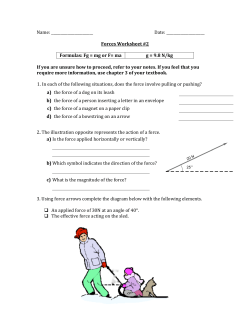

Selectivity of Television Media - Politics and Government| Illinois State