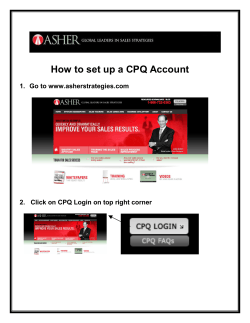

MRCT Return of Results Guidance Document - Multi