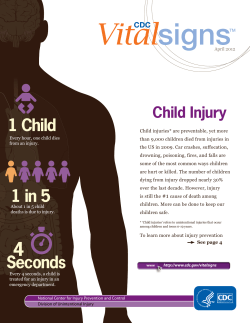

National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion