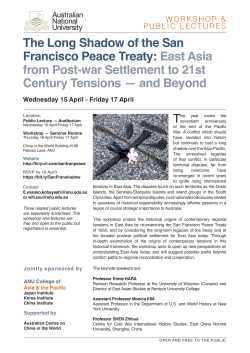

View PDF - Notre Dame Law Review