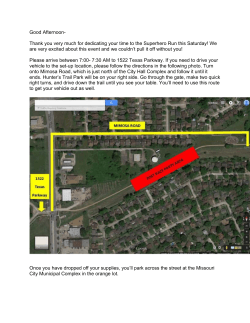

Rural Transport - PPCR