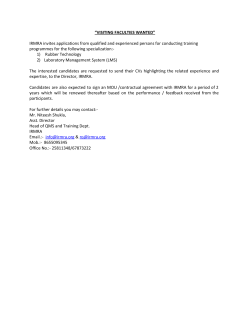

women`s leadership as a route to greater