but it may become necessary, especially for a large or previously neglected property, to use herbicides. It then becomes very important to choose a product appropriate for the situation. Some herbicides can be sprayed over the top of existing landscape installations to control invading weeds, while others are for use around landscape plants and contact with them must be avoided. In the later instance wicking applicators may be a safer choice where drift of herbicide is a concern. A rope/wicking type herbicide applicator - there are many other types available As May approaches review your options for the vegetable garden during summer. You could cover it with clear plastic for solarizing then later work in some compost ready for planting next fall . Another option is to grow a At this time cover plant for use as a green manure – this may also help to reduce the of year….. number of pathogenic soil nematodes. If you decide to plant a crop, the following vegetables are suitable for a Miami-Dade summer garden: Some timely *Calabaza (Cuban pumpkin), *chayote, eggplant (can rapidly become bitter information for Miami-Dade if allowed to fully ripen), *New Zealand spinach, *okra (plant as early as landscapes late February), southern peas (also *pigeon peas), sweet potatoes (*boniato), *lemon grass and rosemary. If an asterisk* is present find information in ‘Manual of Minor Vegetables’. At this time of year it is normal for avocado leaves to yellow and drop, sometimes rapidly enough that the trees are almost bare. There is no need to be alarmed as it is all part of the process of leaf renewal and is followed almost immediately by bloom production. On occasion a tree can be practically leafless and covered with blooms, though new leaves will quickly emerge. This is a good time to apply a complete granular fertilizer . Don’t be surprised further if much of the fruit that sets soon drops – this again is normal; there may also be a later drop of fruit sometime in May/early June. Do not allow turf to become drought stressed as this makes it more susceptible to take-allroot once rainy season commences, a disease that is difficult to control once symptoms develop. Last summer into fall this proved to be a common problem in Miami-Dade. Applying one of the recommended fungicides 2-3 weeks before the start of rainy season and monthly thereafter can help prevent the disease from becoming established, and should be considered if the disease has been a problem previously. If you are planning changes to your landscape be careful of freebies that sprout up in the yard. This potted specimen was grown by a local resident from some seeds that dropped from a large tree, but is definitely not something you should be considering planting out in your yard. It’s a bischofia (Bischofia javanica) which makes a large, fast growing tree for shade. On the debit side it is messy and invasive, added to which propagation, Bischofia javanica seedling planting or selling the tree is illegal in Miami-Dade. If you find something growing in your yard and are considering wheter it’s worth allowing it to remain, first have the plant identified or at least transfer it to a container until it can be identified. As a rule of thumb, in most instances trees and shrubs that volunteer are not desirable aditions to the landscape.. Be careful when choosing herbicides to control weeds in turf; first read the label thoroughly to be certain it is safe to use on your type of grass otherwise you could severely damage or kill your lawn. Note that applying herbicides to turf that is drought stresed or when temperatures exceed 85⁰F increases the risk of damage. Two low growing, spreading weeds that can become problems when turf is maintained overly moist are tropical or West Indian chickweed (Drymaria cordata) and Florida pellitory (Parietaria floridana). They may appear superficially similar but can be easily distinguished; the leaves of tropical chickweed are kidney to heart shaped, opposite and almost sessile compared to Florida pellitory with alternate, egg-shaped leaves on long stalks. Another difference that helps identify Florida pellitory are the almost translucent stems (another common name for the weed is clearweed). In addition Florida pellitory is more ikely where there is shade and during the cooler months of the year. If either of these weeds are a particular problem carefully check the herbicide label to see if they are listed. If your landscape plans involve using plants native to South Florida, in particular Miami-Dade pine rockland, then consult a recent Miami-Dade Extension publication that presents information on understory and groundcover plants. This is a useful resource if you looking for native plants Tropical chickweed (top) and Florida pellitory (bottom) that are drought tolerant and suited to full sun exposure. Legal issues may be somewhat outside the purview of this newsletter but many are confused about legal rights regarding overhanging branches and roots from neighboring trees. A recent UF-Extension publication that addresses these issues should help to remove some of the confusion. The start of rainy season in mid-May is a good time to plant a palm; rainfall is more reliable and there’s time for the palm to become sufficiently established before the stress of winter. There are plenty of small palms suitable for the average size lot, and understory palms such as Chamaedoeas are useful where deep shade prevents the use of most other shrubs. If there’s need for a privacy screen and shade is a problem try a line of bamboo palms. Chamaedorea cataractarum – cat palm a trouble free palm ideal for shade and local limestone soils If you’re wondering how else Miami-Dade Extension helps county residents call or use the internet links to our office shown below – there’s assistance with food preparation, nutrition, health and managing family finances, plus an active 4H youth development program. Boaters, anglers and those who care for our marine environment will find information and activities within the local Sea Grant program. Send any general comments concerning Miami Green Bytes to the editor and for a specific article contact the author using the e-mail links provided below. Look for the summer issue of Miami Green Bytes during June 2015 The Miami-Dade County Extension Office, a division of Miami-Dade County Department of Regulatory and Economic Resources, is located at 18710 SW 288 Street, Homestead, FL 33030, and can be contacted at 305 2483311 or by e-mail: [email protected] . Web site: http://miami-dade.ifas.ufl.edu/ Contact persons for the articles in this issue are :Barabara McAdam (I’d like to tell all about … orchids); Adrian Hunsberger M..S. (Protecting fruit from damaging pests prior to harvesting); Jennifer Dewsnap-Shipley, Master Gardener (Five fragrant plants for your South Florida butterfly garden); and John McLaughlin Ph.D. (remainder) Photo Credits: Idioblast from Dieffenbachia (Dr. Gary Coté, Radford University VA); Epipremnum rhaphides 600x (Wikimedia); Parthenocisus quinquefolia (Wikimedia); Toxicodendron radicans (Wikimedia); Lime photodermatitis (CNN); Bagging papayas (Gardenweb forums); Spurred butterfly pea (Southern Weed Science Society); Flower of Stemmadenia litoralis (Forest & Kim Starr); Eugenia aggregata fruit (Top Tropicals); Myrciara vexator – fruit and tree bark (Top Tropicals); Azara fruit (Redland Rambles); Uvaia fruit (Polynesian Produce Stand); wicking herbicide applicator (Wordpress.com); West Indian chickweed (University of Georgia); Chamaedorea cataractarum (Mike Gray Palmpedia) and remainder Barbara McAdam, Adrian Hunsberger & John McLaughlin. The Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences (IFAS) is an Equal Employment Opportunity – Affirmative Action Employer authorized to provide research, educational information and other services only to individuals and institutions that function without regard to race, color, sex, age, handicap or national origin. U.S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE, COOPERATIVE EXTENSION SERVICE, UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA, IFAS, FLORIDA A. & M. UNIVERSITY COOPERATIVE EXTENSION PROGRAM AND BOARDS OF COUNTY COMMISSIONERS COOPERATING For sign language interpreters or materials in accessible format or other ADA Accommodations please call Donna Lowe at (305)248-3311 x 240 at least five days in advance.

© Copyright 2026