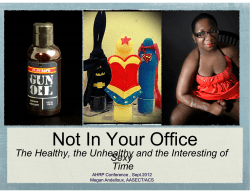

From top to bottom A sex-positive approach for